On Wednesday, December 6th, 2023, Education Policy Initiative Director Chelsea Coffin testified before the D.C. Council Committee of the Whole, at its public hearing on academic achievement in the District. Her testimony focuses on trends in academic achievement across grade bands integrated with chronic absenteeism rates. You can read her testimony below, or download a PDF copy.

Good morning, Chairman Mendelson and members of the Committee of the Whole. My name is Chelsea Coffin and I am the Director of the Education Policy Initiative at the D.C. Policy Center, an independent think tank focused on advancing policies for a growing and vibrant economy in D.C.

The pandemic-induced virtual learning in school years 2019-20 and 2020-21 lasted over a year, presenting profound challenges to D.C. students’ learning and wellbeing. Although students were back in classrooms, pandemic-related disruptions persisted throughout school year 2021-22. This made school year 2022-23, in some ways, the first normal year of school after COVID-19 began and a better point in time to take stock of what is needed in terms of academic recovery.

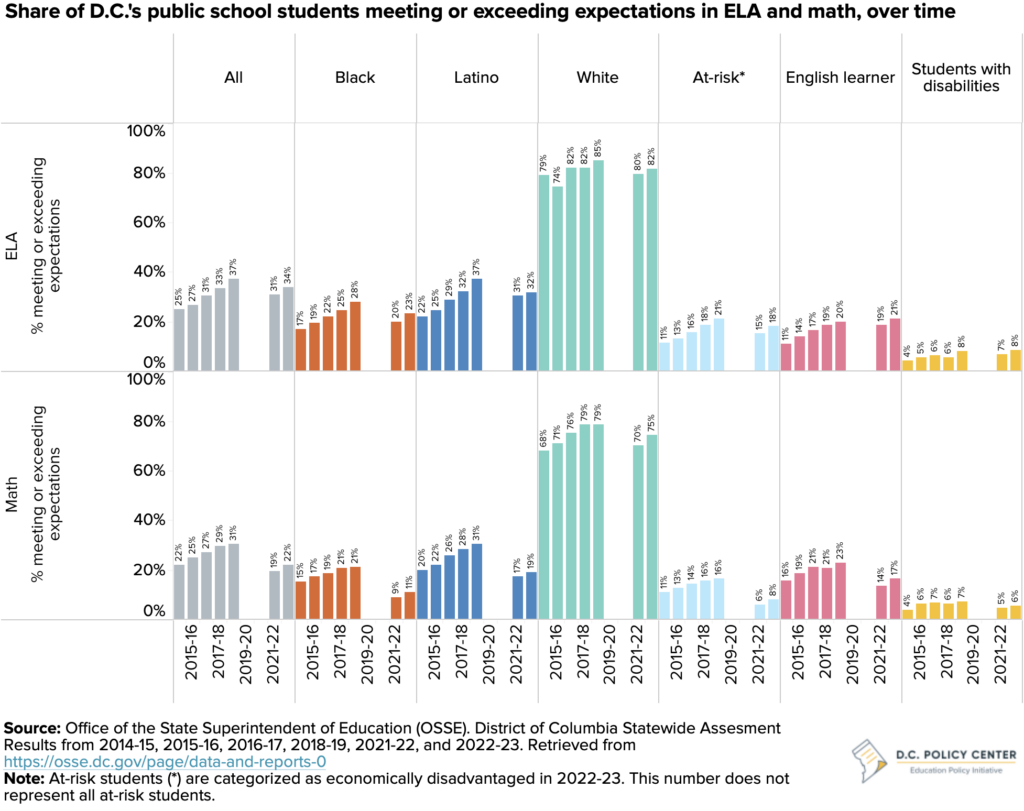

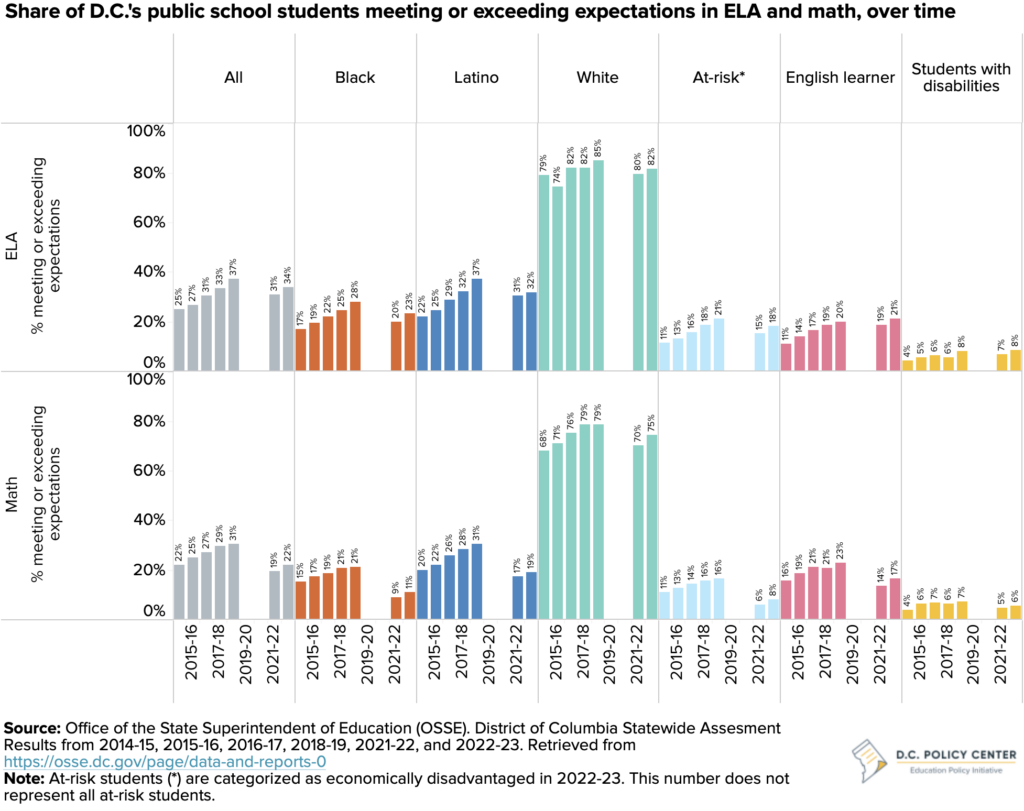

The results of the PARCC statewide assessment for school year 2022-23 show that recovery, in terms of learning, is off to a good start but it will be a long road. Overall, the share of students meeting or exceeding expectations increased by 3 percentage points in both English Language Arts (ELA) from 31 percent to 34 percent and math from 19 percent to 22 percent compared to school year 2021-22, the first year of statewide assessment since the pandemic started.1 These gains are on par with average annual pre-pandemic growth of 3 percentage points per year for ELA and 2 percentage points per year for math. Importantly, students in the largest race and ethnicity groups (Black, Latino, and white students) as well as special populations—including students who are designated as at-risk, students with disabilities, and English learners—experienced gains.2

These are substantial gains, but not enough to produce recovery.

The share of students meeting or exceeding expectations is lower than pre-pandemic school year 2018-19 in both ELA (by 3 percentage points) and math (by 9 percentage points). For math, the results in school year 2022-23 have returned to the levels of nine years ago. For ELA, results in school year 2022-23 are close to five years ago. These numbers underscore the magnitude of learning loss. They also highlight the critical importance of setting ambitious goals for achievement and rigorously tracking them in the years to come.

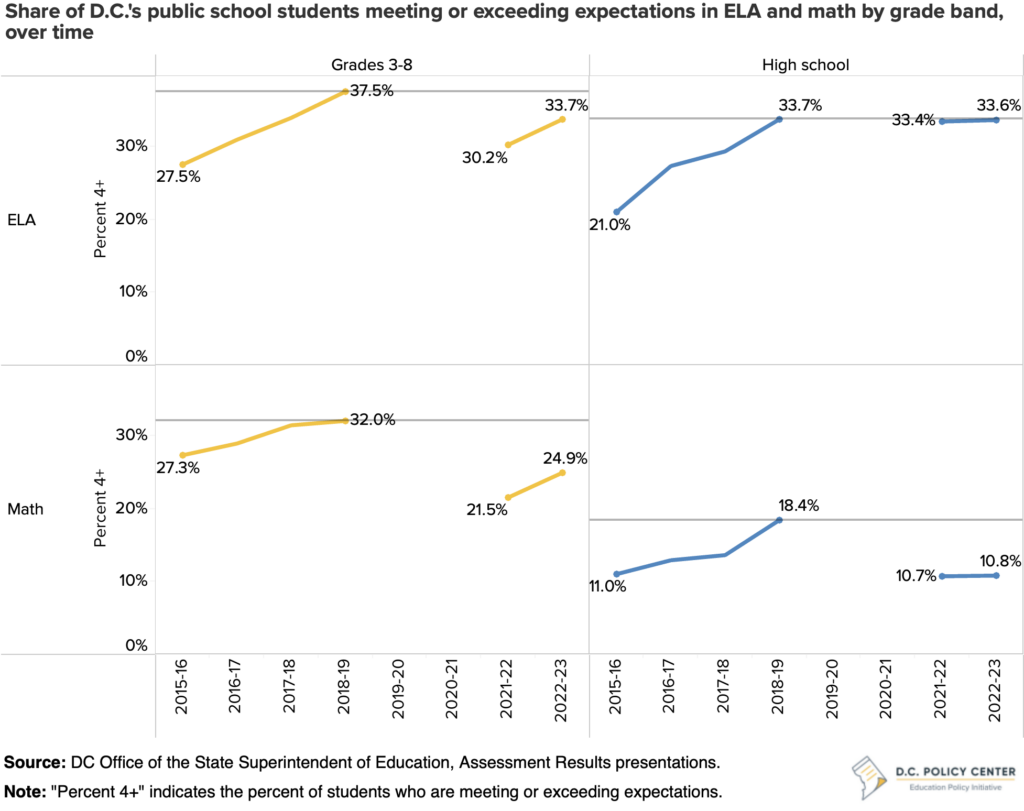

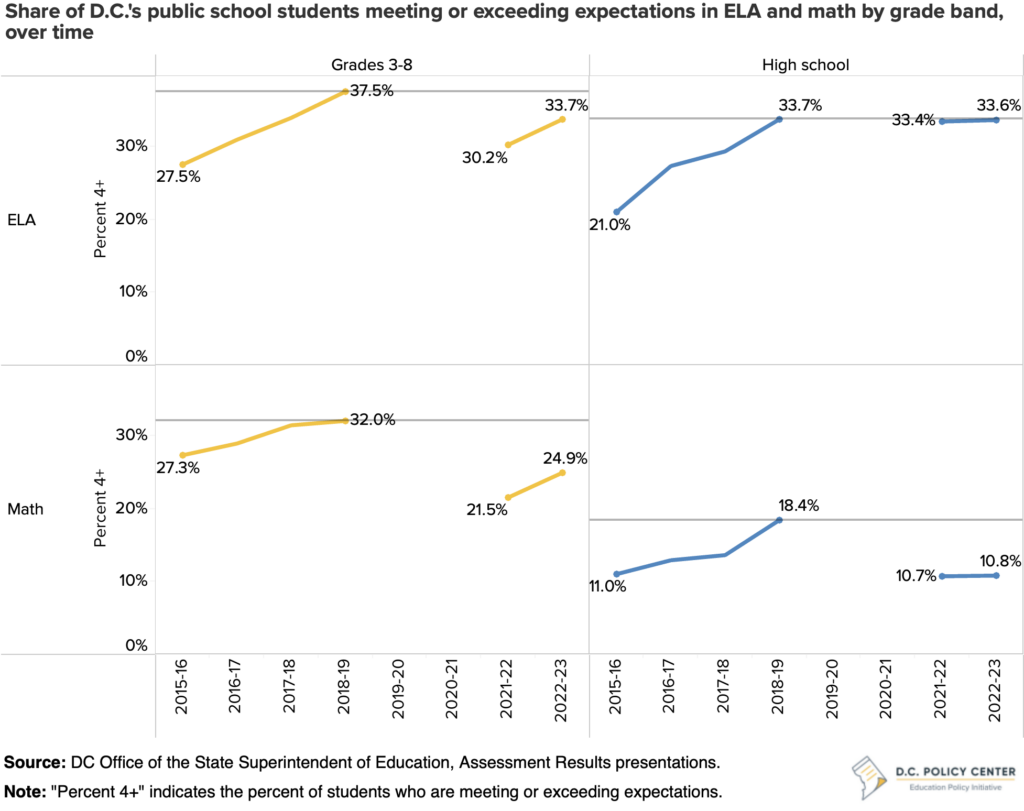

A deeper dive into these numbers show a stronger recovery for elementary and middle school students, and no growth for high school students.

Learning outcomes for elementary and middle school students (grades 3 to 8) improved by 3.5 percentage points in ELA, an annual rate consistent to pre-pandemic years. In math, learning outcomes for this same group increased by 3.4 percentage points, which is higher than annual increases pre-pandemic.3

Results for high school students, on the other hand, showed no growth in either subject during this recovery period.

For context, most of these high school students were in middle school when the pandemic began. For ELA, proficiency for high school students is comparable to school year 2018-19, with 33.6 percent of students meeting or exceeding expectations. But there has been little change from last year. For math, proficiency for high school students dipped back to school year 2015-16 levels, with 10.8 percent of students meeting or exceeding expectations (compared to 18.4 percent in school year 2018-19). Similarly, there was no gain in math for high school students between school years 2021-22 and 2022-23.

One factor influencing the lack of growth in achievement in high schools could be high levels of chronic absenteeism.

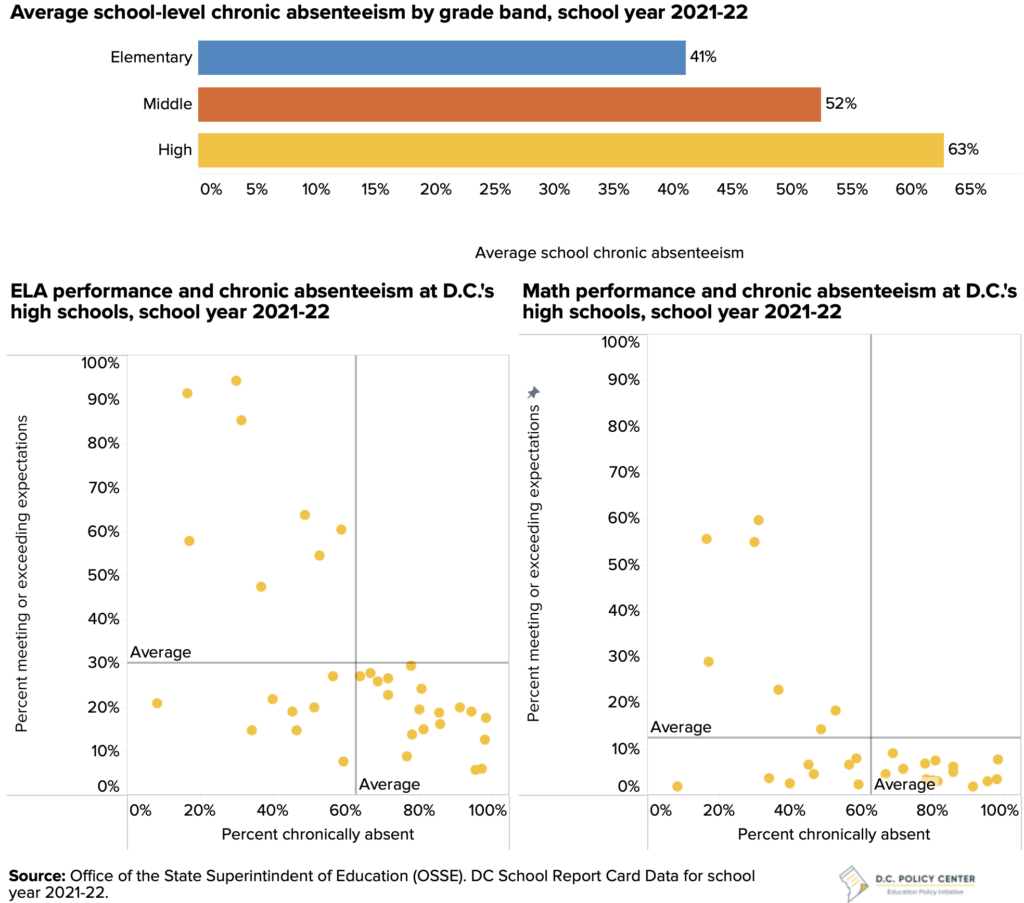

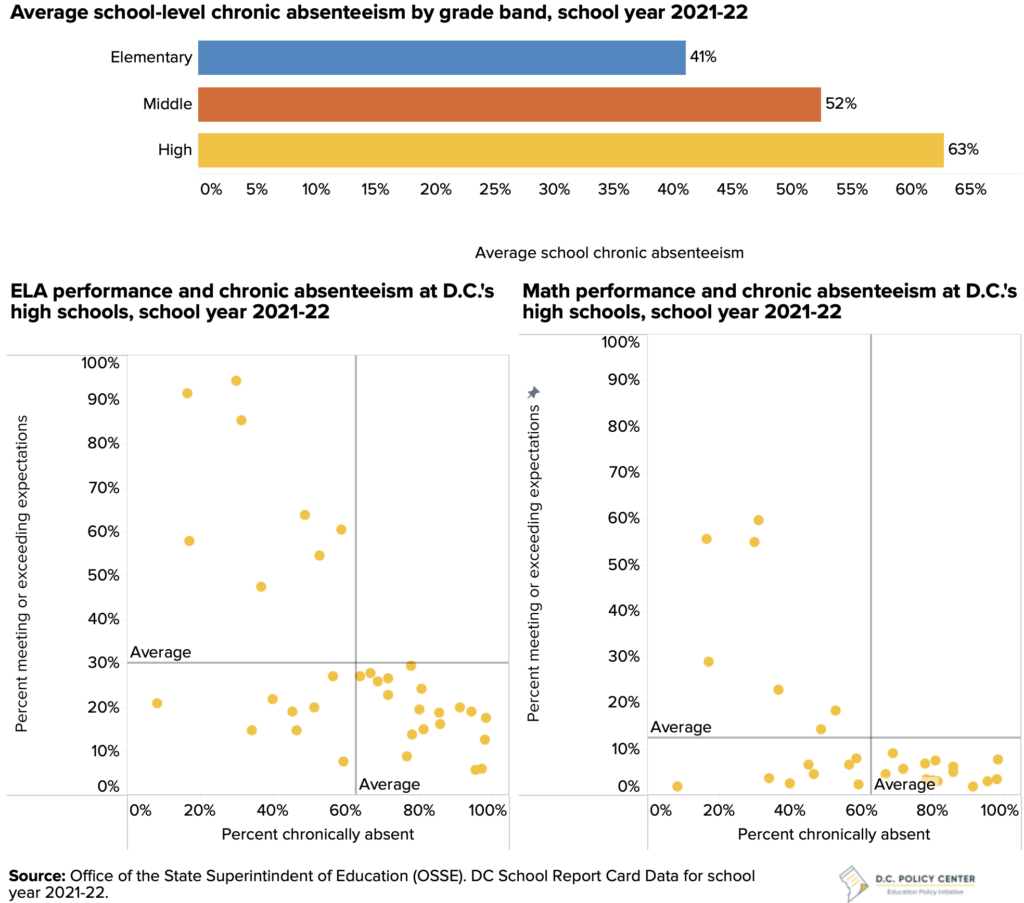

After the pandemic, chronic absenteeism rose to 48 percent in school year 2021-22 from an already-high 29 percent before the pandemic4 (chronic absenteeism improved but remained high in school year 2022-23, at 43 percent).5 Chronic absenteeism was especially acute in high schools, with the average high school having 63 percent of students chronically absent. At 6 high schools, 90 percent or more of students were chronically absent. Comparing chronic absenteeism at high schools to PARCC results, there are no high schools with above average absenteeism and above average achievement. Students must be present to learn, and reducing chronic absenteeism is a factor in improving academic achievement in upper grades.

While elementary and middle school students experienced higher gains compared to high school students, at this pace of recovery, it will still take years to catch up with where D.C. could have been without the impact of the pandemic.

If D.C. had continued to improve at the same rate as the four years before the pandemic, 38 percent of students would now have met or exceeded expectations in math. Instead, at the current rate of improvement, that’s now projected to occur five years later in school year 2026-27. Similarly, in ELA, if learning outcomes had continued to improve at pre-pandemic rates, a potential 51 percent of students would now have met or exceeded expectations—which is now expected seven years later in school year 2028-29.

To ground recovery investments, D.C. needs to set targets for academic outcomes, but this should be done in tandem with reducing chronic absenteeism.

Absenteeism undermines the significant investments the District has made into student academic achievement and wellbeing. This is a tough problem to solve, but it should be front-and-center in the District’s recovery efforts.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify, and I welcome any questions you may have.

Endnotes

- Coffin, C. 2023. “Chart of the week: New PARCC data show overall gain for DC students last year—but high school progress remained flat.” D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/parcc-data-gains/

- EmpowerK12. 2023. “2023 DC PARCC Results: A Step Forward, But How Big and Equitable?” EmpowerK12. Retrieved from https://www.empowerk12.org/blog/detailed-look-at-the-2023-dc-parcc-results-a-step-forward-but-how-big

- Coffin, C. 2023. “Chart of the week: New PARCC data show overall gain for DC students last year—but high school progress remained flat.” D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/parcc-data-gains

- Coffin, C. and Rubin, J. 2023. State of D.C. Schools, 2021-22: In-Person Learning, Measuring Outcomes, and Work on Recovery. D.C. Policy Center. Retrieved from https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/schools-21-22/

- District of Columbia Office of the State Superintendent (OSSE). 2023. District of Columbia Attendance Report, 2022-23 School Year. OSSE. Retrieved from https://osse.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/osse/publication/attachments/2022-23%20Attendance%20Report_FINAL.pdf