Recent research from a team headed by Stanford economist Raj Chetty made headlines last year when it outlined the stark divide in health outcomes between high- and low-income Americans. As the New York Times reports, the Health Inequality Project found that longevity has steadily increased across the nation for the richest Americans, but life expectancy for the poor is highly variable depending on where they live. In this measure, Washington, D.C. does not fare well: Among the 100 most populated counties, D.C. ranks 65th by average life expectancy for the poorest 20 percent of its residents.

While the Health Inequality Project’s study focuses at life expectancy disparities at the county level, the CDC’s and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s 500 cities project provides more color to the stark health divide between D.C.’s richest and poorest. Using this data to compare the District’s 32 highest income census tracts, which all make over $110,000 a year, with the 32 lowest income tracts, with annual income under $35,000, reveals striking disparities across behavior, health, and chronic conditions.

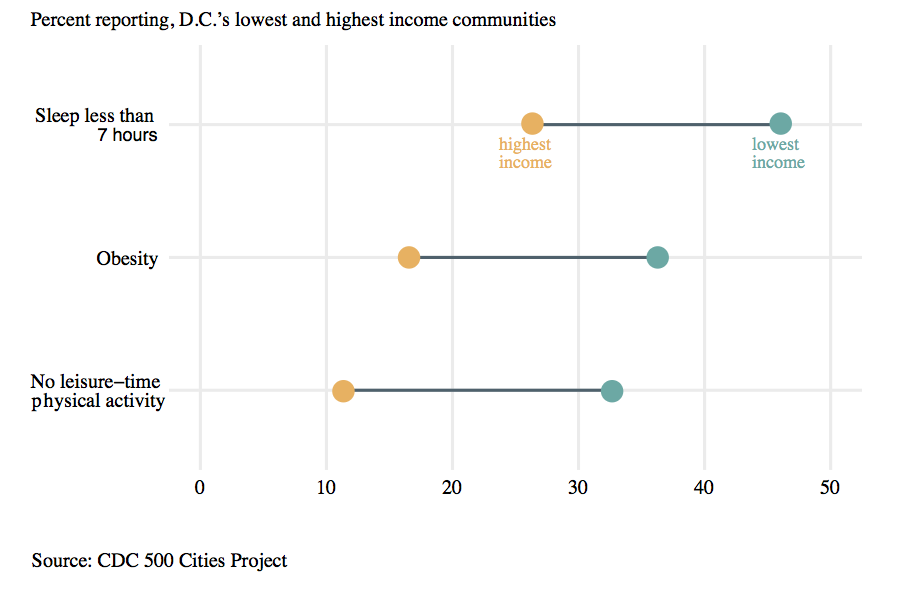

The wealth gap in healthy activities

Members of D.C.’s poorest communities were twice as likely to be obese, and report regularly receiving fewer than 7 hours of sleep. They were also three times as likely not to exercise. Higher rates of obesity, along with less sleep and exercise, are well-documented effects of longer commute times, fewer walkable areas, food deserts, crime, and stress associated with poverty. The one reported unhealthy activity wealthiest residents were more likely to partake in was binge drinking.

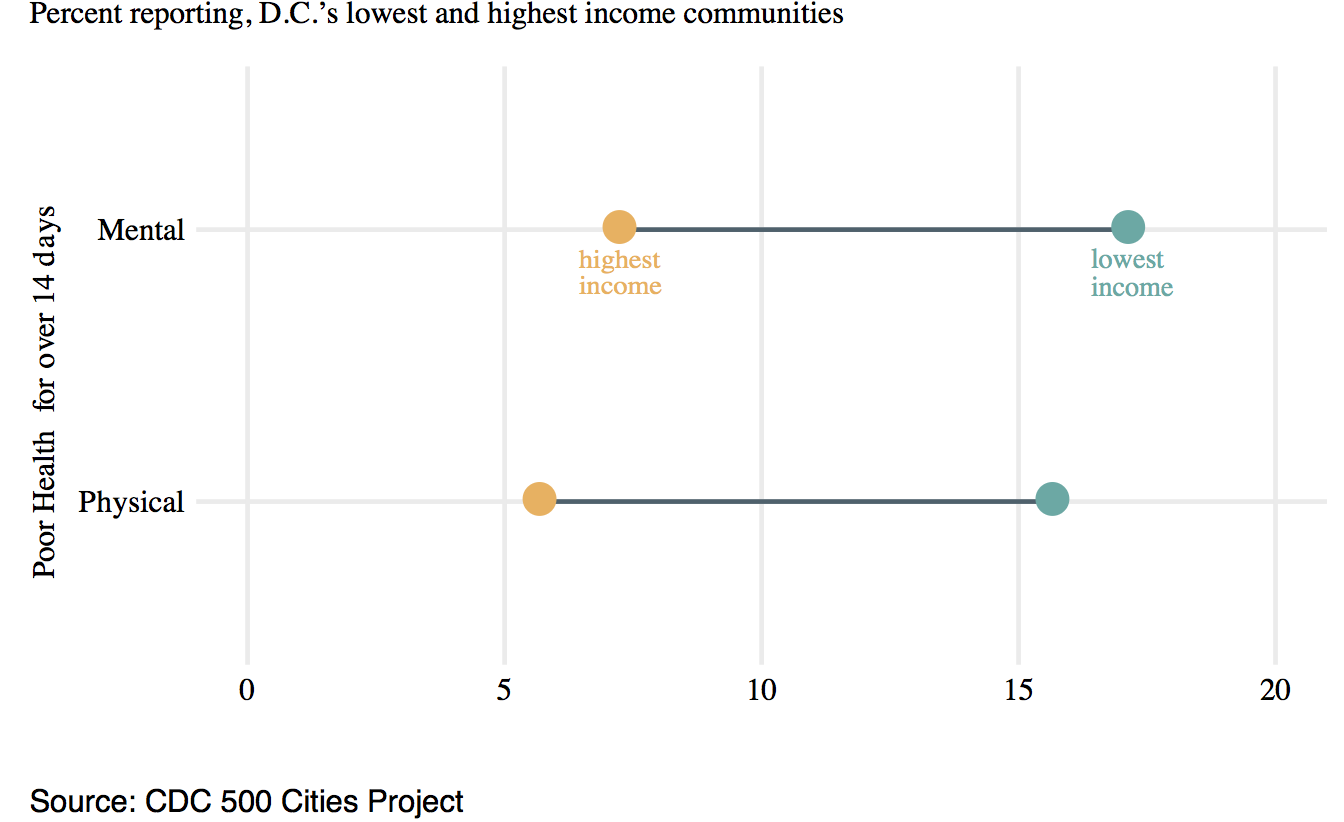

Those in D.C.’s poorest communities more consistently feel worse

Furthermore, residents of the lowest-income neighborhoods were more than twice as likely as those in the highest-income neighborhoods to report experiencing consistently poor mental health for over two weeks, and three times as likely to report consistently poor physical health. And when they don’t feel well, it’s also more difficult for low-income residents to receive treatment, as healthcare resources are less accessible in poorer communities. The data shows that while lower-income residents were slightly more likely to have a routine checkup in the past year than high-income residents, they were less likely to have standard health screenings, such as pap smears, colonoscopies, and cholesterol screening. Lower-income residents were nearly half as likely to visit a dentist.

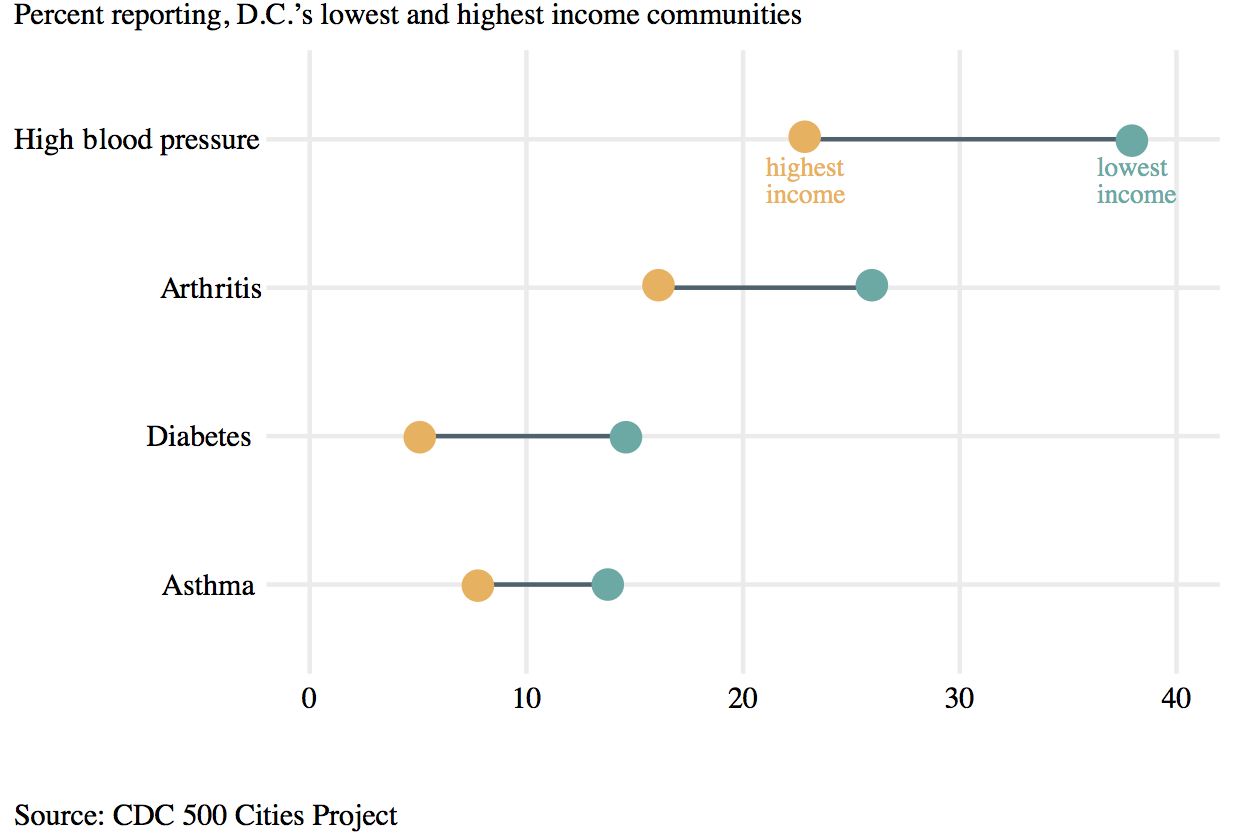

Higher rates of chronic conditions among lowest-income residents

In terms of health outcomes, residents of D.C.’s lower-income communities have higher rates of chronic diseases across the board, including high blood pressure, arthritis, diabetes, and asthma. These illnesses are rarely as well serviced as they would be in wealthier communities, and further compound the stresses of poverty.

Looking at this more detailed view of health across income groups makes clear the wealth gap that exists at nearly every stage of wellness. With D.C. ranking in the bottom half of cities for life expectancy of its poorest residents, it’s worth exploring what we can learn from the places with the best outcomes for low-income residents—including neighboring Montgomery County, which ranks third in the nation.

About the data

Health data is available through the 500 Cities project. Income data is available through the American Community Survey. You can find complete code for this post on my GitHub page.