This report is the first in a three-part series that examines the housing challenge for essential workers in the District of Columbia in the context of early childhood educators. For the purposes of this study, the term “early childhood educators” refers to educators who are working with infants, toddlers, and preschool-aged children in child-facing roles at child development centers licensed by the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). Part I looks at where early childhood educators work. Part II examines where early childhood educators live, which is often driven by affordability of housing, even if it means longer commute times. Part III closes with implications for what types of housing early childhood educators can afford given their earnings, and where housing affordability for early childhood educators exists in D.C. and the region. It also estimates the amount that would be necessary to close the housing affordability gap across different neighborhoods of D.C. for these educators.

This report is a part of a larger project at the D.C. Policy Center that examines how employers, philanthropy, and the government can create a scalable solution that can provide affordable housing for essential workers, especially those who are at the beginning of their careers.

To understand where early childhood educators work, it is first important to understand where licensed childcare in D.C. exists and what the childcare landscape looks like. The locations of child development facilities and the number of children served impact the number of educators needed to provide early childhood education services. For the purposes of this analysis, early childhood educators are defined as those working with infants, toddlers, and preschool ages in child-facing roles at child development centers licensed by the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE).

Data notes

D.C. Policy Center undertook this analysis with the purpose of better understanding where District early childhood educators live and work, what budget constraints they may face in finding affordable housing close to work, and how this differs by demographic group. OSSE shared data on early childhood educators with the D.C. Policy Center to conduct analyses addressing the research questions of this report series. Data shared by OSSE included residential address, work address, supplemental payments that early educators received from the Early Childhood Educator Pay Equity Fund in fiscal years 2022 and 2023 (when OSSE distributed payments directly to early educators via an intermediary), full- or part-time status, and job title.

Child development facilities, primarily serving children who are infants (under age one), toddlers (12 to 36 months), and preschool-aged (3 to 5 years), are important in D.C., where an estimated 39,025 children were under the age of five in 2022.1 Out of this total, an estimated 23,815 children were under the age of three, and therefore too young for D.C.’s publicly funded pre-kindergarten programs.2 An additional 15,220 children were estimated to be three and four years old, and of this group, 12,789, or 84 percent, of children were enrolled in pre-kindergarten at District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS), public charter schools, or child development centers participating in the Pre-kindergarten Enhancement and Expansion Program (PKEEP), in school year 2022-23. For both families with children under the age of three or children who are not enrolled in publicly funded pre-kindergarten, child development facilities provide a critical service. In 85 percent of households with young children, parents who live in the household are also in the labor force and are more likely to need some kind of childcare.3 Early childhood care and education from birth to age five have the potential to build a strong foundation for success later in life4 and literacy skills early on. There is also consensus that pre-kindergarten improves school readiness.5 This is especially important in D.C., where results on statewide assessments for grade 3 indicate that 26 percent of students (and only 10 percent of students who are economically disadvantaged) met or exceeded expectations in English Language Arts (ELA) in school year 2022-23.6

Families in D.C. have two licensed childcare options for early childhood education outside of their home: child development centers and child development homes.7 Child development centers—typically childcare centers, preschools, or nursery schools—serve a minimum of 12 children on premises other than the facility operator’s residence.8 Child development homes provide a child development program in a private residence for up to six children or up to 12 children if they are a child development expanded home.9

As of December 2023, the District had 459 licensed child development facilities, with a licensed capacity to serve 25,702 children ages six weeks through 13 years old.10 Focusing on the youngest children in FY 2023, 444 of these child development facilities were licensed to serve 12,424 infants and toddlers. Of these, 334 were child development centers and 110 were child development homes.11, 12 By comparison in the same year, 403 of these facilities (including some Local Education Agencies (LEAs) that provide out of school time services13) served preschool-aged children (and could also be serving other ages), with a total licensed capacity for this age group of 11,268.14 The total number of children enrolled is not available.

Where licensed child development facilities are located

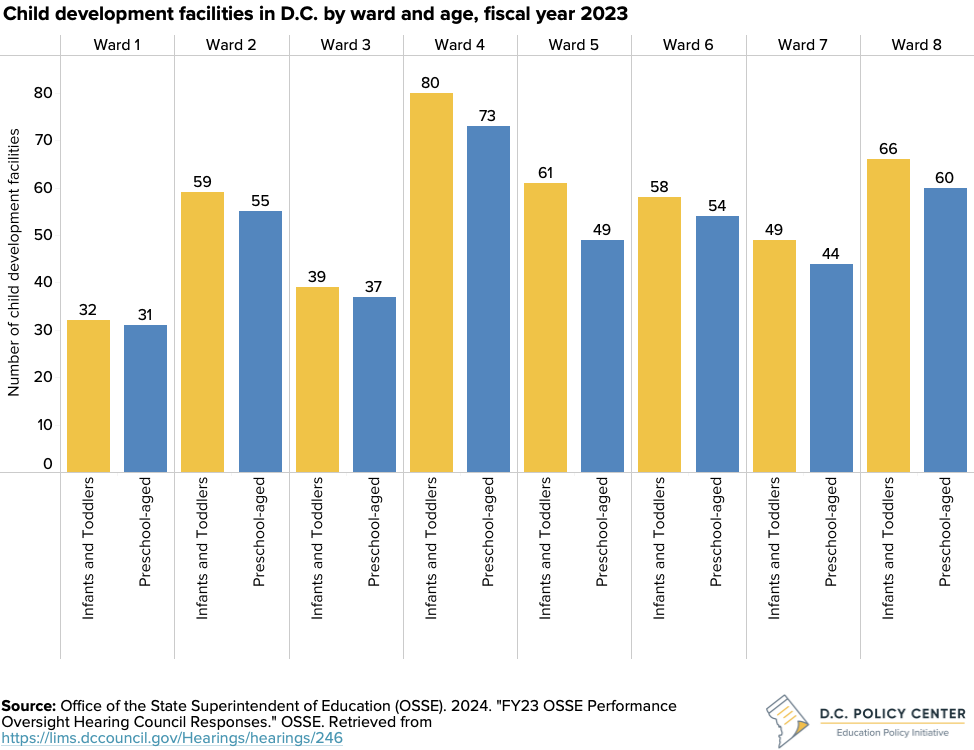

As of FY 2023, Wards 4 and 8 are home to the greatest numbers of child development facilities serving infants and toddlers, at 80 and 66 each, respectively. Wards 4 and 8 also have the highest numbers of child development facilities serving preschool-aged children, at 73 and 60, respectively (these may include facilities that serve both and are therefore counted more than once).

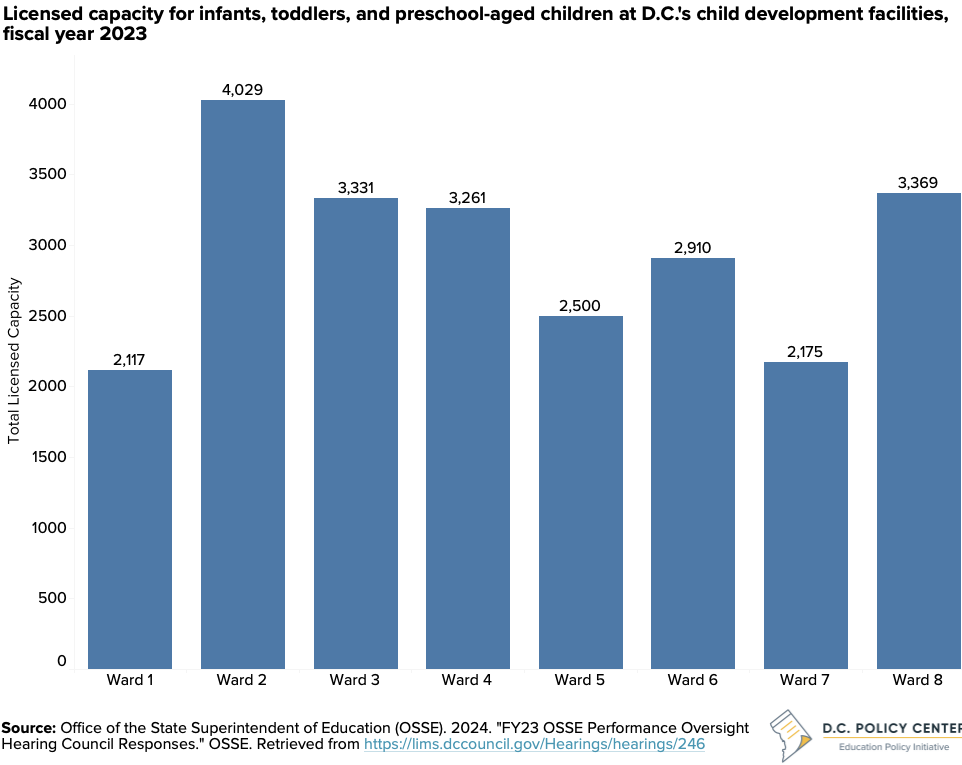

However, in terms of capacity, Ward 2 has the potential to serve the most infants, toddlers, and preschool-aged children at a licensed capacity of 4,029. Ward 3 also has a larger capacity of 3,331 children in these age groups despite having far fewer facilities than Wards 4 and 8, with a capacity over 3,000. This indicates that facilities in Wards 2 and 3 are likely to be larger and employ more early childhood educators per facility.

How the landscape of child development facilities serving children has changed over time

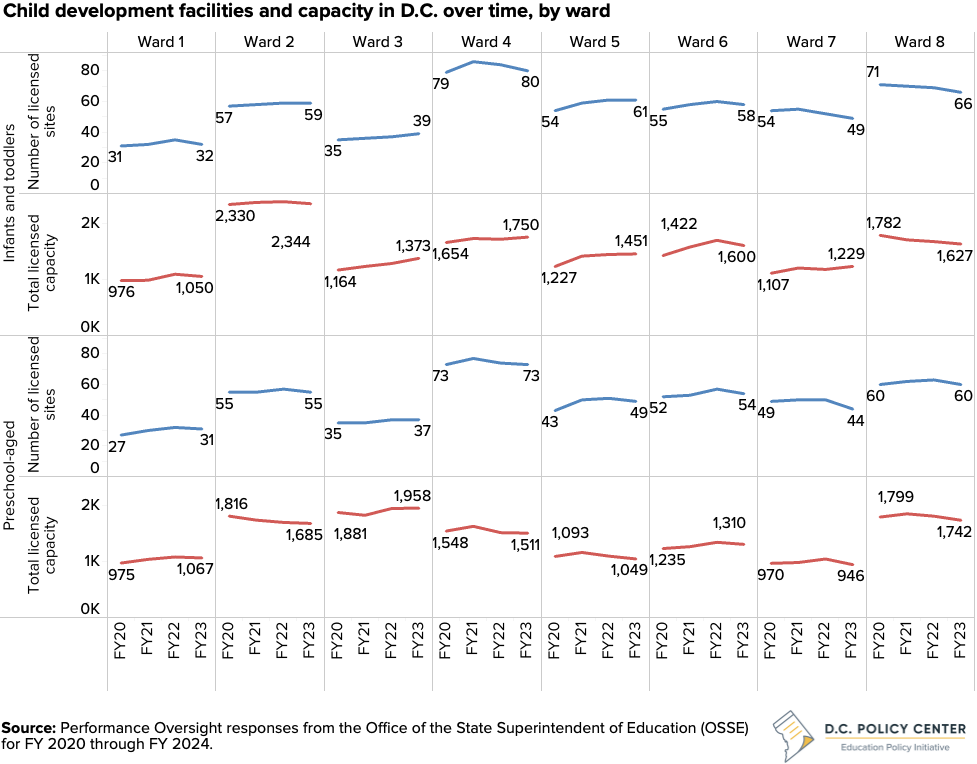

From FY 2020 to FY 2023, the number of child development facilities serving infants and toddlers in D.C. increased by eight facilities, or by 2 percent. Over this same period, available spaces increased faster: The total licensed capacity at these sites increased by 762 spaces (up by 7 percent). By ward, the number of facilities serving infants and toddlers increased in all wards except Wards 7 and 8; these wards lost 5 facilities each. For preschool-aged children, Ward 7 was the only ward with a net decrease in child development facilities that closed over this time period (decrease of 5 facilities).

Where early childhood educators work

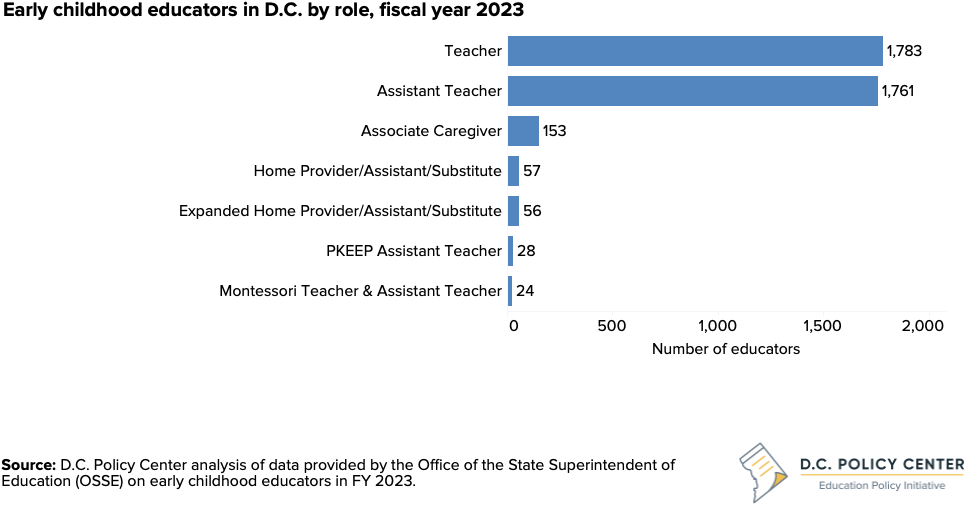

As of FY23, there were 3,862 early childhood educators15 working at child development facilities across D.C., according to data shared by OSSE (see Data Notes for more information). Most educators (92 percent) were teachers or assistant teachers, with other roles including associate caregiver, expanded home provider, home provider, Montessori assistant teacher, Montessori teacher, expanded home and home provider assistant/substitute, and PKEEP teacher and PKEEP assistant teacher.

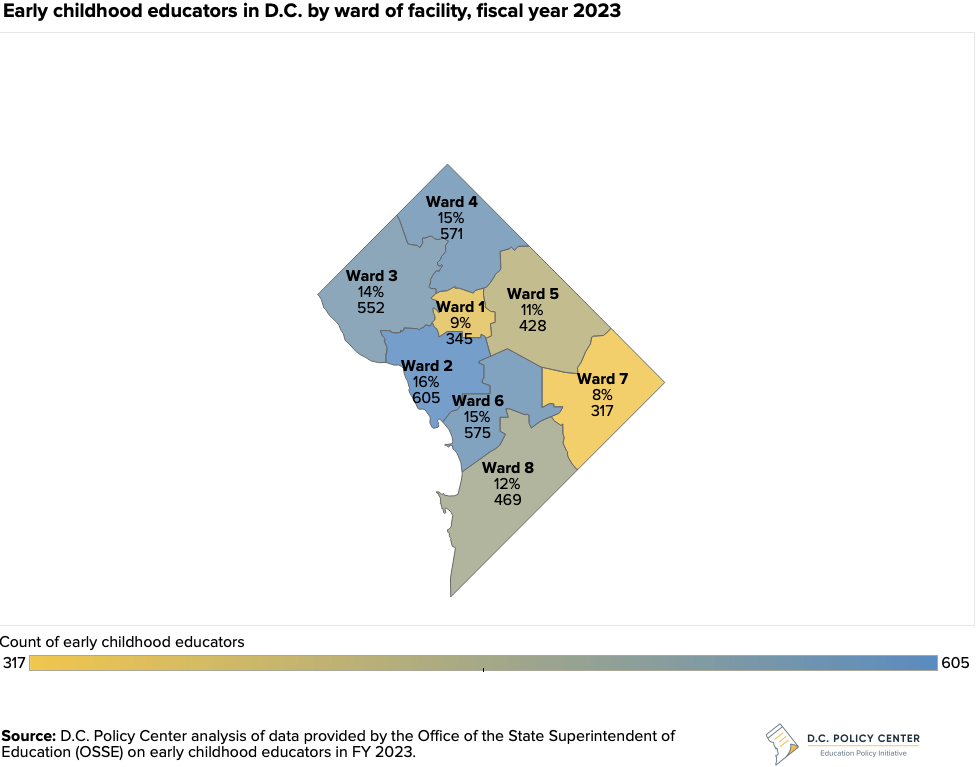

The distribution of early childhood educators by Ward of their facility shows that the highest numbers of early childhood educators are working in Wards 2, 3, 4, and 6, all with more than 500 educators each. This indicates that in Ward 8, which has one of the highest numbers of facilities, individual facilities tend to have, on average, fewer educators per facility.

Implications for commutes given where early childhood educators live will be explored in the next part of this series.

Note: This publication has been updated to reflect the correct age range for toddlers.

Endnotes

- U.S. Census Bureau – American Community Survey. 2022. “Population under by 18 years of age.” Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/table/ACSDT1Y2022.B09001?q=B09001%20&g=040XX00US11

- U.S. Census Bureau – American Community Survey. 2022. “Population under by 18 years of age.” Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/table/ACSDT1Y2022.B09001?q=B09001%20&g=040XX00US11

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2022. “ACS 5-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample.” Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/mdat/#/search?ds=ACSPUMS5Y2022&cv=HUPAC%281,2,3%29&rv=ucgid,ESP&nv=HHT%281,2,3%29,ESR&wt=PWGTP&g=0400000US11

- Heckman, J.J. 2013. “Invest in early childhood development: Reduce deficits, strengthen the economy.” University of Chicago. Retrieved from https://heckmanequation.org/resource/invest-in-early-childhood-development-reduce-deficits-strengthen-the-economy/

- Phillips, D.A., Lipsey, M.W., Dodge, K.A., Haskins, R., Bassock, D., Burchinal, M.R., Duncan, G.J., Dynarski, M, Magnuson, K.A., and Weiland, C. 2017. The Current State of Scientific Knowledge on Pre-Kindergarten Effects. Brookings Institution and Duke University. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/puzzling-it-out-the-current-state-of-scientific-knowledge-on-pre-kindergarten-effects/

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). 2023. “2022-23 Statewide Assessment Results and Resources.” OSSE. Retrieved from https://osse.dc.gov/node/1671391

- Government of the District of Columbia-Office of the State School Superintendent of Education (OSSE). 2022. “Responses to the Fiscal Year 2022 Performance Oversight Questions.”

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education. 2022. “Licensing Orientation for New Child Development Centers.” Available at PowerPoint Presentation (dc.gov)

- Ibid.

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). 2024. “FY23 OSSE Performance Oversight Hearing Council Responses.” OSSE. Retrieved from https://lims.dccouncil.gov/Hearings/hearings/246

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). 2024. “DC Child Care Subsidy Program.” OSSE. Retrieved from https://osse.dc.gov/subsidy

- Ibid.

- Out of school time services include those programs offered before or after school, over the summer, on weekends, and during school breaks or long weekends when school is not in session.

- Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE). 2024. “FY23 OSSE Performance Oversight Hearing Council Responses.” OSSE. Retrieved from https://lims.dccouncil.gov/Hearings/hearings/246

- For the purposes of this analysis, early childhood educators are defined as those working with infants, toddlers, and preschool ages in child-facing roles at child development centers licensed by the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE).