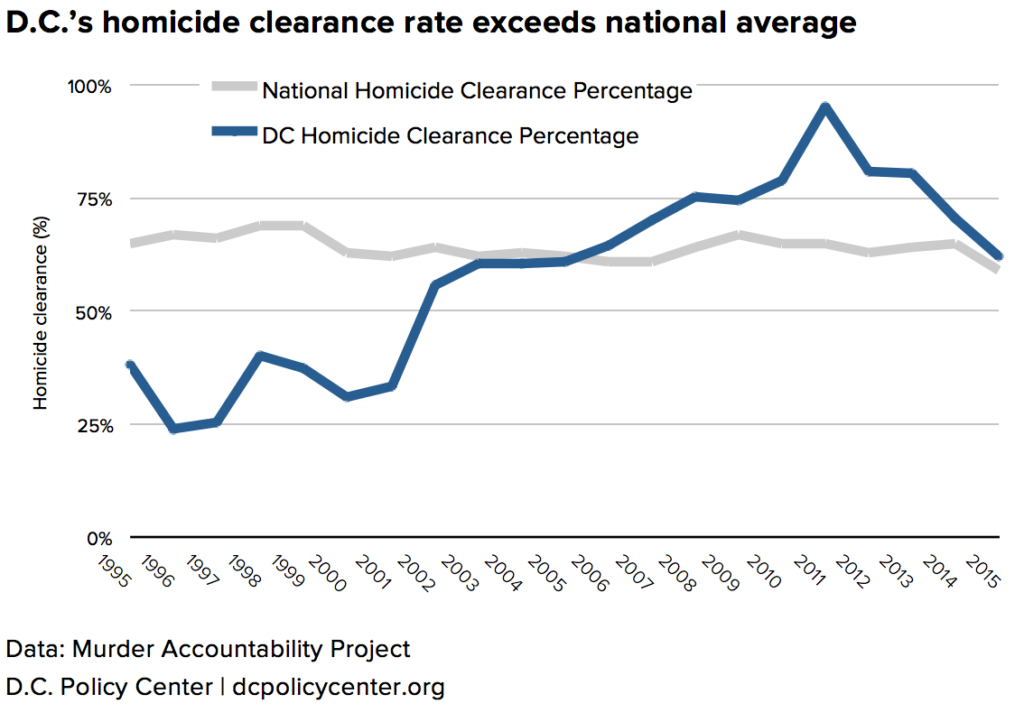

The District’s crime rates have come a long way from the “murder capital” days of the 1990s, when its per-capita murder rate was the highest in the nation. D.C.’s murder rate began plummeting in the late 1990s, as it did in cities across America, and is now one third what it was when it peaked in 1991. These days, D.C. stands out from other cities in a different way—unlike other cities, it has dramatically improved its ability to close homicide cases, defined as when an arrest has been made. In the 1990s, the District had an abysmal record at closing cases. Now it’s generally above the national average.

Police across the country, at least on average, are not all that great at catching murderers. A shocking one-third of all homicides go without an arrest a year later, and there’s been no improvement on this score since the 1990s. It’s a tragedy for the victims and their families, and a threat to the public’s safety. A lot of thought and resources have gone toward crime-prevention tactics in the past two decades, like hot spot policing and predictive analytics. But there has been little effort to ramp up resources nationally to catch criminals, even though we know that the likelihood of getting caught has a much larger deterrent effect than, for example, the length of a prison sentence.

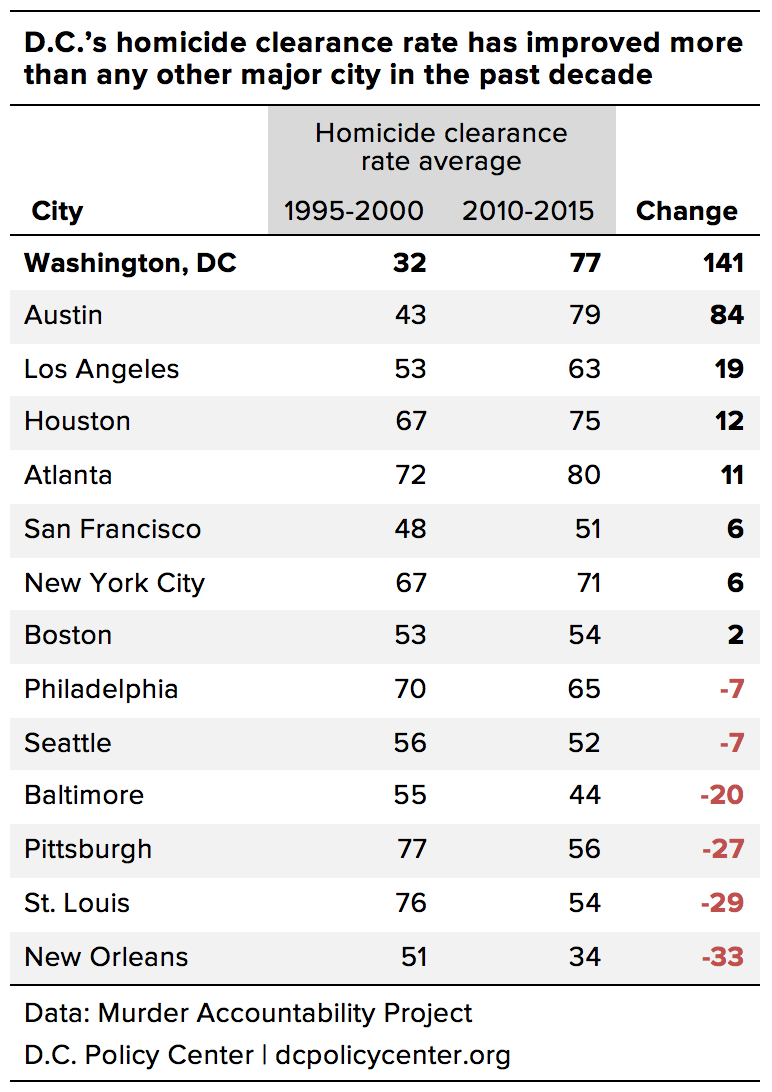

D.C. appears to have bucked the national trend. Admittedly, D.C. had a lot of room to improve. Back in the mid-1990s, just 32 percent of homicides in D.C. were cleared. Fast forward to the early 2010s, and 77 percent were cleared. That’s phenomenal improvement, not just compared to other major cities. It’s the third-biggest improvement of any jurisdiction—large or small—in the country, according to the Murder Accountability Project, which follows clearance rates closely since the FBI does not collect data on clearance. D.C. previously had a clearance rate that ranked poorly with other major cities, but it is now near the front of the pack.

We cannot attribute all of this improvement to smarter police work. For instance, the falling homicide rate in the 2000s meant detectives had more manageable caseloads, and therefore more time to devote to each case. There is also some debate about whether the more recent reported numbers overstate how much clearance rates have improved. A good chunk of the closed cases in the early 2010s were cold cases from years before that were solved using newly-available DNA technology. Cases count as “cleared” in the year they are cleared, not in the year the crime was committed. And there is some controversy over whether standards for closing cases became too loose over time. The Washington Post found that a case could be closed administratively, for example, if the suspect has died, and that “at least a dozen homicide cases were closed only days after a suspect’s death, even though the cases were months or years old.” [Update 5/10/2018: This article originally stated that a case could be closed if a key witness has died, not the suspect. This has been corrected.]

But the D.C. police department does deserve credit. They are doing a lot right, in line with research about what leads to above-average homicide clearance rates. For one, homicide clearance became a top priority for Police Chief Charles Ramsey and his successor Cathy Lanier, who collectively served from 1998 to 2017. During this time, studies on homicide clearance were commissioned. Homicide detectives got more technology and resources, including an office staffed with 24-hour data specialists who could feed detectives information in real-time even before detectives reached the scene of the crime. New layers of review were put in place, so that supervisors were keeping an eye on detective work and could offer more insights. Case files were better organized so that more eyes could keep track of their progress. Police worked harder at improving community relations, which is essential for solving gang or drug-related murders where witnesses may be more nervous about coming forward. Police were encouraged to go to more community meetings. And the reward for providing information leading to an arrest for a murder was increased from $5,000 to $25,000—a much larger reward than most cities offer.

Let’s hope D.C. can sustain its above-average clearance rate. The clearance rate dipped down to the national average in 2015, perhaps as detectives and the police force struggled to keep up with the uptick in murders for that year. But at least the days when 70 percent of homicides were not met with so much as an arrest appear to be over.

About the data

Homicide Rate data comes from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports database and Clearance Rate data comes from the Murder Accountability Project.