Will Millennials stay in the District when they start a family?

D.C. policymakers have been fighting for decades to get young people to move downtown. They sure did come, and more of them than policymakers ever expected. But the long-term growth of D.C.’s population and tax base depends on them staying into their thirties and forties—and that depends on there being enough family-sized housing that today’s young people can afford. A couple earning the region’s median income (AMI) of about $89,000 together has plenty of great urban-living, one-bedroom options.[1] But need extra bedrooms at a reasonable price for kids? Good luck, and not much that could suit them is in the construction pipeline. With policymakers focused on the more urgent housing problems facing very low-income or homeless residents, these middle-class families aren’t getting much government help either.

The demographics today

This is more than a Millennial problem. It’s a workforce housing problem. A healthy, self-sustaining D.C. community would offer housing options to all income groups and at all stages in the life cycle, from childhood to old age. Many middle-income workers understandably choose cheaper options outside of D.C. and stomach the commute. But remember that middle-income workers, like restaurant staff or bus drivers, are often those who cannot telecommute; they do “people work” or are in the services industry. More than government workers or young techies, they would probably rather live close to where they work.

Precisely measuring housing stock affordability at different unit sizes is immensely difficult.[2] But there are several telling trends that together build a compelling trail of evidence that suggests middle-income families are being left out of in modern D.C.

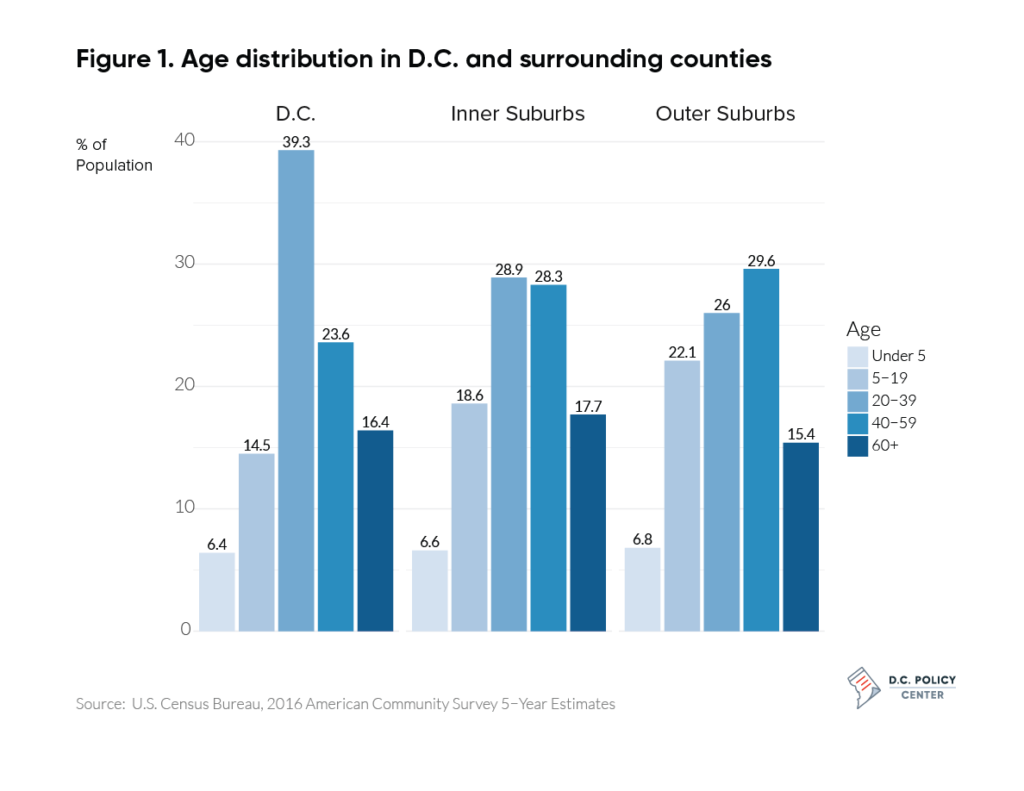

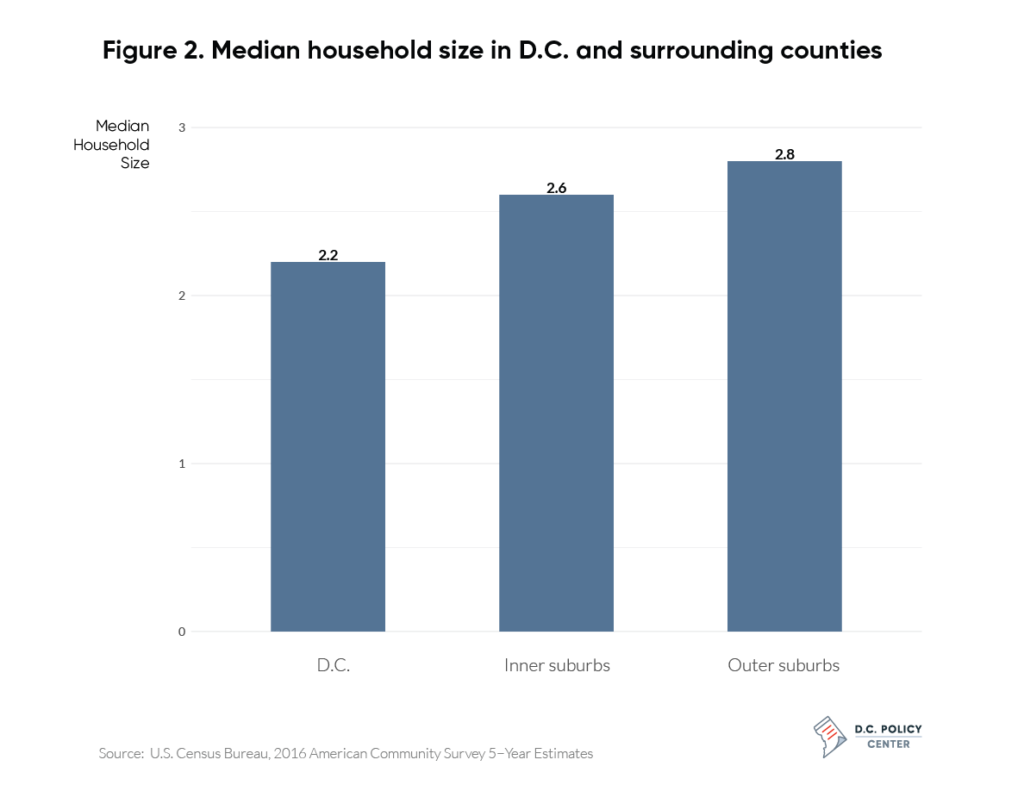

First, let’s look at the city’s age breakdown. D.C.’s age profile is different from its suburbs (Figure 1). Proportionately, D.C. has far fewer school-age kids (aged 5 to 19) and fewer middle-age adults (aged 40 to 60) compared with its suburbs. Where D.C.’s demographic bulge is clear is in the singles sweet spot—folks in their 20s and 30s. Although household size is higher than it was ten years ago, D.C. also has a smaller average household size of 2.2 (Figure 2). This is close to the smallest average household size among U.S. big cities as well.[3] D.C. remains a place where singles, not families, want to live. Concerns about school quality could be a large part of the story. But middle-income population trends suggest affordability must also be a part.

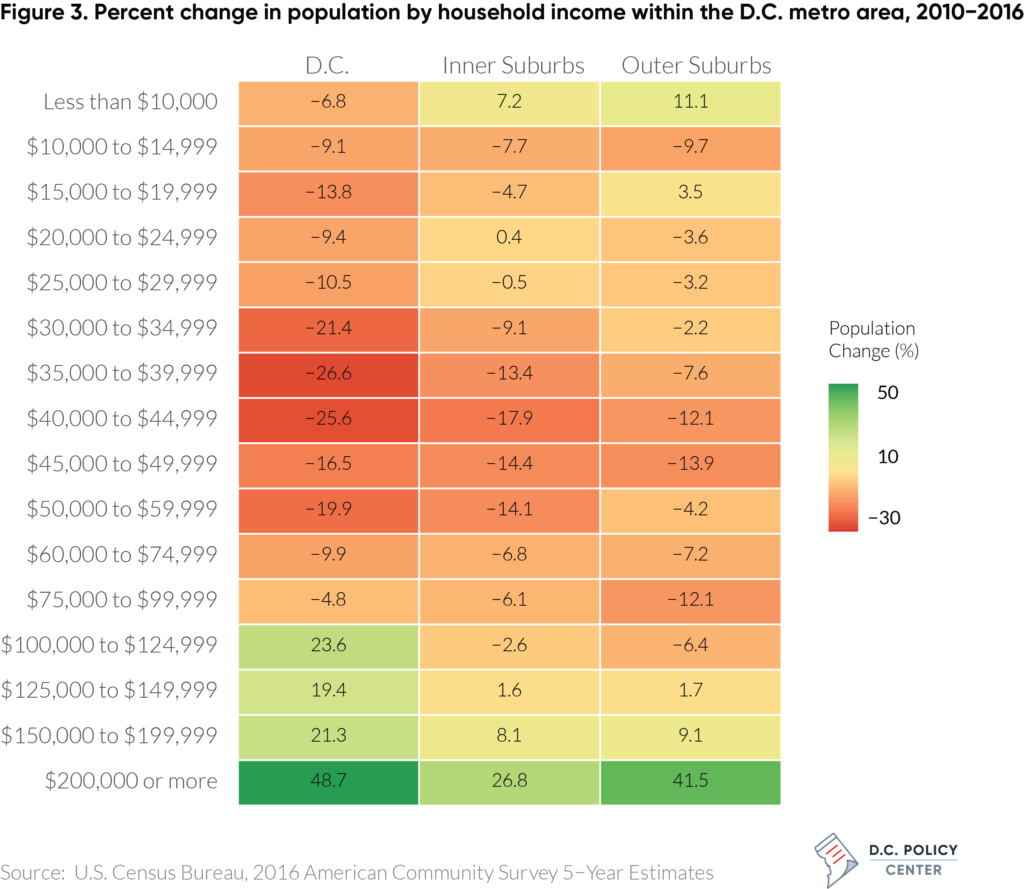

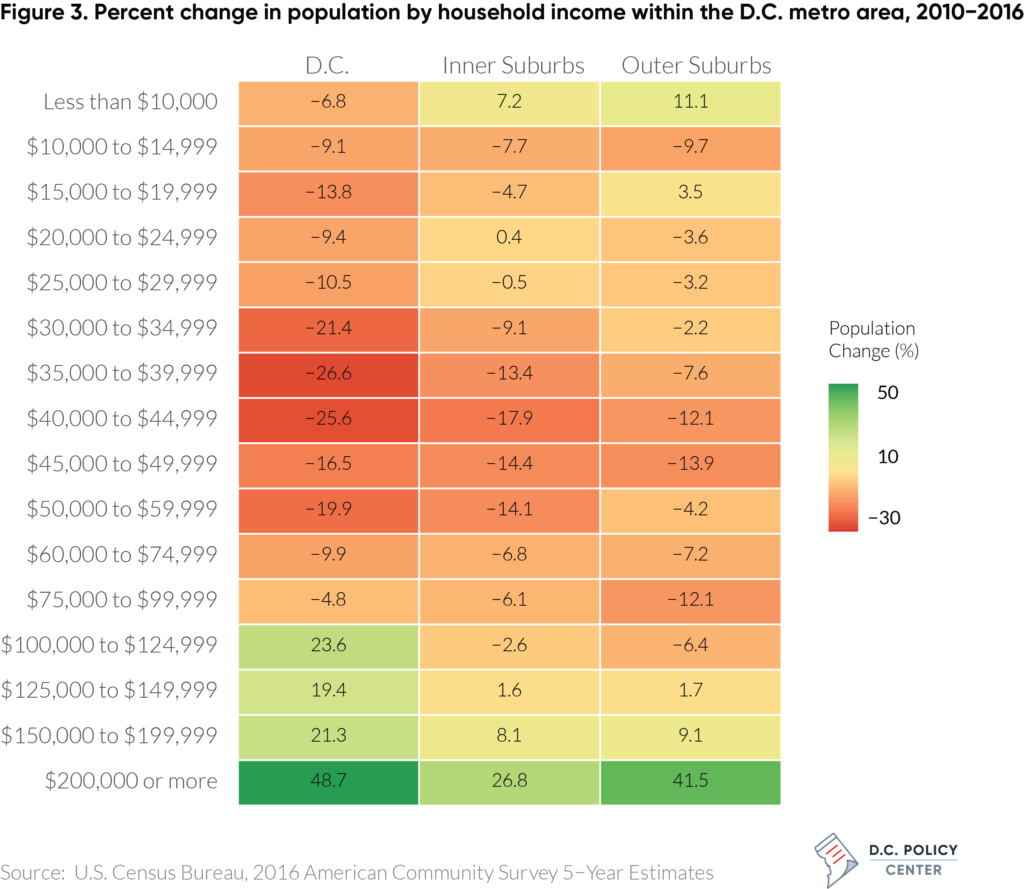

Let’s look at the city’s population share at different income levels and how those shares have changed over time (Figure 3). Again, we can see where D.C.’s trajectory veers from its suburbs. Between 2010 and 2016, D.C. saw a much steeper drop in the share of lower-middle and middle income individuals—those earning $30,000 to $60,000—than its suburbs. The middle class has been in general decline across the region. It looks to be positively fleeing D.C.

Note: % change calculated by using change in share of population, not raw estimates. Inner suburbs are defined as Arlington, Alexandria, Fairfax City, Fairfax County, Falls Church, Montgomery County, and Prince George’s County. Outer suburbs include all other counties in the D.C. metropolitan statistical area (MSA).

And now there is news confirming that many Millennials who are aging up are departing the metro region.[4] According to surveys, the number one reason why young people are leaving is housing affordability.[5]

This workforce family affordability challenge is certainly not unique to the District. Seattle and San Francisco, for example, have similar income population growth trends, demographic bulges, and small household sizes, along with a housing affordability crisis.

A future with less for families

Middle-income housing for families has not been high on the District government’s policy agenda. D.C. has among the country’s most progressive housing policies for low-income households.[6] Local and federal housing vouchers are available, and D.C. has strong tenants’ rights. To defray the cost of building affordable housing, developers can qualify for a federal tax credit and tap into a local housing production trust fund for a low-interest loan. They can also get a density “bonus” where they get to build bigger buildings if they set aside a certain number of units for low-income tenants. A lot of subsidized public housing is designed for families, too. At the opposite side of the income spectrum, homeowners (who are more likely to be wealthy) get the single biggest federal tax break on the books—the mortgage interest deduction. There are a few small D.C. government programs, for which some middle-income residents can qualify, that help cover some of the cost of a down payment on a home.[7] But middle-income renters get almost nothing from the D.C. and federal governments.

Most new construction is not so helpful, either. In the last few years, a record number of apartment buildings have been permitted, mostly going up in downtown zones where there are looser land-use regulations.[8] But these new units are expensive and small—perfect for singles, couples or roommates. The latest innovations in urban residential new construction has actually been to squeeze into less and less space—dorm-style living with shared kitchens, smaller units that cleverly feel larger or furniture that collapses.[9] Of the more than 60,000 “institutional quality” (i.e., fancy) apartments built since 2000, only about two percent have three or more bedrooms.[10] In addition, D.C.’s existing family-sized apartment stock is not equally dispersed across the city, and much of it is dedicated for low-income public housing.

The price of real estate is also pushing developers in this direction, as they can get more money per square foot for a one bedroom. Larger units would have to be so prohibitively expensive that there would be hardly any demand. D.C. actually has a lot of townhouse stock big enough for families, but those townhomes generally aren’t in the price range a median AMI couple could afford.[11] Even here, the trend in D.C. (at least up until 2015 when new regulations came into place) had been for owners to go smaller, subdividing townhouses into more profitable single-bedroom units.

In a sense, developers are responding to demand. If the city is full of singles or childless adults, perhaps the city should right-size its townhouse stock to suit this reality.[12] And some developers are betting that families prefer suburban living, complete with a yard and a minivan. Demand for urban family living simply isn’t there, they argue, no matter the price point.

The recent construction boom is not all bad for middle-income families, as any increase in housing supply takes the pressure off of overheating housing prices across the board.[13] More smaller housing units could free up housing mobility, leading to a better matching of D.C.’s housing stock with household size. If there are smaller unit options available, empty-nesters or retirees may be more willing to downsize and move out of (and free up) their family-sized houses that don’t fit them well anymore. The city, in other words, would better leverage its existing family-sized housing.

Nevertheless, the way construction is trending, the city’s housing stock will be increasingly built for childless adults. Middle-range affordability often comes from buildings aging out of their high-end cachet ten years later. The expensive brand-new units coming on the line today, in other words, are tomorrow’s slightly shabbier middle-income housing. Projecting fifteen years ahead, these units will surely be more affordable, but still not meant for families.

Is that what D.C. officials and residents want? At ANC meetings, it is a common refrain that the local leaders want more families in their neighborhoods, and they do voice those concerns to real estate developers.[14] An Urban Institute housing survey of D.C. residents indicated many worry that family needs are being ignored.[15] City planners have pledged to create a more “inclusive” built environment, usually referring to income.[16] But presumably inclusive should refer to household size as well.

There are hopeful signs that young parents might soon choose to stay in D.C. with their families. In areas other than housing, D.C. policy has become more pro-family. D.C. is one of the few American cities that offers free pre-K for three- and four-year-olds. At a value of roughly $20,000 a year, it takes the edge off of living in an expensive city. D.C. schools are also getting better. Test scores are improving, and there are more school options and in more neighborhoods. After a renovation boom, many D.C. public schools are downright palatial. Even Franklin Park—right in the heart of downtown, surrounded by office buildings—will soon undergo a multi-million-dollar uplift, which will include a kid-friendly playground. The city’s birthrate has recently ticked up, although mostly for the rich.[17]

The D.C. government can do more to make its housing market more pro-family, too, so that middle-class Millennials could see their own baby boom.

Ramping up supply

Continuing to increase the housing supply and density in general has to be part of the solution, and that’s what the 2016 changes to the city’s comprehensive plan are trying to do.[18] These changes expanded the boundaries of the downtown zone so that more big, dense apartment buildings could go up, and with less of a parking requirement. They allowed for more urban corner markets so that residents can walk to get basic groceries. And, most notably, they gave homeowners the green light to rent out extra units on their property—whether it’s a basement in a single-family home or above a garage in a back alley behind a townhouse. It’s an iron law in economics that restricting housing supply artificially drives up prices.[19] Whittling away at restrictions helps.

But the new zoning plan doesn’t do much specifically for new family-sized housing. If anything, it is prioritizing smallness. The extra unit homeowners can tack on to their property actually must, by law, be small, with no more than three occupants.[20]

The biggest steps the D.C. government has taken for families has been preservation. In 2015, the city made it harder for owners to convert multi-bedroom townhouses into one-bedroom condos.[21] The explicit aim was to protect the city’s family-sized housing stock.

If the city got more serious about expanding them, existing low-income housing programs are a good starting point. Inclusionary Zoning (IZ), which gives developers a density bonus for allocating some percent of square footage to low-income units, could be changed to include middle-income units as well, delivering truly mixed-income housing. California, for example, does this kind of mixed-income IZ.

The city could give a density bonus for family-sized units, too. Toronto, Vancouver, and Portland, Oregon have government programs that offer such bonuses. Seattle is also mulling it over.[22] In D.C. in the last few years, local ANCs near National’s Stadium and in Eckington negotiated with developers to include family-sized units in new apartment buildings. However, these deals were ad hoc. Right now, D.C. has only an income-based IZ program, not unit size-based.

Some of the best opportunities to negotiate for larger units is when the city places land it owns up for bid. In these cases, the city is more in control of the costs (and public benefits) of the project and can select whichever developer’s plan best achieves the city’s goals. The city could offer a lower price on the land, for example, if a developer builds more three bedrooms reserved for families at 100 percent AMI. The city did fight for more workforce family housing in the McMillan Reservoir redevelopment, and many of the last, large undeveloped parcels of land left in the District are owned by the city, such as the Old Soldiers’ Home, Walter Reed, or Poplar Point. These parcels may be the city’s best shot at dramatically boosting workforce housing, so the city should negotiate hard.

Most other land in D.C. is simply expensive. The government may have to outright pay to subsidize cheaper and more housing for middle-income families. The city is more flush with tax revenue than ever before, potentially opening the door to middle-income housing vouchers and tax breaks or low-interest loans for developers so that they can afford to build more mixed-income or family-sized units.

Perhaps government subsidy mixed with creative architecture could get projects to a better price point. Converting or renovating old buildings, for example, is much cheaper than new construction, which means developers can offer a wider variety of housing products and prices. The recently opened Octave in Silver Spring, MD, which had been a 1960s-era office building, is a great example.[23] Developers were able to offer like-new two-bedroom condos at a price point that a couple earning close to the regional median income could afford.

The Octave was completed without a government subsidy, but future similar conversion projects probably will need some government help. The Octave was the perfect mix of conditions that made the conversion smooth—it had been offices that were nearing the end of their useful lifecycle, it had the right floor plan for apartments, and it was close to transit. Most conversion projects won’t have such ideal conditions, and so would need a subsidy. Fortunately, D.C.’s denser corridors are already zoned in a way that allows for conversions from existing office to residential buildings with less regulatory red tape than in the suburbs. And the city’s office market has been weakening, making conversions an increasingly attractive investment.[24]

Change zoning, which changes the market

Truly sustainable and widespread affordability, however, would have to be more market-driven, and that would require a dramatic overhaul of the city’s zoning regulations and ratcheting up density across the board.[25] Ideally, Ward 3 in upper northwest D.C. would be up-zoned. It has the best schools but the lowest density compared to the rest of the city. Ideally, the Height Act would be partially dismantled to allow taller apartment buildings next to busy commercial corridors along Rhode Island Ave or New York Ave, or next to metro stops like Tenleytown, Petworth, or Cleveland Park. D.C. townhouses (ideally) would be allowed to be as tall as in Brooklyn, and more townhouses could be built in neighborhoods zoned for detached, single-family homes neighborhood—which constitute over half of D.C.’s residential land.[26]

Another option would be for the city to reimagine townhouses to marry greater density with affordable family-friendly living. Many of D.C.’s townhouses occupy only half of the lots they sit on. There is space, in other words, to double-up on townhouse density.[27] You could fit a few families on each lot in this way, each in three-bedroom units. Or you could stack the units, one on top of the other. The units themselves would be smaller than D.C.’s average townhouses, but larger than in an apartment building. The structure could be wood-frame, which is cheaper than the concrete construction of apartment buildings. There would even be some green space or a shared courtyard, creating a more semi-suburban, semi-urban community feel that many families with children prefer to tall, yard-less apartment buildings.[28]

But accomplishing all of this wouldn’t be easy or quick. The city’s zoning doesn’t have a specific set-aside for this kind of in-between density. Neighboring homeowners likely won’t want more density, for fear of what it might do to their property values. The 2016 much-hyped redo of the city’s master plan took nearly 10 years of back-and-forth negotiation with neighborhood communities and ended up leaving about 95 percent of the previous plan in place.[29]

At least there does seem to be some momentum against NIMBYism in other cities. Seattle recently managed to rezone a handful of single-family neighborhoods for denser townhouses.[30] San Francisco now has a “Yes In My Backyard” or YIMBY party with its own mayoral candidate.[31]

The city first needs to do a more comprehensive assessment of city workforce housing needs. That means collecting more data on unit size and affordability. It means meeting with communities, neighborhood by neighborhoods and along with developers, to chart out what the need actually is and what it would take to get there.

A normal city has families

D.C. has long battled to become a more “normal” city, in spite of its capital city status. That means having a truly diverse and self-sustaining, tax-paying, business-oriented economy, and not just a government or university town. D.C. has made incredible progress here, with plentiful tax revenue to prove it. But a normal city should also have a balanced and diverse city life—in every sense, which would include families at every income level.

Millennials may want a more urban family life. The city should work to make sure it can be possible, not just for the rich folks. The city has been at the forefront in many areas of progressive low-income housing policy; now it could be at the leading edge of workforce family housing as well.

Notes

[1] Kathleen Elkins, “Here’s the salary you need to afford rent in 10 of the largest US cities,” CNBC, August 15, 2016, https://www.cnbc.com/2016/08/15/the-salary-you-need-to-afford-rent-in-10-of-the-largest-us-cities.html.

[2] Claire Zippel, “To build more housing, D.C. needs more data,” Greater Greater Washington, February 27, 2017, https://ggwash.org/view/62532/to-build-more-housing-dc-needs-more-data.

[3] “Top 100 Cities Ranked by Average household size, 2009-2013,” https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/united-states/quick-facts/cities/rank/average-household-size.

[4] Aaron Gregg, “The millennials who transformed D.C. after the recession are now leaving for cheaper cities,” Washington Post, September 30, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/capitalbusiness/as-the-economy-heats-up-many-in-washington-decide-its-time-to-move-elsewhere/2017/09/30/689a3eaa-9edc-11e7-9083-fbfddf6804c2_story.html.

[5] Yesim Sayin Taylor, “Residents move into the city for jobs, move out for housing,” District, Measured, District of Columbia’s Office of Revenue Analysis, June 8, 2015 https://districtmeasured.com/2015/06/08/residents-move-into-the-city-for-jobs-move-out-for-housing-2/.

[6] Becky Strauss, “D.C. Leads in Anti-Poverty Policies,” D.C. Policy Center, April 10, 2017, https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/d-c-leads-in-anti-poverty-policies/.

[7] Two programs, for example, are D.C. Open Doors and the Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP). For more information, see https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/where-we-live/wp/2016/12/13/d-c-offers-more-assistance-to-first-time-home-buyers/.

[8] John Ricco, “D.C.’s apartment boom continued in 2016. Here’s what that means for your rent,” Greater Greater Washington, February 3, 2017, https://ggwash.org/view/62236/dc-apartment-boom-continued-in-2016-heres-what-that-means-for-your-rent.

[9] “New Co-Living Community Coming to a Secret Location in Shaw,” Washingtonian, October 13, 2016, https://www.washingtonian.com/2016/10/13/new-co-living-community-coming-secret-location-shaw/. For example, see the Oslo in Shaw: https://www.oslo-dc.com/.

[10] David Whitehead, “This map shows that in D.C., family-sized rental homes are very scarce,” Greater Greater Washington, March 1, 2017, https://ggwash.org/view/62190/this-map-shows-that-in-dc-family-sized-rental-homes-are-very-scarce.

[11] “In Washington, D.C., New Urgency for ‘Missing Middle’ Housing Types and Price Points,” Urban Land Institute, May 3, 2017, http://washington.uli.org/trends-conference-2017/washington-d-c-new-urgency-missing-middle-housing-types-price-points/.

[12] Eric Fidler, “D.C. proposes an incentive for three-bedroom apartments,” Greater Greater Washington, March 10m 2015, https://ggwash.org/view/37492/dc-proposes-an-incentive-for-three-bedroom-apartments.

[13] Joe Cortright, “The end of the housing supply debate (maybe),” CityObservatory, August 11, 2017, http://cityobservatory.org/the-end-of-the-housing-supply-debate-maybe/.

[14] Lark Turner, “Why Larger Condo Units Aren’t Being Built in D.C.,” Urban Turf, July 18, 2014, https://dc.urbanturf.com/articles/blog/if_the_district_needs_them_why_arent_developers_building_bigger_condos/8755.

[15] Pamela M. Blumenthal et al., “Strategies for Increasing Housing Supply in High-Cost Cities,” Urban Institute, August, 2016, http://nvaha.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/2000907-Strategies-for-Increasing-Housing-Supply-in-High-Cost-Cities-DC-Case-Study.pdf.

[16] “The District of Columbia Comprehensive Plan Progress Report; Moving Forward: Building an Inclusive Future,” D.C. Office of Planning, 2013, https://plandc.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/Comprehensiveplan/page_content/attachments/FINALPRINTVERSION.pdf.

[17] Perry Stein, “D.C.’s baby population is on the rise — thanks to wealthy folks,” Washington Post, April 8, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/local/wp/2016/04/08/d-c-s-baby-boom-is-driven-by-wealthy-families/.

[18] Martin Austermuhle, “D.C. Has A New Zoning Code. Here’s How It Could Change The City’s Look And Feel,” WAMU, January 20m 2016, https://wamu.org/story/16/01/15/after_eight_years_of_debate_DC_approves_new_zoning_regulations/.

[19] Edward L. Glaeser and Joseph Gyourko, “The Impact of Building Restrictions on Housing Affordability,” Economic Policy Review, June, 2003, https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/epr/03v09n2/0306glae.pdf; and Sanford Ikeda and Emily Hamilton, “How Land-Use Regulation Undermines Affordable Housing,” Mercatus Center, November 4, 2015, https://www.mercatus.org/publication/how-land-use-regulation-undermines-affordable-housing.

[20] Robin Eberhardt, “D.C. Zoning office tightens restrictions on rowhouse additions,” The GW Hatchet, June 30, 2015, https://www.gwhatchet.com/2015/06/30/d-c-zoning-office-tightens-restrictions-on-rowhouse-additions/.

[21] Ibid. More recently, the zoning code was changed so that R5 townhouse neighborhoods could subdivide into one-bedroom units, this would include for example Dupont. But for R4 townhouse neighborhoods, which are more numerous (e.g., Columbia Heights, Logan and Capitol Hill), restrictions were put in place so that subdivisions can only divide the house in half—therefore preserving family-sized or multi-bedroom units.

[22] “Family-Sized Housing: An Essential Ingredient to Attract and Retain Families with Children in Seattle,” The Seattle Planning Commission, January 2014, http://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/SeattlePlanningCommission/AffordableHousingAgenda/FamSizePC_dig_final1.pdf.

[23] Michele Lerner, “New condos in downtown Silver Spring designed for first-time buyers,” Washington Post, July 14, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/realestate/new-condos-in-downtown-silver-spring-designed-for-first-time-buyers/2015/07/13/4f0bc7b0-2017-11e5-84d5-eb37ee8eaa61_story.html.

[24] Jon Banister, “5 Challenges Facing the D.C. Office Market,” Bisnow, September 29, 2017, https://www.bisnow.com/washington-dc/news/office/5-challenges-facing-the-dc-office-market-79739.

[25] Jeannette Chapmen, “The Greater Washington Region’s Future Housing Needs: 2023,” George Mason University School of Public Policy, Center for Regional Analysis, June, 2015, http://cra.gmu.edu/pdfs/studies_reports_presentations/The_Regions_Future_Housing_Needs_2015.pdf.

[26] Neil Flanagan, “This map illustrates D.C.’s new zoning rules,” Greater Greater Washington, October 25, 2016, https://ggwash.org/view/43304/this-map-illustrates-dcs-new-zoning-rules.

[27] Archana Pyati, “In Washington, D.C., New Urgency for “Missing Middle” Housing Types and Price Points,” Urban Land Institute, April 28, 2017, https://urbanland.uli.org/development-business/washington-d-c-new-urgency-missing-middle-housing-types-price-points/.

[28] David Alpert, “We need townhouses and more to house the “missing middle,” but there aren’t enough,” Greater Greater Washington, May 10, 2017, https://ggwash.org/view/63344/dc-residents-want-townhouses-missing-middle-but-there-arent-enough.

[29] Martin Austermuhle, “D.C. Has A New Zoning Code. Here’s How It Could Change The City’s Look And Feel,” WAMU, January 20, 2016, http://wamu.org/story/16/01/15/after_eight_years_of_debate_dc_approves_new_zoning_regulations/.

[30] David Alpert, “We need townhouses and more to house the “missing middle,” but there aren’t enough,” Greater Greater Washington, May 10, 2017, https://ggwash.org/view/63344/dc-residents-want-townhouses-missing-middle-but-there-arent-enough.

[31] Alana Semuels, “From ‘Not in My Backyard’ to ‘Yes in My Backyard’,” Atlantic, July 5, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/07/yimby-groups-pro-development/532437/.

Feature photo by Ted Eytan.

Becky Strauss is a D.C. Policy Center Fellow. She has spent time at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), and is co-author of the book How America Stacks Up: Economic Competitiveness and US Policy (2016). Her writing and infographics have appeared in the New York Times, TIME magazine, Foreign Affairs, the Atlantic, Forbes, and Quartz.