Washington, D.C. is now on the front lines of the opioid epidemic. Although the District has always been an important site for the nation’s collective struggle with drugs and contests over policy and enforcement, this is a relatively new development. Deaths attributable to opioids (a category that includes prescription pain medications and street drugs like heroin) began to tick up in 2015, and in 2016 the situation went from bad to worse—thanks to the arrival of fentanyl.

The increasing presence of fentanyl in the local heroin supply marks a new chapter in the opioid crisis. First developed in the 1960s as potential substitute for morphine, fentanyl proved to be both faster-acting and about 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine. By the 1980s, it was commonly used in anesthesia and to alleviate the suffering of terminal cancer patients. Today fentanyl is a Schedule II drug and, unlike heroin and morphine, is purely synthetic—which is to say that fentanyl originates entirely in the laboratory rather than from the opium poppy. And that has critical implications for any policy response designed to confront this latest and most fatal turn in the opioid crisis.

For most of its 50-year history, fentanyl played only a minor role in the illicit drug traffic. But around 2010, the U.S. heroin market began to boom as tens of thousands of Americans hooked on powerful pharmaceutical opioids like OxyContin were driven to the black market by a sudden (and belated) tightening of the legal opioid supply. Within a few years, enterprising traffickers began to use fentanyl—according to the DEA, produced mainly in China—to stretch the heroin supply and meet the explosion in demand.

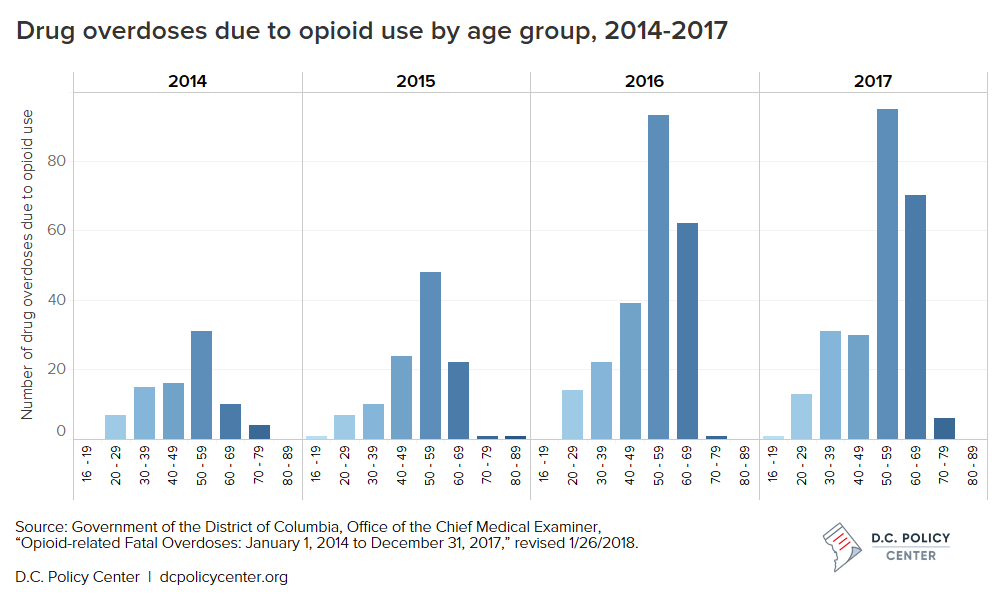

Now that fentanyl has infiltrated the regional heroin supply and arrived on the streets of the District, it’s killing an older core of experienced users—generally black men aged 50 to 70 who began using during the previous drug crises of the 1970s and 1980s, but found a way to manage their addiction for all these years. Until now.

The escalation of the opioid crisis

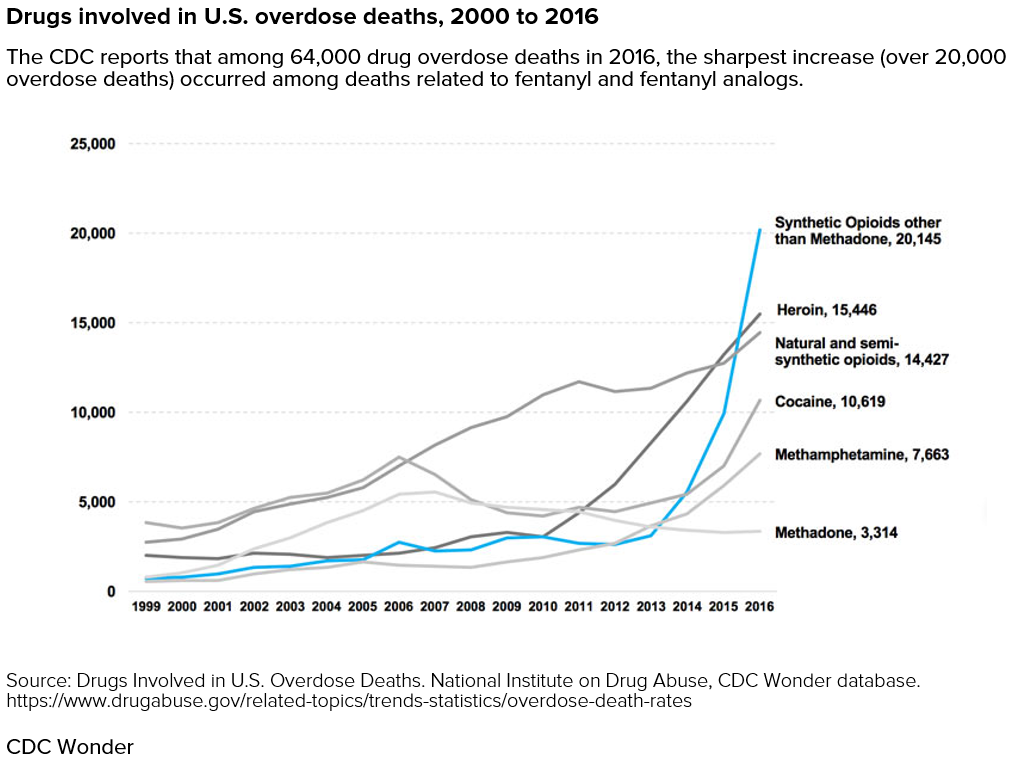

Between 2015 and 2016, the number of fatal opioid-related overdoses nationwide jumped from about 33,000 to 50,000—leading the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to declare that U.S. life expectancy had declined for the second year in a row. Fentanyl and its derivatives accounted for roughly 20,000 of those deaths—including, most famously, Prince (and more recently, at the end of 2017, Tom Petty).

In 2016, the total number of fatal drug overdoses in the United States—64,000—eclipsed both the total number of U.S. causalities in the Vietnam War and the annual mortality rate at the height the AIDS epidemic, quantitative comparisons that have become standard in discussion of the opioid crisis. The Trump White House estimates that about 175 American lives are lost to the epidemic every day.

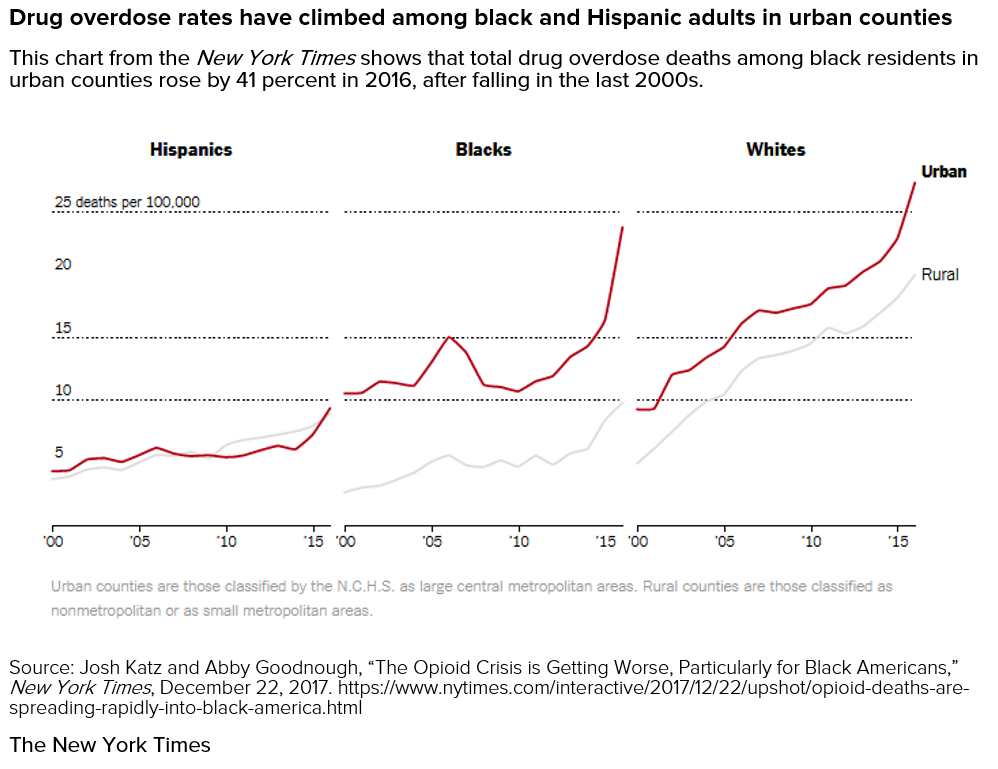

In the public mind, the opioid crisis is all but synonymous with the plight of the rural, white working class. But the opioid crisis itself is changing; as the New York Times has reported, D.C. is on the sharp edge of an increasingly urban turn that has seen overdose rates climbing precipitously among people of color and in urban counties. This turn is especially striking because the rate of drug overdose deaths among black Americans had fallen in the late 2000s before rising sharply in recent years.

The crisis in D.C.

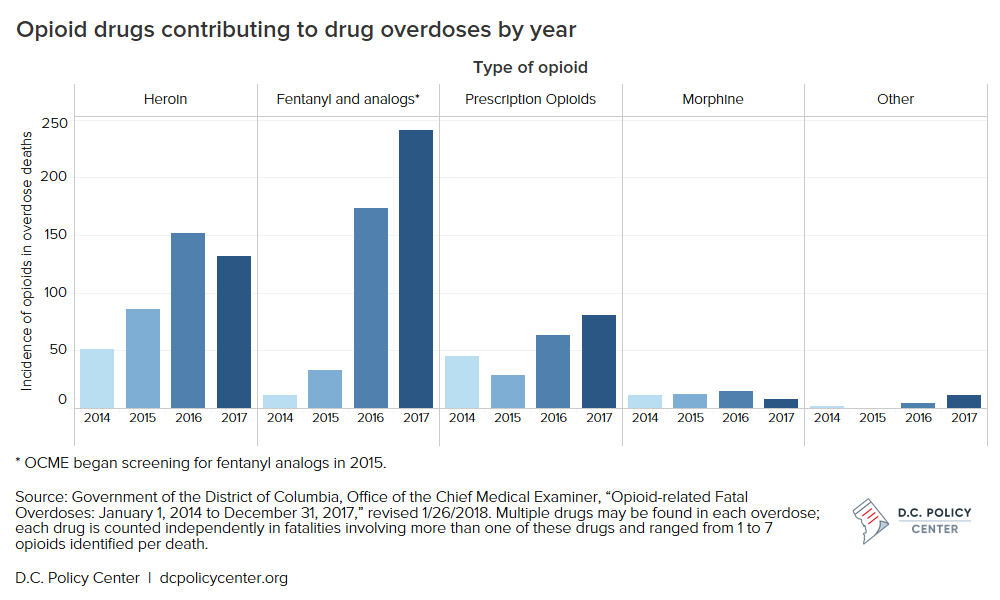

Here in the District, the lethal progression from 2015 to 2016 was even more dramatic than national trends: the city’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) reported a 100 percent increase in fatal narcotic overdoses, from 114 to 231. In age-adjusted per capita deaths, that puts the District on a level with Ohio, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania—states that have been ravaged by the crisis. Only West Virginia faces a higher rate of overdose mortality.

OCME’s provisional count of the 2017 data indicates that the crisis continues to grow. Although the rate of increase slowed, the number of fatal drug overdoses in the District climbed to 246. Overall, OCME has investigated 674 deaths due to the use of opioids from January 2014 to December 2017.

OCME data shows that the vast majority of people who died from opioid-related overdoses in D.C. in 2017 were adults ages 40-69 (an older age range than national averages); almost 40 percent were adults in their fifties. Eighty one percent of people who died from opioids were black, and 74 percent were men. Many of these deaths are concentrated in the eastern half of the city—with 54 deaths in Ward 8, 37 in Ward 5, and 37 in Ward 7—reflecting D.C.’s well-established geography of inequality.

In many respects, D.C. is facing a heroin and fentanyl crisis, rather than an opioid crisis. Legal opioid-related overdoses continue to grow, but they have been dwarfed by the number connected to heroin and fentanyl. It’s also worth noting that the city has managed to avoid the uptick in violence that often accompanies a surging illicit market; the overall crime rate is down, with violent crime dropping 22 percent and property crime falling 9 percent between 2016 and 2017. Opioids are a problem, but it was fentanyl, specifically, that tipped the city into crisis.

As journalist Candace Y.A. Montague reported in Washington City Paper, the introduction of fentanyl into the local heroin supply has had a devastating effect in D.C. It appears that most of the older African American men now experiencing a high rate of overdose likely began using in their youth during the 1970s and 80s and continued to use heroin into the present, managing to settle into a rough equilibrium with their addiction. Dr. Tanya A. Royster, Director of D.C.’s Department of Behavioral Health, told City Paper that “these new things are introduced into the opioid supply, like fentanyl and some of the other synthetics, they are much more lethal and much more deadly. So what they have been doing for the last 20 or 30 years is not necessarily safe.”

Also of note is the relatively small number of “undomiciled” overdose victims—which suggests that D.C.’s population of experienced users generally have stable housing and even steady employment. In other words, this cohort of confirmed heroin users found a way to cope with their addiction and lead otherwise normal lives until the arrival of fentanyl.

Note: Drug-related deaths may involve more than one substance, and counts of deaths related to specific substances do not sum to the total number of deaths.

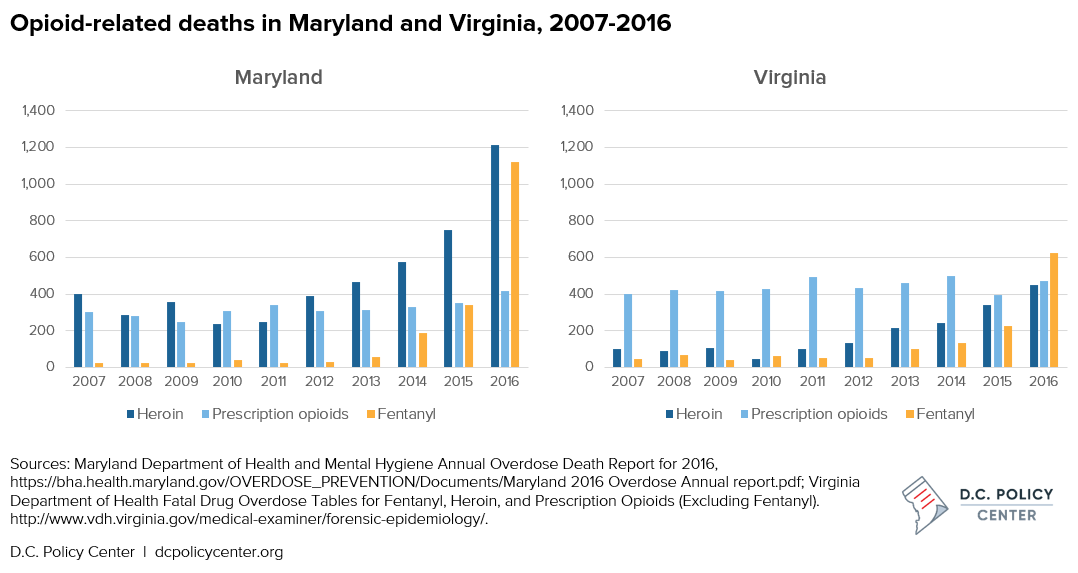

Elsewhere in the region, Maryland closely trails the District in age-adjusted per capita overdose deaths and has also seen an alarming jump in fentanyl-related overdoses. Yet even with majority black Baltimore accounting for a disproportionate share of Maryland’s overdoses deaths (roughly equal to the rest of the state combined), the overall trend remains distinctly younger and whiter than in the District. Virginia does not offers a corresponding demographic breakdown, but there the crisis appears to be growing more slowly and concentrated in the D.C. suburbs and along the West Virginia and Kentucky borders.

Understanding the epidemic

In a larger historical sense, the story in D.C. today reverses the traditional narrative around most drug epidemics, in which drugs are typically an urban crisis that spills over to claim white suburban victims. What we are seeing now is essentially the reverse: As fentanyl and other synthetic narcotics have supplemented the heroin market to meet the demand created by legal opioids, the sharpest increase in overdose deaths is among black and urban populations. Nationally, D.C.’s Chief Medical Officer Dr. Roger Mitchell Jr. has noted, the typical user who experiences an opioid overdose is a white person between the ages of 20-45 who likely began using heroin after becoming hooked on prescription pain medications. But D.C.’s victims of the opioid epidemic do not fit that picture.

D.C.’s population of long-term heroin users also demonstrates that many commonly-accepted views about addiction in America are wrong. In High: Drugs, Desire, and a Nation of Users, Ingrid Walker argues that our national discourse tends to paint drug use and addiction as either a medical phenomenon or a criminal one: Substance abuse is seen as either an unfortunate consequence of medical treatment or a product of vice and moral failure. Yet that polarization obscures a range of moderate drug use patterns, and D.C.’s core of long-term heroin users is a particularly striking example of the normalized use of a drug that media depictions and popular opinion typically see as an unqualified menace that is impossible to use in moderation.

The fact that many of D.C.’s older heroin users began in their youth illustrates the long-term effects of any drug crisis. In 2018, the city is still grappling with the consequences of the epidemics of the 70s, 80s, and 90s. As Dr. Andrew Kolodny of Brandeis University’s Heller School told the New York Times, “Forty, 50 years later we’re still paying a price. What this means is for our current epidemic, we’re going to be paying a very heavy human and economic price for the rest of our lives.”

In a more immediate sense, the complexion of D.C.’s most vulnerable population complicates any public health response because it is typically much harder for people of color to access healthcare and treatment options. In theory, outreach and treatment should be easier among more dense urban populations. But here again, D.C.’s geography of inequality means there are far fewer medical resources in the eastern half of the city—look no further than the on-going saga of the limited obstetrics services in eastern D.C. Basic searches on Google and Yelp suggest that drug treatment facilities in the District tend to be clustered downtown, with relatively few in Wards 5, 6, 7, and 8, where the crisis is most concentrated.

Treatment must be easier to access than street drugs.

One hundred years of failed drug prohibition suggest that law enforcement will not vanquish the heroin market any time soon or successfully hold the menace of illicit fentanyl supplies at bay. Meanwhile, the near total inaction on the part of the Trump Administration—despite the declaration of a public health emergency back in October—means that little help will be forthcoming from the federal government.

It will take federal dollars—and a concerted public health effort—to finally beat back the opioid crisis, but local policy makers shouldn’t look to the federal government for leadership; cities now have an opportunity to implement a fresh approach. Philadelphia, for example, just became the first U.S. city to officially support safe injection sites, a laudable step in the direction of harm reduction strategies that have proven effective in confronting other public health emergencies. However, each city must chart its own path. In Philly, one of the sharpest aspects of the problem is drug use among the city’s homeless population, which is why safe injection sites are a priority. That’s less of an issue in D.C., where homelessness plays only a marginal role in the city’s drug problem.

The real lesson from Philadelphia is the importance of outreach. A major purpose of safe injection sites is to provide a regular point of contact between drug users and health services—and that may well be the key to solving the crisis. If most of D.C.’s heroin users are using in their homes or other private spaces, it will be necessary to employ a more active style of community outreach to draw them into treatment programs. Former users who know the shifting geography of the retail drug market and the rhythms of illicit use will be critical allies and interlocutors. A new report from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health reveals that distributing inexpensive test strips to check for the presence of fentanyl in street drugs could dramatically reduce the likelihood of overdose.

For D.C., the best approach is an active outreach campaign backed by the availability of medically-assisted treatment (MAT). The city is already doing a commendable job of equipping its first responders with naloxone, a drug capable of reversing an acute overdose. But more must be done, and on a long-term basis. D.C.’s older heroin users have sustained their drug use for decades. They are unlikely to stop without a viable, convenient, and effective alternative.

Providing this alternative is not a new strategy: methadone has been used to stabilize and withdraw heroin users since the late 1960s, but clinics often run afoul of the NIMBY politics of many communities. Newer therapeutics like buprenorphine offer even greater promise, in part because they can be taken in privacy and are free of the stigma and inconvenience attached to a daily visit to a methadone clinic. Maintenance drugs are not a cure-all and are not without risk. Both methadone and buprenorphine have been found in the toxicology screens of overdose victims, indicating that MAT alone is not sufficient to break heroin’s hold on some users. But the severity of the crisis demands a renewed effort.

Ultimately, the best approach to confronting the opioid crisis is to lift the social stigma around addiction and provide clear and easily accessible paths to treatment. If there’s a silver lining to the crisis in D.C., it’s in the remarkably low number of overdose deaths among individuals under age 30. Generations of failed drug war policy demonstrates that harsh taboos and militant policing have done little to stop the drug crisis, and the city must act soon to prevent the epidemic from spreading to a new generation. D.C. now has an opportunity join other cities in leading the nation in a new humane and effective direction.

Update: Read more about how the D.C. region is responding to the opioid epidemic.

About the data

Data on opioid overdoses in D.C. is from the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) report Opioid-related Fatal Overdoses: January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2017 (January 22, 2018, revised January 26, 2018), prepared by Dr. Chikarlo Leak. Previous reports are available here.

Data on opioid overdoses in Maryland is from the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s Annual Overdose Death Report for 2016.

Data on opioid overdoses in Virginia is the Virginia Department of Health‘s Fatal Overdose Tables for Fentanyl, Heroin, and Prescription Opioids (Excluding Fentanyl).

Matthew R. Pembleton is the author of Containing Addiction: The Federal Bureau of Narcotics and the Origins of America’s Global Drug War (UMass Press, 2017) and teaches at American University. He is also a history consultant at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Follow him on Twitter at @mattpembleton.