Public transportation in the national capital region consists of Metrorail, buses, and some commuter trains. In between, there are substantial gaps in coverage: some in-demand neighborhoods have no rail service at all, especially Georgetown, whereas the service that does exist is often overcrowded, especially the Orange Crush in the morning from Arlington to the District. There is also poor crosstown service, so the only way between most pairs of neighborhoods is through the downtown transfer points.

Two specific proposals call for addressing some of D.C.’s transportation problems by introducing new modes of transportation into the region: an aerial gondola, and a ferry system going up and down the Potomac.

The supporters of the aerial gondola have a detailed website explaining their plan to connect Georgetown with Rosslyn, giving Georgetown a connection to Metrorail across the river at much lower cost than building the separate Blue Line plan with a new underground station in Georgetown. Today, Georgetown is far from Metrorail, separated by rivers and long walks, and the gondola would connect it to the Rosslyn hub.

At the same time as the gondola proposal, the local chapter of the American Institute of Architects is proposing a different way to cross the water: ferries, also known as water taxis. With 31 terminals on both sides of the Potomac, the AIA’s proposed ferry would connect the Navy Yard, Georgetown, Alexandria’s Old Town, and many smaller sites along the waterfront, bypassing Metrorail crowding.

But a careful comparison suggests that neither gondolas nor ferries are a good solution to the transportation problems of the District and the surrounding area. Each of these two modes works in a specific set of uncommon circumstances, which do not occur in or around Washington. They both look like novelties (gondolas look especially sleek), but they are unlikely to get substantial ridership or to relieve overburdened Metrorail lines.

Instead of spending money on installing these new modes of public transit, the region should embark on a more boring solution: improve Metrorail and Metrobus. If there’s money for extra operating costs for gondolas and ferries, then there’s money for higher frequencies on existing transit. Metrorail no longer has the coolness factor that new modes of public transportation has, but it’s the region’s workhorse and always will be.

What are gondola lifts?

Gondola lifts are rare as ordinary public transportation; they are more commonly used for tourism, as at many zoos and ski resorts. However, examples of ordinary usage exist. Medellín and Mexico City have systems connecting neighborhoods high in the mountains, where conventional road and rail transportation would be circuitous. Closely related aerial tramways, which have slightly different propulsion (precluding more than two stations) but are suspended by cables like gondolas, have a number of additional examples, including New York’s Roosevelt Island Tramway and the Portland Aerial Tram.

The costs of both aerial tramways and gondola lifts appear comparable with those of light rail. The Portland Aerial Tram cost $57 million in the mid-2000s for 3,300 feet of horizontal distance, the first Medellín Metrocable line cost in today’s money about $55 million for 1.3 miles, and Mexicable cost about $170 million adjusted for living costs for 3.1 miles.

The average speed of gondolas is quite low. Mexicable averages 13.5 miles per hour, Metrocable averages 11, the Portland Aerial Tram averages 12.5, and the Roosevelt Island Tramway averages 12. The main reason to prefer them to more usual public transportation is that they require very little infrastructure between the stations, and can climb steep slopes. Roosevelt Island has no bridges connecting it to Manhattan, and at the time the Tramway was built had no subway connection, either; the other three examples involve mountains.

Finally, the capacity of gondolas is limited, like that of a streetcar. A 2011 French review (in English) of both aerial tramways and gondolas finds that aerial tramways are comparable to buses, and gondolas are comparable to light rail systems with short trains, about 100 feet long, or to a single car’s worth of Metrorail service. The same review quotes operating and maintenance costs that appear to be on a par with those of metro rail systems providing equivalent capacity.

A 2008 review for Reconnecting America, focusing on lower-capacity aerial trams, suggests that this mode of transportation is best suited for environments that need just two stations, separated by a difficult obstacle such that straight-line travel is feasible.

Although the costs appear comparable to those of light rail, it is not easy to build gondolas in lieu of conventional light rail and metro systems, since the scale of conventional urban rail is well beyond the maximum size of any gondola lift. Gondolas have limited speed compared with nonstop rail lines over the same distance, and require considerable time for passengers to climb up and down the stations over such a short distance; they are unlikely to offer any travel time benefit when they are suspended over city streets.

Can gondolas work in Washington?

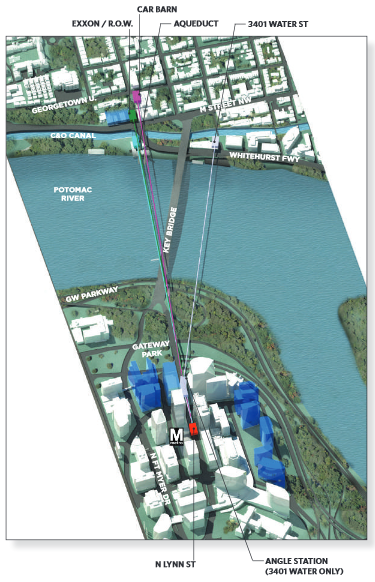

The proposed gondola lift in Washington would connect Georgetown with Rosslyn. According to the feasibility study prepared by the advocates of the project, it would run from the Rosslyn Metrorail station on the Virginia side to a site off the D.C. waterfront near the university campus. By making it faster and easier for Metro riders arriving in Rosslyn to cross the river into Georgetown, the feasibility study claims that it would vastly increase the areas of the metro region where residents could reach Georgetown within 30 minutes by public transit.

One of the proposed gondola corridors

This proposal is unlikely to work, for several reasons.

First, the gondola station on the D.C. side wouldn’t be sufficiently integrated into the local public transit network. The Georgetown station would be near the Georgetown University campus—convenient for students, but for few other people. The commercial center of the neighborhood is at the intersection of Wisconsin Avenue and M Street. The entertainment and non-university jobs cluster there, and the main bus route, the 30 series, runs down Wisconsin; the only bus serving the proposed station, the G2 to Dupont Circle and Howard University, runs fairly infrequently. Without the frequent bus connection to the 30 series, the gondola would not really be able to serve the residential parts of the neighborhood.

Second, the gondola wouldn’t necessarily save passengers much time over walking. The Rosslyn Metrorail station is deep underground, and the gondola is high above ground. The feasibility study adds a 2.5 minute transfer penalty but assumes no walking time if the gondola station is right on top of Metrorail; in reality, transfer time would take longer, as just going up and down elevators and escalators would add a substantial travel time for passengers. On most trips this is not a major problem, but on short trips this could cancel the travel time benefit over just walking. This alone would make the gondola slower as a Metrorail connection between Arlington and Georgetown than walking to Foggy Bottom from Wisconsin and M.

Third, according to the Census Bureau’s OnTheMap tool, there isn’t much work travel demand between Georgetown and Arlington. There are 5,500 people living in Georgetown working in Downtown D.C. and 2,100 people commuting in the reverse direction. In contrast, there are only 1,200 people living in Georgetown commuting to Arlington or Alexandria, and 5,000 commuting from Arlington or Alexandria to Georgetown, of whom only about 2,200 work at or near campus. For Downtown-bound travelers in Georgetown, the gondola would be backtracking, going outward to Virginia to go inward to city center, which would not provide any travel time benefit over walking to Foggy Bottom.

And fourth, if the gondola did encourage more people to commute in to D.C. by Metro, the few riders who would elect to use the gondola between Georgetown and Rosslyn would overload the rail network. The Rosslyn station already experiences overcrowding, and extra passengers would make it even worse. Walking to Foggy Bottom does not have this problem, first because many jobs are already within walking distance of Foggy Bottom, and second because according to WMATA’s data release on station use by time of day, Foggy Bottom is a destination station much more than a residential origin station: 10,900 passengers get off every morning and 2,200 get on.

Ferries and water taxis

If gondolas are not a good mode of transportation for the region’s needs, then what about water taxis, also known as ferries? International public transportation consultant Jarrett Walker offers several guidelines for best practices:

First, ferries should run frequently. For example, the Staten Island Ferry in New York comes every 15 minutes at rush hour and every 30 minutes off-peak, taking about 25 minutes in each direction. To facilitate high frequency, the ferry should connect one major terminal on each side of the river or harbor, rather than offering many routes connecting smaller terminals.

Second, there should be high density and good transit connections next to the waterfront so riders can easily get to their destinations. The Staten Island Ferry’s Staten Island terminal has a connection to the Staten Island Railway, while its Manhattan terminal, South Ferry, connects to two different subway lines and is walking distance to many of the skyscrapers of the Financial District. Another positive example is Vancouver’s SeaBus, which connects Waterfront terminal, next to the skyscrapers of Downtown Vancouver, with a bus terminal in North Vancouver.

Third, ferries shouldn’t run alongside bridges or tunnels, as these faster options would compete with the ferry for riders. Staten Island is only connected to Manhattan by bridges passing through Brooklyn or New Jersey, with circuitous routes, no service to the Island’s densest area, and slow traffic. North Vancouver has bridges to Vancouver, but far from Downtown. Ferries are not a fast mode of transportation, averaging about 12 miles per hour in New York and Vancouver, and city buses on bridges are typically faster (one bus in New York that exclusively runs on the Williamsburg Bridge between Manhattan averages 16 miles per hour), let alone cars, express buses, or trains.

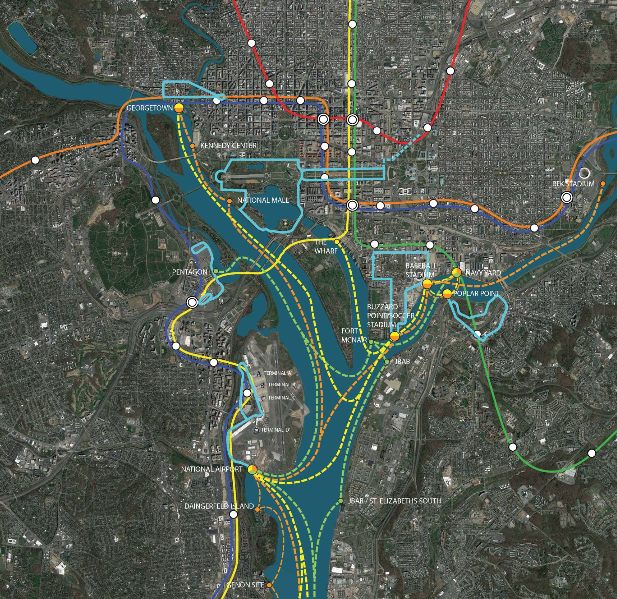

Unfortunately, the proposed Potomac River Transportation Framework Plan fails all three criteria. Here is the service map:

Any ferry system in Metropolitan Washington has its work cut out for it. Unlike in New York, there are no big waterfront job centers; Metro Center and Farragut are well inland. Georgetown has some density near the waterfront, but the buildings are separated from the water by the Whitehurst Freeway, and besides, the neighborhood is not connected to Metrorail. There’s some existing density in Old Town in Alexandria and growing development near the Navy Yard, but neither location has good Metrorail or bus connections; the Navy Yard Metrorail station is about a quarter mile from the waterfront.

The water taxi plan makes things worse, by splitting ridership across many small terminals, precisely what Walker cautions cities to avoid. There are two different Navy Yard terminals and another terminal at Buzzard Point. There is a terminal at Potomac Yard, within walking distance of very low-density suburbia. The situation today is actually better: the water taxis serve one central location on the Southwest Waterfront, a quarter mile from the Waterfront Metrorail station.

Worst, the proposed ferries mostly run alongside the river rather than crossing it. Connecting Alexandria with the Navy Yard means running the ferry parallel to the river for most of the way, forcing it into competition with the faster Yellow and Green Lines.

A ferry would be most useful if there were more development right along the waterfront in the District. Unfortunately, the most promising waterfront locations have big obstructions on the way: the Air Force base in Anacostia, Reagan National Airport in most of Alexandria, and relatively low commercial density on the Southwest Waterfront.

The alternative: Improving existing service

Gondolas are a poor fit for Georgetown’s needs: Georgetown needs a Metrorail connection, and a gondola would deliver a connection that would be slower than walking to Foggy Bottom for most trips. Ferries are a poor fit for the region’s needs as well: there are too few high-density waterfront areas that ferries would connect well to. These two modes have their role to play in some cities, but in the Washington region they are unlikely to succeed.

Instead, the region should spend more money on improving the existing rail and bus systems. It can reorganize the bus system (especially east of the Anacostia). It can also add more service to both the bus and Metrorail networks. Off-peak frequency on Metrorail today is a train every 12 minutes (15 minutes on Sundays), and the trains are not reliable. If there is money for the high operating costs of ferries, then it should go toward improving off-peak frequency; if there is money for capital construction for a gondola, then it should go toward upgrading Metrorail signals to allow more trains to run at the peak, when the system is overcrowded.

Feature photo by Ted Eytan (Source)

Alon grew up in Tel Aviv and Singapore. He has blogged at Pedestrian Observations since 2011, covering public transit, urbanism, and development. Now based in Paris, he writes for a variety of publications, including New York YIMBY, Streetsblog, Voice of San Diego, Railway Gazette, and the the Bay City Beacon. You can find him on Twitter @alon_levy.