Black women across the U.S. are starting businesses at six times the national average. According to a 2018 report commissioned by American Express, there are 2.4 million businesses owned by Black women nationally, and Black women actually have higher shares of business ownership than Black men.[1] Yet at the same time, Black women founders receive less than one percent of venture capital deals, and receive lower loan amounts at higher interest rates than other founders.

The District of Columbia is ranked as the top city globally for entrepreneurial talent by the 2019 Global Talent Competitiveness Index, but this ranking masks deep inequities in access to the financial resources necessary to become an entrepreneur. When it comes to wealth and income, D.C. is one of the most unequal places in the country—and prospects are particularly poor for Black women.

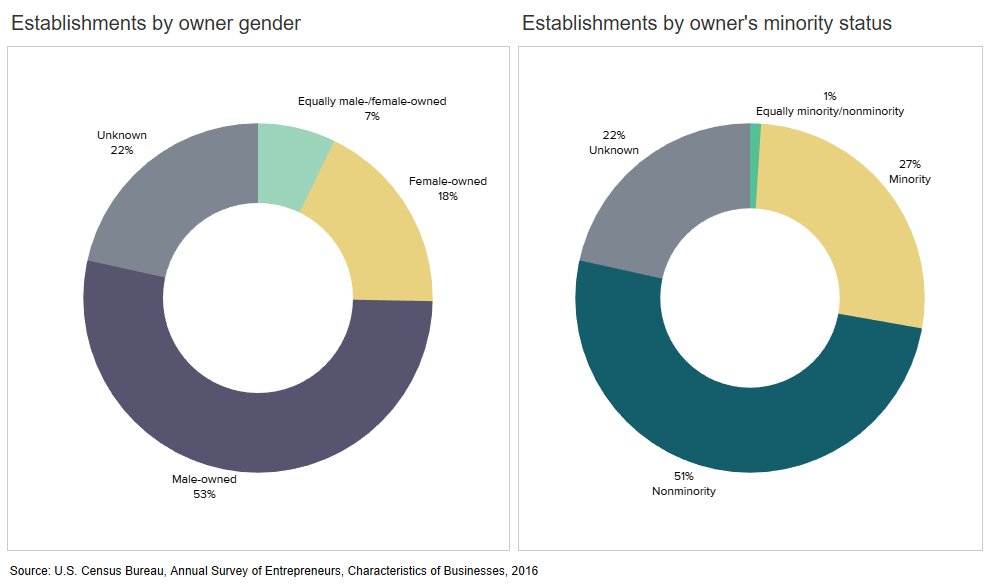

Just 18 percent of all business establishments in D.C. are reported to be owned solely by women, and only 27 percent are owned by people of color.[2] These businesses are much smaller, too, both in terms of their gross receipts and in terms of how many people they employ. Without the resources and networks necessary to grow those ventures, Black women in particular find their ventures stuck at the micro level. Among all businesses nationally, those owned by Black women have average sales per business of $28,000, compared to $768,000 for those owned by white men. And businesses owned by Black women have an average of 8.2 employees and average sales of $557,000, compared to 13.1 employees and $2,866,000 in average sales for those owned by white men.

Business establishments in the District of Columbia by sex and race (minority status)

These present inequities stem from the systematic denial of access to financial and social capital (among other factors) for women and people of color. The inclusion of social capital here may seem surprising at first; after all, we’re used to hearing, “It’s not personal, it’s business.” But personal relationships are vital to any business’s success, especially the success of new ventures. From getting an idea off the ground to connecting with customers, social capital is just as important as financial capital to a new business’s success. And for Black businesses in particular, especially those founded by Black women, many of the same barriers that have prevented equitable access to financial capital are at play in limiting access to social capital, resulting in a broken ecosystem.

I founded Black Girl Ventures (BGV), a D.C.-based social enterprise initiative, in order to increase access to capital for Black and Brown women. BGV’s work is centered around community inclusion in the entrepreneurial process. While our fellow ecosystem builders focus on traditional access to capital through reforming venture capital and banking practices, BGV supports these efforts through pitch competitions as vehicles for financial and social capital in the form of crowdfunded microgrants, coaching, and other resources.[3]

BGV Pitch is a pitch competition wherein the community donates and gets to vote on which business wins their donations—think Kickstarter meets Shark Tank. BGV pitch competitions draw inspiration from rent parties, the now-legendary parties thrown by Black residents in Harlem in the early and mid-1900s to meet the exorbitant rents charged by white landlords. More than just a party with a cover charge, these increasingly elaborate shindigs became a key part of the social fabric of Harlem, attended by poets and artists like Langston Hughes and with performances by musical greats such as Duke Ellington and Fats Waller. BGV draws from this tradition of community inclusion and creative innovation in order to help entrepreneurs access alternative sources of capital. In just two years, BGV has traveled to seven cities, funded 16 women, and drawn an event audience of over 5,000 people and an online audience of over 30,000.

Building social capital in communities of color allows more people to invest in founders and encourages entrepreneurs who may be struggling to grow their businesses. But even when funders, ecosystem builders, and other stakeholders understand that there are gaps in opportunities for entrepreneurs of color (especially Black women), the roots of lack of access to social and financial capital have gone somewhat unexplained.

Why social capital matters for achieving equitable access to financial capital

Access to capital—the ability to access money through avenues such as loans, grants, or outside investors—is vital for small businesses to succeed.[4] Small businesses often need access to relatively small amounts of funds in order to get off the ground, expand into a new market, or weather a short-term downturn in business.

Access to financial capital is also tied up with an entrepreneur’s social capital—personal relationships, an individual’s reputation, a level of trust that allows people to work together and take a risk. This may come as a surprise to many people, as they think of their own experiences applying for a credit card, mortgage, or student loan—relatively impersonal processes where the applicant fills out a form, and a lender makes a decision seemingly based solely on numbers on the page.[5] But we also know that these are not the only ways that people access capital. Intergenerational wealth and personal connections are always a hidden part of this process. Parents and grandparents often contribute to children’s education funds; family gifts, loans, and inheritances are also a major part of how many people make a down payment on a house.

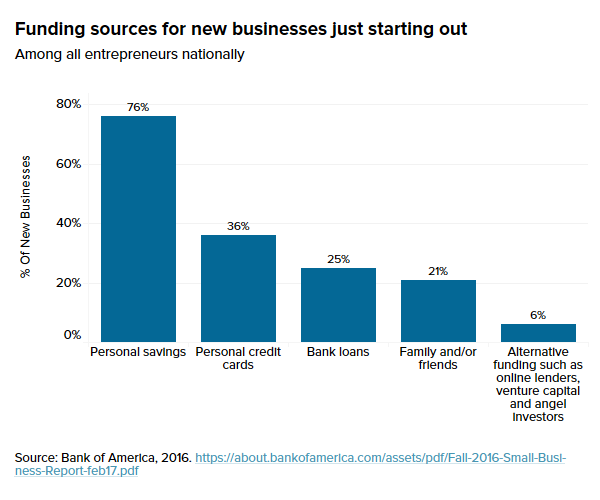

In business, too, social capital is vital for advancing a new venture from idea to reality. Many entrepreneurs’ first investors are family and friends: Bank of America has found that 38 percent of entrepreneurs have received a financial gift or loan from family or friends at some point to fund their business, and half (53 percent) say that family members serve important business roles.[6] As a business begins to expand and grow, venture capital and other sources of investment also depend on personal connections.

When we look deeper into entrepreneurs’ stories of success, we find that in the midst of all that inspiration and hard work, there are always a few key people that play a pivotal role in helping the business level up: Your first new customers may come from word of mouth. Your first loan comes from a friend of the family who admires your hustle. Your first big contract is from a second-degree connection of a former colleague. Founders will work hard and keep their head down to focus on building the best product, but the way for that work to find a wider audience is through relationships with people.

In 2015, I created a custom merchandise print shop and began printing my own t-shirt line as well as doing small runs for family reunions and small clothing brands. Through a friend of a friend, I was introduced to someone who was working in Supplier Diversity at Google. Getting large orders from Google double my annual revenue. A year later, I was approached by Amazon to create merchandise for their D.C. Amazon Web Services (AWS) conference—but I had no clue what to send over in a proposal. I consulted a friend who worked for a large corporation on how to approach Amazon. She gave me her tips, I included them in my proposal, and I was able to secure my first large contract and hire three people.

At every stage in this journey, my work was able to level up because of personal relationships. I met the person who would ultimately connect me with Google through a women’s group where I met women from a variety of backgrounds—and a variety of personal networks. Over time, that contact became a good friend and ally, and helped connect me with other people and opportunities. Other people at Google became strong supporters and champions of my work with Black Girl Ventures; Google Cloud for Startups has played a major role in our growth. With their sponsorship we were able to become a Google Charity, scale across the country with ease and hire local videographers and photographers in eight cities to help us tell our story. This increased visibility was a huge success factor that lead the Black Girl Ventures Foundation, our non-profit arm, to become a 2019 Kauffman Inclusion Open Grantee and being granted $450,000 from the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation to expand our work in five cities.

Unfortunately, this path to success is rare for Black founders, especially Black women, who have traditionally been locked out of the networks that would allow them to access necessary capital and opportunities. Within this broken entrepreneurial ecosystem, many of the same forces that prevent Black founders from accessing financial capital are tied into barriers to social capital. People of color have less household wealth to draw from—the racial wealth gap in the D.C. metropolitan area is particularly large—and rarely have a wealthy uncle or a college roommate whose dad is an investment banker. Across history, without sustainable ethical banking practices, ability to own land, ability to vote, the ability to sit at the same counter with a person who was not like them, Black people had to rely on each other, which meant relying on the limitations of their influence. For Black women entrepreneurs, they also experience the barriers that sexism creates, leading to additional disparities in opportunities and outcomes.

Why communities of color have lacked access to financial capital

The lack of access to financial capital for Black people in America is challenging to understand without insight into the timeline of available rights to fair and equitable access to finances through banks, land, and the ability to vote. The African-American journey “from being capital to becoming capitalists” has been plagued with segregation and systematic denial of access to fair wages, property, employment, bank accounts, and civil rights in general.

In the years before the Civil War and abolition, even free Black people faced many and shifting restrictions on their ability to access capital and accumulate wealth. Citing Dr. Letitia Woods Brown, Professor Christopher Klemek writes that “unparalleled opportunities for African Americans coexisted with draconian Black codes.”[7] After the Civil War, President Lincoln established the Freedman’s Bureau Act and the Freedmen’s Bank (headquartered in D.C.) to help newly-freed Americans navigate their financial lives. After President Lincoln’s assassination five weeks later, Mehrsa Baradaran writes in The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, President Andrew Johnson vetoed every initiative that could have given the Freedmen’s Bureau Act and related efforts any real impact. Active only between 1865 and 1874, the Freedmen’s Bureau ultimately was limited to providing accounts for savings and trusts, as opposed to being a commercial bank that could offer loans; however, with no federal banking oversight, the bank’s managers invested (and lost) the former slaves’ savings in speculation and fraudulent lending. The lack of access to financial resources also made it much more difficult for Black-owned businesses to weather financial shocks.

Despite the lack of government support, Black people created thriving communities across the country—but were always vulnerable to threats of racist violence. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, in the early 1900s, the city’s Greenwood District was known as Black Wall Street, “one of the most prosperous African-American communities in the United States.” In what became known as the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, Black Wall Street was burned down by a mob of white residents, sparked by an alleged sexual assault on a white woman by a Black man. Up to 300 residents were reported killed, and over 1,000 houses and almost all of the district’s businesses were destroyed.

Over the course of the 20th century, many other public and private actions further stripped Black people of wealth and economic influence, reducing their ability to access financial capital. For instance, redlining and racially restrictive covenants curtailed where Black families could purchase homes, a source of intergenerational wealth that today is a major source economic stability for white families in the U.S. Other Black families lost property, including farmland, that that they had owned since the Civil War. Today, these patterns inhibiting wealth-creation remain, with strong racial disparities continuing in conventional mortgage lending and algorithmic-driven online lending, and often continue regardless of income.

Finally, banks continue to show bias against Black entrepreneurs. A study using a “mystery shopper” approach found that banks are far more likely to offer help with small business loan applications to white entrepreneurs than to Black entrepreneurs. Banks also subject Black applicants to higher levels of scrutiny, such as by asking about their spouse’s employment status—a question not asked of the white applicants—or by asking for more detailed financial statements, even though the Black applicants in the investigation had stronger qualifications than the white applicants.[8]

How communities of color have been limited in their ability to build social capital

Financial capital is closely tied to social capital and social ties. And because social ties are based on personal relationships, it’s often difficult to think how they have been deeply affected by public and private policies. But social and economic segregation have both been the intention and the result of centuries of public and private practices in the U.S. Throughout the 20th century, Black people were restricted in where they could live and work, how they could travel, with whom they could socialize; their economic, educational, and wealth-building opportunities were restricted—and often destroyed—in ongoing attempts to limit their economic and political power.

Historically, Black communities—including Black entrepreneurs—have been separated from white communities, and not allowed to communicate. We have not been able to build that social capital. As a result, communities of color have not been allowed to access broader influential networks, which limits their ability to build and grow their businesses.

More than 50 years after the Fair Housing Act, Washington, D.C. remains highly segregated, the living result of past policies that constrained where and how Black residents could live and build wealth. Virtually all housing units that are most affordable to low-income families are located east of the Anacostia River, where Black residents make up over 90 percent of the population.[9]

Housing segregation—from racist landlords to redlining—not only limited wealth creation, but created and reinforced segregated patterns in where people live, where they work, where they socialize, and where their children attend school. Sometimes this exclusion included an entire municipality: Sundown towns were all-white areas where Black people were not allowed to be after dark, at the risk of violence. These patterns affect who residents have as neighbors, colleagues, classmates, as well as the weak ties—the second- and third-degree connections that are so crucial to entrepreneurs—they meet through those networks. According to Kyle Crowder, a University of Washington professor and co-author of a book on the cycle of segregation, “There are all kinds of forces that build residential segregation, but once it’s entrenched in a city, it tends to take on a life of its own and perpetuate itself over generations and generations.”

Outside of housing segregation, segregation in more public spheres interrupted our ability to travel, marry interracially, and occupy the same physical spaces, which inherently interrupts our ability to get to know each other and form connections that are crucial to building financial capital and economic success. True inclusion is required for our economy to function effectively.

In the workforce, Black workers were also denied opportunities to access the power of influential organizations and social networks, such as labor unions. Military service[10] and the entertainment industry provided Black men opportunities to travel and make new connections, although these opportunities were also shaped and constrained by racial segregation and sexist norms. For instance, even when Black jazz musicians were allowed (reluctantly) into traditionally white performance spaces, they returned to segregated hotels and traveled by segregated buses and trains. Even airport bathrooms were segregated.

During this time, Black women were further prevented in various and specific ways from accessing financial and social capital networks. Professor Robert Boyd writes that during the Great Depression, Black women faced particularly high rates of unemployment due to “the ‘double disadvantage’ of racism and sexism.” Black women turned to “survivalist entrepreneurship” out of necessity, which in northern cities took two main forms: keeping boarding houses, and training as beauticians and hairdressers. In southern cities, Boyd writes that Black women appear to have had fewer entrepreneurial alternatives, and were more likely to go into domestic service as their entrepreneurial pursuit. As a result, Black women were denied opportunities both because they had fewer work and education opportunities overall, and because when they did work they were often isolated from broader social networks through their roles in domestic work or their own home-based businesses.

What ecosystem builders can do

While slavery, the Great Depression, and Black Wall Street seem very far removed from where we are today, the Voting Rights Act is less than 60 years old. Just a few generations ago, almost everything that would usually create access to influential networks was illegal for Black people or they were segregated from the influential networks necessary to grow a business to the height of success available in America. And progress has come slowly. Today, Black entrepreneurs continue to have less economic stability to take a risk, fewer personal and family resources to draw from, and fewer high-income individuals in their personal networks to turn to for investments.

In response, ecosystem builders have launched a wave of new initiatives across the country to address the lack of access to financial capital for underrepresented founders. In D.C., Village Capital, Backstage Capital, Harlem Capital, and Precursor Ventures are just a few of the firms dedicated to investing in underrepresented founders, and Mayor Muriel Bowser recently announced the creation of the Inclusion Innovation fund in which D.C. government will partner with an investment firm to fund founders of color and the LGBTQ community.

Access to networks of experienced and wealthy people is the key to unlocking the financial divide in our country. But social capital is tricky; building connections in personal and professional networks will require intentional and inclusionary actions from businesses, investors, and others. So, what can ecosystem builders do to improve access to social and financial capital for Black and Brown women starting businesses in D.C.?

Find allies, not beneficiaries. Allies connect, collaborate, cooperate, coordinate, and champion. However, being an ally is not a top-down practice; it is a lateral concept that includes collaborating back and forth with empathy and education between various circles of influence.[11] And remember, if everyone around you thinks just like you, it will be challenging to progress your business to its full potential.[12] Innovation happens at the point of friction.

Reset your mindset on what success looks like. In technology spaces, Black people and other people of color—and especially Black women—also have to contend with what a good investment “looks like” (i.e., “anyone who looks like Mark Zuckerberg,” in the 2013 words of a venture capitalist). One way to tackle this specific type of unconscious bias is to expose yourself to new models of what success can look like. Put in the work to proactively escape your normal networks and genuinely connect with people who are not like you. Learn where people come from. Learn the history of another ethnic group or race. Listen to the lyrics of a different kind of music.

Know—and name—bias when you see it. You and your peers are in unique position to call each other to the carpet when you see subtle or overt forms of bias and discrimination. No matter where you sit in your organization’s hierarchy, you likely have some sphere of influence. How will you use it? Even—especially—in homogenous spheres of influence, there is tremendous power in one person who can be the voice of inclusion and change. And while you’re at it, think bigger: bring data and accountability systems into the process to find and address broader patterns in your organization, and lobby leadership for meaningful plans for change.

Don’t bridge the gap, raise the average. Part of the way that Black women and other people of color are shut out from networks and resources comes not only from low representation within sectors, but from investors’ insular social networks—in other words, the fact that they aren’t likely to connect with Black women who are working in these spaces. If the average number of women in the rooms you frequent are low, invite more women. If the average number of investments you’ve made are in a founder with the same racial, family, and educational background, be innovative and diversify your portfolio. Be open to seeing more than the usual suspects.[13]

Shelly Bell is a system disruptor and business strategist who moves ideas to profit while empowering people to live more authentically. Her organization, Black Girl Ventures (BGV) is a social enterprise that creates access to social and financial capital for Black/Brown women founders. A serial entrepreneur and computer scientist with a background in performance poetry, K-12 education, and IP Strategy, Shelly was named Entrepreneur of the Year by Technically DC and A Rising Brand Star by Adweek. She has been featured in Forbes, Politico Live, The Washington Business Journal, NewsOne, The Afro, and People of Color in Tech.

This publication is made possible with support from the Consumer Health Foundation (consumerhealthfdn.org/about) and the Meyer Foundation (meyerfoundation.org/about-us). It is part of a broader series of essays about racial equity in D.C., available at dcpolicycenter.org/racialequity.

Notes

[1] Nationally, over half (59 percent) of all Black-owned businesses are owned by women, but only 35 percent of Black-owned employer businesses are owned by women. Furthermore, women-owned Black businesses employ about 12 percent fewer employees than male-owned Black businesses on average. From Women’s Business Ownership: Data from the 2012 Survey of Business Owners, U.S. SBA, 2017.

[2] U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs, Characteristics of Businesses in the District of Columbia, 2016.

[3] For more on entrepreneurial ecosystems, see Daniel Isenberg, “What an Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Actually Is,” Harvard Business Review, 2014.

[4] This can also include other resources, like land or space to operate.

[5] These processes are certainly not free from discrimination and bias, but they are relatively formalized compared with other types of loans and investments.

[6] Owners of new businesses are especially likely to be receiving financial support from family and friends. (And 13 percent of small business owners say their family or spouse financially supports them with personal expenses such as buying groceries or clothing.)

[7] Christopher Klemek, “Exceptionalism and the national capital in late 20th-century Paris and Washington, DC,” in Capital Dilemma: Growth and Inequality in Washington, DC, edited by Derek Hyra and Sabiyha Prince, 2015, page 13.

[8] Note – this link has been updated (September 6, 2019). For more, see also “Shaping Small Business Lending Policy Through Matched-Pair Mystery Shopping,” published in the Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 2019.

[9] Data for Ward 7 and Ward 8 compiled by DC Health Matters.

[10] Georgetown Professor Maurice Jackson has written that the necessity of World War I created a major opportunity for Black men to connect with other Black men from across the country. Even though Black enlisted men were often treated unfairly—and certainly not always welcomed as heroes upon their return to the U.S.—their military service led to national and international travel and leadership experience, and forced a groundswell of social capital opportunities. For more, see “Music, Race, Desegregation and the Fight for Equality in the Nation’s Capital” in Capital Dilemma.

[11] A 2014 Kauffman Foundation study of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in St. Louis found that connections between entrepreneurs were “extremely valuable and weighty,” crucial to sharing knowledge and lessons learned.

[12] As the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City noted in its report Building Entrepreneurship Ecosystems in Communities of Color, “diverse networks provide better information sharing, faster change, greater ability to coordinate, and greater access to resources.”

[13] One study found that the likelihood that a woman would be hired from a hypothetical candidate pool increased from zero percent to 50 percent when the number of women in a four-person pool increased from one to two, with similar findings for candidates of color. For more, see Becky Strauss, “Battling Racial Discrimination in the Workplace,” D.C. Policy Center, 2019.