The pandemic-induced recession has put an unprecedented pressure on the District’s economy. Precautions taken to slow the spread of COVID-19 have closed businesses and schools, reduced travel and mobility, and put thousands out of work. With the dramatic decline in demand from consumers, and halted business operations, the nation swiftly fell into a recession at the end of February. By mid-July, thousands of District residents were unemployed, and 35 percent of residents aged 18+ predicted that their chances of paying rent were slim to none in the next month. While previous data show that projections on the ability to make rent and mortgage payments were more pessimistic than households’ actual track record, getting DC residents employment income again is imperative. As an urban employment center and a destination for workers, visitors, and businesses, the District has experienced dramatic losses in its workforce. While some have been insulated from the economic impacts, local economic activity has declined significantly, putting financial strains on businesses, households, and local government.

This is an excerpt of the 2020 State of Business Report: Pivoting from Pandemic to Recovery. Download the full report [PDF].

Acknowledgements

Washington, DC is a flourishing and diverse global city. Its leadership—including Mayor Muriel Bowser, the Council of the District of Columbia, and the DC Chamber of Commerce under the stewardship of Interim President and CEO Angela Franco—are the catalysts for the production of the 2020 State of Business Report: Pivoting from Pandemic to Recovery.

The Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, under the leadership of Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development John Falcicchio, and Sybongile Cook, Director of Business Development and Strategy, provided financial support for the production of this report.

Our thanks to photographers Ted Eytan, Bekah Richards, Kian McKellar, Joe Flood, and Aimee Custis for use of their photos throughout the report. Cover photo by Ted Eytan.

About this report

This report was prepared and produced by the D.C. Policy Center for the DC Chamber of Commerce. The D.C. Policy Center is an independent nonprofit think tank committed to advancing policies for a strong and vibrant economy in the District of Columbia.

The views expressed in this report should not be attributed to the members of the D.C. Policy Center’s Board of Directors or its funders. Funders do not determine research findings or the insights and recommendations of D.C. Policy Center employees and experts. Further information about the D.C. Policy Center is available at dcpolicycenter.org/about.

Executive Summary: Pivoting from Pandemic to Recovery

The pandemic-induced recession has put an unprecedented pressure on the District’s economy.

Precautions taken to slow the spread of COVID-19 have closed businesses and schools, reduced travel and mobility, and put thousands out of work. With the dramatic decline in demand from consumers, and halted business operations, the nation swiftly fell into a recession at the end of February. By mid-July, thousands of District residents were unemployed, and 35 percent of residents aged 18+ predicted that their chances of paying rent were slim to none in the next month. While previous data show that projections on the ability to make rent and mortgage payments were more pessimistic than households’ actual track record, getting DC residents employment income again is imperative. As an urban employment center and a destination for workers, visitors, and businesses, the District has experienced dramatic losses in its workforce. While some have been insulated from the economic impacts, local economic activity has declined significantly, putting financial strains on businesses, households, and local government.

The economic losses borne by residents and businesses are too great for the District government to cover alone. But the city’s policy actions can go a long way in mitigating risks to recovery. Yet, with its own finances at risk, the District will have to balance its budget while addressing as many social needs as it can. Recovery will be faster if fewer households experience the trauma of losing their homes, if fewer business owners carry the stigma of bankruptcy, and if workers can return to work without having to worry about their safety, health, or childcare needs.

Job losses from February to July of 2020 are three times the losses experienced during the Great Recession.

The COVID-19-induced recession has erased nearly seven years of private sector job growth in the District, eliminating 57,100 jobs. Between February 2020 and July 2020, private sector jobs declined from 564,200 to 506,700. Most of these job losses were felt in the leisure and hospitality sectors. Specifically, hotels and restaurants lost a combined 29,400 jobs, or almost half of the job loss in the District. As of the third week of July, 205,000 residents reported that they were not employed in the last seven days. Approximately 25 percent of this group were retired, sick, or disabled for a reason other than COVID-19; and 45 percent were out of work because they were laid off, furloughed, or their employer went out of business.

Job losses in DC have been greatest for middle- and low-income workers. Relative to January 2020 levels, 20 percent of workers making less than $110,000—the threshold for the top quartile of worker income—have lost their wage or salary income due to unemployment, lost hours, or furloughs. Accordingly, unemployment claims increased by over 10 times, from 7,000 claims in January 2020 to 75,000 in July 2020. Those claiming unemployment are disproportionately Latinx, young, and working in food, personal care, and service industries. Additionally, those who have lost jobs are disproportionately women and people with children under the age of 18 in the household.

While the District reversed some of the deeper job losses experienced in April and May, a rapid recovery is unlikely. Job postings have not yet recovered. By the end of August, advertisements for jobs that do not require experience or credentialing were approximately half as prevalent as before the pandemic began, and high-skill job postings had been reduced by 25 percent.

The high level of unemployment is also putting a strain on the District’s unemployment insurance program. The District started 2020 with a robust balance of $515 million in its Unemployment Insurance Trust Fund. Historically high levels of claims have exhausted more than half of this balance. In June and July of 2020, the city paid out five times in benefit payments compared to the tax revenue it collects from employers. The strong fund balance has allowed the city to buy some time, but if current trends continue, the demands on the unemployment insurance program could far exceed what the city can support by the tax increases allowable under the current program design.

Finding new workers when recovery begins is among the top concerns of small businesses in the District. One disconcerting trend is the increased number of discouraged workers who have stopped searching for work. At the time of this report, the labor force in the District has been reduced by 32,000 residents. Of these residents who have left the labor force, many cited the need to take care of children or elderly people, and concerns over contracting or spreading COVID-19. Others became discouraged because they thought they would not be able to find a job.

Policies that enhance the safety of workers, as well as supports for childcare and care for the elderly, would help District residents return to work. The District has had a good start, offering clear guidelines to different types of businesses about what they must do to minimize the risk of transmission.

Frequently Used Terms in this Report

DC workforce

All persons actively working in businesses located in the District of Columbia, regardless of where they live.

Discouraged worker

A person who is eligible for employment and can work but is currently unemployed and has not attempted to find employment in the last four weeks.

Economic recession

A significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real Gross Domestic Product (GDP), real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.1 Officially defined as a fall in GDP in two successive quarters.

High-propensity business applications

Business applications that have a high propensity of turning into businesses with payroll.2

Labor force

All DC residents over the age of 16 who are either employed regardless of where they work, or unemployed and actively seeking work.

Non-withholding taxes

Part of personal income taxes collected from quarterly estimated payments made by individuals. These taxes are largely a reflection of dividends and rents earned by individuals and proprietors but are also sensitive to stock market performance.

Unemployment rate

The number of people in the labor force who are not employed and are actively looking for work.

Withholding taxes

Part of personal income taxes collected from businesses at the time of payroll.

Small businesses are bearing the brunt of the costs of the pandemic.

Small businesses are vital to the employment of District residents and attractiveness of the city. Due to pandemic-related concerns and constraints, many businesses in the District have closed their doors and lost revenue: 28 percent of the District’s small businesses were closed as of July 2020, and small business revenue was down by approximately 50 percent. And 80 percent of small businesses note that they have experienced negative impacts—a combination of reduced operations and revenue—since the pandemic. The District’s small businesses have seen the third largest negative impact and sixth largest closure rate of 53 major cities in the United States.

A larger share of small businesses now believe, compared to at the beginning of the pandemic, that they will not be able to return to normal operating capacity for at least six months or more. They cite the need to raise revenue and market their services more effectively as their most important concerns. They also need help to pivot their operations to adapt to the new normal, which includes developing more of an online presence to advertise their services and deliver services directly to customers—on or off premises.

The pandemic has changed the business revenue structure by increasing costs for the foreseeable future. Businesses need to take extensive precautions to limit the spread of disease. This means higher costs associated with purchasing Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and cleaning and sanitizing efforts. They will also have to increase their capacity to monitor their employees to ensure that workers who show up to work are healthy. These businesses will be more likely to stay open—or stay in the District—if they are supported by policies that help them expand their operating capacity and sales and reduce the costs associated with complying with pandemic-related regulation.

While many businesses are closed and losing revenue, entrepreneurial activity has not decreased. Between July and mid-August 2020, the number of business applications were 40 percent higher than the same period last year. This includes “high propensity applications,” which are more likely to turn into wage-paying businesses in the next year.

The projected revenue loss for the city is far greater than what the city experienced in its recent history.

While the pandemic-induced recession has increased the need for public supports, the decline in economic activity in the city is also testing the fiscal resiliency of the DC government. District officials reduced the estimated revenue for fiscal years 2020 and 2021 by $722 million and $774 million, respectively, compared to December 2019 projections. These revisions are far deeper and longer lasting than any revenue loss the city has experienced since the Revitalization Act, including the period after the 9-11 attacks and throughout the Great Recession.

The most immediate impact of the pandemic-induced economic slowdown has been on sales taxes. Half of sales tax revenue in the District is generated by hotels, restaurants, and arts and entertainment venues. It is projected that sales taxes will decline by 22 percent in fiscal year 2020, totaling $342 million. If there is continued depressed activity, or a second

wave of COVID-19 infections causing additional shutdowns, revenue could be further depressed.

Losses experienced in 2020 are projected to reduce personal and business franchise tax collections through 2021. So far in 2020, withholding taxes have been held steady at levels similar to 2019, but non-withholding taxes are lower, reflecting the weaknesses in the stock market and perceived risks about future earnings. Real estate taxes are projected to remain stable through 2021, but this is a feature of the administrative process, which values income-generating buildings based on the income and expense statements from two years prior. However, if COVID-19 discourages leasing activity, increases vacancy, or otherwise reduces rent payments from commercial leaseholders, a larger number of landlords—compared to the usual level—will likely appeal their tax assessments, and this can potentially reduce tax revenue in the future.

With so much unknown about the future of the economy, increasing taxes to meet the needs of residents and businesses in the city will add to fiscal risks.

Local policy will matter in shaping recovery and building resiliency.

While the District government alone cannot make up for the economic losses incurred as a result of the pandemic-induced economic recession, it can adopt the right policies to shape and strengthen economic recovery even under adverse conditions.

To support business resiliency and preserve entrepreneurial capacity, the District can help create conditions which will allow businesses to continue to operate and expand sales and revenue. These include:

- Provide expanded and subsidized supply of PPE to businesses to help reduce the risk of transmission between workers

and customers. - Develop rules around access to public space, especially outdoor spaces, to conduct business, and support investments in power infrastructure and equipment such was outdoor heaters to help businesses operate successfully and safely through the cooler fall months.

- Reduce permitting costs and simplify procedures, possibly deferring permit costs, for example, to sustain existing businesses and foster the creation of new businesses.

- Review regulatory restrictions on business operations and professional licensing, especially if regulations interfere with virtual provision or services or off-premise services.

- Provide additional technical assistance and consultations to help navigate the new regulatory landscape.

- Support continuing education for small business owners to assist with the challenges of maintaining a productive workforce, such as the transition to online sales, legal advice, or assistance with PPP loan compliance.

Businesses are also concerned about finding workers when it is time to reopen or expand operations. To support return to work, the District can:

- Consider transportation interventions that are safe alternatives to crowded public transit.

- Invest in programs to close the digital divide and support individuals and small business owners in obtaining the necessary technology to be able to work productively from home.

- Provide operational support for childcare centers to cover the increased costs of sanitation and the decrease in revenue due to new staffing restrictions.

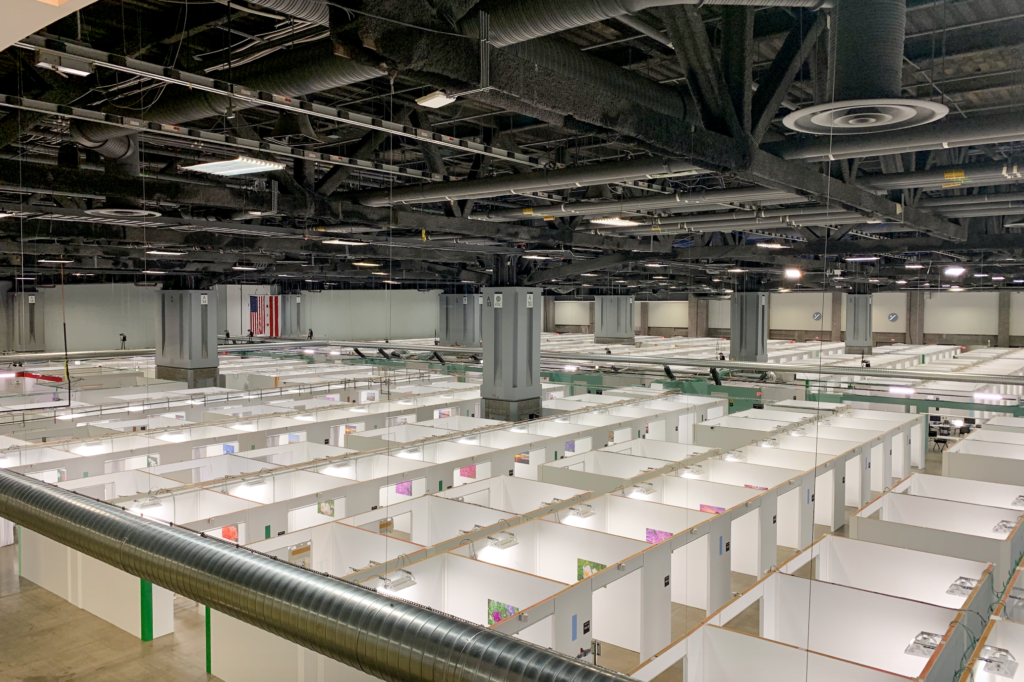

- Consider temporary changes to zoning laws to allow for alternative uses of underused spaces.

- Provide parking subsidies for essential workers who are wary of taking public transportation.

The District was able to maintain its spending and preserve all its workforce by using the city’s substantial savings. However, if the period of economic activity remains depressed beyond the revenue projections, difficult decisions may have to be made. To maintain the fiscal health and resiliency of the city, the District can:

- Conduct a comprehensive expenditure review of DC government finances in anticipation of a future with tighter revenue.

- Identify programs and expenditures that could be put on hold to divert funds to interventions related to the COVID-19 response.

- Consider the economic impact of all new policies, not just the fiscal impact, to ensure that the city’s long-term competitiveness is preserved.

- Consider alternatives to the current unemployment insurance tax structure that balances benefits with the additional costs of raising taxes on businesses.

Introduction

The first case of COVID-19 in the District of Columbia was confirmed on March 7, 2020. During the weeks that followed, life in the nation’s capital changed dramatically.

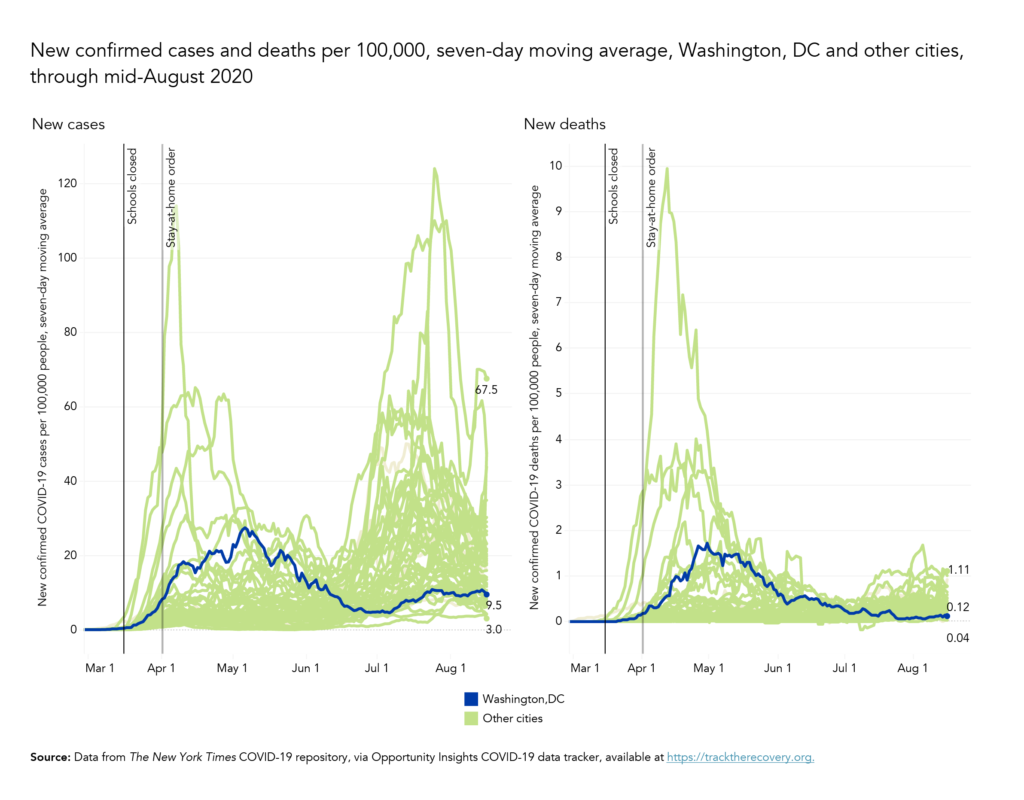

Schools were closed and restaurants and bars suspended in-house dining on March 16. Mayor Muriel Bowser issued a “stay at home” order, effective April 1, 2020.3 By this time, many businesses had already closed their doors and sent employees home. Still, both the number of cases and the death rate in the District continued growing through May. Since then, new case growth has stabilized, and the death rate has gone down significantly. By mid-August, with fewer than 10 cases per 100,000 persons per day, and approximately one death every other day, the District has been more successful in containing COVID-19 than many other cities in the country (Figure 1).

Business closures and stay-at-home orders across the country have been necessary to control the spread of the disease, but they have also come at a high economic price. In June, the National Bureau of Economic Research—the official reporter of business cycles—announced that the U.S. had entered a recession at the end of February. This deep and swift recession has exacted a heavy toll on the District’s businesses, workers, residents, and government finances.The 2020 State of Business Report: Pivoting from Pandemic to Recovery takes stock of the impact of the COVID-19-induced recession on the District. It compiles data from the first five months of the recession, February through July 2020, to present how profound the impacts have been on the city. The report covers areas pertinent to the District’s economic viability: consumer demand and spending; businesses capacity to operate and generate revenue; employment, unemployment, and hiring trends; impacts on households; impacts on tax revenue; and expectations about the future of the city.

The report also reviews short-term and long-term risks brought about by COVID-19 that can jeopardize DC’s economic recovery and amplify inequities in the city. In March, the expectation was that within a few months there would be a return to normalcy. Many businesses surveyed at that time expected that by the fall, the disease would be under control, and by the beginning of 2021, it would have largely passed.4 However, uncertainty about the country’s ability to contain the disease has increased since March. This uncertainty imposes additional risks to the District’s economy, which is heavily dependent on the presence of workers and tourists, and street-level activity.

In the short run, prolonged closures can have a chilling impact on entrepreneurial activity. The District has seen a tremendous number of new business starts in the last 20 years due to a confluence of many positive factors: a growing population, increasing incomes, favorable financial conditions, and improved city services. But, if closed by the pandemic, many businesses will take a long time to rebuild themselves if they can rebuild at all.5 Rebuilding a productive team of employees will be more difficult for those businesses that have had to lay off many employees. Future financing could be more difficult if a business had to default on a loan or failed to pay back credit extended by vendors.6 For example, half of the restaurants that temporarily closed their doors on March 16 are not expected to open ever again.7 Most retail stores in downtown DC reopened in July, but the sales volume was at 30 to 50 percent of 2019.8 The impacts will spread to households, especially to middle- and lower-income households whose members are employed by small businesses. As of July 21, 2020, 37 percent of DC households have reported income losses associated with COVID-19, and 23 percent of adults reported missing last month’s rent or mortgage payment, or did not think that they could make next month’s rent or mortgage payment on time.9 While households can weather a few months of unemployment, recovering from losing housing is far more difficult.

In the long run, the pandemic can alter the attractiveness of the District to businesses, workers, and residents. The 2019 State of Business Report: Building a Competitive City10 indicated that the qualitative advantages that made the District attractive had largely overshadowed its comparatively higher cost of living and doing business. Despite higher housing and childcare costs, higher commercial rents, higher taxes, and, for some, longer commutes; residents, workers, and businesses have gladly chosen DC as their home to benefit from the high quality of life, availability of amenities, and concentration of businesses that provide a strong labor market and robust commercial activity. COVID-19 can change this calculus.

For example, half the workers in the Washington metropolitan area can work from home—the third highest share among all metropolitan areas in the nation.11 Accordingly, many companies in the region as well as the federal government have indefinitely allowed their workers to work from home. Telework is providing some protection to District businesses and workers through the pandemic, but it could also mean that workers can work for a District establishment without setting foot in the city for long periods of time. There is increasing evidence that many companies will continue with telework, which is both popular among workers and has significant cost-cutting implications for businesses.12 If worker location ceases to be important, then, when recovery begins, business location will also matter less in attracting a talented workforce. We are already seeing signs of reduced demand for office space and commercial real estate. There is also increasing evidence that suburbs are outperforming central cities in home sales.13 If these trends hold, they pose a significant risk to the District’s fiscal capacity, as a substantial amount of revenue is driven by commuter activity14 and the demand for real estate in the city.

While the economic losses of COVID-19 borne by residents and businesses are far too great for the District government to cover, the city’s policy actions will greatly affect how it recovers. With its own finances at great risk, the District will have to find a way to keep its financial house in order while addressing as many social needs as it can. Recovery will be faster if fewer households experience the trauma of losing their homes, if fewer business owners carry the stigma of bankruptcy, and if workers can return to work without having to worry about their safety, health, or childcare needs. Businesses will also be more likely to stay in the District if they are supported by policies that decrease the costs of and risk related to doing business, such as high taxes, high real estate costs, and regulatory interventions, and if they expect that their consumer base will remain strong.

This is an excerpt of the 2020 State of Business Report: Pivoting from Pandemic to Recovery. Download the full report [PDF].