On Wednesday, February 16, 2022, Education Policy Initiative Director Chelsea Coffin testified before the D.C. State Board of Education, on the importance of collecting data that can help track the education system’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. You can read her testimony below, or download a copy.

Good evening, members of the DC State Board of Education (SBOE). My name is Chelsea Coffin and I am the Director of the Education Policy Initiative at the D.C. Policy Center, an independent think tank focused on advancing policies for a growing and vibrant economy in D.C. Tonight, I am previewing some of our findings from State of D.C. Schools, 2020-21 that will be published on March 10. I will share what they may mean for the budget and recovery, especially for students designated as at-risk, and how the city must invest in collecting information that can help track recovery.

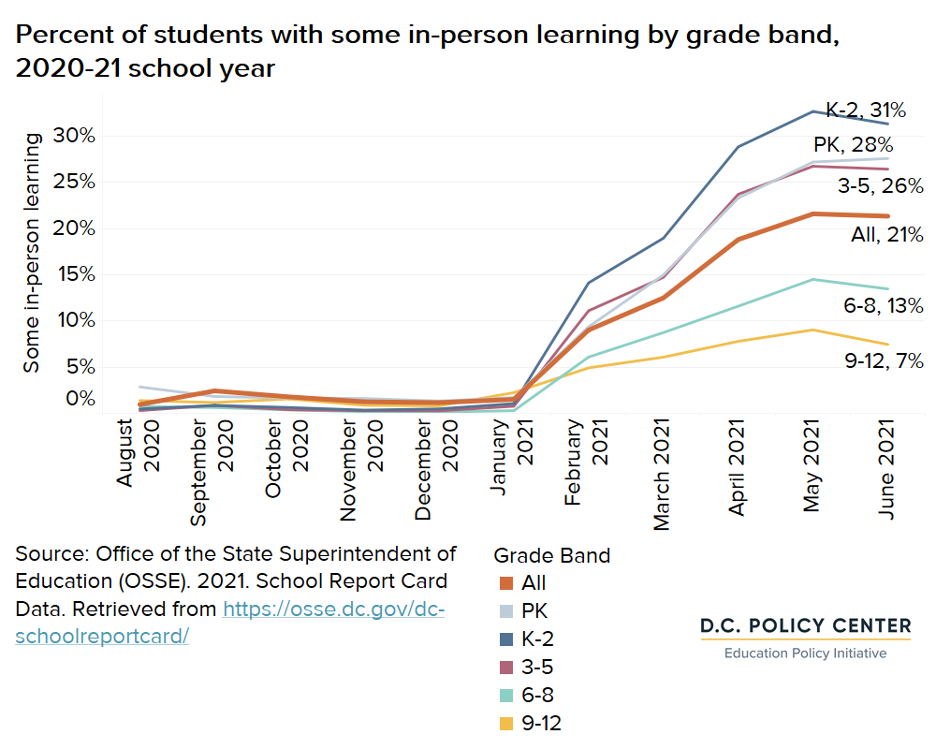

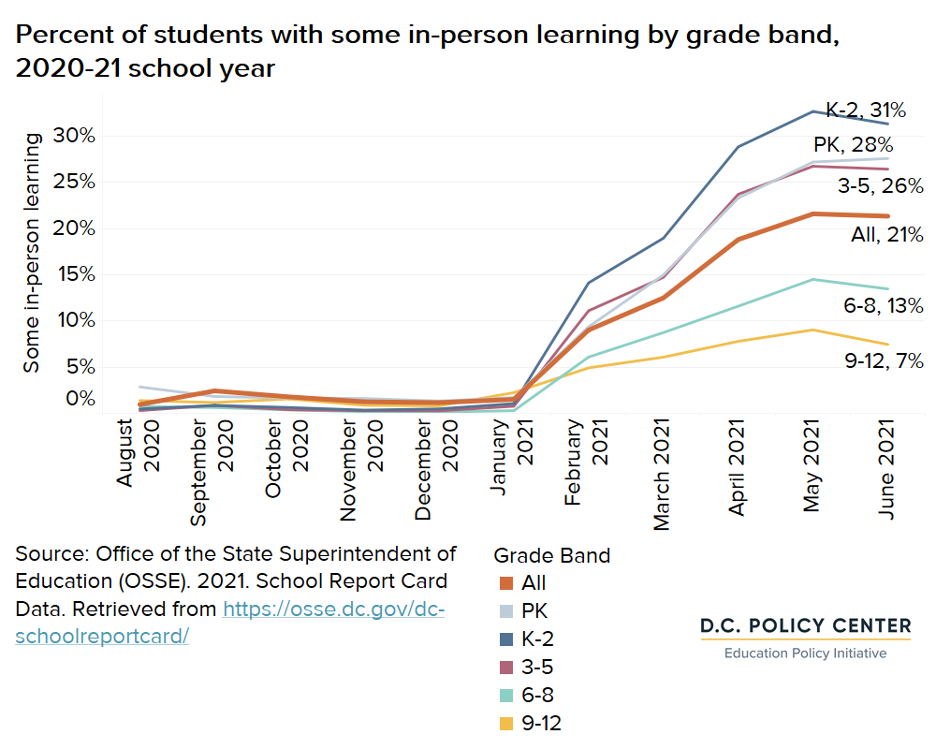

The State of D.C. Schools report walks through the full year of learning during the pandemic, which was incredibly challenging for students, teachers, and parents. One of the biggest changes in school year 2020-21 was that there was likely less instructional time and less content covered. At the start of the school year, 99 percent of students were learning virtually for five days a week (many with one day of asynchronous learning), and 79 percent of students were still doing so by the year’s end. The remaining 21 percent who did return to in-person learning were more likely to be younger students, and to go to school in the city’s more affluent wards and likely attended in-person for no more than three days a week. Along with changes in instructional time, less content was taught – two-thirds of LEAs reported that they scaled back on standards after the spring of 2020 and in light of the continuing pandemic.

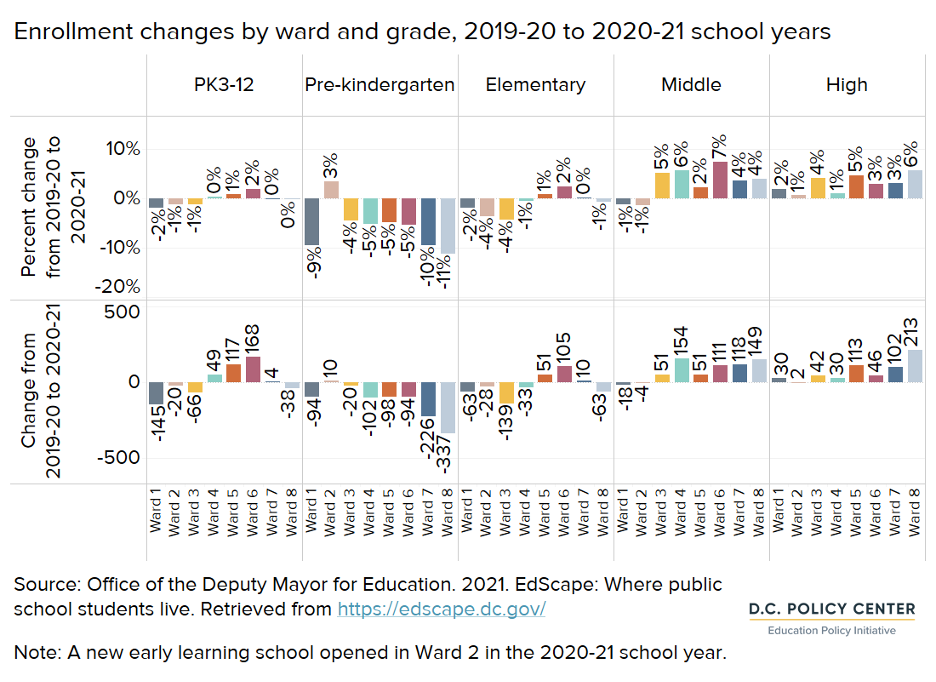

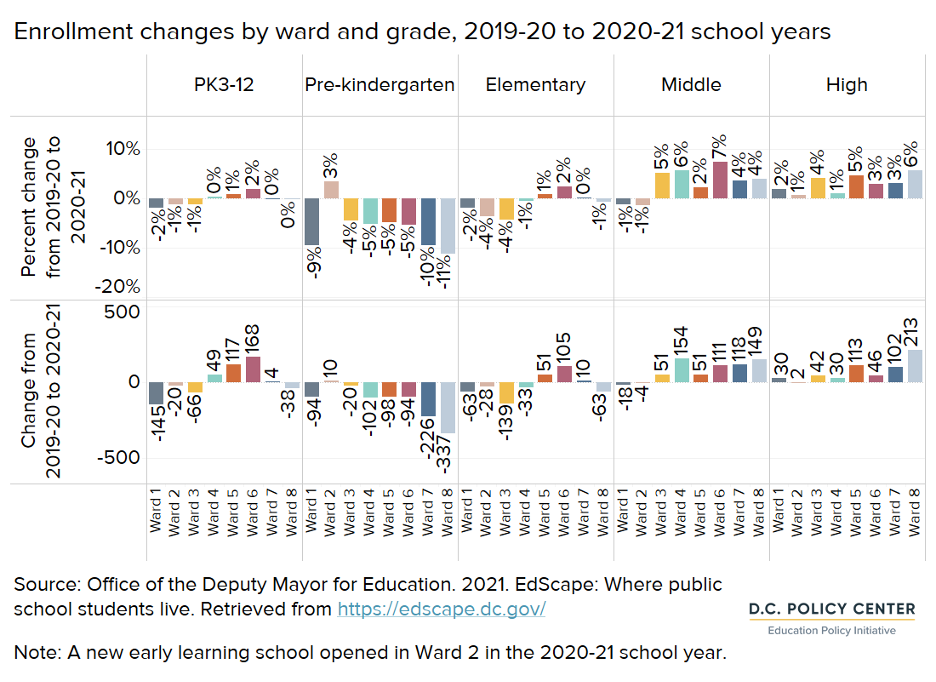

In addition to less instructional time and content, there were fewer students enrolled than expected in school year 2020-21. Although systemwide enrollment across pre-kindergarten to grade 12 was projected to increase by 4,000 students in 2020-21,1 it only increased by 17 students. Enrollment in the usually highly-demand pre-kindergarten grades declined for the first time by 7 percent (942 students), showing that D.C. parents opted out of what could be a challenging virtual learning environment for young students – especially in Wards 7 and 8. Enrollment in D.C.’s 14 adult and alternative schools also dropped sharply, by 13 percent or nearly 950 students, between 2019-20 and 2020-21. These lower levels of enrollment in noncompulsory grades will have ripple effects in the years to come.

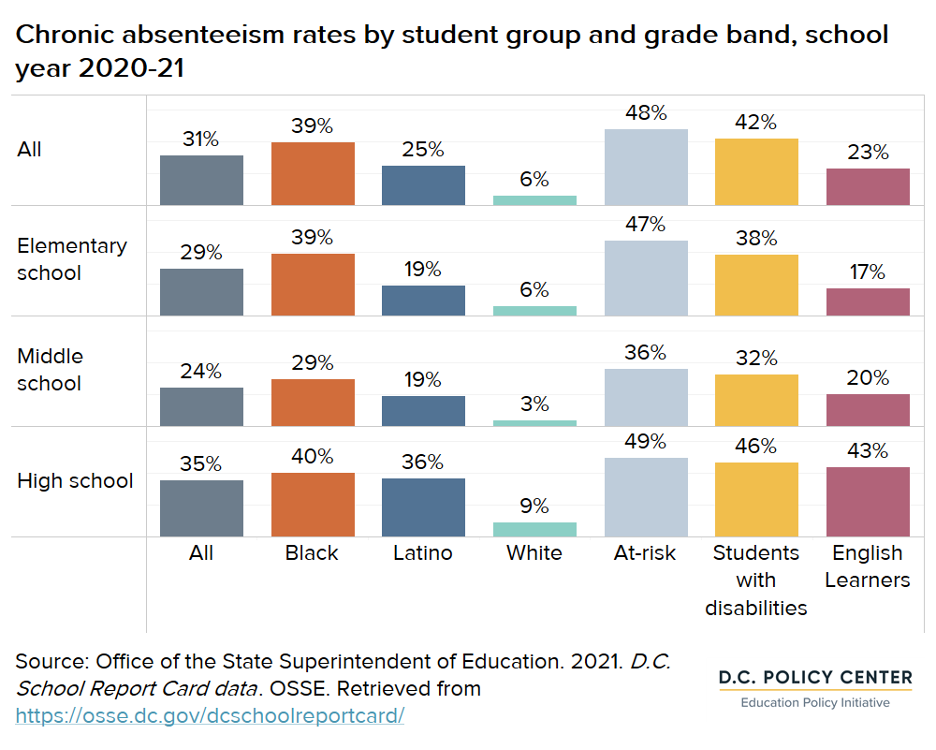

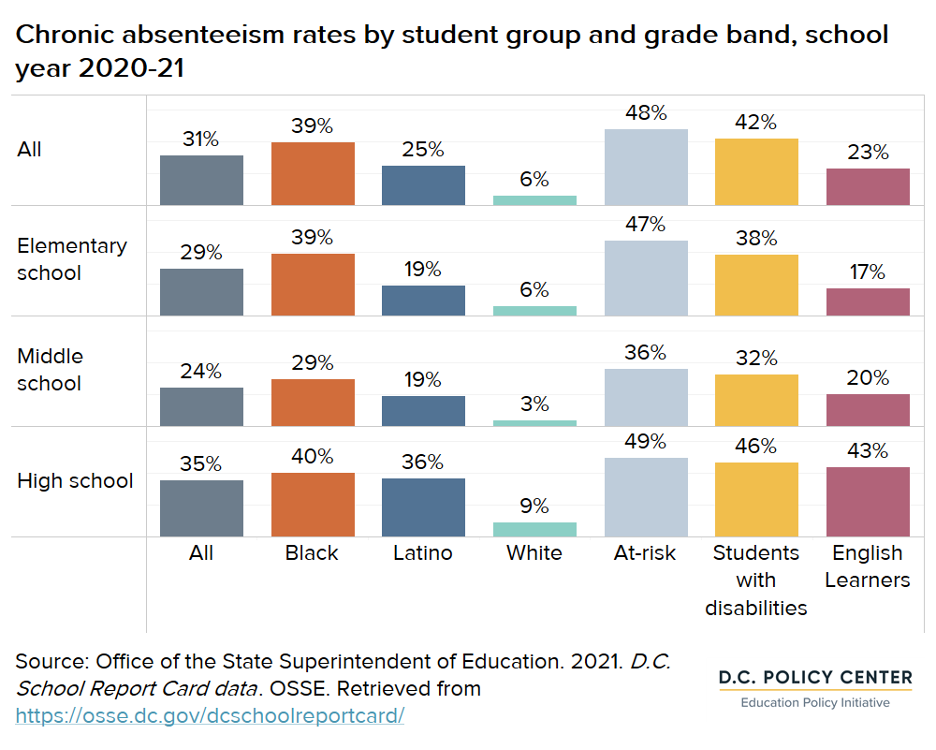

During last school year, early signs point to lower levels of engagement, unfinished learning, and wellbeing issues. Even though D.C. relaxed in-seat attendance requirements, 31 percent of students were chronically absent, missing 10 percent or more of the school year. Pre-kindergarten students attended school an average of eight out of every 10 days. In absence of the statewide assessment, an EmpowerK12 analysis of school-level assessments shows that academic performance of schools declined during school year 2020-21. In addition, there was more unfinished learning for students with disabilities and English learners. On mental health, there is little data on how often students needed or received mental health services, but qualitative data and focus group conversations paint a mixed picture and show that many students experienced increased isolation, anxiety around COVID-19, and general stress of virtual learning.

The year of school during the pandemic often had disparate impacts for student groups, especially – and relevant to the budget—for students designated as at-risk. First, there was an increase in the percentage of students designated as at-risk to 45 percent compared to 43 percent in the previous year. For a variety of reasons, some related to the challenges of virtual learning and adequate technology access, students designated as at-risk were less likely to engage in school: compared to all students, they were 1.5 times more likely to be chronically absent and they missed an extra half day of pre-kindergarten a week. They also experienced a 27 percentage-point decrease in reading on grade level, twice as much as their not-at-risk peers.

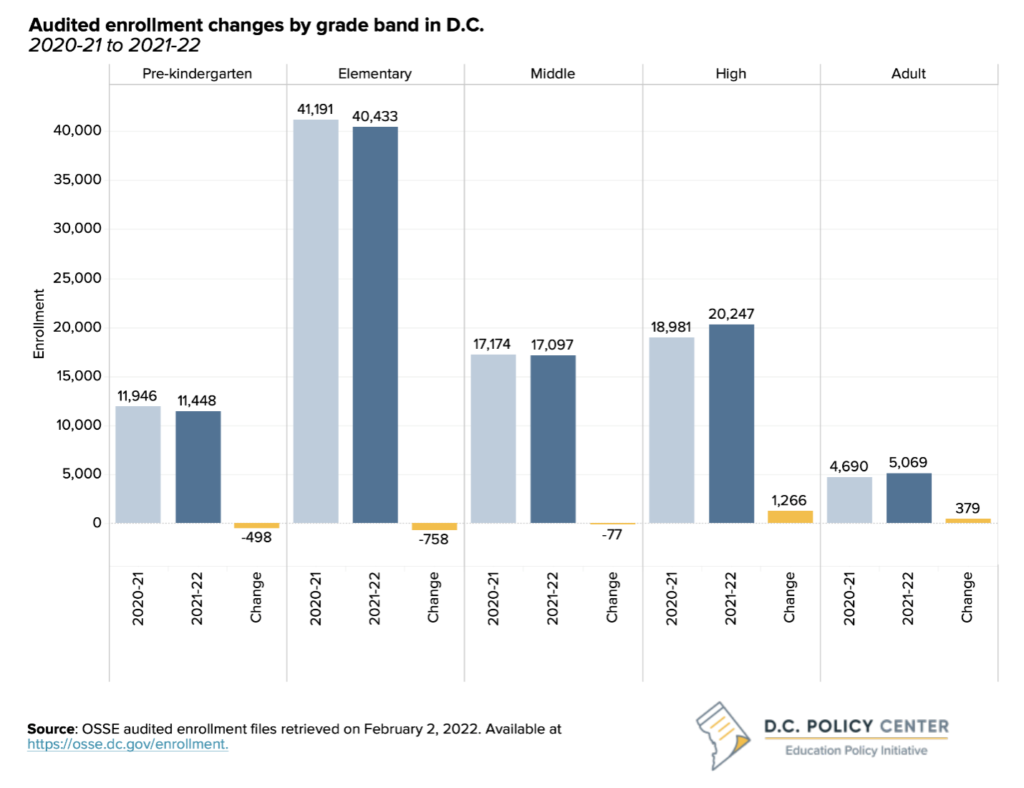

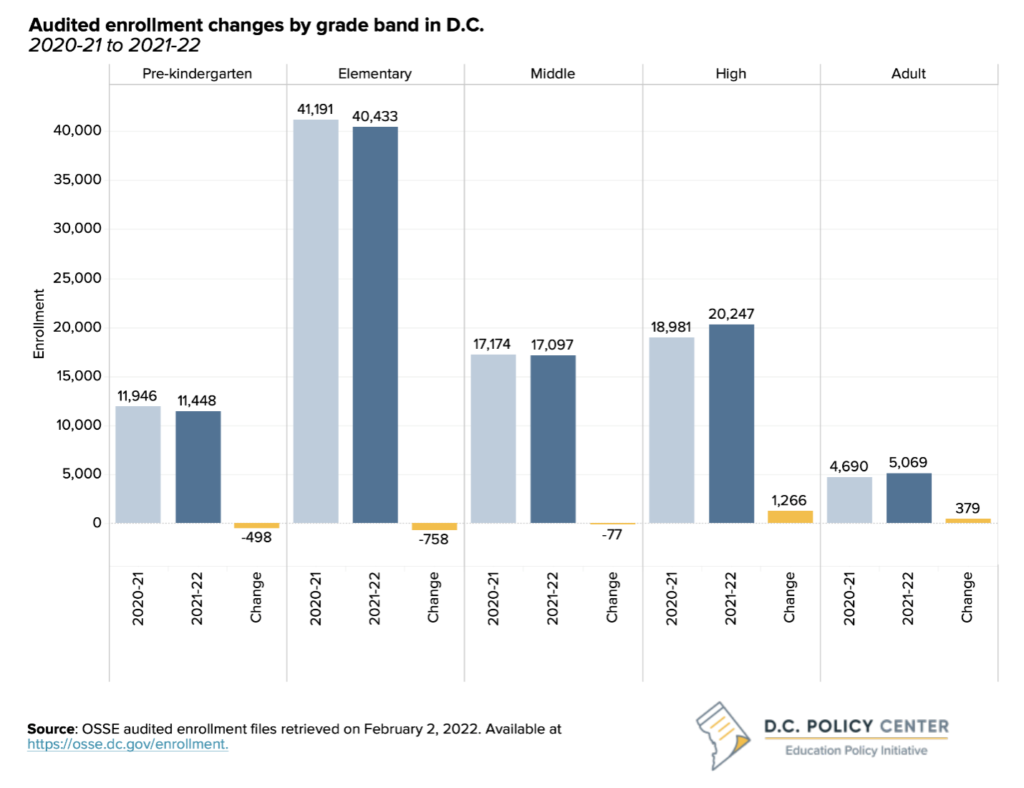

While the previous school year introduced challenges, we don’t know much about how students are recovering during the 2021-22 school year. Schools are open again in-person aside from quarantine time — an estimated 1.3 percent of DCPS students and 2.7 percent of DCPS teachers were in quarantine on a given day in the fall 2021. Enrollment is almost the same as last year, but remains down for pre-kindergarten and elementary grades. But it is likely that academic and wellbeing recovery is going to be a multi-year process, and D.C. needs a clear plan in education that focuses on student academic success and supports for students, and takes stock of community factors that influence students’ ability to fully engage in school.

In this budget cycle, the UPSFF increase of 5.9 percent and the multiyear investment of $27 million for school-based mental health supports are a strong start toward recovery. However, this is the time for a big statement to target resources where they are needed most for students designated as at-risk. We don’t yet know the weight for students designated as at-risk, but last year’s weight of 0.24 remained well below the 0.37 weight recommended in the Adequacy Study. This means that students designated as at-risk are receiving less in per pupil funding from local resources than they need, and that they could benefit from more resources to recover from the academic and socio-emotional impact of COVID-19. In addition to completing learning assessments, D.C. should consider regular systemwide surveys of students, parents, and teachers to take the temperature on issues like trust in schools, job satisfaction, wellbeing, and others.

Thank you for your time. We need to focus on equitable recovery, and invest in collecting information that can help track these outcomes. I am happy to answer any questions you may have.

Endnotes

- Government of the District of Columbia. 2020. “Fiscal Year 2021 Approved Budget and Financial Plan.” Retrieved from: https://cfo.dc.gov/page/annual-operating-budget-and-capital-plan