Individuals with trauma responses can face great difficulties in finding and retaining a job. Trauma responses oftentimes make it difficult for workers to handle everyday stressors at work. While many publicly-funded job training programs have adopted a trauma-informed approach, it is rare to find private employers who have adopted trauma-informed management practices as these changes are often considered difficult and outside of the scope of management.

This report explores three topics related to the impact of trauma in the workplace: (a) what we know about the impact of trauma on employee success, (b) what role policy and public programs can play in strengthening supports to maximize the success of employees with trauma responses, and (c) what employers can do to support employees who have trauma responses.

The report is centered around a case study of Turnaround, Inc.—a nonprofit founded in 2015 with the mission of providing permanent, skilled-trade employment to individuals with high barriers to employment. Turnaround, Inc.’s Work Empowerment Program trained and employed adults from Wards 7 and 8, referred by social service and case management agencies in the public and private sectors. The program was operational for four years between March 2017 and January 2021, when it was paused for an assessment and impact evaluation.

Quick links

Acknowledgements

The D.C. Policy Center thanks Gabrielle Cesar-McBride, the Executive Director of Turnaround Inc. for the information she provided for this research. All information on Turnaround and case notes from program participants presented in this report are based on this information. Our gratitude goes to Shanaqua Blake, Kelly DeCurtis, and Kenya Harris for their time and important insights. We thank Meika Wick, Michelle Palmer, Jennie Niles, Erin Bibo, Kevin Clinton, and Patty Brosmer for comments and suggestions on earlier drafts.

We are grateful to Thomas Gallagher for financially supporting this work.

INTRODUCTION

The need for trauma-informed management practices

Each year, the District of Columbia, along with the federal government, invests millions of dollars in supporting District residents who need help finding a job. The District invests in job readiness, job training, career counseling, and job placement programs run by government and private agencies or offered by adult charter schools. According to the Workforce Development System Expenditure Guide published by the DC Workforce Investment Council (WIC), in Fiscal Year 2021, for example, the city spent $100.5 million (budgeted from a mix of local and federal dollars) to support 59 different workforce programs and 199 separate activities across 16 different government agencies1 that collectively served D.C. residents over 57,800 times.2,3 While the D.C. government publishes some data on program completion rates, little information exists on the long-term career outcomes of the program participants. The limited data compiled in the WIC reports suggest that many adults who participate and complete publicly-funded workforce programs have difficulty getting and retaining a job.4

Similarly, employers spend a tremendous amount of time and resources to fill positions that open because of turnover. Each month, two to three percent of employees turn over in the Washington metropolitan area.5 Some of this turnover is expected, tracking the normal expansion or contraction of employment in business establishments or the result of typical job mobility for workers. But turnover is particularly high in some industries, reflecting deeper challenges in finding and keeping employees. For example, between 2010 and 2019, annual employee turnover among housing providers hovered around 33 percent, with nearly 40 percent of onsite maintenance staff turning over each year.6 For D.C. employers, the estimated cost of replacing these workers is approximately $37 million.7 Turnover rates at hotels and restaurants could be as high as 70 percent8 and it could cost D.C. employers more than $130 million a year to replace them.9 In construction, the turnover rate in the third quarter of 2021 hovered around 26 percent10 compared to the long-term average of 18 percent, and the estimated cost of replacing these workers is $77 million.11

While the reasons for the low rates of job placement and retention are many, in this report, we focus on one aspect: the role of trauma as a barrier to obtaining and keeping a job. Trauma is defined in this report as a response to an event (or a series of events) that invokes unpredictable and negative emotions such as fear, helplessness, or horror associated with past experiences.12 Trauma can manifest itself in the workplace in many ways such as strained relationships or physical, emotional, psychological, or behavioral reactions. Trauma responses can make it difficult to work through common workplace stressors—such as making a mistake or having a disagreement with a client or colleagues—and can cause unexpected reactions and behaviors that fall outside the expected realm of professional etiquette.13

Research shows that many low-income adults accessing publicly-funded employment services experience trauma responses, affecting their ability to thrive in a work environment.14 Interviews with stakeholders in D.C. show that many of the city’s workforce programs have begun to adopt trauma-informed practices in their service models. But even when individuals successfully complete job readiness programs and find employment, trauma could remain as a barrier to employee retention. Employers and managers are not always ready interact with, show empathy toward, or understand common problems that can arise with employees experiencing trauma responses. Employees, too, must be prepared to adapt to or cope with the stresses of the workplace through learned strategies for handling workplace stressors. Without intentional trauma-informed practices adopted by all three—the public sector which invests in preparing workers, employers who hire graduates of publicly-funded workforce programs, and workers themselves—the full value of investments made in workforce readiness will likely go unrealized.

This report explores three topics related to the impact of trauma in the workplace: (a) what we know about the impact of trauma on employee success; (b) what role policy and public programs can play in strengthening supports to maximize the success of employees with trauma responses; and (c) what employers can do to support employees who have trauma responses. The report is centered around a case study of Turnaround, Inc.—a nonprofit founded in 2015 with the mission of providing permanent, skilled-trade employment to individuals with high barriers to employment. Turnaround, Inc.’s Work Empowerment Program worked with adults from Wards 7 and 8, referred by social service and case management agencies in the public and private sectors to train and employ them. The program was operational for four years between March 2017 and January 2021, when it was paused for an assessment and impact evaluation.

The case study on Turnaround, Inc. is important because it is one of the very few examples of how a trauma-informed workplace might operate. While there is consensus that trauma-informed practices in the workplace can increase professional success,15 little knowledge exists on the types of modifications needed to adopt such practices. The Turnaround Inc. experience shows that the language and practices in a trauma-informed workplace practices could be at odds with what managers have come to accept as standards of professional behavior.16 The case study also shows that it could take an exceptional amount of work on part of managers to shift focus from certain worker behaviors to strategies for improving worker success and do so while staying operational.17 As such, Turnaround Inc.’s operations, experiences, and outcomes provide important insight as to what it may take to implement trauma-informed management practices, what can be expected from employers when working with workers who have trauma responses, and how the government and employers could collaborate to improve the life outcomes for these individuals.

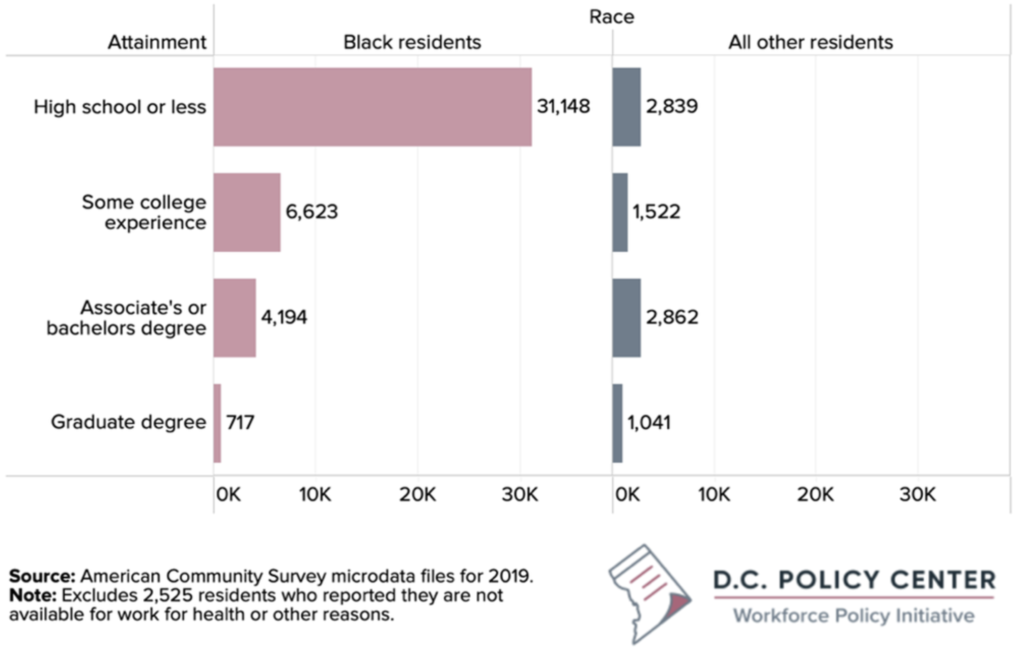

This topic is particularly relevant to the District of Columbia because some of the disparities in employment and life outcomes between the city’s residents are likely related to trauma. In 2019, of the 415,828 D.C. residents between the ages of 17 and 64 (excluding those who were in school), 53,471 (13 percent) were not working.18 Three quarters of these non-working adults were Black residents without college credentials. While we do not have data on how many of these adults have trauma responses, indirect data on mental health indicators suggest that this incidence is high: The same year, 11.5 percent of adults 18 to 65 who live in the District reported having more than 14 days of poor mental health in the previous month (compared to 9.7 percent in the entire metro region), but that share was 19.4 percent for those who have been out of work for over a year, and 20 percent among those with less than a high school degree.19

Figure 1 – District residents aged 17-64 currently not working or in school, by race and educational attainment (2019)

Importantly, trauma is strongly correlated with conditions that make it difficult to get a job in the first place: people with a history of trauma are more likely to have poor educational outcomes. For example, one study finds that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)—one way that researchers measure trauma—more than double the risk of having no educational qualifications.20 Individuals who have suffered from ACEs are also more likely to have poor physical and mental health and increased risk-taking behavior such as higher incidences of substance abuse.21

There is real cost—both a human cost and a social cost—to trauma. District residents who find themselves outside of the workforce are also among those who are most likely to suffer the consequences of concentrated poverty:22 They are more likely to experience physical and mental health problems, economic instability, or be involved with the criminal justice system.23 They live shorter lives.24 They are more likely to be disconnected from their communities, less engaged in civic activities, are less likely to vote or organize, and therefore their communities have a muted voice in the city’s policies.25 Their children, too, will likely have fewer opportunities, creating a vicious cycle that deepens poverty and increases human suffering.26,28 As worker burnout and turnover becomes a larger issue in the District,29 many employers and government agencies increasingly interested in ways to improve worker and participant experiences and outcomes, creating an opportunity to change management practices.

In one way, the renewed focus on the role of mental health and trauma in the workplace reveals an uncomfortable truth: As the impacts of trauma have expanded beyond marginalized communities—especially Black marginalized communities—to the broader population, there is more interest in the topic, and a broader perception of mental health as an issue with which employers must grapple. This is in stark contrast to the times when mental health problems and trauma responses have largely been ignored, seen as a problem largely impacting low-income Black communities.

The report is organized in the following way: Part 1 presents a review of existing literature on the impact of trauma on employability and program design for services—including employment services—available for individuals who have trauma responses. Part 2 presents a case study of Turnaround Inc. and the lessons learned through their three years of operations. It also includes findings from interviews with Turnaround Inc. leadership, and representatives from various case management agencies who have worked with Turnaround Inc. Part 3 concludes with recommendations on policy and practices that could be adopted both by the public sector and private employers who wish to create opportunities for success for their employees who have experienced traumatic events.

PART 1

KNOWLEDGE: What we know about the impact of trauma on the work and life outcomes of individuals

The large body of research on the impact of trauma on life can be loosely grouped into three threads. The earliest thread includes studies that examine the impact of trauma on life outcomes of individuals. This rich literature, which began in late 1990s, has established strong connections between trauma and impaired health and life outcomes for individuals who have trauma responses. A second thread of research has examined the incidence of trauma among participants of social safety net programs and associated work readiness and employment programs. Not surprisingly, this research found a higher incidence of trauma among participants in such programs. Once these linkages were established, researchers turned to study how trauma-informed practices can improve physical and mental health and life outcomes of individuals. This third thread of research has shown that finding the right tools for trauma-informed interventions can be difficult, but once done, could have significant success.

What is trauma?

Trauma is defined as the response to an event (or events) that evokes fear, helplessness, and other psychological and often physical symptoms in an individual. Events that can potentially cause trauma responses can include physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, loss of a loved one, domestic violence, homelessness, incarceration, medical events, addiction, community violence, and more. Trauma symptoms can include fear, anger, agitation, sadness, racing heart, changes to eating and sleeping patterns, fatigue, inability to concentrate, intrusive images, confusion, inability to articulate thoughts, isolation, substance abuse, violent outbursts, and lower senses of trust, safety, and self-esteem. Many people with trauma responses expect to be judged or rejected by those in authoritative positions, assume people will perceive them negatively, and feel as if they are constantly in crisis.30 Because of these symptoms and responses, everyday workplace interactions like constructive criticism can be seen as a threat to survival.

Linkages between trauma and life outcomes

Early research on the impact of trauma on life and outcomes of individuals was conducted from 1995 to 1997 by Kaiser Permanente in Southern California with data from 17,000 members of their Health Maintenance Organization. This information allowed researchers to link adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) reported by survey respondents to their current health status, behaviors, and life outcomes tracked by the patient health history data collected the HMO. Researchers found that survey respondents who reported a higher incidence of ACEs were at increased risk of negative emotional, physical, neurological, and behavioral outcomes.31 Since then, multiple studies have linked trauma to conditions that could impair a person’s work prospects, including mental health barriers such as depression,32 physical barriers such as autoimmune diseases,33 environmental barriers such as food insecurity,34 and domestic violence.35 As such, individuals who have experienced traumatic events are less likely to be employed, and more likely to be on long-term employment disability support services.36

The impact of trauma on job prospects is especially apparent on the life outcomes of formerly incarcerated D.C. residents. In 2018, the D.C. Policy Center published an analysis of employment outcomes of 9,924 clients served by Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA).37 Of this group, 72 percent (7,165) were considered “employable,”38 and of these, 41.7 percent were employed (2,990), 43.4 percent were unemployed (3,112), and 14.8 percent had an unknown employment status (1,063).39 The study showed that employment outcomes correlated with housing security, type of supervision, and time passed since the client left prison. Interviews with officials and experts on returning citizen affairs showed that trauma and mental health conditions were among the most cited barriers to employment. About a third of CSOSA clients that were the subject of the study had symptoms of mental illness (either previously documented or recorded during the intake process); including constant exposure to violence—such as living in a neighborhood where gunshots are commonplace. Many interviewees described that those who had unresolved trauma responses, caused before they entered prison or from the prison experience itself, lacked the processing or coping skills needed to calmly work through conflict and stressors in the workplace and were more likely to remain unemployed. For them, lack of access to compassionate and timely mental health and stigma attached to mental health services exacerbated work outcomes.

Incidence of trauma among those who receive supports from public programs

A related thread of research examines the incidence of trauma among those who are receiving government supports or participating in government programs. This research is important because while the strong link between trauma and negative life outcomes was known, the incidence of trauma among recipients of government programs was not. According to state reporting, almost a third of TANF participants have a work-limiting health condition,40 along with high rates of exposure to violence and adversity in their families and communities. Studies have shown that participants in social welfare programs like TANF are twice more likely to experience intimate partner violence,41 or have adverse childhood experiences.42

This research has also exposed the cascading impacts of trauma by making connections between participants in social safety net programs and their children: For example, children of parents and caregivers who are eligible for social supports are more likely to have lower academic outcomes43 and impaired executive functioning capabilities44 if they live under stressful conditions, which, in return hurts their future employability and earning potential.45

Success of trauma-informed practices

Once the strong link between trauma and eligibility for social services was established, researchers turned to how these services can be improved by introducing trauma-informed practices, and whether these practices have measurable impacts on client outcomes. The research under this thread is extremely rich, but not conclusive. For example, a desk review of 33 studies on interventions that were specifically designed to address trauma (published between 2009 and 2019) showed that while the use of trauma-informed approaches is on the rise, the evidence on the success of trauma-informed interventions as an effective approach for psychological outcomes was mixed,46 suggesting that both the context and the execution matters. In fact, incorporating trauma-informed practices into social work and supports can be difficult. At its core, trauma-informed care incorporates core principles of safety, trust, collaboration, choice, and empowerment, and delivers services in a manner that avoids inadvertently repeating unhealthy interpersonal dynamics in the helping relationship.47 But implementing these principles in practice requires extensive training of case workers, strong alliances across various service providers, and an increased emphasis on warm, interested, and validating care, which, in some cases, clashes with specific counseling techniques.48

Trauma-informed interventions, when thoughtfully implemented, have been shown to successfully improve the mental health, employability49 and life outcomes of individuals.50 For example, a randomized trial conducted with TANF participants found that participants who received trauma-informed supports reported improved self-efficacy, fewer depressive symptoms, higher earnings, and reduced economic hardship.51 Similarly, a trauma-informed financial empowerment programming implemented in Philadelphia, PA has been shown to increase food security among families with young children.52 Training case workers on trauma-informed care has also shown impact in the context of adolescent substance abuse services,53 and at schools. For example, one study that examined a trauma-informed approach implemented at San Francisco schools found that the interventions both amplified positive outcomes (with students engaging more, missing fewer days, completing more assignments, and receiving fewer discipline referrals or suspensions tied to physical aggression) and improved students’ adjustment to trauma (students were more successful in expressing and modulating emotions, showed improved attention, and were able to form stronger relations with others). Similarly, researchers have shown that trauma-informed care implemented across Massachusetts’ child welfare system and mental health network created stronger connections and communication between mental health providers and the child welfare workers, as well as cross-system collaboration (including schools, and juvenile justice), thereby improving referrals as well as leading to positive child outcomes such reductions in problem behaviors and post-traumatic stress symptoms (especially in older children).54

Our literature review did not find any research on, or evidence of trauma-informed practices adopted in the private sector specifically to improve the success of workers who experienced trauma. There is a large body of research on improving the working conditions for and reducing burnout among staff who work with traumatized clients, such as social workers, police officers, school staff in the aftermath of a violent event, human resources officers, air traffic controllers,55 health care workers,56 and workers at non-profits.57 Beyond that it does not appear, at least from our research, that trauma-informed practices have been adopted by employers in ways that have attracted researchers’ interest. This does not mean that these practices do not exist. But it means that they are not widely adopted, or when adopted, referred to as “trauma-informed practices.”

PART 2

PRACTICE: Turnaround Inc. case study on practices, outcomes, and lessons learned

This section presents a qualitative case study on Turnaround, Inc. including information on the program, participant characteristics, approach and tenets, and lessons learned through three years of operations. While the program served a small number of participants, the organization kept detailed notes on their experiences, life conditions, and work progress, which created a rich background for a qualitative analysis of what types of management practices help maximize success for individuals who have experienced traumatic events and been out of the workforce for a long time. The trainees hired by Turnaround, Inc. faced significant barriers to getting and retaining a job, but the lessons learned from their four years of experience could provide important tools for employers who are ready to make changes to management practices in order to avoid accidentally triggering employees, or work with employees who have been excluded from opportunities due to their experiences with trauma.

Mission and operations

Turnaround, Inc. is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization with a mission to provide permanent employment to individuals with high barriers to getting and retaining employment. Established in 2015 as the management partner in an affordable housing development, Turnaround Inc. launched its Workforce Empowerment Program on March 6, 2017, with an initial group of four trainees. Turnaround Inc. operated as a contracted vendor, providing services to managed residential and commercial buildings throughout the D.C., Maryland, and Virginia area, with trainees hired through the Workforce Empowerment Program performing tasks such as painting, plastering, drywall repair, basic plumbing and electrical services, and turnover services.

The Workforce Empowerment Program was designed around five premises related to funding and operations: First, the program would be financially self-sufficient, with all expenses paid from two sources: earned revenue from property management contract services performed by trainees (at market rate), and development fees through Turnaround’s role as the not-for-profit partner for E&G Group, a for-profit affordable housing provider with properties in the Washington metropolitan area. Second, to ensure independence and full focus on the program’s primary mission, Turnaround, Inc. would avoid direct fundraising appeals, philanthropic gifts, and government grants. Third, trainees would be selected through referrals, from a pool of work-ready candidates with consistent case management and logistical supports (transportation, childcare, etc.). Fourth, trainees were expected to work from the first day of employment and acquire all trade skills training while on the job. And fifth, a continuous pipeline of crew leaders would be developed by cultivating and promoting from within.

At the beginning, the program envisioned that employment alone would be enough to create change for trainees and trauma was not in the forefront. Turnaround Inc. chose painting and other basic turnaround services (preparing vacated apartments for the next tenant) as their core activities because these are some of the most accessible trades that do not require licensing or formal credentialing.58 The skills and experience obtained through the program could be applied broadly to other professions and jobs. Importantly, work was conducted in clean and orderly environments which Turnaround Inc. leadership hoped would minimize triggers among workers.

Turnaround Inc. worked exclusively with residents from Wards 7 and 8 who had difficulty finding and retaining employment. To participate in the program, trainees had to meet at least one of the following four criteria: (i) experiencing, exiting, or at immediate risk of homelessness; (ii) a history of incarceration; (iii) receipt of TANF, SNAP, or housing subsidies; (iv) had been unemployed for a year or longer. The program received applicants through partnership and referrals from social service and case management agencies. These included four agencies (TANF Employment Provider Network at the Department of Human Services, Project Empowerment at the Department of Employment Services, the Pathways Program at the Office of Neighborhood Safety Engagement, and the Department of Veteran Affairs), and three private sector partners (Operations Pathways, Community Connections, and Hope Village). Turnaround specifically sought out partners that provide additional supports, especially housing, to ensure that the trainees have the necessary basic needs to be able to come to work.

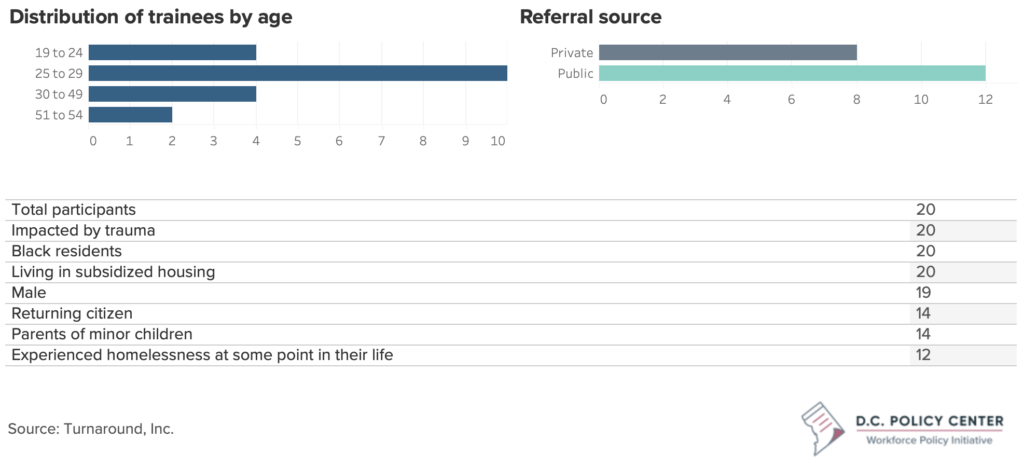

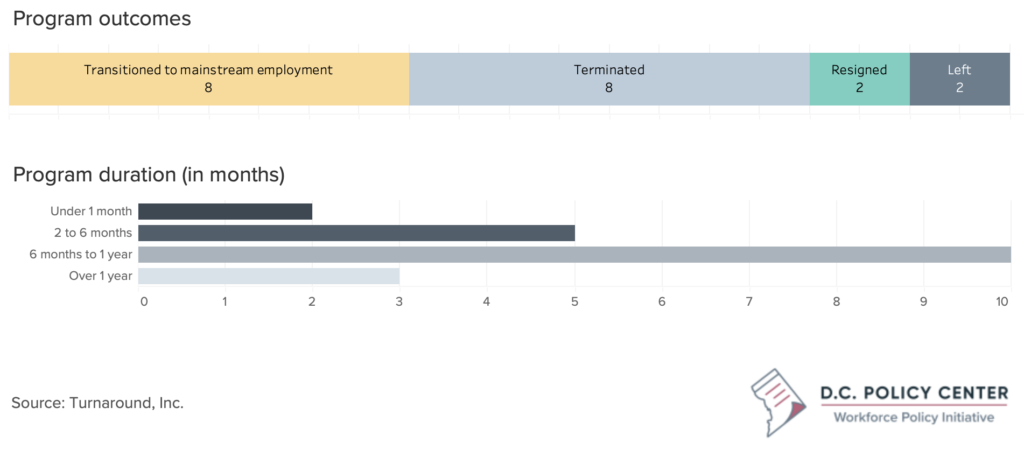

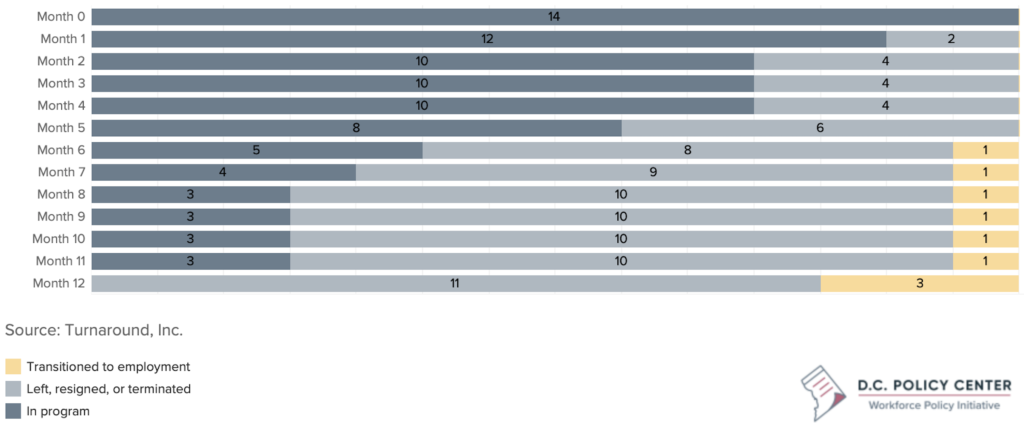

The Workforce Empowerment Program was operational for three years during which time it employed 20 trainees. Among this group, eight participants successfully transitioned to mainstream employment, eight were terminated for performance or behavior, and four resigned or otherwise left the program. Turnaround Inc. paused the Workforce Empowerment Program in January 2021 for evaluation. At that time, all current members of Turnaround’s workforce took jobs within E&G, so no one lost employment due to the suspension of field activities.

Workforce insights

Turnaround Inc. trainees were all Black residents of Washington, D.C.’s Wards 7 and 8, living below the federal poverty line at the time of their employment. Their ages ranged between 19 and 54, with an average age 31, and a median age of 26. Additionally, case records reveal that all participants experienced trauma from violence, poverty, or both; all lived in subsidized affordable housing, and were unemployed for two years or more prior to joining Turnaround, Inc. Fourteen of the 20 trainees were returning citizens who served an average of five-year sentences. Fourteen were parents of minor children, and 12 experienced homelessness at some point in their lives.

Figure 2. Trainee characteristics

Workforce selection and barriers to retention

Turnaround Inc. depended on partner case management agencies for referrals. Partner agencies verified the employment status and personal circumstances of the trainees and Turnaround Inc. interviewed each candidate to determine fit and eligibility. Turnaround, Inc. defined success as six months of continuous employment, at which point participants would have gained significant experience and habits that they could take with them to future employment. To increase success, Turnaround Inc. sought out trainees who expressed an interest in developing a long-term career and demonstrated a commitment to personal advancement, such as obtaining a high school diploma or GED, completing a workforce training program while incarcerated or after release, and clearly stating their goals and priorities.

Despite being motivated and having the best intentions, trainees regularly faced the same, recurring obstacles and challenges in maintaining steady employment. Logistical obstacles, especially lack of reliable transportation to and from work and consistent childcare, were the primary barriers to retention. Trainees also had repeated trauma responses in the workplace which could not be easily resolved or mitigated, resulting in challenges with time management, meeting deadlines, and taking responsibility for work results. These challenges were exacerbated by financial illiteracy, housing instability, and inconsistent case management.

Outcomes and achievements

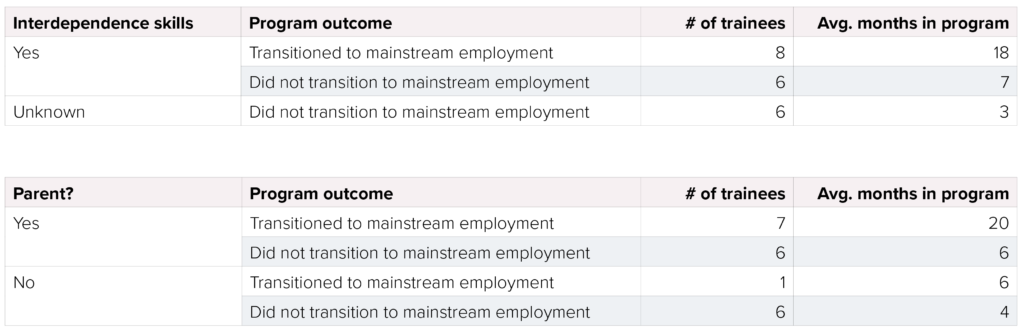

Of the 20 trainees, eight transitioned into mainstream employment, and twelve left the program for various reasons. Termination for cause was the main reason, with eight trainees leaving for poor performance or poor attendance, and one for getting into a fight. Two resigned from the program and two left (one to receive mental health supports, and one when the case management entity ceased operations). The duration of participation varied from under one month to nearly four years (45 months), with an average duration of just over 10 months and a median duration of six months, and most trainees spending somewhere between six months and a year working in the program. Trainees who left the program on their own had the shortest duration of attendance (a median of three months), and trainees who were terminated most frequently left around the six-month mark. In contrast, the median duration of program participation among those who successfully transitioned to mainstream work was a full year.

Figure 3. Program outcomes and participation

Turnaround Inc. conducted over 50 screening interviews to hire 20 trainees and worked hard to create continuous opportunities for advancement and a clear career path for trainees. The intention was to develop leaders internally, from the ground up. Over four years, this group successfully completed more than 1,000 painting and property management jobs and generated over $1 million in revenue from service fees. However, this revenue was not sufficient for Turnaround Inc. to break even. According to Turnaround Inc. leadership, work inefficiencies, low worker productivity, and increased need for management time, generally related to trauma responses and the need time associated with developing new management tactics, on top of the usual costs of business (wages, insurance, supplies, etc.), made it difficult to cover costs and make ends meet.

Lessons learned

Turnaround Inc.’s approach, language, and management practices changed significantly over their four years of operation, as they gained experience with working with individuals with trauma responses. The organization’s leaders identified five important lessons from their work. Some of these observations, such as the need for wrap-around services, are well-recognized, but others are novel, and provide new and important insights that could improve practice in publicly-funded work readiness and employment programs, as well as management styles in the private sector.

Lesson 1: Workforce retention rates improve when end-to-end workforce preparedness training is combined with logistical supports, especially transportation and childcare.

Turnaround Inc.’s experiences showed that trainee success depended on not just availability of supports (both from case management and from the employer) but also the type and quality supports. To increase success, Turnaround Inc. sought out trainees who expressed an interest in developing a long-term career and demonstrated a commitment to personal advancement, such as obtaining a high school diploma or GED, completing a workforce training program while incarcerated or after release, and clearly stating their goals and priorities. But, over time, it became clear that hiring trainees with a demonstrated interest in success alone was necessary, but not sufficient for success.

Trainee achievements improved with both robust partner agency case management and employer supports. Importantly, success depended on strong relationships and close collaboration between Turnaround, Inc. and the case managers from partner agencies, especially for the first six months of employment. For one, partner case management agencies provided suitable and eligible referrals and verified the employment status and personal circumstances of the trainees. Importantly, Turnaround, Inc. turned to case managers for support when trainees were facing logistical challenges getting to work or obtaining child-care, or if a trainee was experiencing personal issues that interfered with their work. Coordination between Turnaround Inc, and case management agencies across approach, training, and support worked in conjunction with one another led to higher retention rates, promotion, and skills attainment.

Additionally, a trauma-informed approach may need to include therapy and training for government program participants on how to navigate common conflicts and manage responses. Programs have often placed much needed focus on reducing barriers to getting to work including inadequate transportation, lack of affordable childcare, food insecurity, and housing insecurity. However, only addressing logistical barriers fails to recognize or reduce the real and serious psychological barriers that trauma can create. Counseling, training, and therapy can help individuals mitigate emotional and psychological barriers to work. These kinds of supports for employees could help them develop coping strategies, self-awareness of symptoms and responses, and resilience to challenges.

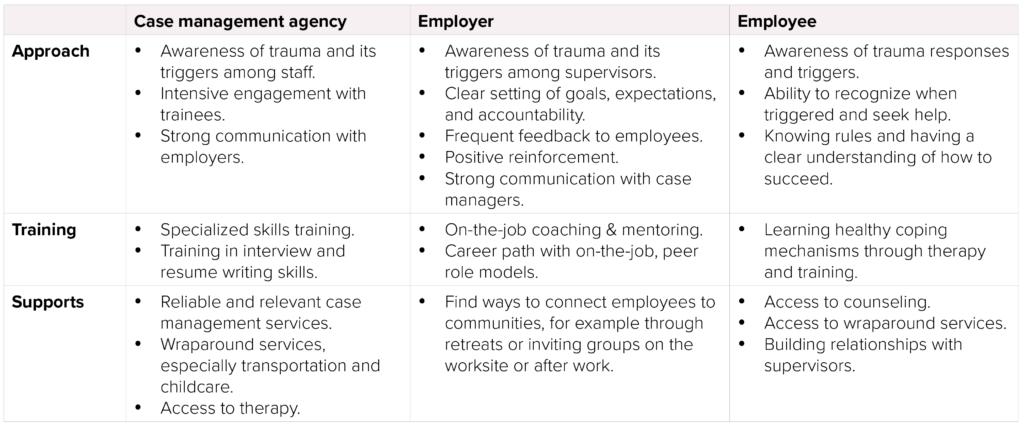

Table 1. Factors contributing to trainee success when employed in coordination

Trainee Insights

Q. is a returning citizen who served more than four years in prison, and was referred to Turnaround, Inc. approximately six weeks after his release. Q. was raised by single mother and has strong relationships with her, as well as his sister and girlfriend.

Q. was energetic and highly motivated at the time of his hire and expressed a desire to progress and achieve promotion. He learned quickly and followed direction well. However, his past involvement in gang activity exposed him to potentially dangerous situations.

Five months into his employment with Turnaround, Inc., Q. was held at gun point in his home. He was terrified and fled the immediate area. His supervisors were unable to locate him for several days and worked together with his case managers and family members to eventually find him. After this incident, Q. was fearful of being followed and of being attacked while on the job site. His anxiety impacted the rest of the crew, triggering traumatic responses from two of his coworkers. Q.’s supervisors conducted many one-on-one check-ins with him and offered him additional time off work to secure safe housing and transportation. They also encouraged him to pursue therapy and lean into his interdependent supports.

Q. was plagued by transportation issues and housing instability, despite strong performance and high motivation. A violent conflict with roommates forced him to move outside the city. When the Covid-19 pandemic struck, he was unable to get to work due to reduced public transportation access. He was ultimately overwhelmed by obstacles and unable to maintain consistent employment.

Q. sustained more than six months of full-time employment. He demonstrated many of the traits that often culminated in higher trainee achievement: close relationships with family and friends and regular interaction with his case managers. He had a positive outlook and high hopes of following in his mother’s footsteps by becoming a maintenance technician. He regularly spoke of his determination to make his mom proud. He gained trade skills and job site experience. Importantly, he was encouraged by his own progress.

But the challenges Q. faced—housing instability, lack of adequate transportation, exposure to illicit activity, financial illiteracy—hindered his success. Q. would have benefited from stronger relations with his case manager, mentoring to help navigate the steps required for a mainstream career, and more robust housing and logistic supports. Q. would have also benefited from mental health supports to help him with PSTD-related symptoms.

Source: Case notes kept by Turnaround, Inc.

Lesson 2: Consistent, sustained, and practical case management improved retention.

Trainees referred by case management agencies were more likely to succeed when their agency provided robust programs and supports, built strong connections with trainees, invested in trainee outcomes, and offered opportunities for growth. Trainees who worked with case management agencies that provided their participants with comprehensive end-to-end supports—logistical supports such as transportation to childcare, housing supports, and training to increase financial literacy and understanding of professional expectations—were more likely to succeed. Retention was also more likely for trainees who had strong relationships with their case managers and felt supported by their referral agency. This happened when trainees had routine, intensive interactions with case managers, and did not have to change case managers frequently.

Table 2. Characteristics of successful case management partners

Program insight: Project Empowerment

As a part of this project, the D.C. Policy Center interviewed representatives from the District’s Project Empowerment program, which is based in the Department of Employment Services, and works with D.C. residents who have a substantial need for intensive employment assistance.59 Project Empowerment is a transitional employment program that provides job readiness training, work experience, supportive services, and job search assistance to District residents who face multiple barriers to employment. It serves clients between the ages of 23 and 54.60 Many of the participants in the Project Empowerment are referrals from the court system and non-profits in the social services areas. Some are just walk-ins who have heard about the program through word of mouth.

Participants of the Project Empowerment are generally hired by property management companies, utilities, or transportation agencies. More than half are in property management with jobs as maintenance or grounds keeping workers, or in office support positions. Program data show that 80 percent of the employees retain their jobs after six months.

Project Empowerment leaders noted that almost every participant has some type of trauma—small to large. Having strong case managers, strong supports, and wraparound services are key for client success. The program also provides robust training for case managers and has included in-house behavioral support services (with supports from the Department of Behavioral Health) in its case management to positively engage participants. Program leaders have observed that in addition to traditional workforce supports, counseling to change how participants emotionally regulate and identify triggers, and use of positive coping mechanisms are key for success. They have also observed that for returning citizens, severity of charge is not correlated with success: Some of the program participants with the most intense charges are employees with the best work ethic and outcomes.

Project Empowerment leaders had the following observations for employers: First, employers who are willing to look past the stigma of incarceration provide wider avenues of success for program participants. But this is not enough. They must also adopt management techniques such as avoiding trigger words, changing their language while talking with employees, and examining management practices to identify implicit biases toward employees who have had traumatic experiences. They noted that an important thing that employers can do to increase success is to find ways to connect employees to communities such as inviting them to groups on the worksite or after work.61

Lesson 3: Strong social interdependence skills and connection to networks produced success.

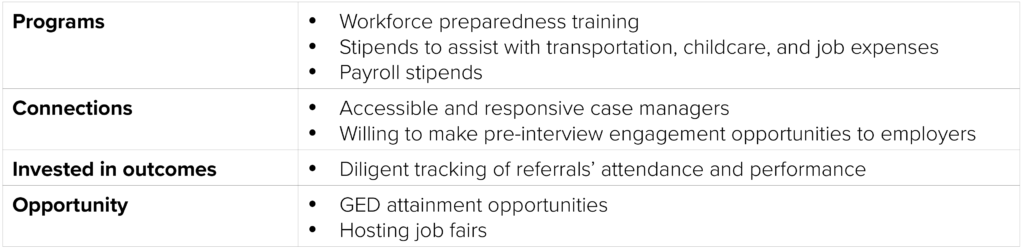

Trainees who were able to develop and sustain social and interpersonal relationships tended to remain employed longer, and were more likely to successfully transition to mainstream employment. All trainees who successfully transitioned to mainstream work had close relations with family and friends, participated in church activities, participated in team sports, or had hobbies or passions like music or car repair, that they could share with others. Even when they did not transition into mainstream employment, they were more likely to stay in the program longer (an average of 7 months compared to an average of 3 months among those who did not have any known social connections). Turnaround, Inc. records show that trainees with strong interdependence skills were also more likely to be promoted from within, as well as achieve other successes such as securing better housing, buying a vehicle, eliminating dependence on subsidized benefits, and saving money.

Table 3. Program outcomes and interdependence skills

Similarly, trainees who had minor children for whom they took responsibility transitioned into mainstream employment more often than trainees who did not have minor children. More than half the parents with minor children transitioned into mainstream employment, whereas only one out of the seven without children achieved this outcome. Information collected by Turnaround Inc. on trainees suggest that social interdependence skills were positively correlated with stronger relations with case managers, personal goal setting and accountability, and responsibility to spouses or other family members.

Trainee Insights

S. is a single mother with the sole custody of her two sons. She had no criminal record, but also had no trade skills and was unemployed for three years prior to her hiring. S. and her sons lived in subsidized housing in a violence-prone neighborhood. S. had been on the waitlist for a housing voucher for over a decade and was desperate to move her family to a safer neighborhood. S. constantly struggled with living costs.

S. has very strong relationships with her family and social connections in her community. She spends much of her free time with her children, mother, grandmother, aunts, cousins, and friends. When hired at Turnaround, Inc., she had a strong relationship with her case manager and participated in multiple workforce preparedness trainings before she was referred to Turnaround Inc.

Not long after she was hired, S. and her sons were caught in a drive-by shooting, when her car was shot nine times. She and her sons were physically unharmed but were traumatized. After the shooting, S. exhibited signs of PSTD, feeling depressed, hopeless, exhausted, and anxious. Her supervisors at Turnaround, Inc. provided time off work, and engaged her in numerous one-on-one coaching sessions to map out her long-term career path. The purpose was to help her feel safe and supported, while also offering her a renewed sense of empowerment and control.

S. sustained over three years of full-time employment with Turnaround, Inc. where she developed skills in drywall repair and painting, electrical, plumbing, and carpentry. She was the first trainee to be promoted from within to lead crews and manage job sites. After three years, she transitioned to a leasing consultant position with Turnaround Inc.’s partner company, E&G Group. One of S.’s sons was hired by Turnaround Inc. after S. left, and he too transitioned into mainstream employment as a maintenance technician with E&G. S. hopes to become a certified property manager and is saving to move to a different neighborhood.

S.’s achievements followed from her clear goals from the first day of her employment. She maintained an unwavering vision for herself and her children and worked incredibly hard to make that vision a reality. She had many factors that helped determine her success, most notably strong case management, deep ties to family and friends, and her determination to create a safer existence for her family. Her ability to set and execute specific goals helps ensure her continued success. She may have benefitted from access to therapy to address her PTSD.

Source: Case notes kept by Turnaround, Inc.

Lesson 4: Returning citizens will benefit from employers who recognize the uniqueness of their points of reference.

Experience with the criminal justice system is a common trait among those who were referred to Turnaround, Inc. Among the over 50 potential trainees referred to the program whom Turnaround, Inc. interviewed, 85 percent had a criminal background that included prior felony convictions, and among the 20 Turnaround, Inc. hires, 14 were returning citizens who served average sentences of more than five consecutive years.

Table 4. Program outcomes by returning citizen status

Justice-involved trainees often demonstrated great enthusiasm about joining the workforce but faced challenges in sustaining extended periods of employment. While most of these individuals maintained full-time employment with Turnaround, Inc. for at least six months, there was a sharp decline in retention beyond that point. Information from Turnaround, Inc. files show that of the six of the 14 trainees who are returning citizens had left the program without a positive employment outcome by month five, and among this group, no one had transitioned to mainstream employment.

Figure 4. Timeline of program outcomes for returning citizens

By the end of the full year, five more had left, resigned, or were terminated, and three made the transition to full-time employment. Trainees’ exit from the program oftentimes coincided external factors such as sudden changes in their case management (fewer touch points, new case manager, etc.), housing instability, or logistical challenges—specifically inability to secure reliable transportation or childcare or both, and traumatic events such as physical assault. Trainees who left the program without securing mainstream employment sometimes had a history of substance abuse and oftentimes had little work experience, and therefore struggled with meeting jobsite expectations.

Turnaround Inc. leadership noted that it was important to know about the incarceration histories of returning citizens. Trainees who are returning citizens brought their experiences to work, and often used their history to frame what they have overcome and what they have accomplished, giving voice to soft skills they have developed. This was one of the most important changes to the workplace culture that improved conditions for employment. 62

Trainee Insights

D. is a returning citizen who spent much of his adulthood incarcerated. D. was actively living in a supervised housing facility at the time of hire, where he benefitted from intensive case management. He is a husband and father of five children.

Prior to his sentence, D. had many encounters with gun violence. He survived an in-home robbery where he was shot multiple times in front of his family.

When D. came to Turnaround Inc., he had no previous work experience, and very little experience in managing his finances. He had been released only two weeks prior to his referral. But he was motivated to provide a better life for himself and his family, and learn skills that would propel him toward a career in the trades. Despite his best efforts, he had difficulty focusing, time setting, and was resistant to constructive criticism. He became agitated and aggressive in several instances where he was asked to take more accountability on the job. His supervisors enlisted grounding techniques during those moments to reconnect him with the present and give him a sense of regained control.

Approximately four months into his employment, D. was moved from a supervised housing facility where he had 24-hour case management, to his private residence. His performance and attendance dropped sharply shortly thereafter. He sustained more than six months of full-time employment—a key marker for success—but was terminated after eight months for low attendance, poor performance, and inconsistent time reporting.

D. may have benefitted from a longer period of intensive case-management after his release, access to therapy to address PTSD, and workforce preparedness training that emphasized time-management, conflict resolution, and expectations for professional conduct and productivity.

Source: Case notes kept by Turnaround, Inc.

Lesson 5: Trauma in the workforce requires a trauma informed response.

While trauma affects everyone differently, individuals who experience repeated traumatic events share some commonalities in how they are impacted by trauma, and how they react to it. Some individuals have difficulty regulating emotions such as anger, anxiety, sadness, and shame—this is exasperated when traumatic events occurred at a young age.63 They are more likely to interpret a situation as dangerous, because it resembles, even remotely, previous experience. Trauma might change cognitive processes, making it more difficult to focus, solve problems, or set priorities. Individuals with trauma responses can react in unexpected ways when triggered, for example, by sounds, smells, sights, tastes, touch, body sensations, and emotions, especially fear. These can lead to responses such as aggression (fight); avoidance, deflecting, or fleeing (flight); inability to react (freeze); automatic obedience (fawn); and attempts to self-heal, usually through substance abuse.

Among Turnaround, Inc. trainees, trauma—including from brutal violence, cruel conditions they endured when unhoused, incarcerated, or impoverished—was pervasive. As such, many of the trainees exhibited trauma responses, triggered by fear of the unfamiliar, fear of criticism, fear of termination, or even fear of working in specific neighborhood. Lack of exposure to mainstream workplaces, limited coping mechanisms, and lack of methods to navigate conflicts with family, peers, managers, and coworkers amplified these triggers. Trauma manifested itself in the form of difficulty navigating conflict, ineffective communication, trouble with personal accountability and task ownership, resistance to constructive criticism, and difficulty in managing time. It was common to see “fight/flight/freeze/fawn” responses especially when trainees were expected to take ownership for tasks and be accountable for productivity; or if there was a perception that their job was at stake. Trainees often self-sabotaged when they feared failure and acted out or deflected blame when faced with constructive criticism. Some exhibited defeat and hopelessness when they received standard feedback, often making statements that “nothing works out.” At times, behavior and responses to common workplace practices completely fell out of the realm of what mid-level managers expect in professional environments.

Turnaround Inc. did not begin its Workforce Empowerment Program with a specific initiative to address trauma. However, over time, supervisors adopted a trauma-informed approach that was critical in operational decision making. For example, when trainees exhibited signs of trauma responses or triggering, their supervisor conducted a private verbal check-in and offered some grounding strategies such as calmly helping reconnect the trainee with the “here and now.” This one-on-one communication was critical to determine the source of the trigger and help alleviate the symptoms of post-traumatic stress. Over time, supervisors adopted strategies to reduce triggers, such as assigning trainees to jobs where they would feel the safest, beginning conversations with positive reinforcement, providing clear consequences and goals with tangible steps, and being consistent. These trauma-informed practices were necessary to help trainees succeed, but took time to figure out and implement.

Trainee Insights

G. is a United States Marine Corps combat veteran who served in Operation Desert Storm. After returning home from the war, G. experienced homelessness for nine years. When referred to Turnaround, Inc., G. had been in stable housing for over a year but had been unemployed for more than a decade. G. had suffered from multiple traumatic brain injuries that left him with various literacy and processing challenges. His symptoms of post-traumatic stress sometimes resulted in him dissociating and “shutting down” at work. G. has no criminal background, is part of a large family, and spends much of his free time with family and friends.

G. was Turnaround Inc.’s first hire. He was a hard worker with a positive spirit. He was referred by a private agency but received case management from both public and private agencies and remained moderately engaged with case managers.

One evening while walking home from work, G. was attacked by a group of armed men, who struck him repeatedly in the head with the butt of a shotgun. He was able to fight off his assailants and escaped but the attack triggered a severe episode of post-traumatic stress that lasted weeks.

G.’s supervisors devoted much time and energy to ensuring he had the physical and mental resources he needed. He was provided time off work and was encouraged to seek out therapy through the Department of Veteran’s Affairs. When he returned to work, supervisors checked in with him routinely to assess how he was doing. If he exhibited trauma responses, supervisors employed grounding techniques to calm him.

G. sustained the longest period of employment of any Turnaround, Inc. trainee, staying on for the entirety of program operations. Over his nearly four-year tenure, he hardly ever missed a day of work and mastered skills in painting, plaster and drywall work, and property maintenance. At the end of his tenure, he transitioned to mainstream employment as a maintenance technician.

Source: Case notes kept by Turnaround, Inc.

PART 3

POLICY: How can the government and employers collaborate to create systemic change?

Trauma is a real barrier to work. Both the public sector—especially public programs that serve individuals who have high barriers to employment and retention, and employers who work with them—and the private sector have an interest in creating a stable and functional environment for workers who may have trauma responses. The public sector invests significant resources in job readiness and placement programs, as well as logistical supports such as transportation and childcare for individuals who are looking for gainful employment. Employers, too, have a real stake as they spend millions of dollars each year to replace workers. However, if psychological and emotional barriers are not also addressed, many individuals may not be able to successfully navigate a work environment.

Many important components necessary to support traumatized workers are already incorporated into the policies and practices of agencies working with individuals looking for work. For example, training programs aimed at increasing employment opportunities for vulnerable populations typically incorporate individual logistical supports, time management, task ownership, accountability, and professional conduct among their key offerings, in addition to more traditional workforce supports such as training and education. However, the implementation and scope of these training programs and supports can sometimes be fragmented and do not always match the needs and realities of employers and the workers themselves.

The existing network of agencies and wiling employers can adapt to the needs of vulnerable workers in ways that are cost-effective and yield tangible results. The tangible results will be higher rates of retention and greater productivity for workers, employers, and support agencies. While employers are unlikely to take on a significant role in providing additional supports such as mental health services, they can contribute by increasing their awareness of the issue, adapting their management practices to the needs of workers with trauma experiences, and employing practical strategies and tools that can mitigate the impacts of trauma responses among their employees.

Increasing awareness among employers of how trauma experiences lead to certain behaviors in the workplace can help employers and managers approach management practices in a different way. There is a considerable and growing body of research on trauma, including the groundbreaking work done on Adverse Childhood Experiences with a large cohort of people enrolled in the Kaiser Permanente health care program. There has also been excellent, practical work done in schools, helping students and teachers deal with the effects of trauma responses on classroom behavior and learning. There is less awareness (and less research) on how trauma shows up in the for-profit workplace. It appears that employers, support agencies, and workers themselves would benefit from more information on how trauma manifests in the workplace, common triggers, and methods to avoid them.64

Further, the current pandemic offers a unique opportunity to make the adaptations necessary for success. Stress and anxiety are widespread. The pandemic is a traumatic event for millions of people who have become isolated, lost loved ones, or had their lives disrupted. Trauma has become a central workplace challenge. The experiences of Turnaround Inc. point to practical policies that employers and hiring managers can adopt around communication, continuity, and work environment as they work with public service providers and new employees.

Perhaps the most important systemic change that is necessary is stronger communication, collaboration, and coordination between public program providers and support agencies, case managers, employers, and employees. This begins with the “hand off” of the worker from the support agency to the employer. There must also be consistent feedback from the employer to the support agency once the worker is on the job. There could be an even greater level of continuity if each worker had a mentor from initial recruitment though the first year or so of employment. The costs of and source of payment for this mentor need to be addressed.

Employers can also benefit from engaging with their employees in low-stress environments. When workers interact with their case managers, it oftentimes follows a negative event–trouble at work or at home, for example. But workers must be assured that they are a genuine priority for public case management agencies, and that they are heard. Similarly, if employers only engage with their employees following a negative event, employees are more likely to experience high levels of stress that can result in trauma responses. Looking for opportunities to seek worker perspectives in low-stakes environments, for example, through roundtable discussions or regular meetings, can help build trust, a feeling of safety, long-term value for both the organizations involved and the workers.

Public agencies can help by setting realistic boundaries and expectations for employers. Many employers need clear delineation of their responsibilities as employers, what resources are available to workers, and what workplace practices can be put in place to reduce anxiety and trauma responses. Knowing what supports are available for their workers from public case management agencies, and when to call public partners for such supports, may increase interest among employers in hiring workers with higher barriers to work, and will likely create a more inclusive workplace culture for existing employees.

Workplace practices such as having managers set predictable, reliable, and consistent workplace rules could help workers navigate workplace settings. Techniques employed by Turnaround and other organizations engaging in this work included laying out explicit rules about when to arrive and how the day will go, setting consequences and applying them consistently, and setting tangible rewards and promotional structures and following through on them in a predictable and consistent way. Increasing awareness of trauma and its manifestations for supervisors of other organizations could improve outcomes through increased understanding, reassurance, consistency, and positive reinforcement.

Additionally, public agencies must take additional steps to ensure that workers are ready for the psycho-social stressors they will encounter at work. Our research and the Turnaround Inc. case study suggest that many workers who have completed public programs are not work-ready. This has less to do with the skills training they received, and more to do with a lack of familiarity with the demands, expectations, and protocols of the mainstream workplace. Workers need to be able to anticipate common workplace challenges and experiences such as receiving constructive criticism, being responsible for outcomes, and navigating professional disagreements. To do this, they must know what triggers trauma responses for them and be able to employ coping strategies to manage those responses. Better coordination between programs, case managers, employers, and employees in defining elements of work readiness and preparing individuals can improve workforce outcomes.

Finally, employers must look for ways to balance privacy with the need for personal information. The need to respect worker privacy and the laws protecting worker confidentiality can sometimes make it difficult to identify the needs and unique challenges faced by traumatized workers. Turnaround Inc. trainees often used their previous experiences as a reference point in setting goals and plans and defining success. When workers’ pasts include stigmatized experiences such as incarceration and experience with the criminal justice system, they are less willing to use these references, unless supported by the managers and employers. But employers are not always comfortable discussing past experiences, and sometimes they may be prevented by law from doing so. Employers can address this issue by regularly communicating with employees about their needs and wellbeing, being clear about their organization’s investment in the mental health and success of its workforce, and regularly communicating and demonstrating that employees are a priority.

Next steps

Trauma is pervasive and affects not only public-program participants, but potentially a large share of the workforce. Additionally, research has shown that trauma-informed approaches and interventions improve mental health, employment outcomes, and life outcomes for individuals. Because of this, it is important for public service agencies, employers, and individuals to learn about trauma, how it can impact daily life and the workplace, and learn strategies to manage responses and improve employment outcomes.

Many employers may be resistant to this task, seeing it as beyond the scope of the workplace, but even small changes can make big differences. As previously discussed, small changes to management styles can help avoid triggering employees and create more inclusive work environments. As a large percentage of the population potentially has trauma responses, these techniques are likely helpful in most workplaces.

We know through previous research and the experiences of Turnaround and other organizations that many steps can be taken to increase awareness of trauma, improve the lives of workers, and improve employment outcomes. Some steps this study has identified include asking workers what they need to thrive, learning from the experiences of individuals who have navigated trauma responses and learned how to utilize healthy coping mechanisms, identifying what resources are available to employees and employers and making sure these resources are communicated, and creating greater awareness of trauma, its pervasiveness, and its manifestations. Additionally, increasing the quality and quantity of wraparound services, increasing coordination between case workers and employers, and implementing practical strategies to mitigate trauma responses (such as setting clear boundaries and expectations, setting tangible rewards and applying them consistently, and approaching conversations with positive reinforcement) will likely all contribute to an improved employment experience.

The impact of trauma in the for-profit workplace is a relatively new area of research and could benefit from additional focus and exploration. Future study is needed to fully understand the effects of trauma and what methods are most successful to support affected individuals. Importantly, the development of management techniques and research should include engagement with affected communities to understand, improve, and implement trauma-informed management practices in the workforce. As our cultural and scientific understanding of trauma develops, we look forward to future insights and implementations of trauma-informed supports for individuals in the workplace.

Endnotes

- For details, see FY21 Workforce Development System Expenditure Guide Accompanying Document published in February 2022, and available at https://dcworks.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dcworks/publication/attachments/FY21-Accompanying-Document.pdf.

- This excludes funding for adult charter schools. For details see the FY2020 Expenditure Guide at https://dcworks.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dcworks/publication/attachments/FY21-Expenditure-Guide.xlsx and the Accompanying Document at https://dcworks.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dcworks/publication/attachments/FY21-Accompanying-Document.pdf.

- And this amount excludes wraparound services supported by public funding such as housing, transportation, and childcare supports many of the participants receive. For example, according to the Administration for Children and Families, the District’s total TANF funding (including federal and local resources) in Fiscal Year 2020 was $316.4 million (source: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ofa/fy2020_tanf_and_moe_state_pie_charts_092221.pdf). Of this amount approximately 11 percent ($37 million) was spent on childcare services. The same agency reported that 44 percent of TANF participants in the District also took part in workforce training and readiness activities (source: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ofa/wpr2020table01a.pdf).

- The Expenditure Guide provides sporadic information in outcomes. For example, in 2019 (the last full year before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic), of the 1,800 participants who completed one of the six programs offered by the D.C. Housing Authority, 221 participants who were employed at the 30 and 60-day employment check-in. Of the approximately 1,000 participants in the programs offered by the Department of Disability Services, about 18 percent had a job two months after they completed the program. And of the nearly 11,000 participants who were served by the Department of Human Services programs (provided for TANF and SNAP participants), approximately 1,000 completed a credentialing program, and job placement rate was approximately 36 out of 1,000 participants. The Department of Energy and Environment offered five programs which enrolled 369 participants. Of this group, 296 completed their program, and 28 found jobs. The total cost of this programming was $2.9 million.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, JOLTS Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) Research Estimates. Available at https://www.bls.gov/jlt/jlt_msadata.htm.

- CEL & Associates and National Apartment Association (2020), “Multifamily Employee Turnover Rates: 2010-2019,” Units Magazine, 2019.

- This estimate is based on the Work Institute’s survey of approximately 3,000 employers (available at https://info.workinstitute.com/hubfs/2020%20Retention%20Report/Work%20Institutes%202020%20Retention%20Report.pdf), which suggests that the cost of turnover is approximately the equivalent of a third of employee salary. The estimate combines this information with BLS data on occupational statistics, which show that in 2020, real estate and leasing sector in D.C. had 7,300 non-managerial positions with a median salary of $46,000.

- Timothy R. Hinkin, Brooks Holtom, and Dong Liu (2012). “The Contagion Effect: Understanding the Impact of Changes in Individual and Work-Unit Satisfaction on Hospitality Industry Turnover.” Available at https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/71059.

- Estimate based on BLS data that shows in 2020 there were 36,000 workers in DC in service occupation in food and accommodations sector, with a median salary of $33,000.

- Turnover information is from ADP Workforce Vitality Reports, 2021 Third Quarter.

- In 2020, an estimated 9,200 employees worked in non-managerial construction occupations in the sector in D.C. with a median salary of $57,000.

- For details, see the American Psychological Association at https://www.apa.org/topics/trauma. According to the Wendt Center, it is the individual’s response to an event that determines if the event is traumatic, not the nature of the event itself. Wendt Center Trauma Presentation April 2021.

- Robin Selwitz (2018). Obstacles to employment for returning citizens in D.C., D.C. Policy Center, Washington D.C. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/barriers-to-employment-for-returning-citizens-in-d-c/.

- Topitzes, J., Mersky, J.P., Mueller, D., Bacalso, E., & Williams, C. (2019). Implementing Trauma Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (T-SBIRT) within Employment Services: A Feasibility Trial. American journal of community psychology.

- Dawn Griffin, “Behavioral Health in the Workplace: Can Trauma-Informed Systems Help?,” Live Well San Diego, accessed March 3, 2021.

- For example, when Chicago Public School teachers were asked to include trauma-informed practices into their daily work with their students, some found these practices clash with what the teachers defined as “expected behaviors” from students. It took an exceptional amount of work on part of principals to shift focus from certain student behaviors to strategies for improving outcomes that reduced the chances of dropping out of school. We find parallels between this example and workplace where trauma-informed workplace practices must similarly shift focus to positive behaviors that are indicators of employee success and longevity. For details, see Emily Krone Phillips, The Make-or-Break Year: Solving the Dropout Crises One Ninth Grader at a Time (The New Press, 2019).

- Interview with Gabrielle Cesar-McBride, October 28, 2021.

- These include residents who reported they are available for work (6,724), not available for work due to an illness or another reason (2,525), and those who did not report details on their availability (44,222). The data are estimates developed using the American Community Survey’s one-year microdata for 2019.

- Data from Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Systems, available here: https://nccd.cdc.gov/weat/#/analysis.

- K. Hardcastle et al., “Measuring the Relationships between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Educational and Employment Success in England and Wales: Findings from a Retrospective Study,” Public Health 165 (December 1, 2018): 106–16. Available at https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PUHE.2018.09.014

- Vincent J. Felitti and Robert F. Anda, “The Relationship of Adverse Childhood Experiences to Adult Medical Disease, Psychiatric Disorders and Sexual Behavior: Implications for Healthcare,” in The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health and Disease, ed. Ruth A. Lanius, Eric Vermetten, and Clare Pain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 77–87. Available at https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511777042.010.

- Rusk D. (2018). Concentrated Poverty—The Critical Mass, D.C. Policy Center, Washington, D.C. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/concentrated-poverty-critical-mass/.

- See, for example, Erickson, D. et, al, editors (2008). “The Enduring Challenge of Concentrated Poverty in America: Case Studies from Communities across the U.S.” The Federal Reserve System and The Brookings Institution.

- Chetty R., M. Stepner, S. Abraham, et al. The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–1766.

- McBride, A., M. Sherraden, and S. Pritzker. (2006). Civic Engagement among Low-Income and Low-Wealth Families: In Their Words. Family Relations, 55(2), 152-162. Retrieved February 23, 2021. Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/40005326.

- For example, over time, economic segregation among the District’s Black residents have increased. As more affluent Black residents have moved away from the District of Columbia, poverty has deepened in some parts of the city. For details, see Rusk D (2018). The Great Sort Part II, D.C. Policy Center, Washington, D.C. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/the-great-sort-part-ii/.

- Chetty R, N. Hendren, M. R. Jones, S. R. Porter (2018) “Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: an Intergenerational Perspective” Quarterly Journal Of Economics, Volume 135, Issue 2, May 2020, Pages 711–783. Available at https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/race_paper.pdf]

Recognizing trauma reactions as a barrier to workplace retention and in reaction to workplace interactions is not new; and the idea of adopting trauma-informed practices is not novel. But trauma experiences became more frequent post COVID-19, making this a more pressing issue for employers. Estimates showing that over a quarter of the population showed symptoms of a trauma-related disorder after the pandemic.27Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, et al. Mental Health, Substance Use, and Suicidal Ideation During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020; 69:1049–1057. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

- Sayin Taylor, Y. and McConnell, B. (2022). The tepid monthly employment numbers in D.C. hide great churn. D.C. Policy Center. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/tepid-monthly-employment-numbers-churn/

- Wendt Center Trauma Presentation, April 2021.

- See, for example, Felitti, V., Anda, R. F., Dale, N., David, F. W., Alison, M. S., Valerie, E., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258; and Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. Available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

- Cambron, C., Gringeri, C., & Vogel-Ferguson, M. B. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences, depression, and mental health barriers to work among low-income women. Social Work in Public Health, 30(6), 504–515. Available at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19371918.2015.1073645

- See, for example Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186; Danese, A., Moffitt, T. E., Harrington, H., Milne, B. J., Polanczyk, G., Pariante, C. M., et al. (2009); Adverse childhood experiences and adult risk factors for age-related disease: Depression, inflammation, and clustering of metabolic risk markers. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(12), 1135–1143; Dube, S. R., Fairweather, D., Pearson, W. S., Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., & Croft, J. B. (2009). Cumulative childhood stress and autoimmune diseases in adults. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(2), 243–250. Available at https://doi.org/10.1097/Psy.0b013e3181907888.

- Chilton, M., Knowles, M., Rabinowich, J., & Arnold, K. T. (2015). The relationship between childhood adversity and food insecurity: ‘It’s like a bird nesting in your head’. Public Health Nutrition, 1–11. Available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980014003036.

- Adams, A. E., Bybee, D., Tolman, R. M., Sullivan, C. M., & Kennedy, A. C. (2013). Does job stability mediate the relationship between intimate partner violence and mental health among low-income women? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 83(4), 600–608. Available at https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1111%2Fajop.12053.

- Sansone, R.A., Dakroub, H., Pole, M., & Butler, M. (2005). Childhood Trauma and Employment Disability. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 35, 395 – 404.

- Robin Selwitz (2018). Obstacles to employment for returning citizens in D.C., D.C. Policy Center, Washington D.C.

- CSOSA classified a client as “employable” if the client is not retired, disabled, suffering from a debilitating medical condition, receiving Supplemental Security Income, participating in a residential treatment program, incarcerated, or participating in a school or training program.

- Results are current as of March 5, 2018.

- Dan Bloom, Pamela J. Loprest, and Sheila R. Zedlewski (2011). TANF recipients with barriers to employment. Urban Institute, Washington D.C. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/25396/412567-TANF-Recipients-with-Barriers-to-Employment.PDF.