A return to in-person learning at the start of school year 2021-22 also presented challenges for students with disabilities as they had to navigate changes to service delivery; staffing shortages; and COVID-19 protocols, exposure quarantines, and social distancing. While we can quantify some metrics related to how students with disabilities navigated school year 2021-22, it is difficult to know how everyday services looked different from previous school years. To find out more, the D.C. Policy Center reached out to parents of students with disabilities, community partners, and District agencies to ask how services related to IEPs looked different during last school year. We also asked what services and opportunities should be expanded for students with disabilities.

While virtual learning during school year 2020-21 presented challenges to all students, students with disabilities experienced significant impacts to their instruction because of obstacles with service delivery or difficulties identifying students who need additional interventions in the virtual format.[i] Students with disabilities were among those prioritized for an early return to physical learning through CARE classrooms in November 2020.[ii] A return to in-person learning for all students at the start of school year 2021-22 also presented heightened challenges for students with disabilities. In addition to navigating new COVID-19 protocols, staffing shortages and attendance issues, commonly related to COVID-19 quarantines, presented challenges for students with disabilities to receive appropriate and required services.

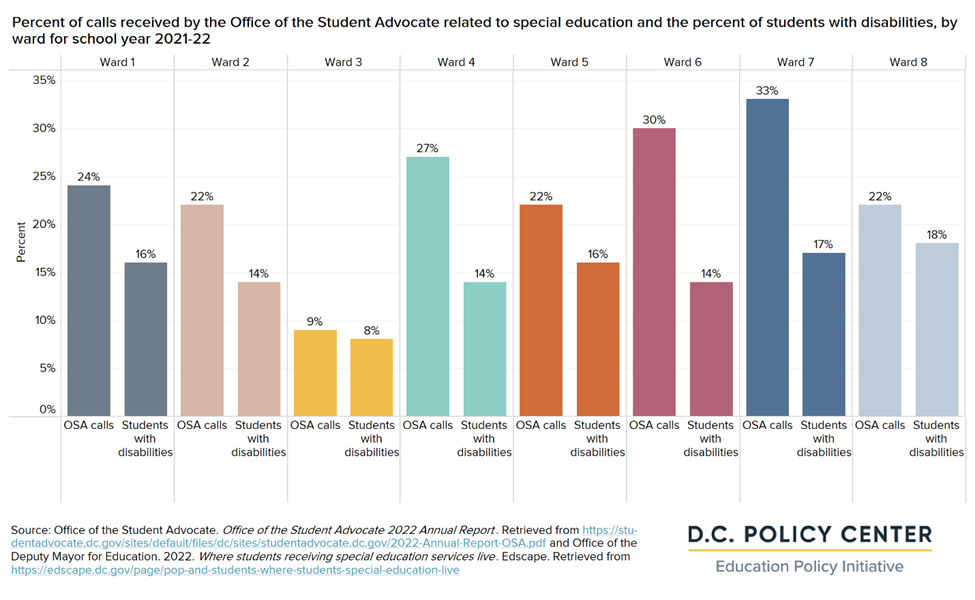

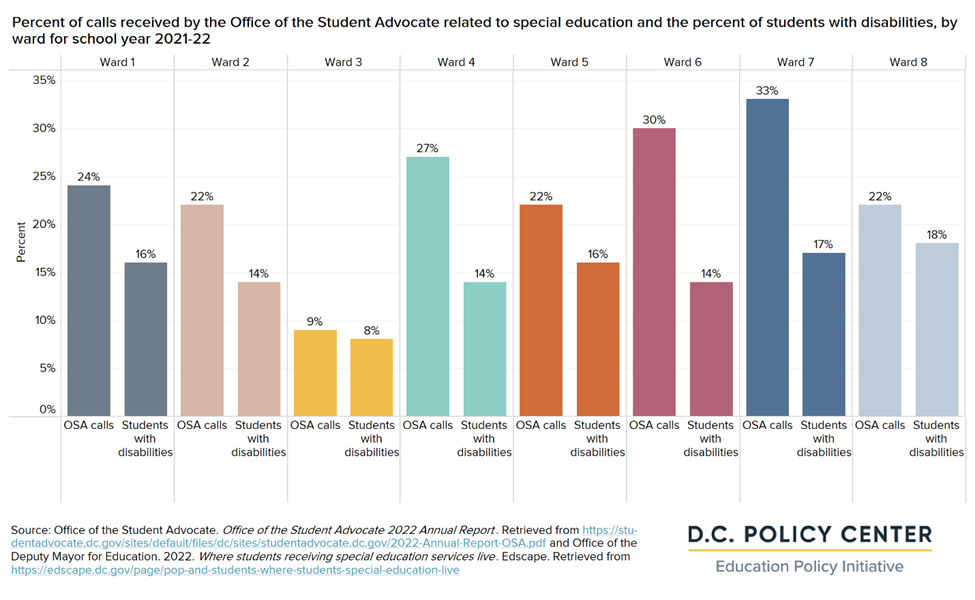

In D.C., 15 percent of students were students with disabilities in school year 2021-22. However, concerns with delivering services to these students is frequently a concern for parents. The Office of the Student Advocate (OSA) and the Office of the Ombudsman of Public Education both receive calls seeking assistance from parents of public school students. Both agencies reported high frequencies of calls related to special education concerns during school year 2021-22. Concerns related to special education was the most common type of call received by OSA (21 percent of all calls), [iii] and the third most common type of call received by the Office of the Ombudsman (30 percent of all calls). [iv] Across both offices, calls related to special education were commonly made by parents of students who already had an IEP or 504 plan in place (30 percent of special education calls from OSA and 76 percent of calls made to the Office of the Ombudsman). Ward 7, where 17 percent of students are students with disabilities, has the highest rate of calls related to special education, at one-third of calls to the OSA. The Office of the Ombudsman received the highest number of calls regarding special education from Wards 7 and 8.

Across both agencies, top concerns included service delivery. The Office of the Ombudsman found that the most common trend identified was for students not receiving the number of service hours written into Individualized Education Plans (IEPs). In requests received by OSA, the top four topics mentioned during calls related to special education were IEPs, special education placement, not enough support provided, and transportation.

Issues with service delivery reported by parents were likely related to staffing shortages across schools. Seven percent of special education teaching positions were vacant as of October 2021.[v] This vacancy rate could have impacted the type, frequency, or consistency of services at the beginning of the year. The Office of the Ombudsman heard from families that many students were not receiving speech and language services because of staff shortages. They also reported that staff shortages may have resulted in students having to attend a general education classroom because schools lacked enough staff for a separate special education classroom. For OSA, they reported that for many, rather than calling with issues with identification, many families were calling with concerns about IEP implementation such as too few service hours or services that were not being provided.

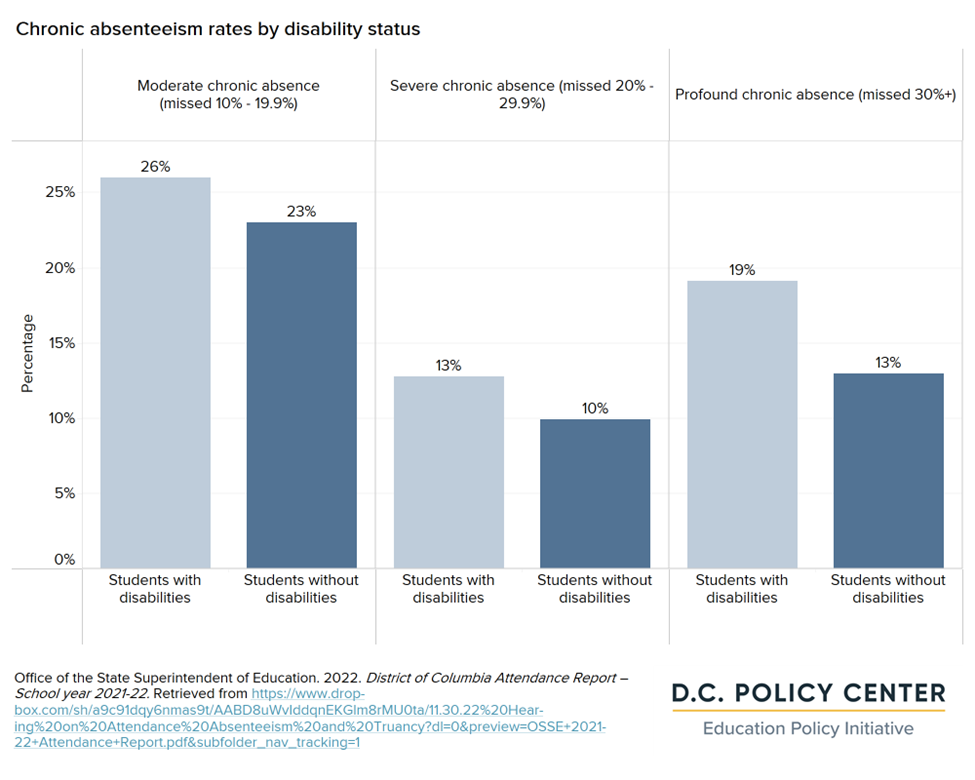

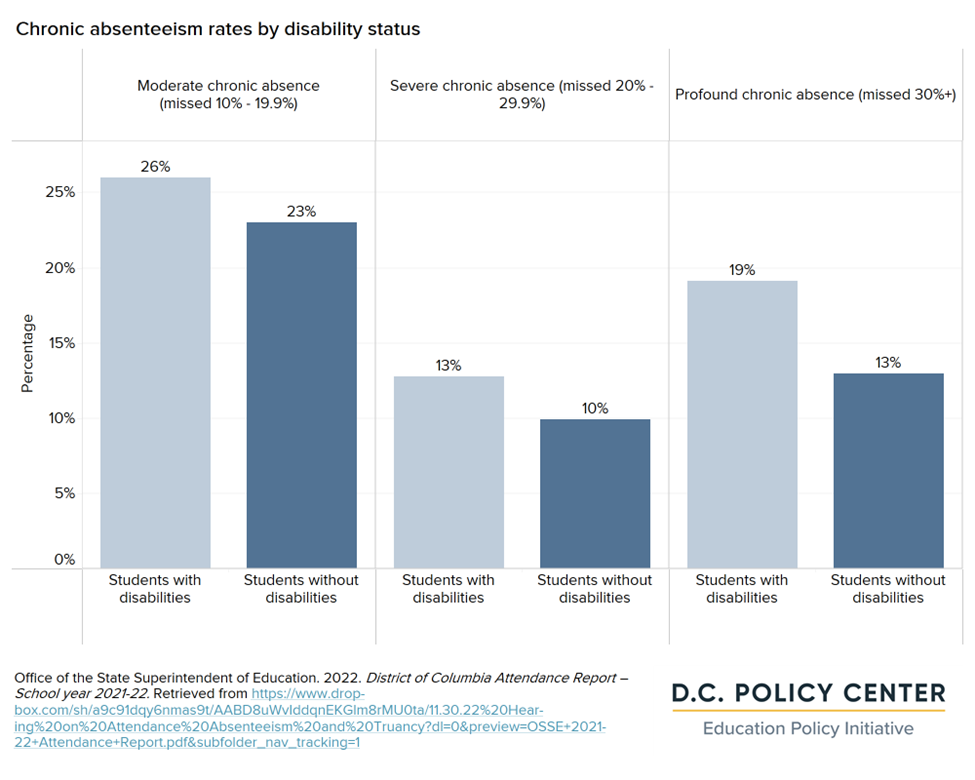

Students with disabilities may also have faced challenges receiving services last school year because of attendance patterns. The rate of chronic absenteeism, or missing at least 10 percent of the school year, for all students was higher at 48 percent during school year 2021-22 compared to previous years, and even higher for students with disabilities at 58 percent. This is an increase or 18 percentage points for both all students and for students with disabilities from school year 2018-19 and could be driven by a rise in excused absences related to COVID-19 quarantines.[vi] Students with disabilities were also more likely to have missed 30 percent or more of the school year – 19 percent of students with disabilities fell into this category compared to 13 percent of students without disabilities. Absences for students with disabilities are important to track because in addition to possible lost class time, they may also be missing services and interventions related to their IEPs that may present additional challenges to make up.

While we can quantify some metrics related to how students with disabilities navigated school year 2021-22, it is difficult to know how the everyday of services related to IEPs varied from previous school years. To find out more, the D.C. Policy Center reached out to parents of students with disabilities, community partners, and District agencies to ask how services related to IEPs looked different during this school year. We also asked what services and opportunities should be expanded for students with disabilities.

Hannah Blumenfeld-Love, Program Manager, DC Special Education Hub and Serena Hayes, Ombudsman for Public Education, DC Office of the Ombudsman for Public Education

Since the pandemic started in 2020, our office has seen a notable increase in family questions and concerns regarding special education. During remote learning, many families noticed learning challenges they may not have seen before. As a result, we saw an increase in caregivers who suspected their child may have a disability and an increase in families looking to have their children evaluated for special education services.

Alternatively, we also saw an increase in questions from families whose children already received special education services. What would those services look like as students switched from in-person instruction to virtual instruction and back again? How would schools address new gaps and challenges that may have emerged during the pandemic?

In response to this increased need, the Office of the Ombudsman for Education was able to partner with OSSE to create the DC Special Education Hub, a new initiative that provides support and resources for families navigating special education in the District. Throughout the past year, we have seen new challenges, but we have also seen schools’ and families’ creativity and collaboration reach new heights.

One positive aspect of the past few years has been the increase in technological engagement. Schools have been able to utilize new digital learning resources and tools to serve special education students in individualized and innovative ways. The widespread use of video conferencing and other communication apps has made IEP meetings and parent-teacher conferences more accessible to working families and those who live or work farther away from their children’s schools. The new challenges we have all faced together also created new opportunities for collaboration between students’ families and school teams. We hope to see this spirit of collaboration continue to grow, as special education is always at its best when families and schools work as a team.

Of course, our special education students also continue to face barriers that have been exacerbated by the pandemic. Schools have experienced significant staffing shortages, particularly when it comes to special education teachers and specialists like speech language pathologists. This has resulted in service gaps and delays for students as schools work to fill vacancies. Moving forward, we hope to see clear plans to serve students when staffing shortages do occur and proactive communication with families.

Zulma Barrera, PAVE Ward 5 PLE Board Member

Zulma is the mother of 3 daughters and wife to fellow PAVE Ward 5 PLE Board member Luis Ledesma. Originally from El Salvador, Zulma has lived in DC since 2005. Her daughters attend Paul PCS and Inspired Teaching School. Zulma is passionate about educational advocacy, particularly school-based mental health resources, supporting immigrant families, and strong partnerships between schools and families!

My daughter was in kindergarten when I first noticed she was struggling in school.

The work the teacher assigned was challenging for her, and her confidence level was low. When I reached out with questions, I was told that the learning difficulties I observed were “normal” for a bilingual child, and as an English language learner myself, I felt my voice was being ignored.

In first grade, my daughter’s struggles grew even more apparent to me. She was having trouble with reading and completing homework on a daily basis. I contacted the school repeatedly asking for an evaluation, and still I got no response. My frustration grew. I could not understand why my daughter was being overlooked, why my calls were being ignored. I feared my daughter would continue to be left behind.

I grew tired of being ignored, switched schools, and ultimately reached out to Advocates for Justice in Education (AJE) to support me in advocating for my child. By working with AJE, I was finally able to get my daughter evaluated. While of course I was happy to see movement, I was incredibly disappointed that critical years had been wasted.

When my daughter finally got an IEP, she was 2 years behind grade level in reading and math. Because of these deficits she had to repeat 3rd grade.

Seeing my daughter struggle, and feel like she was less than and “not smart” because she had not been receiving the support she deserved, broke my heart.

As we entered the pandemic, virtual learning led to further declines. Although my daughter was receiving daily small group support with 6-7 classmates, the format was difficult. Her mind wandered and like most other children, it was hard for her to focus at home.

Being stuck in the house, not socializing, and not mastering content taught over a computer, led to her developing anxiety. Most days she couldn’t even sleep through the night due to the fear she was falling behind yet again.

Since returning in-person, I have seen my daughter grow and improve. However our new challenge is lack of communication from the school. My husband and I are frustrated with the Zoom meetings and emails. We want in-person meetings and more open conversation. We want this so that our daughter is set up for the future she deserves, and so that we can support her in reaching her goals.

Through this experience I’ve learned that people assume immigrant families don’t care about the education of their children. This cannot be further from the truth. We absolutely care, in fact I spent years crying and concerned about my daughter’s progress. It is not lack of concern, but language that is a huge barrier. I am currently taking English classes at Briya, so that I can continue to be a voice for myself, and for parents who need support in advocating for their children. I’m also a PAVE (Parents Amplifying Voices in Education) Ward 5 PLE Board member, to learn about education policy and further develop my parent advocacy.

The system can be confusing and difficult to navigate. It can feel like barrier after barrier is put in your way. I’m not a teacher, I’m not a therapist, I’m a mom. And as a mom I will always do whatever it takes to support my children.

SchoolTalk

SchoolTalk is a nonprofit based in D.C. that supports the D.C. education community in collaboratively addressing complex challenges and creating practical solutions for assisting youth of all abilities achieve success. We work with youth and families to provide programming focused on inclusive education and restorative justice. In our work, we see a lot of the challenges and changes that students with disabilities face each day. IEPs and service delivery changed throughout the school years affected by COVID-19 – from school year 2019-20 to today.

First, IEP delivery during school year 2021-22 was affected by staffing shortages. In our conversations, we learned that the continuity and number of services being provided were changed because of staffing changes – either due to difficulties with hiring or as related to staff attendance. As a result, instead of receiving one-to-one services, students with disabilities may have had to meet with staff in larger ratios more often. Students may have also had to work with different support aides rather than working with one consistently.

Second, secondary transition work-based learning opportunities were more limited. Prior to COVID-19, SchoolTalk worked with schools to provide community work-based learning experiences like mentoring, job shadowing, job site tours, in partnership with local businesses. These in-person experiences are important because in addition to exploring different career options, growing relationships with local businesses can encourage these businesses to hire students who may not have traditional diplomas after they graduate. Because of COVID-19 restrictions, visits largely didn’t happen during school year 2020-21, and we started to bring them back during the following school year. The pandemic changed the DC labor market both in scope of work and staff turnover, impacting the quality and number of business partnerships needed to provide such activities. In addition, schools faced a lot of challenges because of staffing shortages –did not have the availability of staff members to devote to business engagement nor to meet the required student-to-staff ratios for community-based activities. This year, SchoolTalk and the disability community are working to rebuild relations with the D.C. business community and address staff capacity to ensure that students with disabilities have direct linkages to our local labor market through meaningful work-based learning opportunities.

Relatedly, one of the major opportunities that we would like to see expanded is work-based learning opportunities. Because the majority of the jobs in D.C.’s market are filled with people who don’t live in D.C., our students are competing with non-DC residents who commute to work. For many positions, our students are also competing against those who had access to acquire a high school or college degree. Students with disabilities, particularly students with complex support needs, often receive an IEP Certificate of Completion instead of a Standard High School Diploma and may lose out on these positions even though the positions themselves do not require a degree to complete. We want more connections made between youth and employer opportunities such as through panels, work trials, situational and vocational assessments in the community.

We see transportation as a constant and daily challenge for our students. As public safety concerns raise across the city, the demand on our special education, paratransit systems (i.e. Metro Access and private transportation providers funded through disability service systems), and ride sharing companies (i.e. Lyft and Uber) is drastically increasing. In addition, due to the geographical location of various supports and services, many students need to travel outside of their local neighborhoods to access them. According to OSSE’s 2019 Landscape Analysis, we know that at least 1 in 4 students with disabilities travel 2 hours or more to school every day. Transportation systems and local funding for special education and disability related transportation supports struggle to keep up with this demand. Students often miss out on community-based activities simply because they do not have a safe, reliable way to get there. We would like to see access to transportation in a reliable, safe, and consistent manner for students with disabilities both to and from school, in addition to school activities that take place outside the building such as work-based learning experiences or CTE classes.

Julie Camerata, Executive Director, DC Special Education Cooperative

The DC Special Education Cooperative (Co-op) is an innovative and collaborative hub of tested, curated, and shared solutions for special education. The Co-op is a preeminent source for those who want to ELEVATE the way they serve students with disabilities. Since 1998, The Co-op has been developing and delivering innovative programs centered around the needs of students with disabilities and the educators that serve them.

Services related to IEPs look largely the same between this school year, last school year, and the pre-pandemic school years. This is a missed opportunity to better serve our students with disabilities.

DC students with disabilities are performing at the same achievement levels as pre-pandemic: On PARCC, just 7 percent of students with disabilities meet or exceed expectations in English language arts, and 5 percent meet or exceed expectations in math.

As we think about opportunities that schools should provide for students with disabilities, I urge all of us to start the conversation with what teaching and learning experiences we want to provide all students and then align IEPs and related services.

In other words, let’s dream big for students with disabilities and ensure they are getting equitable access to rigorous, grade-level content.

Learning in general education classrooms

Research shows that up to 90 percent of students with disabilities can learn on grade-level when given the right supports. Research also shows that the more time students spend outside of a general education classroom, the less likely they are to be on grade level. Yet, DC students with disabilities are less likely to be in inclusive, general education classrooms, compared to their national peers. In 2020, just 58 percent of students spent 80 percent or more of their day in general education. By ensuring students with disabilities are learning in general education classrooms, alongside disabled and non-disabled peers, students will see more time with grade-level content and a content-expert teacher.

Learning in inclusive environments

Schools should build more inclusive learning environments with a rigorous curriculum and a variety of ways that students can access that learning. For example, Universal Design of Learning, highlighted in our Demonstration Classrooms, allows students to access content on their learning terms. In a math class, that may mean solving a problem using objects and manipulatives; in a science class, that may mean sitting on a bean bag while engaging in understanding the solar system; and in English class, that might mean paired student talk about a text.

Supporting all teachers

To achieve the above, schools must invest in teachers. Professional development for all teachers (general education teacher, special education teachers, English Language teacher, and subject-matter teachers) are critical across implementing curriculum well, regularly looking at student data and student work, creating inclusive environments, and more.

Leading on systemic shifts

LEA and agency leaders are the ones who can make these changes happen, but they require prioritizing students with disabilities and setting bold goals for teaching and learning. From there, schools can adopt the right curriculum for their context, the right approach to creating inclusive classrooms, ongoing and deep professional learning, and more. Sometimes it is as simple as building in time in master schedules that put students with disabilities first that allows these shifts to be possible.

But first, we need to think big and boldly, and not limit ourselves to compliance as the ceiling.