On October 23, the Washingtonian published an alarmist article on what receiving Amazon HQ2 could mean for the region: a massive housing shortage.

The underlying analysis is a brief one produced by the Urban Institute. Though striking a much more positive tone than the coverage by the Washingtonian suggests, the Urban Institute researchers do predict a housing shortage. They modify a recently released jobs and housing analysis by the Metropolitan Council of Governments (COG) for the potential 50,000 jobs Amazon could bring to the region. COG originally identified the gap between the projected supply and the potential need as 65,000 units. The Urban Institute researchers conclude that between now and 2026, Amazon related job growth would require an estimated 40,000 additional housing units, bringing this gap to over 100,000 units. The authors do not speculate on what this might mean for housing prices beyond the observation that housing costs are already high. Their charts do imply that more people could be cost burdened or pushed out to the periphery facing longer commutes if Amazon comes here.

These numbers are indeed drastic, and the implications dire. But, when put in the context of the Metro region’s history, the “Amazon effect” is an unimpressive flare in the region’s chronic housing crisis.

The 50,000 additional employees are important, but this figure is within the usual growth experience for the Metro region.

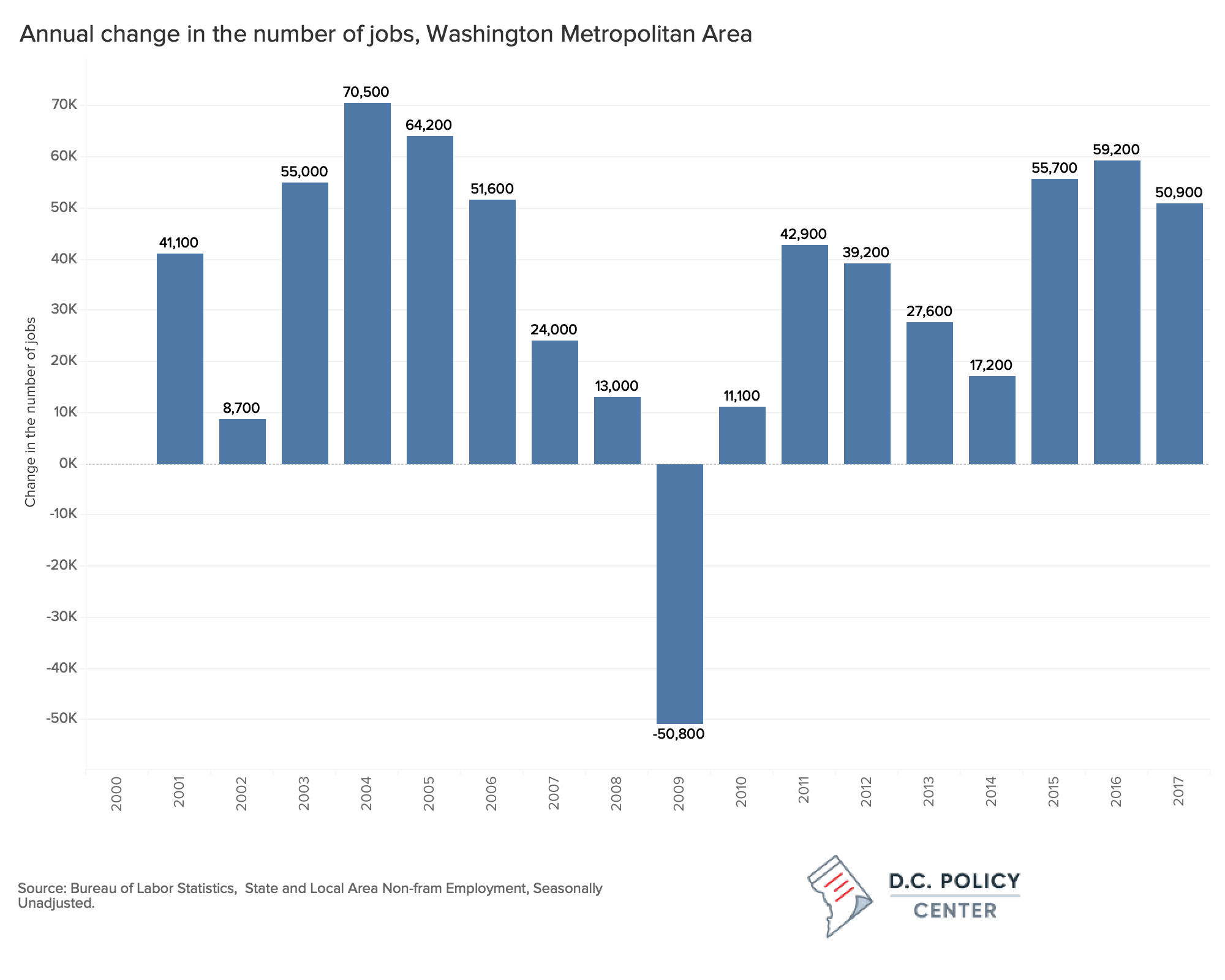

Since 2000, the employment in the Metro region[1] increased by 581,100, an equivalent of nearly 12 Amazons. This period includes two recessions, one very severe. Averaged over these ups and downs, the region has added 34,000 employees each year since 2000—80 percent of a full Amazon. In seven of these seventeen years, including the last three, we absorbed one full Amazon or more in a single year with job growth above 50,000. And in 2009—the year of the Great Recession—we lost one full Amazon.[2]

In 2018, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the total number of employees in the Washington Metro Area was 3.12 million. The most recent cooperative forecast from COG projects that employment will reach 4.05 million by 2030.[3] (If Amazon moves in 2019, that will be the end of the roughly 10-year ramp-up they are planning.) The estimated increase of 934,700 employees is the equivalent of 18 Amazons.

Seen in this context, the 50,000 workers Amazon plans to bring over the next ten or so years is a marginal change in employment in the Metro region.

Some of what Amazon would bring is already in our baseline growth.

An important consideration is whether we should treat the 50,000 workers Amazon would bring in as net-new workers. It is reasonable to assume that at least some of the potential workforce brought in by HQ2 is already baked into the baseline growth projections. While forecasters likely did not account for any specific company in their estimates, they statistically captured some moves by large firms when they incorporate the region’s employment history in their forecast.

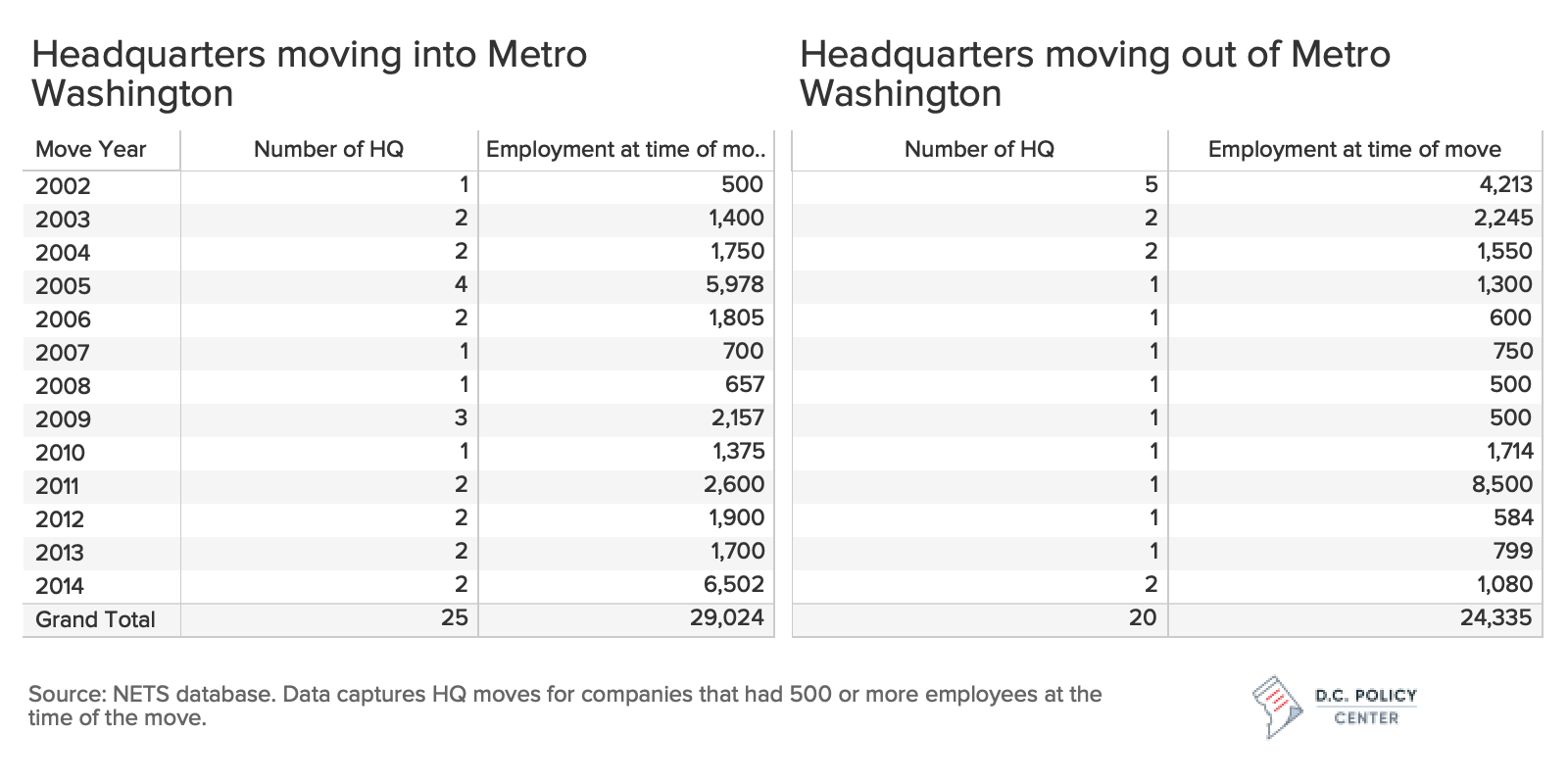

To wit, between 2000 and 2014, the Washington metro region received 44 headquarters[4] with 500 or more employees (at the time of their move) from elsewhere in the country. Combined, these companies brought in 50,494 workers at the time of their move; they might have more or fewer employees today. During the same period, 31 headquarters moved out of the Metro region, taking 34,758 employees with them. We don’t know why these companies moved away, but they have spread all around the country going as far as Anchorage, AK, and as near as Baltimore, MD.

Over time, the presence of a big company like Amazon could lift growth projections. Amazon HQ2 can induce other businesses to locate nearby, offering their services to Amazon or others who do business with Amazon. And the employees of these new firms will add to the demand for goods and services, further boosting employment growth. Indeed, that is what states and cities are banking on when they offer move-in incentives to Amazon. But to achieve this outcome, the region must have the capacity to support growing demand, be it for housing, childcare, or groceries.

Therein lies the problem with the “shortage” analysis: The more we buy into the argument that Amazon will overburden the region, the more we should discount the agglomeration effects or the size of the Amazon multiplier, and hence the size of the consequent shortage. If HQ2 comes to the region, it would demand space and its workers would demand housing. Without quick expansion in supply to meet the new demand for housing (and other things) the cost of living and the cost of doing business could increase, making the region less attractive to the next big company contemplating moving in.

The core counties in the Metro region are expanding.

The Urban Institute researchers focus on the inner counties of the Metropolitan Washington Area. They define this as Montgomery, Prince George’s, Arlington, Fairfax, and Loudoun counties, and the cities located within—Alexandria, Falls Church, Fairfax City. This focus would make sense if most jobs are in these counties and most new residents settle there.

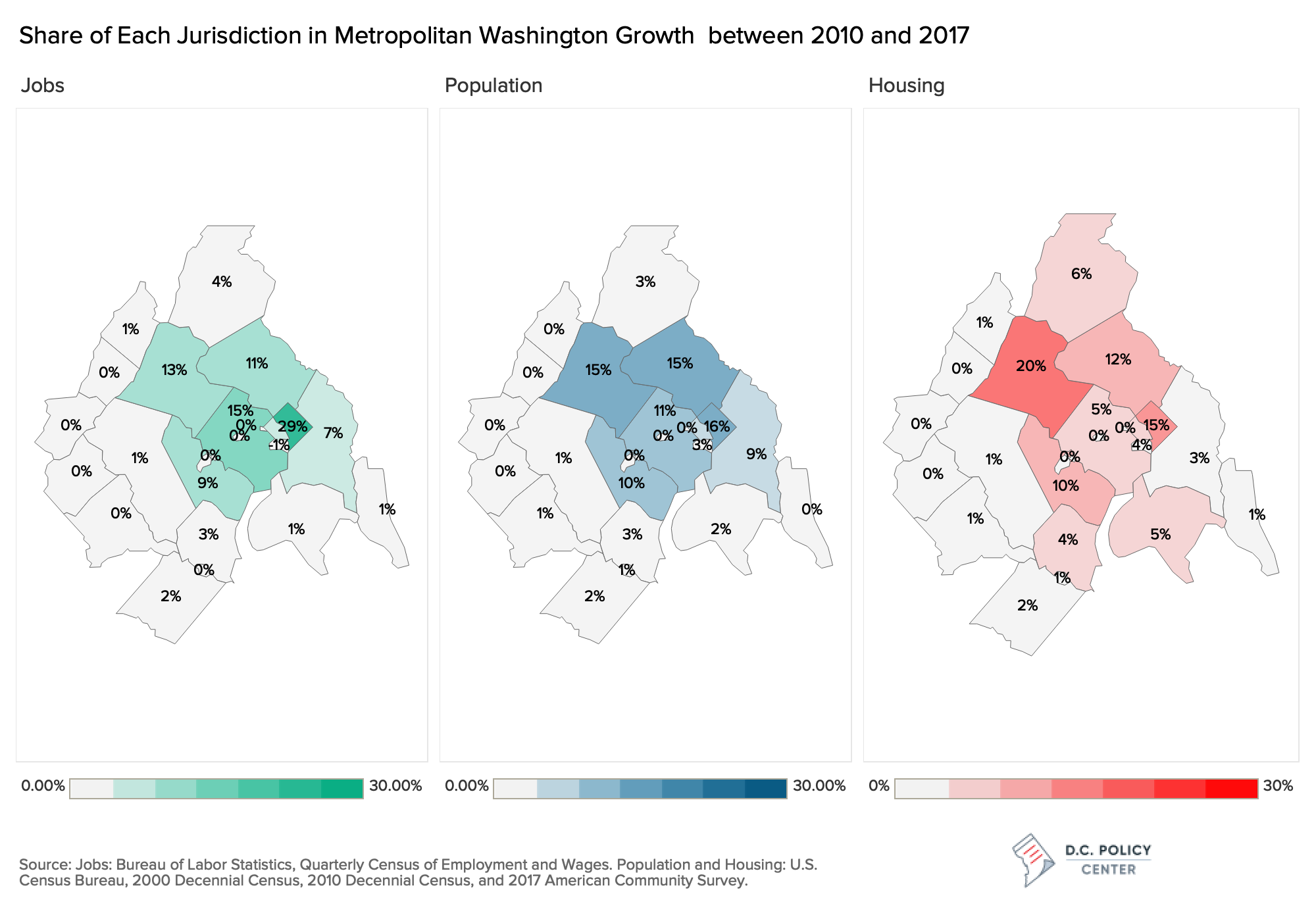

Looking at the job growth since 2010, we see that core counties, as defined by the Urban Institute researchers, accounted for 78 percent of the jobs. But others played a role too: Frederick County added nearly 11,000 jobs (4 percent of all growth), and Prince William County in VA added about 25,000 on net (9 percent of all growth). Stafford and Spotsylvania counties added a combined 15,000 jobs or 5 percent of the growth.

Exurbia played a larger role in accommodating the population growth by adding new housing: Overall, the metro area added 550,771 new residents and 117,536 new housing units (according to the Census Bureau). Exurbia got a larger share of people and housing compared to jobs: the core counties accounted for 74 percent of the population growth and only 67 percent of the housing growth.

That is, the relevant housing market in the metro region includes Prince William and Stafford Counties in VA and Frederick and Charles Counties in MD.

The inclusion of exurbia in Metro growth patterns will not sit well with some urban planners or transportation experts as it means that commuting times are higher for those who settle in parts of the metro region that do not have strong connections to public transportation. Given how the region is growing, we cannot ignore exurbia in the housing (or transportation) discussions. But there is an opportunity cost. More development in under-dense and under-utilized urban sites could have made walkable, transit-oriented infill neighborhoods more affordable and more inclusive.

In measuring the region’s capacity to grow, population-to-housing comparisons could be misleading.

The Urban Institute researchers claim that housing production did not keep pace with population growth. Comparing population to housing units is an easy trap to fall into, but should be avoided given that it is the household count and not the population count that matters in a region’s economy.

Importantly, small changes in household size could make a big difference in the region’s ability to absorb new households. In a thoughtful essay at District Measured (published by the D.C. Office of Revenue Analysis) Stephen Swaim illustrates this point for the District of Columbia (proper, not the region). Depending on what number one uses for household size (2.27 as observed by the 2010 Census, 2.38, observed as the average household size between 2012 and 2016, or 2.93 if we include all occupied housing units regardless of residency of the occupant) the 19,930 multifamily units delivered in DC between 2012 and 2017 could have accommodated anywhere between 78 percent to 100 percent of all new households the city added during the same period.[5]

Similarly, the “housing shortage” estimates provided by COG and used by the Urban Institute researchers are sensitive to jobs-to-housing metric. The COG estimates use 1.54 as the key jobs-to-housing ratio in their forecast. The Urban Institute researchers use—as best as I can tell—a ratio of 1.25 (at least 40,000 housing units for 50,000 jobs). Using the same ratio as COG, they would have added to the “shortage” 32,000 units. Had they used the jobs-to-housing ratio of 1.65, which is what the COG forecast shows for the core counties the Urban researchers focused on in their analysis, their shortage would have been only 30,000 units.

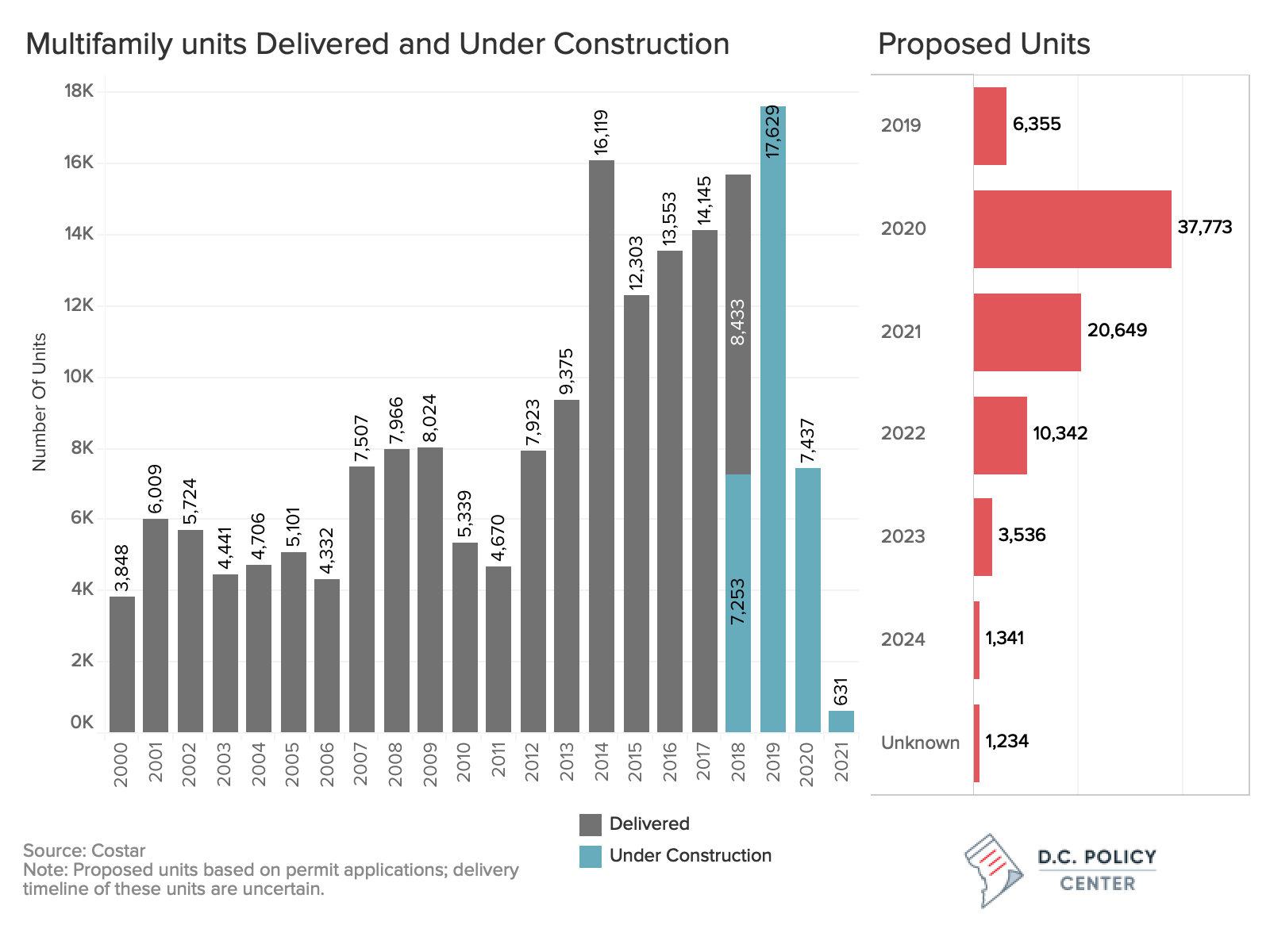

Projecting “housing shortages” using a jobs-to-housing ratio misses a key element of how markets work: households and developers respond to the price signals. Higher prices induce more families to consider alternative housing options, like those in exurbia. Higher prices also induce developers to put more units on the market. As constrained as it is, the Metropolitan Washington area has proved to be incredibly elastic, especially because of the strong activity in multifamily housing. Between 2007 and 2017, multifamily deliveries increased by an annual average of 9,720 units, accounting for 66 percent of growth in housing. In recent years, the growth has been stronger, with an average of 14,000 units since 2014—or three quarters of new housing units created during that period.

What is, then, the housing crisis about?

Rapid price increases in housing already tell us that supply is not growing fast enough, especially in the core parts of the metro region. But why? Every jurisdiction in the region has a slightly different set of reasons but there is a common theme: restrictive land use practices that are designed to preserve rather than grow.

In the District proper, for example, this means that the city looks largely suburban with many residential neighborhoods made up of single family units and few opportunities to expand density. It means resistance to change can be expressed very strongly through existing institutions (zoning, courts, historic preservation, and the Heights Act).

As a result, even with strong growth in multifamily units which has been the biggest source of growth, and the greatest contributor to homeownership, housing prices continue their rapid ascent. Much of this new value capitalizes in existing homes located in parts of the city with little opportunities for redevelopment. Higher mortgage payments and rents exhaust the value created by hard work that could have been otherwise used to improve and enrich lives. Increasing housing burdens push the least fortunate to neighborhoods with few public and private amenities, deepening poverty and economic segregation. And as the jobs, population, and housing maps show, many others move further away increasing the time and money costs of commuting.

Why is Amazon HQ2 important?

All the problems people attribute to Amazon in Seattle or to Google in San Francisco already exist in our region. The housing market is tight, the traffic is already bad, displacement is rampant, and economic segregation is deepening. If Amazon brings its second headquarters here, housing problem may be aggravated, but only marginally. Traffic may get worse, but not much more than what is already projected.

We have lived with a chronic housing problem for too long while policymakers have tiptoed around the underlying cause—impeded development. It is now so bad that we are worried about the implications of a large employer choosing our region as its home.

Amazon HQ2—regardless of the company’s final choice—is important because it brightly shines the light on this very problem, pressing the regional policymakers to look beyond subsidized affordability or marginal changes around zoning when they think about housing.

Ultimately, that is my read of the Urban Institute’s analysis: HQ2, even as a possibility (and better if real), is an opportunity not to be missed in forging a regional vision of what our future might look like. We have the necessary infrastructure: many groups have been working on developing regional solutions to the region’s housing problem: the COG, the Housing Leaders Group of Washington Region, the 2030 Group, and most recently, the Greater Washington Partnership. These groups are moving the ball, but Amazon HQ2 can provide the political will necessary to get it over the goal line.