ONE | THE ROLE OF DISTRICT’S RENTAL HOUSING IN CREATING AFFORDABILITY AND INCLUSION

The high cost of housing in the District of Columbia is a significant challenge. The city’s zoning laws and poorly run regulatory regime, sometimes combined with resistance to growth, restrict the amount, type, and location of housing that can be built. The result has been steep increases in housing prices,[1] and the consequent affordability crisis has made it difficult for households with low and moderate incomes to remain in the city. This has further increased economic and racial segregation in the city, especially for owner-occupied housing.[2] In this context, the city’s rental housing stock—with its lower costs, greater variety of units, and a more equal distribution across the city—offers one avenue for reducing housing burdens and mixing incomes to create affordable and inclusive neighborhoods.

Rental housing’s potential ability to create affordability and economic inclusion is the topic of this study. This report first examines the different price and location options the District’s rental housing is providing in order to gauge its capacity to create affordability. Second, it examines how this capacity matches renters’ income profiles to evaluate the extent to which rental housing is meeting the city’s affordability needs. Third, it examines whether rental housing has created more economically inclusive neighborhoods than owner-occupied housing. Fourth, it presents a new policy tool that can leverage the strengths of the city’s rent-controlled housing stock in order to increase the number of subsidized affordable units in parts of the city where it has been difficult to do so.

Affordability and economic inclusion in the context of D.C.’s rental housing

The District has invested a great amount of public resources in rental housing to ease housing burdens for its lower-income residents. Through interventions in the rental market, the District’s programs—along with federal subsidies—have delivered approximately 52,000 affordable units.[3] These units are “affordable” by policy design: the out-of-pocket rent tenants pay is restricted to 30 percent of their income. This rent depends on the affordability target and household size, but the units only serve households that earn at most 80 percent of the Area Median Income (also called the Median Family Income). Some affordable units are in public housing (about 7,500 units),[4] some are owned by nonprofits that receive public subsidies or preferential tax treatment (or both) from the city, and some are owned by for-profit entities that commit to lowering rents for all or some of their units in return for public financing or additional density.[5] In addition, some tenants receive rent subsidies from the federal government (11,180 vouchers) [6] or the District (approximately 3,200 vouchers), or both, to keep their rents affordable—that is, under 30 percent of their incomes.[7]

Subsidized housing units are an important source of affordability, but at current funding levels, they can serve approximately half of D.C. households that would qualify for public assistance. Of the approximately 287,000 households in the District, an estimated 125,000 households (44 percent) earn less than 80 percent of Area Median Income, and approximately 59,000 households (20 percent) earn less than 30 percent of Area Median Income. Of those that earn less than 80 percent of Area Median Income (the highest income that qualifies for public support), 93,700 households are renters.[8]

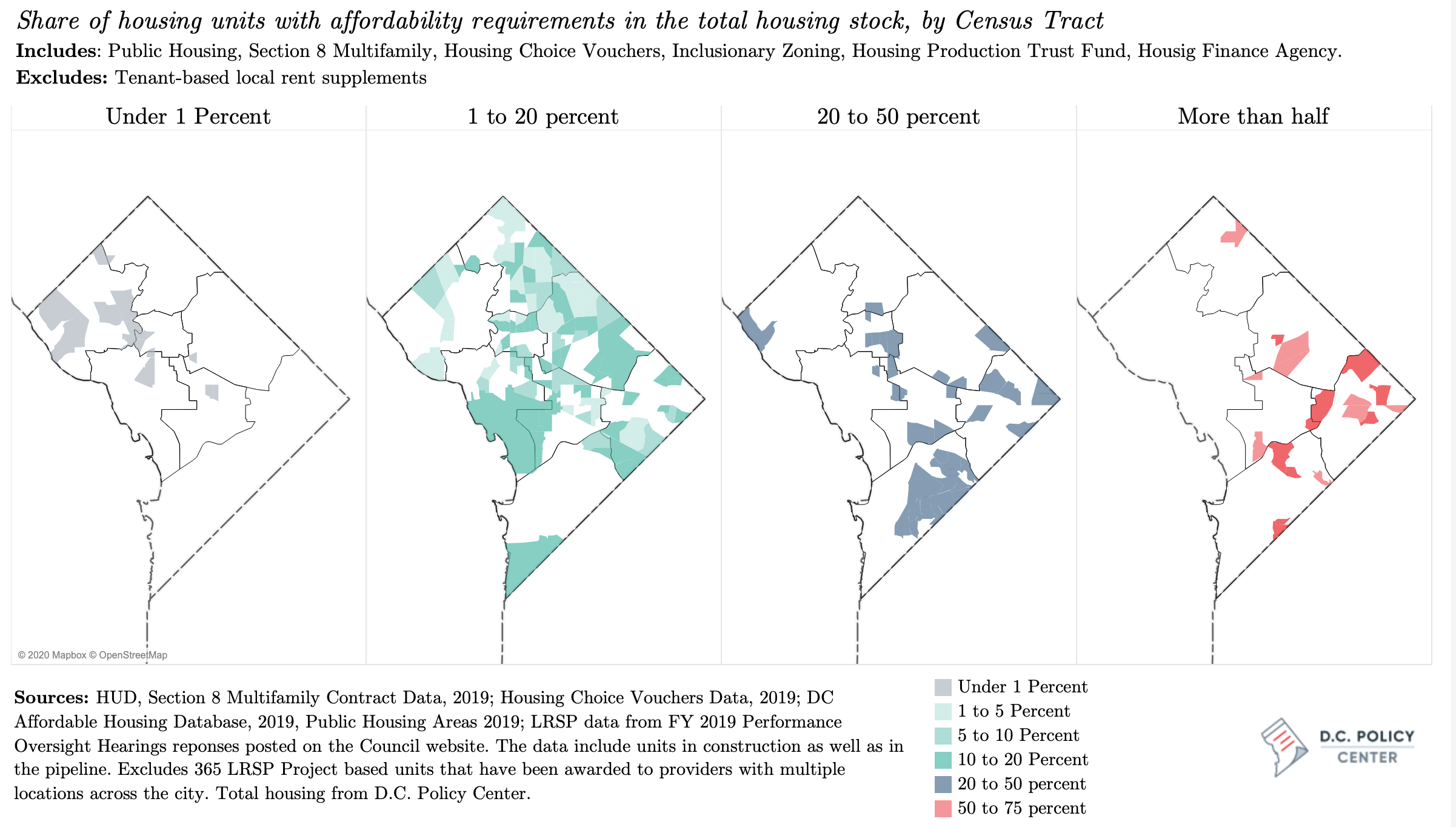

Additionally, publicly subsidized housing tends to be concentrated within certain parts of the city, reducing opportunities for economically inclusive neighborhoods. Half of the city’s subsidized rental units are in Wards 7 and 8—where, as this report will show, both incomes and market rents are already low—and only 1 percent are Ward 3, where incomes and rents are high. As a result, subsidized housing constitutes almost the entire housing stock in some neighborhoods, and is virtually absent in others.[9] Even the city’s Inclusionary Zoning program—which requires new development to set aside a certain share of units as affordable—is limited in its inclusionary capacity by current zoning: more than half of the units produced by the Inclusionary Zoning program are in Wards 5 or 6, where zoning is more permissive; only 11 percent are in Wards 3 and 4 combined, where most land is set aside for only single-family housing.

There is also interest in amending rent control laws to help keep rents lower in rent-controlled units, as the District’s rent control laws are expiring at the end of 2020. This discussion in D.C. follows the “universal rent control” laws enacted in Oregon[12] and New York State, and being debated in Colorado, Illinois, and Washington State: the proposal discussed in the District would strictly cap rent growth to the growth in the Consumer Price Index (at present the District allows for an additional 2 percent growth, CPI+2%), eliminate the provisions that allow for higher increases (vacancy increases and voluntary agreements), and expand rent control laws to newer and smaller buildings [13],[14] The expectation could be that stricter rent control laws—an in turn, lower growth in rents—would increase affordability over time.[15]

The importance of studying rental housing now

Increased interest in local and national policy discussions using the rental stock to increase affordability is motivating this report. The primary goal of this report is to understand how different segments of the rental market—including the rent-controlled stock and shadow rental units—contribute to the affordability of housing and economic inclusion across neighborhoods in the District of Columbia. To this end, this report provides a detailed analysis of all rental units, including building and unit types, unit sizes, and rents. It examines the affordability of and economic inclusion in the rent-controlled stock separately from the rest of the rental apartment market. It also examines the role of shadow rentals, which has been largely neglected in policy discussions,[16] but fill an important gap in the District. The report also examines the sources of growth in the rental market as well as types of drain—that is, ways in which units are taken out of the rental stock, including the rent-controlled stock.

The secondary goal for this report is to explore policy options that could repurpose existing rental apartment units, specifically within the rent-controlled stock, to increase affordability and economic inclusion in the District. This is also timely. The Bowser administration’s neighborhood-specific goals signal a forceful commitment to economic inclusion, but to realize them, D.C. needs new policy tools. For instance, in neighborhoods west of Rock Creek Park, the administration’s plan calls for 1,260 new housing units, and 1,910 new affordable homes. This means the affordable housing goals can only be met by converting existing non-subsidized stock into affordable units.[17]

This report provides a new policy option, “Inclusionary Conversions,” that has the potential to create long-term subsidized affordable units in the District’s rent-controlled apartment buildings in return for either annual subsidies similar to local rent supplements, or one-time capital infusions similar to the refinancing or rehabilitation loans from the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF). This could be achieved at a fraction of the cost of producing new housing units, expanding the capacity of public subsidies in creating affordability, while also committing the landlords of rent-controlled units to keep their apartment buildings in service, and in good repair.

This study uses a broad definition of rental housing. This definition includes both multi-family rental apartments and what is commonly referred to as the “shadow rental market,” which includes rental units outside of multi-family rental apartment buildings, such as single-family homes, condominiums, and flats let by their owners. This is often called the shadow rental market not because it is illegal, but because the transactions are often less regulated, and sometimes, less formal. The report analyzes these two sources separately, but also shows how they complement each other in meeting the demand from the city’s renter households.

What are the main takeaways from this study?

The report provides extensive details on rental housing, rents, affordability, and inclusion. Below are what we consider to be the most important takeaways:

On rental housing characteristics:

- Rental housing in the District of Columbia extends well beyond rental apartment buildings. 64 percent of the District’s 322,000 housing units are potentially available for rent; of these only 124,600 are in rental apartment buildings, as classified by the city’s tax administrators. Single-family homes, condominiums, flats, and units in various types of conversions make up about a third of the District’s rental housing.

- Because the shadow rental market is such a large share of the stock, rental housing is fluid. Owners of single-family homes or condominiums frequently put in and pull out their units from the rental market.

- An estimated 72,900 rental apartments are in buildings under rent control. This represents at least a 15 percent—and potentially up to 30 percent—loss in the number of rent-controlled apartments since the city enacted the Rental Housing Act of 1985.

On rents and affordability:

- Rent-controlled units offer deep savings, especially in parts of the city where housing values have increased rapidly.

- For those seeking a rental apartment, there is a lot of pressure from the bottom and a lot of pressure from the top. There are 40,000 households who cannot pay more than $750 per month in rents to keep housing expenditures below 30 percent of their incomes, but there are fewer than 800 units in this price range. There are also over 41,000 renter households who could pay north of $2,700 per month without being burdened, but only 14,000 units of that level of rent. These households, both poor and rich, compete for rental units.

- The shadow rental market helps relieve these pressures on rental apartments by offering a great variety of housing at a great variety of price points. Shadow rental studios and one-bedrooms have lower rents than rental apartments, and even the rent-controlled units, and thereby easing the pressure from the bottom. Larger units in the shadow rental market do not always have lower rents, but there is a lot of them meeting the demand from larger or wealthier households, and thereby easing the pressure from the top.

On inclusion and displacement:

- Renters in rental apartment buildings are also economically segregated, with the highest income renters living in parts of the city with higher rents, and lowest income renters living in parts of the city with lower rents. The estimated rent burdens are more evenly spread across the city and within wards for the shadow rental market.

- The presence of rent-controlled units in a neighborhood appears to mitigate displacement. A larger share of residents stays in place in census tracts where rent-controlled-units are a larger share of the housing stock, but no such relationship exists when measured for all rentals or for owner-occupied housing. Similarly, a strong presence of rent-controlled stock is correlated with a smaller loss in minority populations.

On the potential to increase affordability and economic inclusion:

- An important characteristic of the rent-controlled housing is that rent-controlled units are everywhere, especially in parts of the city where building affordable units has been difficult. Another important characteristic is that their rents are lower, as rent control laws have, over time, created a sizeable difference in rents of rent-controlled and uncontrolled units.

- We propose an Inclusionary Conversion tool that takes advantage of the relatively low rents and ubiquity of the rent-controlled stock. Under this approach, the District would convert a portion of existing rent-controlled units into designated affordable units with covenants. Once the conversion takes place, the converted unit would operate in the same way as an Inclusionary Zoning unit: its rents would be capped at the desired affordability target for the duration of the covenants, and the unit would be made available only for income-eligible tenants. In return, the landlord would receive financing support from the District that is the equivalent of the difference between the rent-controlled rent and the capped-rent.

- The District can finance Inclusionary Conversions with a one-time cash infusion, similar to a Housing Production Trust Fund loan, or with annual operating subsidies similar to the Local Rent Supplement Program. If funded as an annual subsidy, the support for each unit would be equivalent to the difference between the prevailing rent and the maximum rent the landlord can charge. If funded as a one-time cash infusion, the support would be equivalent to the present value of the annual operating subsidy over the lifetime of the covenants and can potentially be incorporated during a capital event such as refinancing.

- Because of where rent-controlled units are, the highest number of Inclusionary Conversion units can be in parts of the city where existing affordable housing programs have not been successful.

- And, because the model relies on financing the gap between a subsidized unit and the lower rents in rent-controlled buildings, Inclusionary Conversions would require a much smaller public subsidy than needed under current affordability programs.

The report is organized in the following way: Chapter two provides detailed information on rental housing including the number, type and location of units for rental apartments, the rent-controlled stock, and the shadow rental market. Chapter three evaluates the ability of the rental housing stock to meet the affordability needs in the city. Chapter four evaluates whether rental housing—and specifically rent-controlled units—in the District has been a source of economic inclusion, and whether rent-controlled units have helped tame displacement. Chapter five presents the Inclusionary Conversion tool that utilizes the District’s existing rental stock to create affordability and inclusion through public subsidies. Chapter six provides conclusions and additional considerations for policymakers.

You’ve reached the end of Chapter 1.

<< Back: Executive Summary | Next: Chapter 2 >>

Or return to the main publication page.

Notes

[1] Nominal housing prices (purchase only) have increased by over five times since 1991 in the District of Columbia. The growth in the metropolitan Washington area has also been fast, but not as fast as the District. In the metropolitan area, housing prices increased three times since 1991. This information is from the Federal Housing Finance Agency, Quarterly Data on Purchase-Only Indexes for the District of Columbia and Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area.

[2] For details, please refer to the analyses in Yesim Sayin Taylor, “Taking Stock of District’s Housing Stock” (Washington DC, 2018).

[3] The recent Housing Equity report published by the Office of Planning and the Department of Housing and Community Development identifies 51,900 housing units, including about 6,000 units that are under construction or in the pipeline. This number does not include tenant-based vouchers. See District of Columbia Office of Planning and Department of Housing and Community Development, “Housing Equity Report: Creating Goals for Areas of Our City” (Washington DC, 2019).

[4] Based on information published in the District’s Open Data Portal on May 17, 2018. Available under the name Public Housing Areas.

[5] Through the Housing Production Trust Fund and Inclusionary Zoning (and in combination with supports from the Housing Finance Agency and sometimes with federal programs like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credits), the District has added 9,907 new units with affordability covenants since 2015; another 3,993 are under construction, and over 6,000 are in the pipeline. This information is gleaned from the Affordable Housing Dataset dated October 21, 2019, available at Opendata.dc.gov.

[6] Based on information published by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for 2019.

[7] Based on information submitted by the D.C. Housing Authority to the D.C. Council’s Committee on Housing and Community Development in response to 2019 agency performance review questions and published by the D.C. Council.

[8] Most of these households (an estimated 81,000) are small with one or two persons. An estimated 11,750 households with four or more persons (about 41 percent of 34,100 such households) are potentially eligible for subsidized housing. While this is only 11 percent of low-income households, it is by no means trivial. We do not know if all subsidized housing programs prioritize families over smaller households, but we know that larger households are more likely to live under unfavorable conditions: 57 percent of renter households with four or more persons are cost burdened or live in over-crowded homes without adequate facilities, while the similar share for households with one or two persons is 49 percent. This information is based on the tabulation of 2017 American Community Survey data by the Economic and Market Analysis Division at HUD.

[9]Additionally, there are 22 tracts where there is no publicly subsidized housing, but some of these tracts have very few housing units.

[10] According to CoStar, the city has added, on average, 4,700 units per year in the last five years.

[11] Yesim Sayin Taylor, “Land Value Tax: Can It Work in the District?” (D.C. Policy Center, 2019).

[12] Oregon’s universal rent control legislation caps the rents at CPI + 7%. For 2019, this number was 10.3 percent.

[13] Ally Schweitzer, “Here’s What Rent Control Could Mean For D.C.’s Housing Crisis,” WAMU, 2019, Natasha Lennard, “Progressives Push for Universal Rent Control in New York,” The Intercept, 2019,; Steven Wishnia, “Your Guide To Which Universal Rent Control Measures Will Survive Albany,” Gothamist, April 24, 2019.

[14] The proposal advocated by the “Reclaim Rent Control” platform would: (i) cap annual rent increases at the rate of inflation, instead of the current rate of inflation + 2%; (ii) expand rent control laws to smaller buildings and landlords who own just four housing units; (iii) lower the minimum rate of return on rent-controlled buildings from 12% to 5%; (iv) expand rent control to buildings built before 2005, and subject all units subject to rent control once they are 15 years old; (v) eliminate vacancy increases; (vi) eliminate voluntary agreements; and (vii) ensure that rent increases for capital improvements are temporary. As of the drafting of this paper, the proposal had not yet been turned into a bill.

[15] Research across the country (reviewed in Appendix II of this report) shows that restrictive rent control policies can also lead to a decay in both the quality and the quantity of units, and significantly dampen housing values, and consequently, tax revenue.

[16] Konstantin A Kholodilin et al., “Social Policy or Crowding-out? Tenant Protection in Comparative Long-Run Perspective,” (National Research University Higher School of Economics, Basic Research Program Working Papers, 2019).

[17] The Housing Equity Report identifies “conversion” as a means of repurposing the existing stock but does not provide any further detail.