At least 67,000 D.C. residents—about 10 percent of the population[1]—are estimated to have a criminal conviction record, [2] and approximately 2,800 are released from incarceration annually. Even after these returning citizens are released from prison,[3] however, the consequences of their crimes continue. These former offenders continue to face hardships and challenges upon release, including finding housing, financial support, and jobs because of their time in prison. These hardships are often referred to as collateral consequences, and can make reentry extremely difficult for someone involved in the criminal justice system. As Bruce Ormond Grant has discussed previously, the complex nature of D.C.’s criminal justice system makes reentry even more difficult, as many D.C. residents serve time at federal prisons around the country far away from family and support systems.

D.C. residents who have been released from prison and who are on parole, probation, or supervised release are supervised by the Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency (CSOSA), which helps its clients obtain housing, receive mental health and substance abuse treatment, and gain employment. As a Graduate Fellow at CSOSA from September 2017 to May 2018, I conducted a study to investigate the barriers that returning citizens face when they seek employment.

As part of my research, I spoke with CSOSA staff, employers who hire returning citizens, program specialists, and researchers to learn more about the hardships that returning citizens face upon release, and what can be done to help improve their economic outcomes. I also analyzed case data from CSOSA’s Office of Research and Evaluation that showed how employment outcomes varied by individual characteristics such as age, housing status, type of crime conviction, etc. The research aimed to discover:

- What is working for CSOSA clients who are able obtain employment, and what areas could be improved upon?

- How do individual factors—such as supervision type, age, or location—relate to success post-incarceration?

- What do local leaders and experts in criminal justice and reentry believe to be the biggest obstacles facing D.C. returning citizens?

Who are CSOSA’s clients?

As of March 2018, CSOSA was responsible for 9,924 clients, all of whom are D.C. residents who have been released from prison and who are on parole, probation, or supervised release. Among CSOSA’s clients, 72 percent were considered “employable”—meaning they are not retired, disabled, suffering from a debilitating medical condition, receiving Supplemental Security Income, participating in a residential treatment program, incarcerated, or participating in a school or training program. CSOSA’s “employable” clients are the focus of the analysis in this article.

Among CSOSA’s clients, as of March 2018:

- About 89 percent are black, compared with about half of the general D.C. population; Hispanic and white clients each make up about 5 percent of CSOSA’s client population.

- About 86 percent of clients are male.

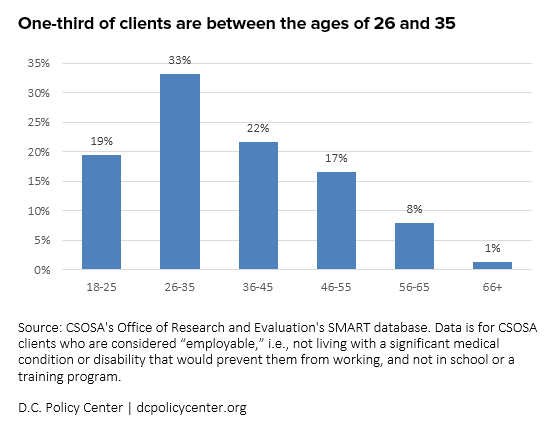

- Half (50 percent) are under the age of 35; only 2 percent are over the age of 65.

- 36 percent of clients have symptoms of mental illness either previously documented or recorded during the intake process.

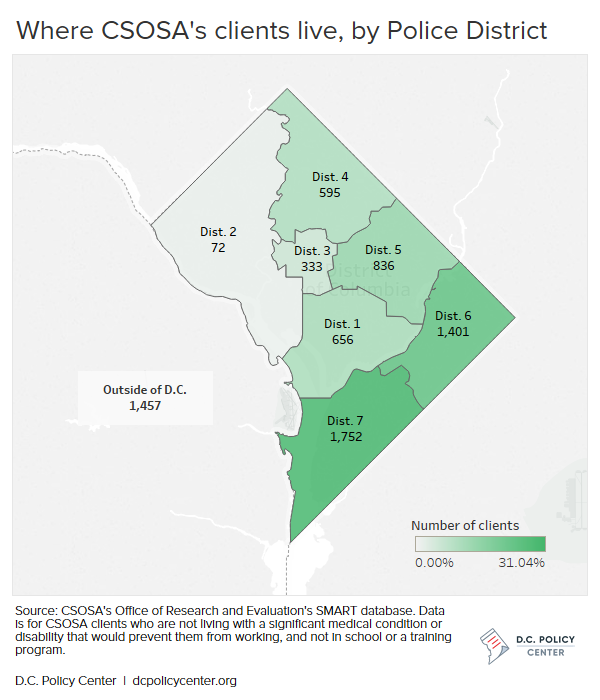

- Geographically, Police District 7—which roughly corresponds with Ward 8—was home to the largest share of clients (about 20 percent). About 19 percent live outside D.C. in surrounding states such as Virginia and Maryland.

Overall, 42 percent of these clients were employed, 43 percent were unemployed, and 15 percent had their employment status listed as “unknown.”

What factors are associated with higher employment rates?

By examining case data from CSOSA’s Office of Research and Evaluation, I was able to observe how employment rates varied with several individual factors, such as housing status, supervision type and level, and type of charge. Below, I explore how each of these factors in greater detail.

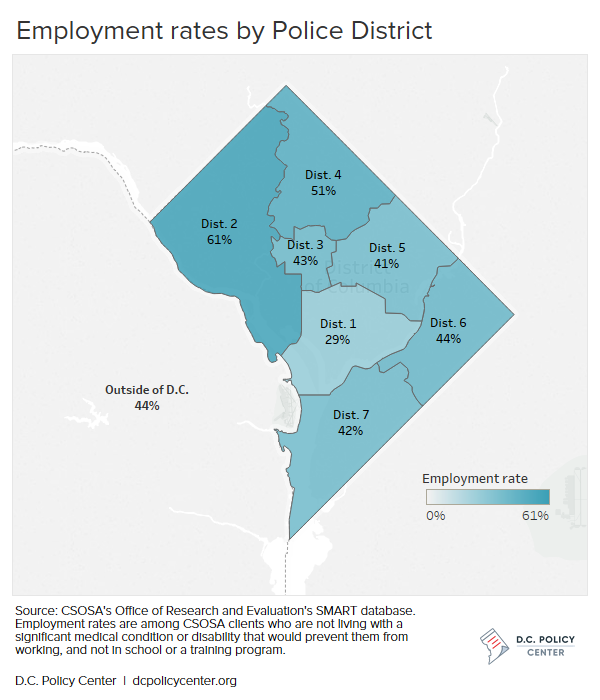

CSOSA client employment rates vary widely across D.C.

Rates of employment vary for CSOSA’s clients depending on where they live in D.C., in patterns that echo existing inequalities throughout the city. For example, while only one percent of CSOSA’s clients live in Police District 2 (the western portion of the city), 61 percent of those in that district are employed; the employment rate is 29 percent employment rate in Police District 1, where about 10 percent CSOSA’s clients live.

The largest proportion of CSOSA’s clients—about 25 percent—live in Police District 7, where the employment rate is 42 percent. Among the 19 percent of CSOSA’s clients who live outside D.C., the employment rate is about 44 percent.

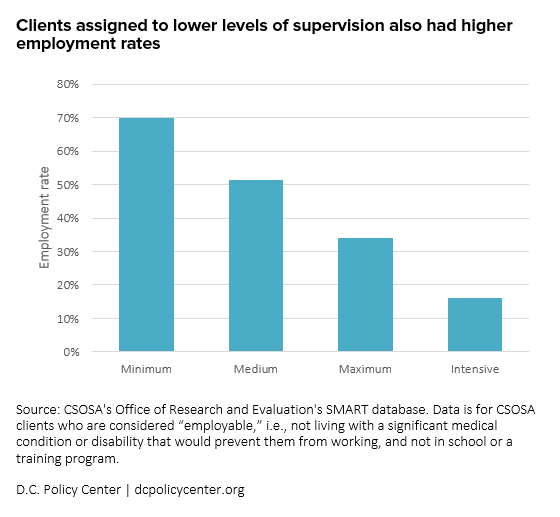

Returning citizens who are assigned the least intensive levels of supervision also have the highest employment rates.

One of the most striking contrasts I saw on the rate of employment was by their assigned level of supervision. When a client first comes to CSOSA upon release from prison or from the D.C. Court System, they undergo a screening to determine their level of supervision needed. The screening tool, known as the AUTO Screener, is an “intelligent” risk and needs assessment tool that produces supervision plan recommendations based on information about a client’s background and answers to a series of questions.[4] Clients will then be assigned to one of four categories of supervision—intensive, maximum, medium, and minimum—based on the decision of CSOSA’s Community Supervision Team.

Clients will then be assigned to one of four categories of supervision—intensive, maximum, medium, and minimum—based on the decision of CSOSA’s Community Supervision Team’s decision. In general, clients placed under higher levels of supervision also had lower employment rates, as intensive supervision clients had jobs 16 percent of the time and minimum supervision clients had jobs 70 percent of the time. A further avenue of research for CSOSA would be to study whether supervision levels actually affect employment, or whether it is simply the case that the same characteristics that influence clients’ employment rates also affect their supervision assignments.

Employment rates varied dramatically depending on charge and supervision type.

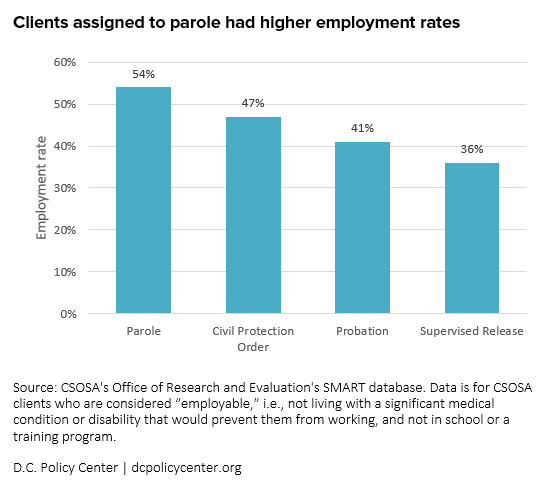

In addition to general supervision levels, CSOSA places clients under one of five forms of supervision: probation, parole, supervised release, deferred sentence agreement, and civil protection order. (Deferred sentence agreement will be considered part of probation for this analysis.) Of the five supervision types, those assigned to parole (54 percent) had the highest employment rates, and those on supervised release had the lowest employment rate (36 percent).

Many clients are relatively new to CSOSA, as about a third had been under supervision for six months or less. About three-quarters (76 percent) of younger clients ages 18-25 are on probation, a higher rate than other age groups. Generally, among those under supervision, employment rates are higher for those who have been out of prison the longest.

In terms of the type of charge, 48 percent of clients who have sex crime convictions are able to find jobs, along with 38 percent of those with firearm charges and 23 percent of those convicted of drug crimes. Interestingly, within different types of charges, lower supervision levels did not always correspond with higher employment rates: Only about 12 percent of clients who were charged with a drug crime and were on probation were employed, for example. More research is needed to see if there are other factors that could explain these differences, such as severity of offense or the age of the offender.

Housing and employment

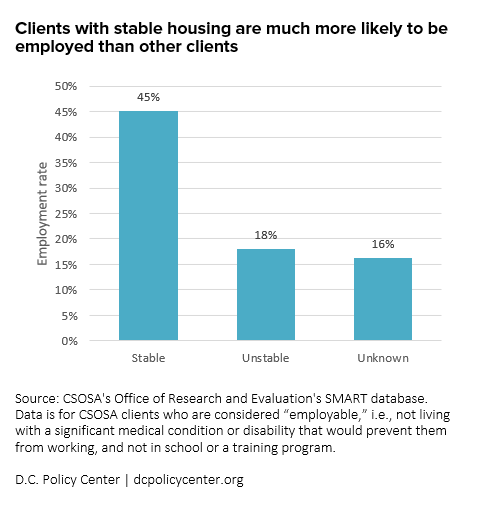

Housing has become increasingly unaffordable for D.C.’s low-income residents, and renters with felony convictions are often ineligible for many subsidized housing options. Returning citizens with stable housing[5] were employed at a rate of 45 percent, while those without stable housing, such as those in homeless shelters or no fixed address, only were employed at a rate of 18 percent.

Many of the employers I spoke with mentioned how difficult it was for their homeless workers to both find and keep employment. It would be difficult for them to concentrate on working when they did not know where they were going to sleep that night, and it was an issue not being able to have an address to put down on job applications.

What are the most commonly cited barriers to employment?

For the qualitative portion of my study, I interviewed employers, officials, and experts on returning citizen affairs and identified the most commonly-cited factors that were discussed. The most prominent of these were criminal background checks and legal barriers;

Criminal background checks

Almost every interviewee mentioned background checks are a significant roadblock to stable employment. In 2014, D.C. passed the Fair Criminal Record Screening Act, a “Ban the Box” initiative that prohibits employers in the District from inquiring about job applicants’ arrest record, charges, or convictions prior to a conditional offer of employment. However, many interviewees said that employers still conduct background checks that disqualify many applicants. In addition to violating D.C. law, these background checks are especially harmful because they are usually very broad, and only check to see if there was an arrest—without considering if there was a conviction or if the crime is related to the job in any way.

The Criminal Record Screening Act says that employer can only withdraw a conditional offer of employment after considering the factors surrounding the applicant’s conviction, such as whether the offense is relevant to the duties of the job, and may only withdraw the offer if that decision is based on legitimate business reasons. However, in practice, employers may not be taking such a nuanced view into account.

Tony Lewis, a vocational specialist at CSOSA who helps returning citizens find jobs, called one of his recent clients during our interview to discuss how this issue affected him. The client explained that even though he had done everything in his power to get a job, including taking multiple job training and readiness classes, the fact that he had a criminal record barred him from getting an offer. “The background check is so discouraging,” Tony explained. “Clients will get the job offer and get so excited, only to have it rejected a few weeks later when the background check comes back.” Tony and many other interviewees explained how clients get frustrated by the inability to find a job and begin finding any way to provide for their family they can, even if it means turning (or returning) to illegal activities.

Soft skills

Many interviewees, especially employers, mentioned that they had encountered clients who did not know how to create a resume, prepare for a job interview, or handle the stress of a new job. The Human Resources lead of a local construction company in D.C. said that lack of basic job readiness is one of the biggest barriers that he sees returning citizens face when seeking employment.

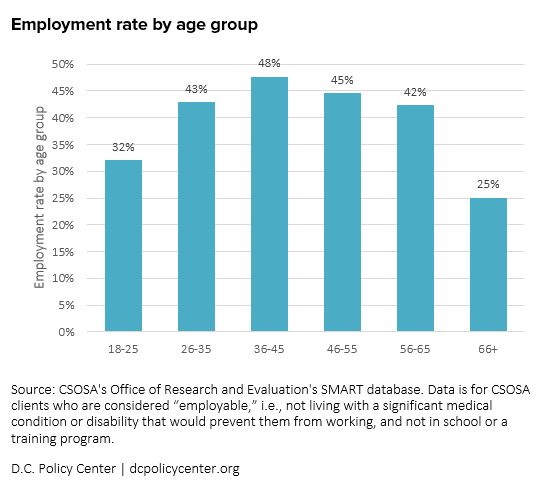

The challenges of developing these types of “soft skills” were especially difficult for young men and women who entered prison before they had built any job experience, and were poorly served from inadequate job readiness training in prison. Overall, 18-25 year-old clients (as well as those 66 and older) had lower employment rates than other age groups.

Trauma and mental health issues

Trauma, in general, was a recurring theme throughout my interviews. Some 36 percent of CSOSA clients have symptoms of mental illness (either previously documented or recorded during the intake process); constant exposure to violence—such as living in a neighborhood where gunshots are commonplace—can also contribute to chronic trauma. Many interviewees described that those who had unresolved trauma, caused before they entered prison or from the prison experience itself, lacked the processing or coping skills needed to be a good employee. As a result, these clients were often unable to work through to common workplace stressors—such as making a mistake or having a disagreement with a client or colleagues—and would react inappropriately or quit.

Several interviewees discussed how trauma and mental health issues largely go untreated among returning citizens due to many factors, including stigma within their communities and lack of mental health resources. Mental health care can be deemed necessary in a client’s supervision plan, but finding and accessing quality care is another challenge. CSOSA staff described clients waiting hours to get any kind of treatment at the mental health center, as well as a lack of empathy and care from mental health professionals. One employer, Joe Andronaco of Access Green, is developing a system to re-train trauma-affected returning citizen employees on how to think and process information, which he believes will lead to better decision making and longer employment.

Lack of training and education

Many of D.C.’s returning citizens lack formal education beyond high school, and this has proven to be a challenge in D.C.’s competitive job market. A caseworker from D.C.’s Mayor’s Office for Returning Citizens’ Affairs mentioned only five of his 98 clients had any college experience. Another official said that the typical education opportunities inside prisons are focused on getting participants to earn their G.E.D., without thinking of continuing on.

Before CSOSA and D.C.’s prison system came under federal control in 1998, D.C. offenders were incarcerated in Virginia and were able to take classes with the University of D.C. No such system is offered now. And even when the prisons holding D.C. residents, which are located around the country, do offer skills classes, the skills taught may not be relevant to D.C.’s job market. For example, a furniture upholstery class at a prison in North Carolina may not prepare returning citizens for the job market in D.C.

Legal barriers

Returning citizens may face other issues that are not directly related to their criminal convictions, but still may be exacerbated by them. One example of this is debts owed to the city. In part due to persistent employer biases against hiring returning citizens, the D.C. government encourages returning citizens to create their own business opportunities through entrepreneurial training programs such as Aspire to Entrepreneurship[6]. However, D.C.’s “Clean Hands Law” states that anyone who owes more than $100 to the District government cannot apply for a license or permit, and is ineligible for city contracts. This even includes unpaid parking tickets and other fines, which can be a significant issue for returning citizens who have not been able to obtain regular employment.

Limitations and next steps for research

As a graduate student with a fixed time frame for this study, I did face limitations in my research which could be expanded upon in future work. First, I was limited in my access to data from CSOSA due to my status as an independent contractor, instead of a full-time employee. As such, as I was only able to run crosstabs of aggregate data. Those within CSOSA with full access to case files could expand upon my research by running regressions on the factors discussed in this article.

Additionally, I was not able to complete randomized interviews due to time and access restrictions; I interviewed those I was able to gain access to during my tenure at CSOSA. Further research could draw from a more comprehensive and varied set of employers and experts, as well as returning citizens themselves, to reduce the potential for selection biases. Randomized surveys could also help quantify employer attitudes and knowledge, which would be particularly useful for further research analyzing the lack of use of D.C.’s legal liability provisions. Further research could confirm the rates at which the federal bonding and tax credit programs is used, as well as what is preventing employers from using these programs.

Another area for future research is retention. Retention is not consistently measured at CSOSA, so it can be difficult to determine how successful their job programs are in the long run. However, interviewees pointed out that many of the same factors that prevent returning citizens from finding a job can make it harder for them to keep it. For instance, those who did not have stable housing oftentimes were unable to keep their job as they were focused on finding a place to sleep at night; others had issues finding transportation to job sites far away or paying for required clothes, boots, or other materials.

Recommendations

There are several areas that CSOSA and D.C. can focus on in order to help their returning citizens find employment success—an outcome that not only benefits those individuals, but strengthens their neighborhoods and the District as a whole.

First, CSOSA should focus on measuring retention in order to capture the long-term success of its programs. It should also focus on populations with lower employment rates, such as those who were incarcerated for drug charges, those assigned to intensive and maximum supervision levels, and those with housing instability. The D.C. government should also consider hiring an ombudsman-type role or providing CSOSA additional resources to work with local businesses in the community to reduce the stigma that a criminal record brings. Pennsylvania has a coalition of state and local agencies which support the successful transition of ex-offenders into the workforce, which could be a model for the District and the surrounding metro area. D.C. and federal government agencies, such as CSOSA and the Bureau of Prisons, would also benefit by doing an assessment of the educational and training programs provided to inmates in federal prisons and how well they match up with D.C.’s economy.

Additionally, CSOSA should assess their current methods of recording and analyzing data to determine why approximately 15 percent of clients have an “unknown” employment status, as this could impact the results discussed in this study. The District should also evaluate the current mental health programs offered to prisoners and returning citizens, as untreated substance abuse, trauma, and mental health issues continue to hinder the success of returning citizens across the city. Finally, the District should create a plan to reduce barriers to public housing and increase housing opportunities and access for returning citizens.

After extensively researching the barriers that returning citizens face to finding a job and stabilizing their lives, I am amazed at every success story I hear of a CSOSA client who has found gainful employment or created a business. The current legal barriers, social stigma, and lack of services available to those with a criminal background create seemingly endless hurdles for economic stability. These hardships often result in homelessness, substance abuse, and mental health issues, as well as recidivism and a return to incarceration. If we truly believe that someone has served their time when their sentence is over, we need to create policies and procedures that help to ensure returning citizens truly get a second (or first) chance at success.

About the data

This article is adapted from the author’s capstone research project, “Breaking Down Barriers: Exploring Solutions to Obtaining and Retaining Employment for Returning Citizens in Our Nation’s Capital,” which won the Philip J. Rutledge Award for Outstanding Capstone Achievement.

The case data in this article is from CSOSA’s Office of Research and Evaluation’s SMART database. Due to extensive federal privacy laws affecting CSOSA as a federal entity, the author was unable to have direct access to the raw data in the form of client case files. Instead, the author worked with research staff within CSOSA’s Office of Research and Evaluation to request cross-tabs of existing data which looked at specific variables of CSOSAs clients that may influence employment. The variables studied were: Supervision Type; Employment Status; Police District; Gender; Age Group; Housing; Supervision Level; Charges (violent, sex, firearm, and drug); Time on Supervision to Date; and Mental Health Status.

The SMART database included records for 9,924 clients. Of these, 72 percent (7,165) were considered “employable” by CSOSA, meaning free from any condition which prohibits them from working. Of these, 41.7 percent were employed (2,990), 43.4 percent were unemployed (3,112), and 14.8 percent had an unknown employment status (1,063). Results are current as of March 5, 2018.

The qualitative data in this article is from 19 semi-structured interviews the author conducted with program specialists, employers, and policy experts.

Robin Selwitz is a recent MPA graduate from Baruch College’s Austin W. Marxe School of Public and International Affairs. She completed the National Urban Fellows program, which develops and promotes diverse leaders in the public and nonprofit sectors, in July of 2018.