In 1867, the federal government purchased a 375-acre site in Anacostia, later known as Hillsdale, and as Barry’s or Barry Farm (more recently as Barry Farms) for the settlement of African Americans after the Civil War. The isolated community was self-contained by design, requiring residents not only to demand the installation of basic utilities, but to lead the way in building schools, churches, and civic organizations. Founded the same year that African American men gained the vote in D.C., Barry Farm and the surrounding area were the home base of an emergent black political class, including Frederick Douglass.[1] The community’s formative years coincided with a period in which black leaders and voters played a significant role in the city’s governance, leading Congress to end home rule in 1874.[2]

As white hostility toward African American participation in civic life increased in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Barry Farm community survived and thrived. While its distance from downtown D.C. contributed to municipal neglect, the area’s physical remoteness from the rest of the city also fostered economic self-reliance via the continued growth of churches, benevolent and literary societies, entrepreneurship, and an independent press.[3] This section of Anacostia flourished as the home of political and religious leaders, scholars and educators, business owners, and civic activists.[4]

In 1941, the government seized a 34-acre section of the community’s land for the construction of Barry Farm Dwellings, a public housing development for African Americans. (Public housing was segregated until the 1950s.) The complex was designed to foster family life and community engagement, and became a hub of activism in the 1950s and 60s. Residents waged a legal campaign resulting in the desegregation of D.C. public schools; helped found the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO); and received national attention for youth organizing. They were also central to D.C.’s 1980s go-go scene.

* * *

A freedmen’s village at Barry Farm

Barry Farm takes its name from an estate once owned by Washington City merchant and councilman James Barry, who had purchased this section of the “St. Elizabeths” tract in hopes of profiting as the city expanded eastward. However, the tract remained isolated from the rest of city in 1867, when the federal Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) began searching for sites to house the 40,000 refugees from slavery who had arrived in D.C. during the Civil War (1861-1865). After white resistance prevented the Bureau from purchasing land west of the Anacostia near the Navy Yard, officials secretly negotiated to buy 375 acres from Barry’s heirs in early 1868. The site was hilly, densely forested and filled with underbrush. Black laborers cleared the land and cut roads.[5]

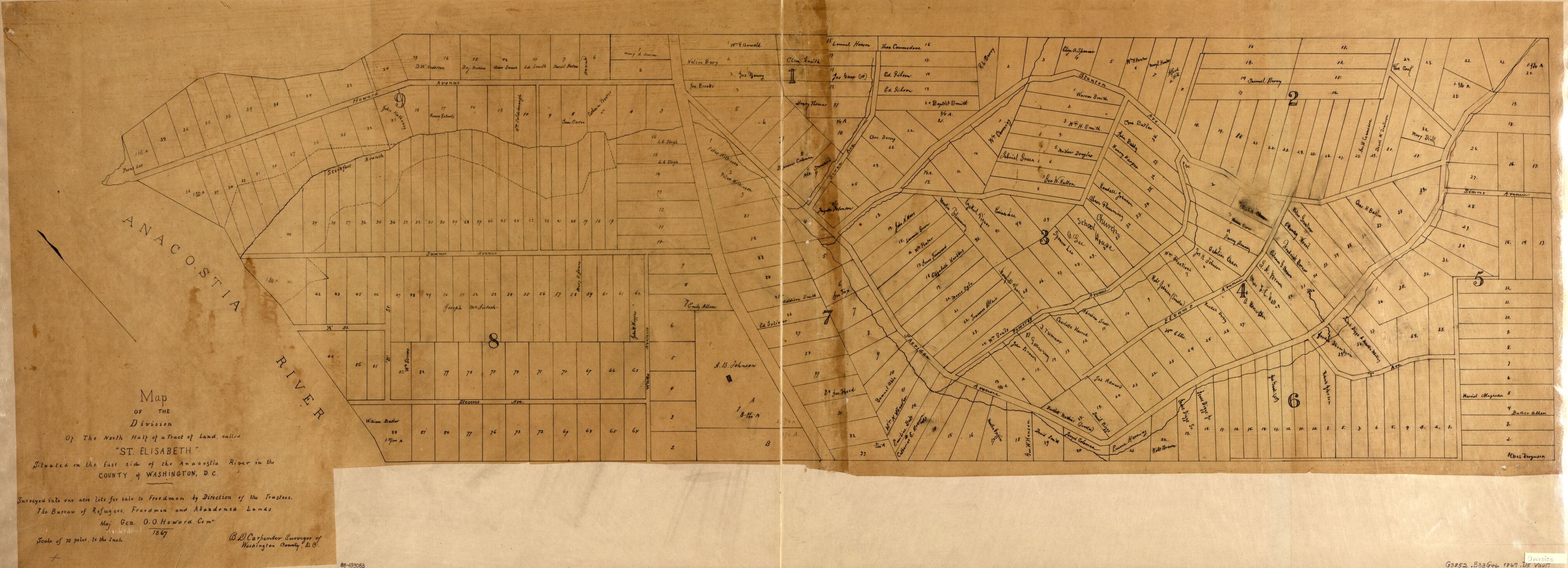

Map of St. Elizabeths tract in 1867. “Map of the division of the north half of a tract of land called ‘St. Elisabeth,’ situated on the east side of the Anacostia River in the county of Washington, D.C.” United States. United States Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1867. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Map of St. Elizabeths tract in 1867. “Map of the division of the north half of a tract of land called ‘St. Elisabeth,’ situated on the east side of the Anacostia River in the county of Washington, D.C.” United States. United States Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1867. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

By October 1868, most of Barry Farm’s 359 one-acre lots were already sold, along with enough lumber and supplies for each family to build a two-room house. Within two years of its establishment, 266 families had moved to the site. As described by historian Louise Daniel Hutchinson, many families made their way to Anacostia after working downtown all day, and built homes by candlelight. However because “many whites did not want to see a community of black landholders established,” she wrote, “some blacks lost their jobs, while others were attacked en route to their new homes.”[6] The growing community banded together to further clear the land and to cultivate gardens and livestock. Barry Farm’s widely spaced streets were named for anti-slavery legislators Thaddeus Stevens (PA), Charles Sumner (MA) and Benjamin Wade (OH), as well as Freedmen’s Bureau officials John Eaton and Oliver O. Howard, among others. Its large lots provided substantial space for growing vegetables and fruit trees. Residents immediately began fundraising for a school, and with the Bureau’s help, soon purchased land and built one. African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and Baptist churches were established during the settlement’s first two years.[7]

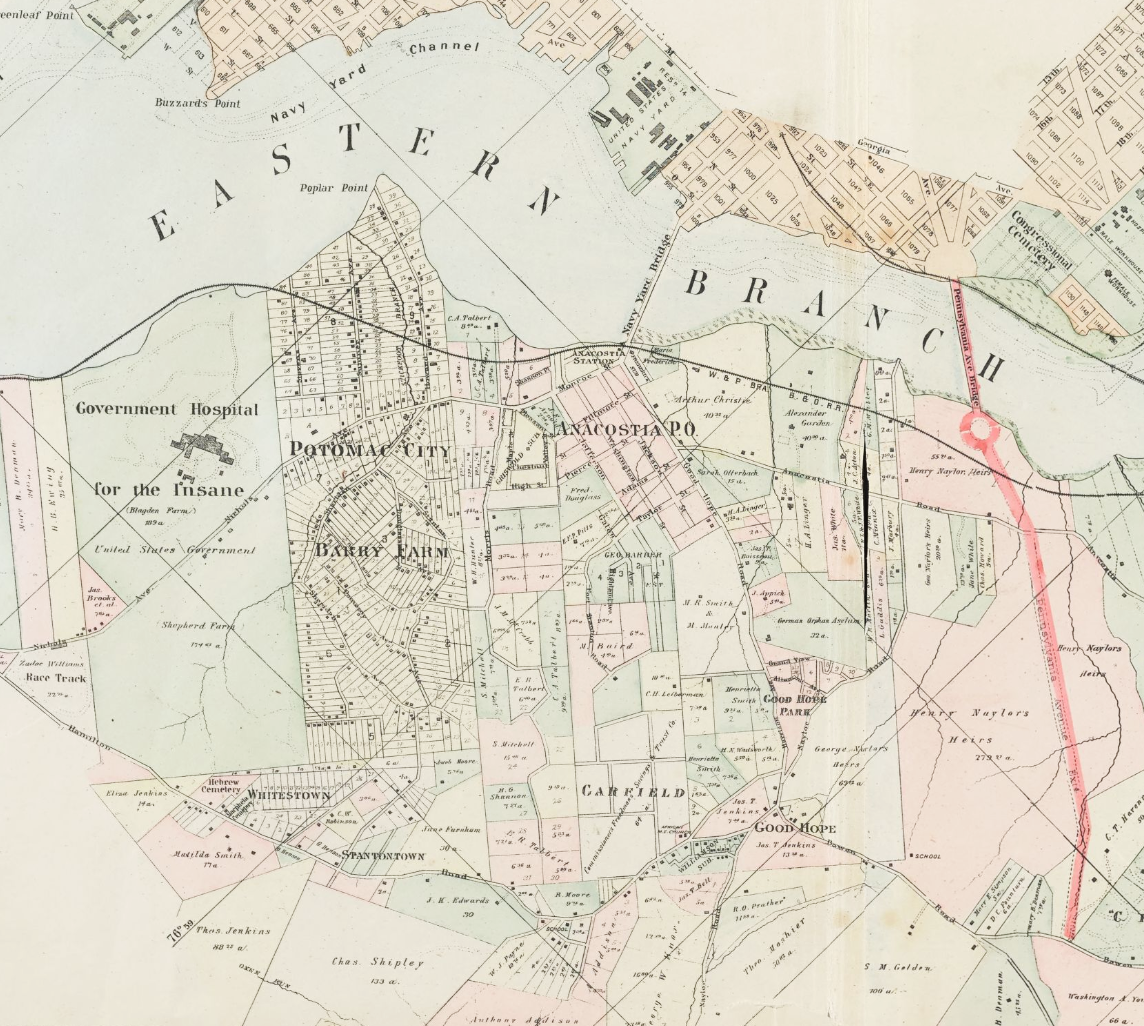

Detail of a 1887 map of D.C. Courtesy of the D.C. Public Library, Special Collections, Washingtoniana Map Collection (Source)

Detail of a 1887 map of D.C. Courtesy of the D.C. Public Library, Special Collections, Washingtoniana Map Collection (Source)

Barry Farm’s political leadership included Charles R. Douglass (Frederick Douglass’s second son), who worked to open teaching jobs to African Americans; Washington’s county schools had employed whites only. Douglass also successfully advocated to equalize white and black teachers’ wages; black women were routinely paid around a third less than their white colleagues. In 1871, after taking over his father’s seat in the D.C. House of Delegates, Douglass’s brother Lewis was the driving force behind a non-discrimination law that became the basis for desegregating the city’s restaurants, hotels, and theaters some 80 years later. Another resident, Solomon Brown, was elected to the House of Delegates by both white and black voters to represent all of Anacostia and its voting district. Brown was also the Smithsonian Institution’s sole black professional employee for many years and a frequent lecturer on science, philosophy, and politics. (As a delegate, Brown was responsible for legislation changing Barry Farm’s name to Hillsdale in 1871.) [8] The Douglasses, Brown, and other black officials helped shape public policy until the federal government effectively stripped black Washingtonians of their role in governing the city by abolishing home rule in 1874.

Other residents included attorney and justice of the peace John Moss, assistant superintendent for D.C.’s African American schools Garnet Wilkinson, and scholar Georgiana Simpson, who became one of the first black women to receive a doctoral degree upon her matriculation at the University of Chicago in 1921.[9] The well-known abolitionist Emily Edmonson, among those who had attempted to escape slavery in 1848 by sailing down the Potomac River, moved to Barry Farm in 1869, after she and her husband sold their Montgomery County farm. The Edmondsons raised their children at Barry Farm and remained there for the rest of their lives.[10] In addition to building their community from the ground up, many residents also worked at St. Elizabeths Hospital or across the river at the Navy Yard.

In 1941, the government initiated the condemnation of a 34-acre section of Barry Farm, where 23 families lived, for the construction of Barry Farm Dwellings. Although landowners resisted— their community was being uprooted and there was little property elsewhere that they could afford or would be sold to them—their land was taken through eminent domain.[11]

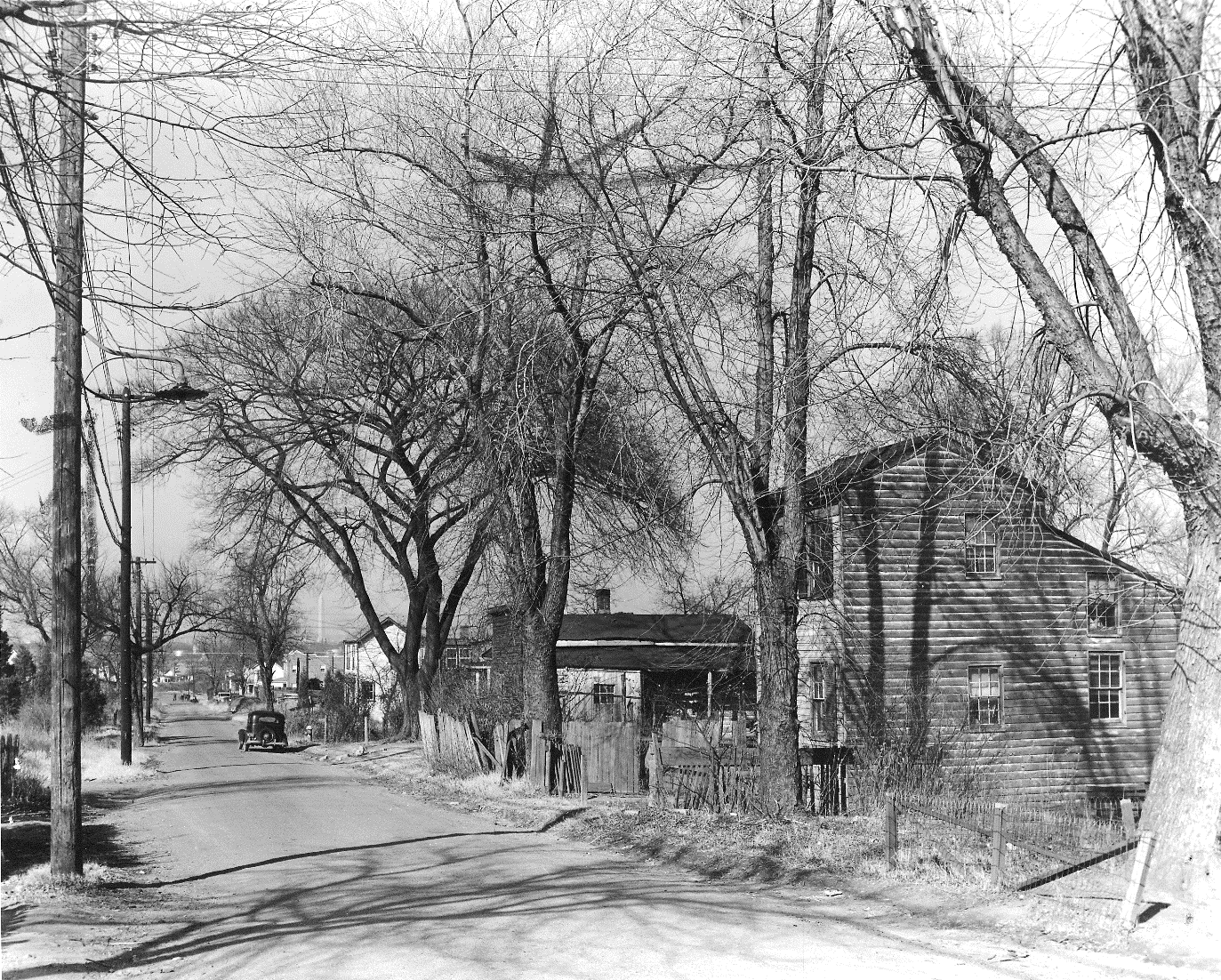

Sumner Road SE, the later site of Barry Farm Dwellings, in December 29, 1941. Photo courtesy of the D.C. Housing Authority.

Sumner Road SE, the later site of Barry Farm Dwellings, in December 29, 1941. Photo courtesy of the D.C. Housing Authority.

Public Housing: The creation of Barry Farm Dwellings

Public housing in the U.S. originated with a series of federal government initiatives begun in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, and was initially reserved for the “deserving poor”—people with steady, moderate incomes. The program expanded significantly in the early 1940s, as between eight and ten million people migrated to areas of the country offering World War II-related employment. However, most public housing was built for white residents only, and until the 1950s, all public housing was racially segregated.[12]

As D.C.’s black population increased by more than 30 percent during a period when African Americans were increasingly barred from living in much of the city or its surrounding suburbs, black residents faced a severe housing shortage during World War II. Thousands had also been displaced during previous decades, especially in the 1930s, as the city’s Alley Dwelling Authority razed much of D.C.’s black-occupied housing in neighborhoods west of the Anacostia, around Capitol Hill, and downtown.

The 1940s director of D.C.’s National Capital Park and Planning Commission, Ulysses S. Grant III, explicitly called for African Americans to be resettled in remote areas.[13] Anacostia was a semi-rural area with large tracts of open land and scattered black settlements that were easily acquired via eminent domain. However, the National Capital Housing Authority (NCHA) faced significant resistance by the real estate and building industries to the construction of public housing, and especially to housing for African Americans, whose presence was said to devalue land that could potentially be subdivided for later sale to white residents. White homeowners and citizens associations also rallied against efforts to house African Americans in proximity to neighborhoods intended for exclusive white occupancy.[14] This led the NCHA to settle on sites like Barry Farm, where black people had already lived for nearly a century.

Because many potential tenants “dread[ed] moving far away from familiar neighborhoods to the outlying sections of the city,” reported the NCHA, initially there were not enough applicants when Frederick Douglass Dwellings, Anacostia’s first public housing complex, opened in the summer of 1941. However, it was at full occupancy by February 1942.[15] Barry Farm Dwellings opened nine months later.

Children at Barry Farms Housing Development in April 1944. Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc., photographer. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. (Source)

Children at Barry Farms Housing Development in April 1944. Gottscho-Schleisner, Inc., photographer. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. (Source)

- Rear view of development (1944) (Library of Congress)

- Terrace section (1944) (Library of Congress)

- Group among trees I (1944) (Library of Congress)

- Group among trees II (1944) (Library of Congress)

The NCHA called itself a “pioneer” housing agency for establishing a graded rent system that enabled even very low-income families to have access to decent housing. “Because of its social objective,” the agency also reported that it “made the unusual provision for families with children by providing dwellings containing three or four bedrooms and by providing generous open space about the dwellings.”[17] Units at Barry Farm Dwellings contained between two and six bedrooms and the complex provided ample outdoor play areas with connecting walkways.

Barry Farm Dwellings’ design is typical of low-rent housing built during World War II, and retains the same parallel street layout it has had since 1867, when the site was first surveyed. Its lack of cross streets saved on paving and utility costs and maintained safety and privacy for residents by reducing through traffic. With just three parallel roads through the complex and houses arranges in so so-called superblocks with abutting yards, open areas were easily accessible and shared. In a report describing the project’s development, the NCHA referred to Barry Farm’s “unrationed” light and air and to the retention of old trees on the site.[16]

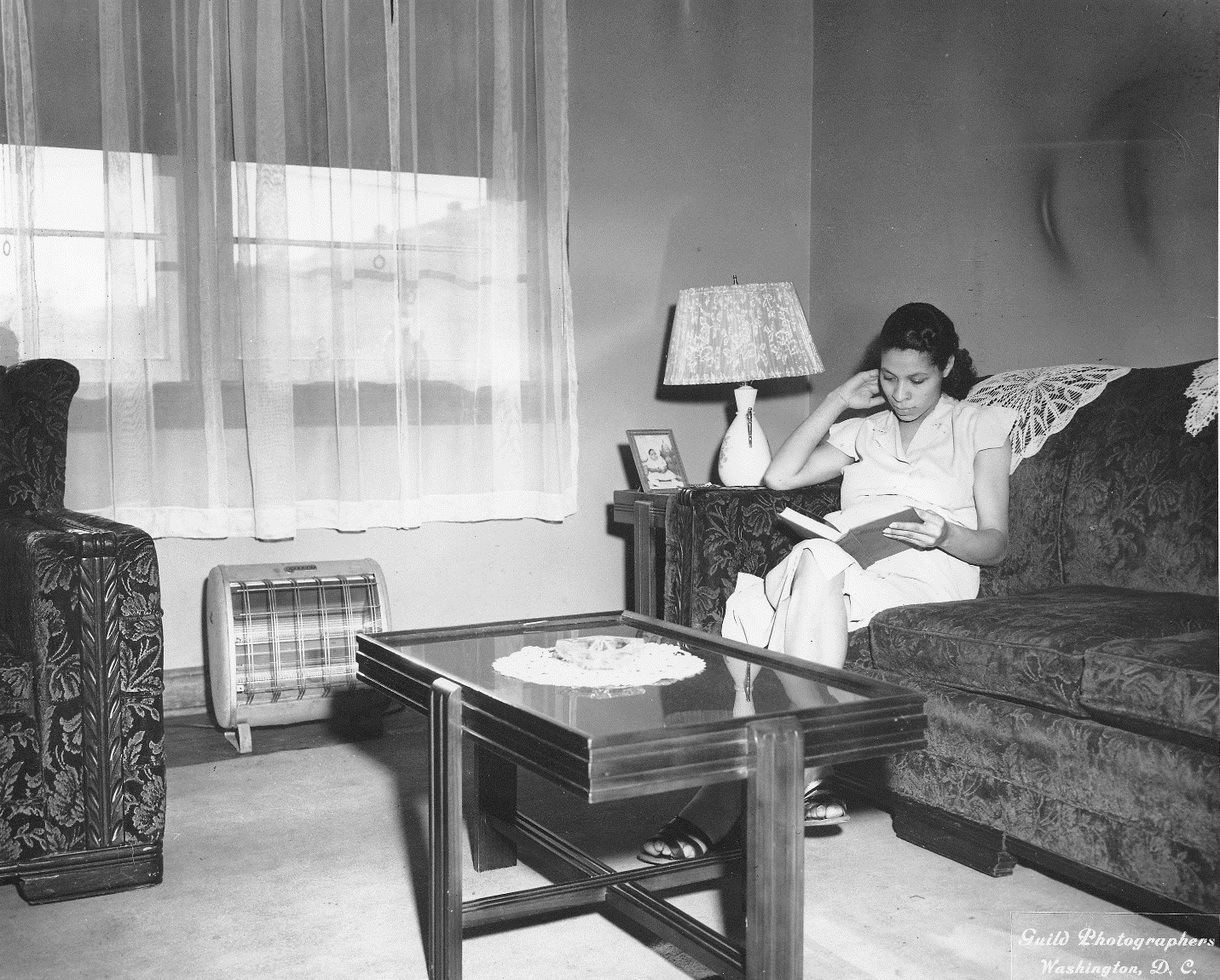

Barry Farm Dwellings interior, dated around 1950. Photo courtesy of the D.C. Housing Authority.

Barry Farm Dwellings interior, dated around 1950. Photo courtesy of the D.C. Housing Authority.

With initial priority given to people displaced by war-related projects, families began moving to Barry Farm Dwellings in November 1942. Thirteen families who had been living in a government trailer park after being forced to vacate their homes for the Navy Yard’s expansion were among the first to move in. In September 1943, Barry Farm was one of three public housing sites to which a total of 112 families were moved after being displaced for the construction of Suitland Parkway.[18] Secondary preference, as required by federal authorities, was given to people in war-related jobs or employed by the military.

Barry Farms in the early 1940s. Photo courtesy of the National Capital Housing Authority (now the D.C. Housing Authority).

Barry Farms in the early 1940s. Photo courtesy of the National Capital Housing Authority (now the D.C. Housing Authority).

Bolling v. Sharpe and the desegregation of D.C. public schools

Among those who lived at Barry Farm Dwellings by 1950 were several families whose children became plaintiffs in a lawsuit against the D.C. public schools, which required black children to attend racially segregated schools that were frequently housed in aging, overcrowded facilities. (Old school buildings originally built for white children were often designated for African American use once they began to deteriorate or become outdated.)

Navy Yard employee James C. Jennings and his wife Luberta moved with their children to Barry Farm Dwellings’ Stevens Road in 1943, just at the time that their youngest two children, Adrienne and Barbara, were old enough to start James G. Birney Elementary School nearby.[19] Seven years later, in 1950, the girls were ready for junior high, but there was not a single junior high or high school for African Americans east of the Anacostia River. Their older siblings had traveled all the way to schools in Southwest and Northwest D.C., missing out on extracurriculars due to long commutes and walking great distances when buses packed with white students from Congress Heights neglected to stop at Barry Farm. So when it was announced that a brand new whites-only school, John Philip Sousa Junior High, would open nearby on Ely Place in September 1950, the Jennings joined other neighborhood residents in organizing to fight for access.[20] Community leaders met throughout that summer, and nearly 400 signed a petition to the school board demanding that Sousa be integrated; the majority of signers were from Barry Farm.[21]

When Sousa Junior High opened on September 11, 1950, the Jennings girls joined several of their neighbors as well as the brothers Spottswood and Wanamaker Bolling, who lived nearby on Stanton Terrace, in demanding admittance to the school.[22] They were escorted by Gardner Bishop, who had cofounded the Consolidated Parents Group three years earlier to demand black access to another white junior high in Northeast, and by Reverend Samuel Everette Guiles of Campbell AME Church. After the students were turned away, attorneys filed Bolling v. Sharpe.[23] (Valerie Cogdell, of Stevens Road, was the lead plaintiff in a companion case filed the same day on behalf of several additional Barry Farm residents, but this case was abandoned in favor of Bolling.)[24]

Rather than make a case for equalizing segregated schools, as lead civil rights attorney Charles Hamilton Houston had been doing since the 1930s based on the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection, Bolling attorneys James Nabrit and George E.C. Hayes attacked segregation head-on as a violation of the 5th Amendment’s due process clause. Barry Farm residents had pushed for this approach, and threw their support behind the case by hosting fundraising dinners and raffles at Campbell AME, and by soliciting contributions to pay for legal expenses (other than the attorneys themselves, who worked for free).

“High Court Voids School Segregation, Upsets ‘Separate But Equal’ Doctrine.” Plaintiffs Barbara (left) and Adrienne Jennings, with their mother, read about the landmark Bolling v. Sharpe and Brown v. Board of Education decisions, which ended public school segregation in D.C. and nationwide. Reprinted with permission of the D.C. Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post.

“High Court Voids School Segregation, Upsets ‘Separate But Equal’ Doctrine.” Plaintiffs Barbara (left) and Adrienne Jennings, with their mother, read about the landmark Bolling v. Sharpe and Brown v. Board of Education decisions, which ended public school segregation in D.C. and nationwide. Reprinted with permission of the D.C. Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post.

Bolling v. Sharpe was dismissed by the District Courts, but in the fall of 1952, just after a new school year had kicked off with 26 overcrowded black elementary schools operating on double shifts, the Supreme Court asked to hear the case as a companion to Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. Because the District of Columbia is not a state, and not necessarily subject to the 14th Amendment’s requirement that states treat their citizens equally, it was crucial that a D.C. case be considered by the court. When the Supreme court finally ruled, in May 1954, that the racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional, Bolling v. Sharpe not only established that segregated schools violated the 5th Amendment, but that the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause applied to the federal government.[25] The Barry Farm community was central to achieving this civil rights victory.

Barry Farm’s Band of Angels and the National Welfare Rights Movement

Beginning in the late 1950s, the wholesale demolition of low-income, mostly black neighborhoods—via federally-funded “slum clearance” and urban renewal programs—changed the face of public housing. In D.C., some 80 percent of the area east of the Anacostia River was upzoned in conjunction with the mass displacement of Southwest D.C. residents for the nation’s first federal urban renewal project.[26]

By the early 1960s, public housing had become the last refuge for low-income African Americans displaced by urban renewal and redevelopment. In D.C., 94 percent of 5,000 families waitlisted for public housing in 1962 were black. The area around Barry Farm rapidly transformed into a low-to-moderate income, almost entirely black-occupied section of the city. The concentration of low-income apartment housing in an area that remained isolated from the rest of the city and from basic amenities such as grocery stores, combined with municipal disinvestment east of the Anacostia River and the legal desegregation of suburban housing, exacerbated the abandonment of this area by people who could afford to move elsewhere. [27]

Barry Farm Dwellings had begun showing signs of serious neglect by the National Capital Housing Authority by the mid-1960s, even though it was just over twenty years old. Rats and cockroaches were rampant, faucets leaked, and at least one resident’s ceiling had crashed onto her stove. The city had stopped providing even basic maintenance, such as the replacement of burnt-out street lights, not only within Barry Farm Dwellings, but throughout this entire section of the city.[28]

Many of Barry Farm’s tenants could also barely afford to feed or clothe their families, but would lose welfare benefits if they became employed. For those who had children to care for, it wasn’t worth the risk of taking part-time, low-wage, or unstable jobs that might pay even less than the minimal income provided by the government, especially when they could not afford day care and valued their role as parents.[29] But in exchange for receiving government assistance to work as unpaid homemakers, parents, babysitters for their neighbors, and in some cases, community organizers, women were frequently forced to open their doors to welfare investigators, who arrived unannounced at all hours. Entering homes without permission, investigators searched for evidence of paid employment and for the presence of male partners; having a man in the house could disqualify women from receiving public funds.[30] It was clear to residents that the city directed more resources toward surveillance than it did to basics such as maintaining furnaces and plumbing, patching in holes roofs and floors, or planting grass.[31]

In 1965, thanks to President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty—and Johnson’s call for “maximum feasible participation” by the poor in making this ambitious program a success—an infusion of federal dollars suddenly provided resources for tenant activism in Anacostia and Congress Heights. Funds were directed to Anacostia’s Southeast Neighborhood House for organizing low-income tenants of public and private housing; outreach to Barry Farm Dwellings began in February 1966.[32] With the help of trained organizers, a revived tenants council soon emerged, calling itself the Band of Angels. Led by Stevens Road residents Lillian Wright and Etta Mae Horn, who would soon help found the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO) and grow it to 25,000 members, the Angels’ first victory was a $1.5 million renovation.[33] Interior repairs deemed by residents to be most urgently needed were prioritized over exterior work proposed by planners, though outside walls were also “sandblasted and painted with waterproof paint, according to an article published later that year.[34] The Band of Angels also began picketing D.C.’s welfare department and the Alexandria home of its director. (Shirley Jones, of Stevens Road, reported that in retaliation for protesting the city’s welfare policies, the department demanded $99 from her for a six-year-old infraction.)[35]

NWRO activists marching in the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968. Barry Farm’s Etta Horn is in the front row, third from left. Photographer: Jack Rottier. Photo courtesy Jack Rottier photograph collection, Collection #C0003, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

NWRO activists marching in the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968. Barry Farm’s Etta Horn is in the front row, third from left. Photographer: Jack Rottier. Photo courtesy Jack Rottier photograph collection, Collection #C0003, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

Barry Farm’s Band of Angels formed the nucleus of the Citywide Welfare Alliance, which consisted of a least 12 groups from across the city representing some 1,300 members by 1970. The group met at Horn’s home and at the Barry Farm Recreation Center.[36] As a representative of her neighbors and of welfare recipients across the city and the nation, Horn frequently testified before Congress in support of funding welfare, food stamps and childcare. She denounced punitive policies requiring employment or job training as a criteria for public assistance, and especially decried the efforts of Congress to regulate women’s personal lives via home inspections and threats to remove children from their families.[37] “You control our lives,” she told a session of Congress in 1969. “[Y]ou sit up here on the Hill and talk about building subways and bridges and parking lots for the tourists and people from suburbia…It’s time to talk about the people who live here. It’s time to treat us like human beings.”[38]

The previous year, Horn helped lead a national Mother’s Day march that culminated in some 6,000 welfare rights supporters—among them Coretta Scott King, Ethel Kennedy, and Julie Belafonte—rallying at Cardozo High School.[39] Under Horn’s leadership, the Citywide Welfare Alliance was also victorious in securing the appointment of a committee to review procedures for determining women’s eligibility for abortions at D.C. General Hospital, and the establishment of a task force on health care for low-income D.C. residents.[40] In 1969, Horn’s final year as vice-chair, the National Welfare Rights Organization coordinated a national campaign to force department stores to extend credit to welfare recipients. Members arrived at stores en masse to demand accounts and—when rejected—waged sit-ins. Numerous department stores changed their policies as a result.[41]

Horn and the NWRO were ultimately credited with shifting the civil rights movement toward economic concerns, rather than demands for equal access. On March 31, 1968, following his first face-to-face meeting with Horn and her colleagues in early February, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his final D.C. address at the National Cathedral. There he vowed that his Poor People’s Campaign would “establish that the real issue is not violence or nonviolence but poverty and neglect.”[42]

Rebels With a Cause: Youth Organizing at Barry Farm

In addition to supporting the Band of Angels, War on Poverty funds directed to Southeast Neighborhood House also were directed to organizing low-income youth in and around Barry Farm Dwellings. The United Planning Organization (UPO)—which controlled local funds distributed by President Johnson’s Office of Economic Opportunity—began funding youth organizers in January 1965, but six months later, funds were withdrawn. After 21-year-old William Scott, of Stevens Road, helped organize a sit-in at the UPO in February 1966, the office agreed to a pilot project. Paid youth workers fanned out across Barry Farm Dwellings and the surrounding area, surveying residents, raising awareness of shared problems, and fostering engagement in a community-led movement to demand that the city address their needs. Rebels With a Cause, comprising up to 300 teenagers and young adults, formed at the same time to respond to specific issues faced by youth, who constituted around 70 percent of Barry Farm residents.[43]

Among the most dangerous issues faced by black youth, not only at Barry Farm but across the city, was discriminatory policing. The Metropolitan District Police were notoriously abusive and were rarely held accountable for brutal behavior resulting in physical harm or death. In July 1966, fifteen of the Rebels, along with seven other Barry Farm-area residents, convened a meeting with police where they asked for an opportunity meet the officers who patrolled their neighborhood. They were not only rebuffed, but five weeks later, police interrupted a community meeting to make an arrest. When residents protested in front of precinct headquarters, police attacked them with batons and dogs.[44] At the same time, despite being overpoliced by welfare investigators, Etta Horn noted the lack of police protection for Barry Farm residents. “As long as Congress Heights was white you saw police,” she remarked at a January 1967 meeting. “Now that the community has been integrated, she went on, “you don’t get the police. You get off the bus about 9:30 at night and you pray that you can get home.”[45] The Rebels would continue to demand better policing and supported youth across the city in doing the same.[46]

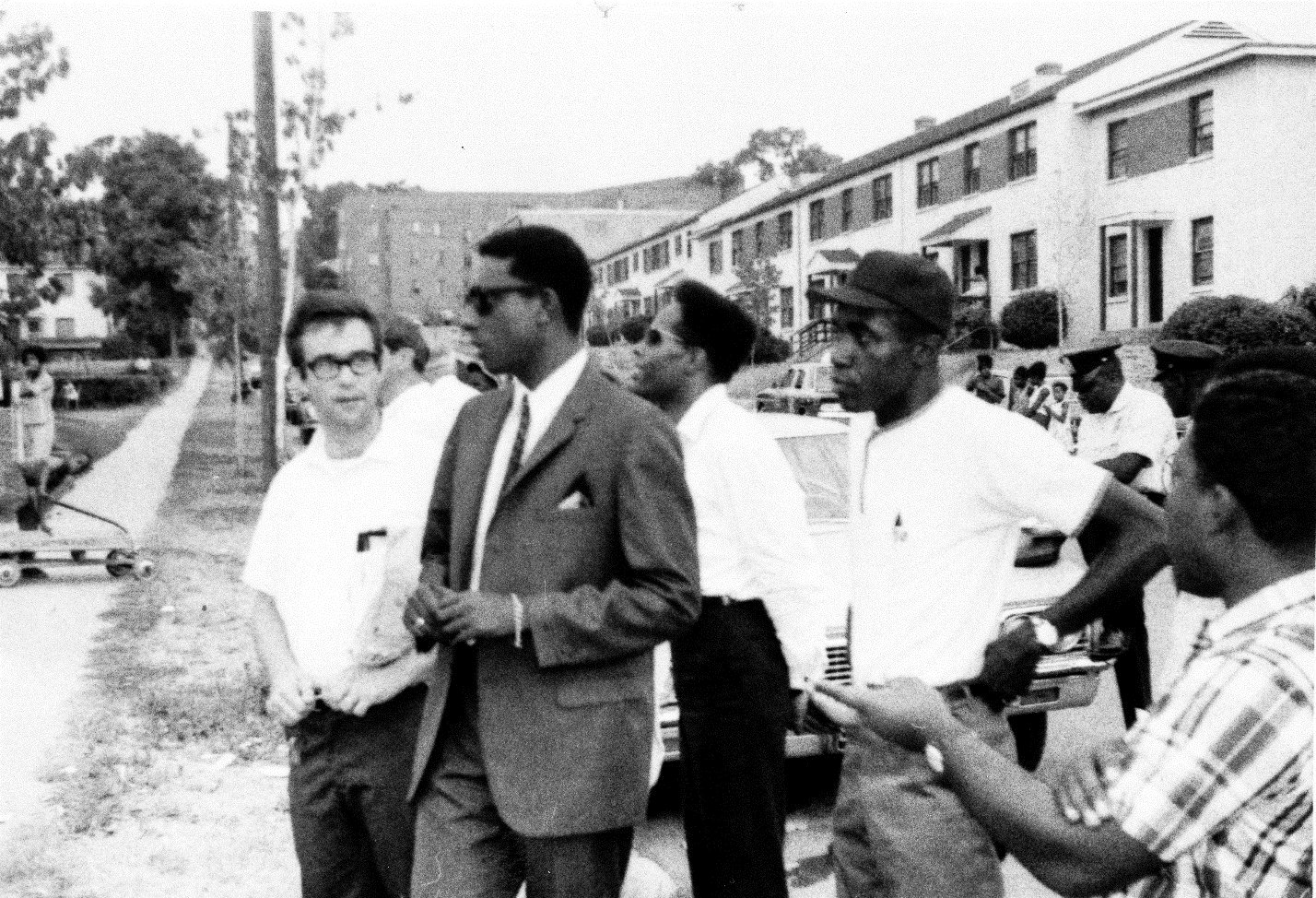

Stokely Carmichael at Barry Farm Dwellings, 1966. In July of 1966, Stokely Carmichael visited Barry Farm Dwellings and talked at a rally attended by 150 people. In this photo, he is seen on Eaton Road at the heart of the community. Philip Perkins, a neighborhood worker for Southeast Neighborhood House is standing to his left. Photo courtesy of Anacostia Community Museum Collections, Smithsonian Institution.

Stokely Carmichael at Barry Farm Dwellings, 1966. In July of 1966, Stokely Carmichael visited Barry Farm Dwellings and talked at a rally attended by 150 people. In this photo, he is seen on Eaton Road at the heart of the community. Philip Perkins, a neighborhood worker for Southeast Neighborhood House is standing to his left. Photo courtesy of Anacostia Community Museum Collections, Smithsonian Institution.

A more attainable goal was the improvement of infrastructure around Barry Farm. After 20 Rebels sat in at a District Commissioner’s office following the death of a 12-year old hit by a car, the city finally pledged to install a street light that residents had been demanding for years.[47] Funds for promised improvements to the buildings and grounds were increased and re-allocated to essential needs, such as repairing broken lights and exterminating apartments. A new playground was built at nearby Sheridan Terrace and funds allocated for a new recreation center at Douglass Dwellings. Three new swimming pools were also planned.[48]

In addition to their work at Barry Farm, the Rebels established a range of programs, from day care to cultural activities to employment services, and were ultimately recognized as a model for youth programming across the city. They became nationally known when performer Eartha Kitt toured Barry Farm during a visit to D.C., and she joined the Rebels in testifying before a House of Representatives Education subcommittee, in May 1967. Kitt pointed to the success of the Rebels—noting that 90 percent of them had police records and all were “products of a ghetto”—in urging Congressional support for the increased participation of youth in designing programs to prevent delinquency.[49]

Go-go and the Junkyard Band

In the early 1980s, Barry Farm Dwellings became a hub for D.C.’s emerging go-go scene when a group of 9- to 15-year-old residents formed The Junkyard Band. The group’s name came from its instruments, which consisted of “soda bottles, tin cans, picnic benches and whatever else they could find,” said Barry Farm Recreation Center director Freddie Bethel in an interview for the Washington Post in 1981. Under the leadership of a former Barry Farm resident who quickly signed on to manage the group, the boys performed at recreation centers all over the city, for half-time shows, and at the Washington Coliseum and the National Geographic Society, among other venues.[50] Their song “Sardines“ became a popular hit in D.C., symbolizing the city’s homegrown music culture. Nearby at 13th and V streets SE, the Panorama Room of Our Lady of Perpetual Help was also central to the emergence of go-go, hosting frequent shows by the “Godfather of Go-Go” Chuck Brown and others.

* * *

While Barry Farm Dwellings has suffered from the impacts of segregation, municipal neglect, invasive welfare policies, and racialized policing, it also has a profoundly rich history. Today’s streetscape is the only physical remnant of the site’s origin as a settlement established to ensure black advancement in the wake of the Civil War. However, Barry Farm remained a hub for political leadership and community action, a legacy that carries forward to this day.

Note

This article is based on the author’s research for the Barry Farm Dwelling’s landmark nomination, filed by the Barry Farm Tenants and Allies Association. A hearing on the landmark nomination will be held by the Historic Preservation Review Board on July 25, 2019.

Acknowledgements

The author is indebted to the work of Anacostia Community Museum curator Alcione M. Amos, for her forthcoming book History of Place: Barry Farm/Hillsdale, a Postbellum African American Community in Washington DC, 1867–1970. Amos is giving two upcoming talks on the history of Barry Farm as part of a series of public programs presented in conjunction with the Anacostia Community Museum’s A Right to the City. A related exhibit is currently on display at the Anacostia Library. The author also thanks Anacostia Community Museum Curator Samir Meghelli and Natalie Campbell/D.C. Public Library for providing access to research files and photos, and Patricia Savage for her research assistance.

Sarah Jane Shoenfeld is a principal of Prologue DC, LLC, and a co-director of the public history project Mapping Segregation in Washington DC.

Notes and references

[1] Black men gained the vote in D.C. in 1867, three years before the 15th amendment fully extended the franchise to nonwhite U.S. citizens in 1870; John Muller, Frederick Douglass in Washington, D.C.: The Lion of Anacostia (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012).

[2] Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle over Equality in Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2010), 172.

[3] Anacostia produced several local newspapers in addition to the Douglass family’s New National Era. Louise Daniel Hutchinson, The Anacostia Story: 1608-1930 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1977), 98-136.

[4] Dianne Dale, “Barry Farm/Hillsdale: A Freedmen’s Village,” in Kathryn Schneider Smith, ed., Washington at Home: An Illlustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation’s Capital, Second Edition (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U. Press, 2010); Dale, The Village That Shaped Us; A Look at Washington DC’s Anacostia Community (Lanham, MD: Dale Publishing, 2011).

[5] Hutchinson, 81-82.

[6] Hutchinson, 83-85. “The hills and valleys were dotted with lights…. The sound of hoe, pick, rake, shovel, saw and hammer rang through the late hours of the night (83).”

[7] Hutchinson, 88-89.

[8] Hutchinson, 93-97.

[9] Hutchinson, 125; Tikia K. Hamilton, “The Cost of Integration: The Contentious Career of Garnet C. Wilkinson,” Washington History 30 (1), Spring 2018, 52; Alcione Amos and Patricia Brown Savage, “Frances Eliza Hall: Postbellum Teacher in Washington, D.C.,” Washington History 29 (1), Spring 2017, 49.

[10] At a Hillsdale Civic Association meeting in 1921, the Edmonsons were listed among those who had “built” the community. Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 347-48.

[11] “Report of the National Capital Housing Authority for the Ten-Year Period 1934-1944,” 56-57.

[12] Public Housing in the United States, 1933-1949, National Register, 2004; Public Housing in Memphis, Tennessee, 1936-1943, National Register, 1996.

[13] Constance McLaughlin Green, The Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation’s Capital (Princeton U. Press, 1967), 279. William D. Nixon, “Ghettoized Housing,” Washington Post, Jan. 8, 1949. The National Capital Parks and Planning Commission’s early members also included segregationist city planners Harold Bartholomew and J.C. Nichols.

[14] William R. Barnes, “A Battle for Washington: Ideology, Racism, and Self-Interest in the Controversy over Public Housing, 1943-1946,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society 50, 1980, 452-483.

[15] Report of the National Capital Housing Authority for the Ten-Year Period 1934-1944, 43-46.

[16] Report of the National Capital Housing Authority for the Ten-Year Period 1934-1944, 203. Specific principals of site organization and design guided the development of public housing during this period. Well-designed housing projects were meant to promote physical and mental health by maximizing natural light, ventilation, privacy, and communal space for social contact and recreation, with buildings occupying a relatively small percentage of the whole site.

[17] Report of the National Capital Housing Authority for the Ten-Year Period 1934-1944, vii, x.

[18] Report of the National Capital Housing Authority for the Ten-Year Period 1934-1944, 116; “New Housing Is Assured 112 Evicted Families,” Evening Star, Sep. 9, 1943.

[19] Adrienne and Barbara Jennings were 2 and 3 years old in 1940 (U.S. Census).

[20] Sousa Junior HS is designated a National Historic Landmark based on its role in Bolling v. Sharpe.

[21] Minutes of the Board of Education Meeting, Sep. 6, 1950: 170-73, Sumner School Museum and Archives.

[22] The Bollings lived at 1732 Stanton Terrace (WWII draft registration for Spottswood T. Bolling [Sr.], 1942; Boyd’s Directory, 1943 and 1954.

[23] The October 1953 Supreme Court complaint, Spottswood Thomas Bolling, et al., Petitioners vs. C. Melvin Sharpe, et al., lists Spottswood and Wanamaker Bollings first, followed by Sarah Louise Briscoe, of 1232 Eaton Road SE, and Adrienne and Barbara Jennings.

[24] The plaintiffs in this case were Valerie Cogdell, of 1259 Stevens Road, Wallace Morris, of 1234 Eaton Road, Felicia Brown, of 2609 Pomeroy Road, and Lauretta Parker, of 1149 Stevens Road (Valerie Cogdell, et al. v. C. Melvin Sharpe, et al, CV-4950, 1950); Rachel Devlin, A Girl Stands at the Door: The Generation of Young Women Who Desegregated America’s Schools (Basic Books, 2018).

[25] “Segregation in public education is not reasonably related to any proper governmental objective, and thus it imposes on Negro children of the District of Columbia a burden that constitutes an arbitrary deprivation of their liberty in violation of the Due Process Clause. In view of our decision that the Constitution prohibits the states from maintaining racially segregated public schools, it would be unthinkable that the same Constitution would impose a lesser duty on the Federal Government.” (Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 1954); Richard A. Primus, “Bolling Alone,” Colum. L. Rev. 104, no. 4 (2004): 975-1041.

[26] Office of the Assistant to the Mayor for Housing Programs, “Washington’s Far Southeast 70,” 1970 (Anacostia Community Museum Archives)

[27] Ibid., “Washington’s Far Southeast 70,” 1970; Mary v. Burner et al. v. Walter E. Washington et al. (1971); Thomas J. Cantwell, “Anacostia: Strength in Adversity,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, 49 (1973/74), 330-370.

[28] Cantwell, ibid.

[29] The average annual income of welfare recipients was 53.7 percent below the federal poverty level, with officials acknowledging that welfare checks were calibrated to cover just 85 percent of 1967 living costs (Anne Valk, Radical Sisters: Second-Wave Feminism and Black Liberation in Washington, D.C., 2008, 40-41).

[30] “Hope Ebbs and Tempers Rise,” Washington Post, Dec. 25, 1966; “Welfare Mothers Fight for Dignity,” Washington Post, Feb. 7, 1967.

[31] “…our houses were run down, the field rats were coming in through the house and coming up under the floor and to my kitchen, traveling. I was on welfare, and you never know when you had to open up the door for the investigator, who would come and search all through the house. There was no recreation, there was no light…. You didn’t have any rights, we didn’t have any rights at all. If the investigator came out and said well, I think you were doing so and so…. That was the kind of fear, and I shouldn’t have had it. Because I’ve gotten tired of the man coming to look under the beds, behind the dresser, under the dresser, in the closet (Etta Horn interview with Mary Kotz, Nov. 20, 1974, Tape 143, Collection 1304A, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, WI).”

[32] “Etta Horn and Life,” Washington Post, Sep. 6, 1970.

[33] “Band of Angels, Rebels With a Cause, Give Housing Chief Tough Afternoon,” Washington Post, Feb. 18, 1966.

[34] Asch and Musgrove, 348. “Since we live here we are best qualified to advise [Mayor Walter] Washington on how the funds should be spent in the best interests of our community,” declared Lillian Wright (“‘Angels’ from Barry Farms War on Public Housing Unit,” Washington Post, Feb. 18, 1966); “D.C. Tenants Lose Their Fears And Learn to Mobilize for Action,” Washington Post, May 29, 1966; A May 6, 1966, letter from NCHA director Walter Washington to Mrs. Mary Taylor of the Barry Farm Tenant Council said that “sandblasting and painting” would begin in June. Plans for other exterior and interior work is also described (John Kinard Collection, J.K. Book, Box 121, Anacostia Community Museum Archives). James G. Banks, a former D.C. housing official who grew up in Barry Farm in the 1920s-30s, later wrote, “Though we pay homage to family and community as the foundations of our civilized society, public responses…seem to be restricted primarily to the provision of more money for more physical improvements. (The Unintended Consequences: Family and Community, the Victims of Isolated Poverty, 2004, 1)” A September 1970 Washington Post article described Barry Farm Dwellings as “the National Capital Housing Authority’s grimly pastel version of a Mediterranean village. (“Etta Horn and Life,” Washington Post, Sep. 6, 1970)”

[35] “Welfare Accused of Using Old Charge to Heckle Picket,” Evening Star, May 28, 1966.

[36] “Welfare Activist Moves from Street to Office,” Washington Post, May 17, 1975.

[37] As a leader of the NWRO, Horn likely helped organized a September 1966 national Poor People’s March in D.C., a precursor to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1968 Poor People’s Campaign. More than 2,000 people participated in the march, representing 31 delegations “from communities as disparate as Harlem and McComb, Mississippi,” according to NWRO historians Nick and Mary Lynn Kotz. In August 1967, Horn helped stage the group’s first national convention at D.C.’s Trinity College. The group, made up of 30 chapters and around 400 delegates from across the country, joined 2,000 others in a march down Pennsylvania Avenue to protest a punitive welfare bill. The NWRO’s campaign against the bill galvanized welfare rights groups across the country. Nick Kotz and Mary Lynn Kotz, A Passion for Equality: George A. Wiley and the Movement (New York: W.W. Norton, 1977), 203-05, 215-17.

[38] Premilla Nadasen, Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States (NY: Routledge, 2005), 47.

[39] 12 May 1968: 6,000 Join National Welfare Rights Org Mother’s Day March & Rally. On April 17, 1968, the Citywide Welfare Alliance announced a sit-in to protest a work requirement and reductions in welfare, which were among the provisions of a bill passed in 1967. (Carol Honsa, “Welfare Mothers Plan District Sit-In,” Washington Post 18 April 1968). During an overnight vigil on Capitol Hill, 39 NWRO protesters were arrested.

[40] This was the outcome of a lawsuit the group filed in 1969. The impact of the city’s overly strict requirements was evidenced by the number of women who sought treatment at D.C. General for complications from self-induced or illegal abortions (500) versus the number who received abortions at the hospital (8). Anne Valk, “Mother Power:” The movement for welfare rights in Washington, D.C., 1966-1972, Journal of Women’s History 11:4, Winter 2000.

[41] Premilla Nadasen, Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States (2005), 109-111.

[42] In February 1968, Horn was among a group of NWRO leaders who met with Dr. King in Chicago. King had endorsed the group’s demand for a universal basic income and embraced the concept of a “poor people’s campaign,” but had been unwilling to meet with the group until then. Horn was the first to interrogate King on his knowledge of the recent welfare legislation and joined her colleagues in bringing him up to speed (Kotz and Kotz, 248-49, etc.).

[43] “Barry Farm’s ‘Rebels With a Cause’ Organize to Get Help for Project,” Washington Post, Feb. 23, 1966; “D.C. Tenants Lose Their Fears and Learn to Mobilize for Action,” Washington Post, May 29, 1966.

[44] Anne Valk, “Separatism and Sisterhood: Race, Sex, and Women’s Activism in Washington, D.C., 1963-1980, Ph. D dissertation, Duke Univ., 1996, 132; “Probe Panel Named in Anacostia Unrest,” Evening Star, Aug. 17, 1966, 1.

[45] During the previous year, as tensions had increased over abusive policing practices in Congress Heights, Horn had also drawn attention to the lack of protection for black residents after Marie McRae, 35-year old mother of six, was murdered. McRae’s family lived on the 1300 block of Stevens Road, and had taken refuge in a neighbor’s apartment after McRae was threatened by a male acquaintance and her son and neighbors had called the police. “If the police had showed up last night, six children wouldn’t be motherless,” remarked Horn. “The people down here might as well prepare to meet Jesus if anything happens, because the police aren’t going to help them.” (“Protesters Lay Killing in SE to Police Neglect,” Washington Post, Aug. 28, 1966; “New Protest in Anacostia,” Sunday Star, Aug. 28, 1966, 1.)

[46] “Police and UPO Aide Cooperate, Quiet Crowd,” Evening Star, May 14, 1967.

[47] “‘Rebels’ Press District for New Traffic Light,” Evening Star, Jul. 23, 1966.

[48] “‘Rebels With a Cause’ Changing D.C. Ghetto Life,” June 22, 1967, Jet 32 (11); “Eartha Kitt Joins SE Rebels In Appealing for a Cause,” Washington Post, May 23, 1967.

[49] “Eartha Kitt Joins SE Rebels In Appealing for a Cause,” Washington Post, May 23, 1967.

[50] Edward D. Sargent, “Transforming Junk into Funk: A Movin’ and Groovin’ Anacostia Band that Salvages – and Swings,” Washington Post, Mar. 5, 1981.

Feature photo of Barry Farm Dwellings in April 1944 courtesy of the Library of Congress (Source)