On Monday February 7, 2022, Executive Director Yesim Sayin Taylor provided written testimony to the D.C. Council Committee of the Whole Public Oversight Hearing on Bill 24-301, the “Business and Entrepreneurship Support to Thrive (BEST) Amendment Act of 2021.” You can read her testimony below, or download a PDF copy.

My name is Yesim Sayin Taylor, and I am the Executive Director of the D.C. Policy Center—an independent non-partisan think tank advancing policies for a strong, competitive, and vibrant economy in the District of Columbia.

Bill 24-301 will greatly simplify the steps businesses will need to take in order to obtain the licenses necessary to operate a business in the District of Columbia. This reform is much-needed. According to the District’s Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs, there are 11 broad categories of business licenses with 65 different subcategories of business licenses, in addition to a separate category of regulated businesses.[1] But this picture does not reflect all the requirements embedded in the D.C. Official Code or the city’s municipal regulations. There are many other categories still on the books, with fewer than 20 licensees, which could be brought back into the mix at any time.[2]

There are costs to this complicated system without any discernible public benefits.

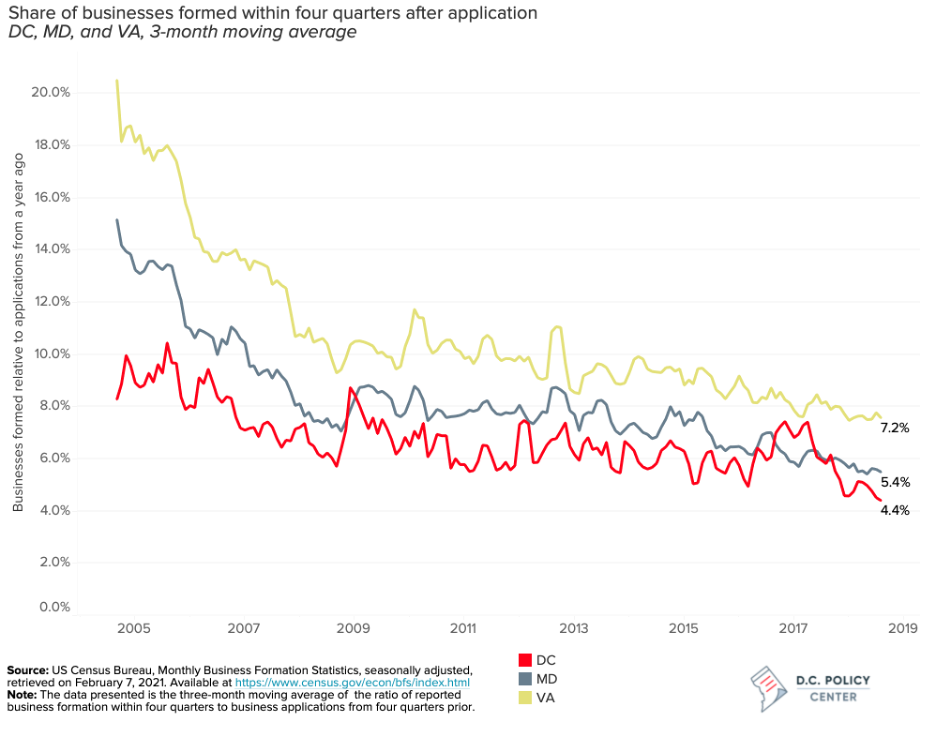

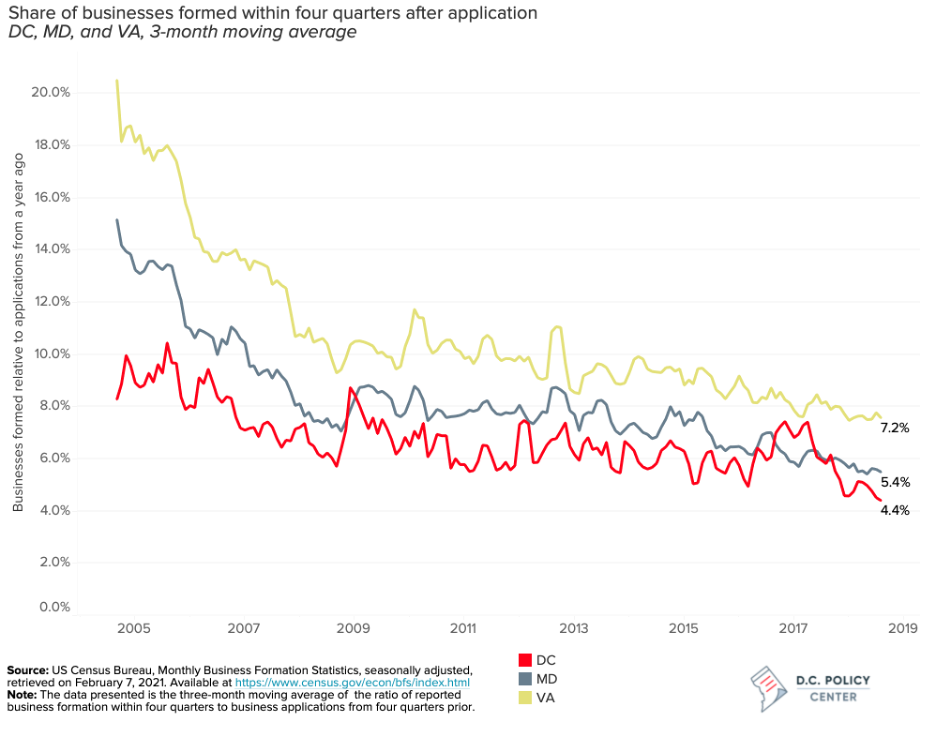

Compared to surrounding jurisdictions, a small share of business applications turn into actual businesses within a year.

Data from the U.S. Census Bureau show that while business applications in D.C. have grown through the pandemic, only about 4.4 percent of these applications turn into actual, wage-paying businesses within four quarters. This share is much higher in surrounding jurisdictions: for example, in Virginia, over 7 percent of business applicants can turn into real businesses within a year, and in Maryland, this share is over 5 percent (see Appendix Figure 1.)

Importantly, in Virginia and Maryland, even more entrepreneurs are able to turn their applications into real businesses within two years: 10 percent of all applications turn into real businesses within two years in Virginia, and 8 percent in Maryland—in both cases, higher than the one-year share. In contrast, business formation rate relative to applications in two years is lower than the one-year rate in D.C. (2.5 percent), suggesting that a significant number of new businesses close within a few quarters of opening.[3]

Businesses thrive in the absence of regulatory thicket.

While there are many reasons why business applications do not turn into actual wage-paying businesses, inability to figure out the system, and inability to pay for the costs are certainly among the important factors that impact entrepreneurs’ ability to start a business. Research shows that business formation is stronger in places where the administrative process for starting a business is simplest.[4] By simplifying the licensing process, and reducing the costs of license applications, Bill 24-301 will go a long way to remove barriers to business formation in D.C.

There are other barriers to business formation that the Council can remove.

In addition to enacting the provisions of Bill 24-301, the Council should consider other reforms that can further simplify the business application process and remove barriers.

First, the Council could consider a system where a temporary one-year basic business license is automatically issued when someone registers a business. This will allow the applicant to begin implementing their business plan without having to tangle with burdensome licensing requirements.

Second, the Council should consider increasing the limit for the Clean Hands test from $100 to a much higher level. The city requires that business license applicants must sign an affidavit (known as Clean Hands) stating that they do not own more than $100 in fines, fees, or back taxes to the city. In practice, the city does not check applications against amounts owed to the city (other than taxes). But the requirement to sign such a statement could dissuade residents who own more than $100 in traffic fines, court fees, environmental fines, or other fees. Such burdens more heavily impact low-income residents and residents of color, and the threat of clean hands is more likely to dissuade enterprises of color from applying for a business license.[5] There is already legislation under Council review that would increase the Clean Hands threshold to $5,000.[6] We encourage the Council to adopt this legislative proposal.

Third, the District should double down on its information infrastructure investments across the entire city. By far, online retail has been the fastest growing component of new businesses and new business applications. On this front, the pandemic has operated as a leveler, as it has reduced the dependence of retail on access to high-value storefronts. The success of such remote businesses depends on access to reliable and high-capacity internet access, and we have observed how the digital divide amplified racial inequities when schools switched to online learning in the spring of 2020.[7] Making high quality high-capacity internet available free or at low cost to every District resident who would otherwise not be able to pay for such access can greatly help business startups especially in less resourced parts of the city.

Fourth, the District should find other means of support to turn online businesses into brick-and-mortar businesses. With increased vacancies in the city’s key employment centers, there is an opportunity to provide cheaper office and retail space for a more diversified set of businesses. The District could offer incentives for new businesses to take space in vacant office buildings or encourage landlords to provide such space. This could be done in the form of rent subsidies, tax incentives, or even a program whereby the city chips in for a portion of the rent for startups that have a commitment to stay in the city.

The economic future of the District of Columbia depends upon the return of a strong demand for urban amenities. The increased entrepreneurial activity combined with the need to fill empty office buildings offer the District a unique opportunity to create economic vibrancy with a more diversified business base. The District can either ride this current entrepreneurial wave by doing away with its burdensome regulatory regimes, or it could watch it crash as more residents find it harder to survive in the city.

Appendix Figure