Despite the considerable number of unfilled jobs coming to the Washington region every year, young D.C. residents, particularly young people of color, do not have access to career pathways designed to support them from education to secure employment. We believe that employers have uniquely powerful levers to influence racial equity through talent development, starting with how they engage with the education and workforce systems and including their own talent acquisition and development practices. Our vision is that provided with the right infrastructure and support, employers will be able to hire more DC residents into the region’s many good jobs as a business decision advanced by their Human Resources departments—not only out of a sense of corporate social responsibility.

This publication is the first of two in partnership with the Federal City Council and CityWorks DC that will explore the creation of a local talent pipeline in the District of Columbia that prepares youth for high-wage, high-demand jobs in the region by enabling District employers to actively engage in the education and training of the District’s youth.

Read the second publication: D.C. high school alumni reflections on their early career outcomes

The District of Columbia and the greater Washington metropolitan area have always been great places to live and work. High wages, high quality of life, and a stable hiring environment with a depth of talent has attracted workers from all parts of the nation and all corners of the world. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau suggest that in any given year, about five percent of the private sector workforce in the District (including those who live in Maryland and Virginia) are newcomers who have moved to the region either from another state or another country.[i] In 2019, just before the pandemic, for example, there were an estimated 23,000 newcomers in the District’s workforce[ii], and they took one in five new jobs opened in the city that year.[iii]

In this hiring environment, unfortunately, it is easy to predict who is being left out. In 2019, of the 415,828 District residents between the ages of 17 and 64 who were not in school, 53,471 (13 percent) were not working.[iv] Three quarters of these non-working adults were Black residents without college credentials, leaving them with little hope to qualify for the majority of the 117,000 jobs filled that year. Each year, more young Black people born and raised in the District are added to this pool of residents without access to high-wage, high-potential jobs, which perpetuates a vicious cycle that results in a lifetime of low opportunities.

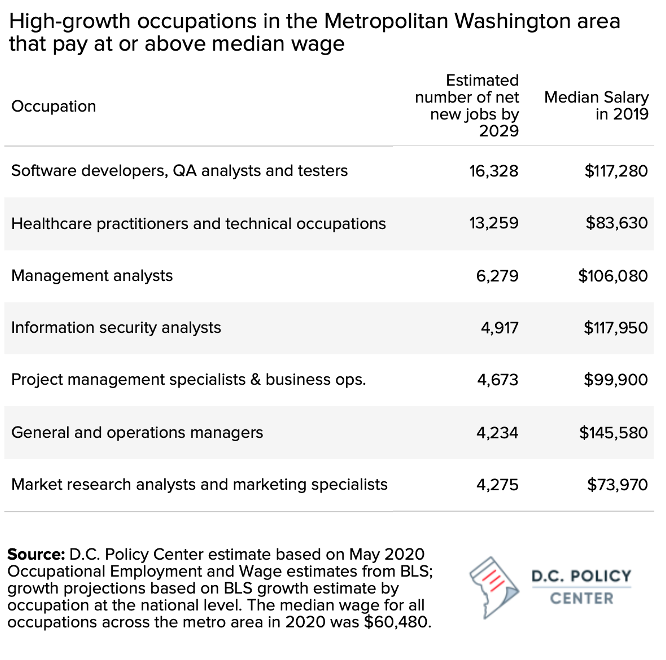

In the wake of the tragic deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and too many others to name, many corporations and large employers have pledged their commitment to build a more diverse, equitable workforce. Employment projections suggest that there is a real opportunity to meet this pledge. Both in the District of Columbia and in the greater metro area, employment is projected to bounce back to pre-pandemic levels by 2022.[v] Importantly, over the next decade, the need for talent in the high-wage areas of information technology (IT), business operations, and health care will grow.

Even under very conservative estimates—assuming the regional employment in these high-wage occupations would grow at the same rate as the rest of the country—between now and 2029, the region will likely add over 50,000 software developers, health care workers, management analysts, information security analysts, project managers, and business and marketing analysts, all of which pay at or above the median wage. But the region will likely grow much faster: one estimate puts the number of digital technology job opportunities that would open in the region over the next five years to as high as 130,000.[vi]

Thus, we have both a commitment to racial equity from employers and the need to hire new workers, but we still lack a system to bring these two together. Unless we do something differently, these high-wage, high-potential jobs will continue to elude many youth who grew up in the District.

What is the local talent pipeline?

To unlock more opportunities, the District’s youth need to be able to get hired for good jobs with high earning potential and paths for career growth.[vii] What prevents youth from finding high paying jobs is not the lack of jobs, but disparities in opportunities for preparation, education, and credentialing that opens access to employment. For instance, youth lack equitable access to experiences to learn from employers, e.g. job shadowing, mentoring, internships, etc., which limits their career prospects and economic mobility. To overcome these disparities, the District must invest in building a local talent pipeline that enables District employers to actively engage in the education and training of the city’s youth[viii], so they can become co-developers of human capital, not simply consumers of it.

We define the local talent pipeline as a new system that reliably connects the District’s youth to local employers with the goal of creating long-term employment made up of the following key stakeholders:

- Young adults who are attending or have attended District’s public schools and who want to remain in their communities.

- Employers who engage these young adults to help them gain knowledge and skills so they can be hired when a role is available.

- The District’s public PK-12 and postsecondary education that provides opportunities for training and work-based learning incorporated into youth’s learning.

- Non-profit organizations and government agencies that provide necessary coordination and wraparound supports to learners.

- A policy and regulatory framework from the District of Columbia government that is necessary to support work-based learning, credentialing, and employment.

- Philanthropic organizations and D.C. government that provide private and public funding to support learners and build required infrastructure.

The main objectives of creating a local talent pipeline are to prepare District’s youth for employment and to provide regional employers with the diverse workforce they seek. While a local talent pipeline can include training in both hard skills and soft skills, employment and apprenticeship services, and supportive services such as mentoring, childcare, food assistance, transportation and housing, a pipeline’s differentiating role is that it creates paths for District employers to actively engage in the education and training of the District’s youth.

Importantly, creation of the local talent pipeline goes beyond creating a workforce program. Good workforce programs are necessary, but not sufficient, to ensure that the District’s young people are prepared to be competitive for the high-wage, high-potential jobs that are opening in the metropolitan Washington region. The creation of the local talent pipeline requires a system change, including a shared vision across all key stakeholders, an infrastructure to bring all necessary components together, and policies and practices that are needed to execute the vision including supports that connect the District’s youth to local employers for long-term employment.

Why should we invest in building a local talent pipeline?

Although the region’s ability to attract and retain growing businesses is deeply connected to the depth of talent ready move from anywhere in the world,[ix] this leaves out current residents—especially those furthest away from opportunity—in benefiting from the prosperity created by economic activity. District residents who find themselves outside of the workforce are also among those most likely to suffer the consequences of concentrated poverty.[x] They are more likely to experience trauma, physical and mental health problems, and economic instability, or be involved with the criminal justice system.[xi] They live shorter lives.[xii] They are less engaged in civic activities, are less likely to vote or organize, and therefore their communities have a muted voice in the city’s policies.[xiii] Their children, too, will likely have fewer opportunities, creating a vicious cycle that deepens poverty and increases human suffering.[xiv],[xv]

Thus, there are good social reasons to invest in a local talent pipeline. A larger resident workforce with strong income growth potential would increase prosperity in all parts of the city, reducing the need for social assistance, contributing to neighborhood stability, increasing civic participation and volunteerism, reducing crime rates, and strengthening the revenue base. Since communities of color tend to be further away from opportunity than their White peers, investing in the future success of local youth would also help reduce racial inequities and create more economically diverse and resilient neighborhoods.

There are also good–and profitable–reasons for employers to invest in developing a local talent pipeline. Businesses need top talent to grow and be competitive. But even in a city like the District of Columbia where talent can be imported, there is economic value in investing in creating a pipeline of local youth for future hiring. First, a local workforce, with its strong ties to the community, typically has lower job turnover, creating a more stable workforce (and lower costs of internal training and orientation) for employers.[xvii] The presence of a local talent pipeline increases recruitment efficiency and workforce diversity, and creates a workforce with higher morale. When employers support their communities by creating employment opportunities for local youth, they reap high reputational returns, and benefit from a more devoted customer base.[xviii]

Does the District’s labor market create opportunities for its youth?

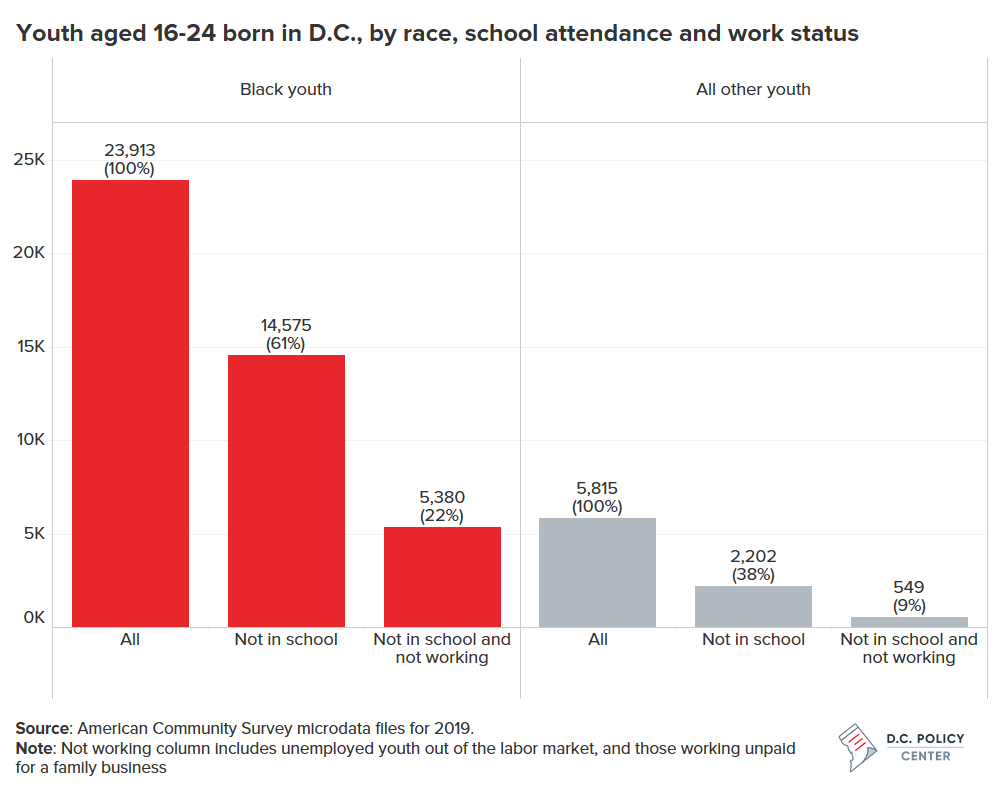

The presence of a strong university network in the District attracts a significant number of young people to the city, but the opportunities that the District’s universities provide for students from all over the country sometimes conceal the lack of opportunity for some youth born and raised in the city. Of the 82,160 youth aged 16-24 who lived in the District of Columbia in 2019, only 29,734 grew up in the city. Eighty percent of residents in this category are young Black people, and among them, only four out of ten are currently in school. Importantly, one in five of the District’s Black youth are neither in school nor working. In contrast, among youth of all other races and ethnicities, only one in ten are neither in school nor working.

The unequal life outcomes of the District’s youth begin when they are in school. For every 100 students that start high school together, 31 will not graduate high school within four years, 30 will graduate high school but will not attend post-secondary education, and 25 will enroll in a post-secondary institution but will not graduate.[xix] Black and Hispanic or Latino D.C. students, English learners, and students with disabilities are more likely to fall behind in high school[xx] and are less likely to attend or complete post-secondary education. Although the District has made significant strides in improving public education in the last decade, we need to accelerate our progress and work more closely with employers.

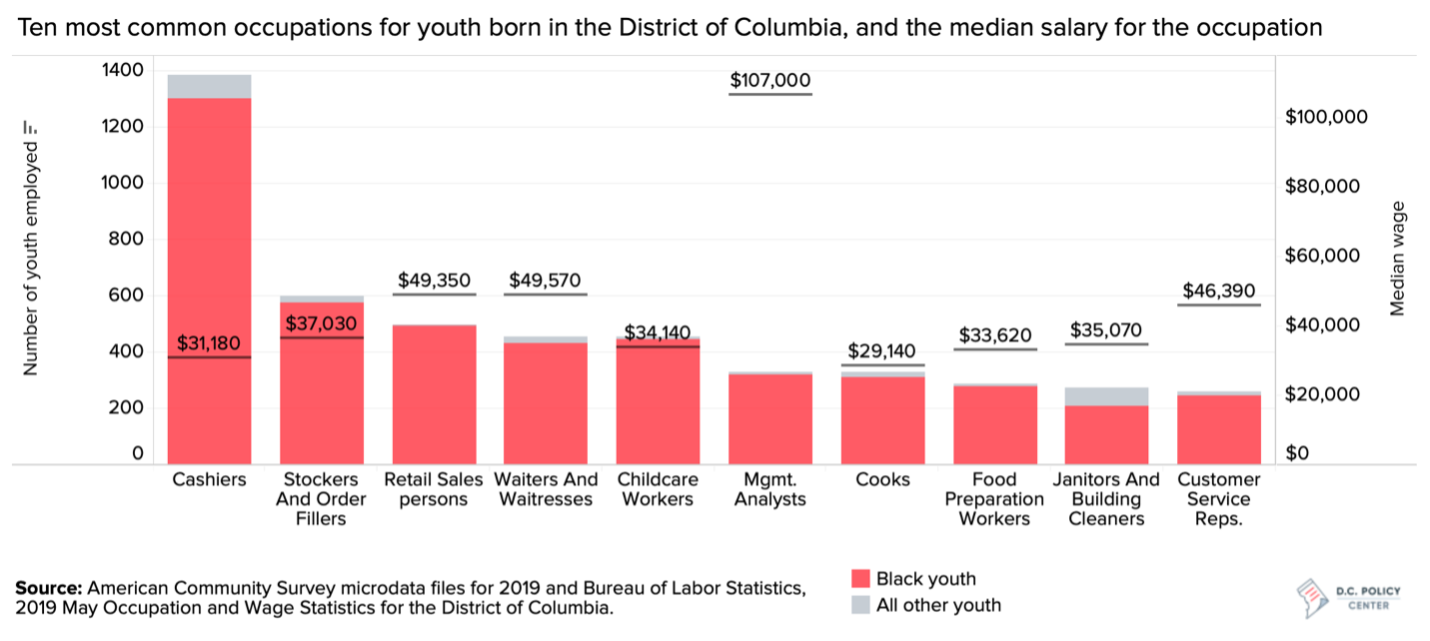

Even when District born and raised youth find jobs, they are likely to be in low-paying occupations with little opportunity for economic mobility. The most common job among youth from D.C. and who are not in school is that of cashier (with a median wage of $31,180).[xxi] Across the top 10 occupations held by youth who grew up in the District, five have median annual wages that are at or slightly above the minimum wage, and only one has a median annual wage that is higher than the median wage across all occupations (management analysts, with a median wage of $107,000 in 2019 compared to the citywide median of $89,900). And as these youth age and become core members of the District’s workforce, their opportunities do not always expand. The top 10 occupations held by D.C.-born residents between the ages of 45 and 64 include four that pay right around the minimum wage mark (cooks, cashiers, janitors, and drivers), and only one (managers) that pays above the area median salary.

What is the cost of not investing in a local talent pipeline?

The District’s youth education and employment outcomes underscore the urgency of the problem. Every young adult who is excluded from the regional labor market each year adds to a pool of residents who are further pushed into poverty or pushed out of the city. By predictably preparing youth for more lucrative careers, a local talent pipeline will increase their economic mobility and wages.

There is an economic cost to continuing on our current path. Data suggest that the Washington region faces a shortage of talent in numerous high-wage, high-demand occupations that are vital for the businesses in our region to thrive. For example, one estimate puts the number of tech and tech-related jobs that would go unfilled in the region annually without a dramatic increase in developing talent to 60,000.[xxii] Despite the strong presence of universities that cultivate talent, the metropolitan Washington area is among the regions that have experienced the greatest amount of “drain,” largely due to the relatively expensive cost of living.[xxiii] In the absence of talent that can meet the labor demand from employers, the region’s economic growth and competitiveness will likely suffer. These trends make it even more important to cultivate local talent who can meet the labor demand and help push forth the region’s economic growth.

There is a social cost to inaction as well. Workforce preparedness is an issue of racial equity in the District as Black and Hispanic residents are more likely than white residents to be without advanced degrees, more likely to work in low-wage jobs, more likely to be returning citizens, and more likely to be unemployed. A local talent pipeline also can help ensure that the District’s workforce has skills that matches those that are required by local employers, which, in turn improves regional competitiveness, and supports economic growth.[xxiv] Importantly, a local talent pipeline can help those furthest from opportunity to be a part of this growth, thereby reducing social and economic inequities that have been amplified during the District’s recent history.

What do we need to build a strong local talent pipeline?

This brief is the first of a series that will explore what youth and employers want and need to have a meaningful pre-employment engagement that leads to good jobs for those who are furthest away from opportunity, and good workers for employers. Future topics will include an exploration of what District’s employers currently do to engage local youth, how employers can align their activities through under-explored linkages across different industries, how the District can create a regulatory and legal environment that creates opportunities for employment for youth, whether there are examples of pre-employment engagement of youth by employers that could serve as a basic model for a city-wide local talent pipeline, what youth want, and areas where District’s programs need more alignment with employer and youth needs, among others.