On Tuesday, D.C. Council unanimously advanced a bill that would make all Metrobus rides that begin in the District of Columbia free (upon approval of the WMATA Board). The fare-free rides are estimated to cost $34.4 million per the fiscal impact statement issued by the OCFO. In addition, the bill provides $8.5 million to support the 24- hour daily operation of twelve Metrobus routes serving major transportation corridors and activity centers, and $10 million to further improve or expand bus service in underserved parts of the city.

When the fare-free program begins, anyone who starts a bus trip in D.C., regardless of their residency, will pay no fare. Presumably, for D.C. residents, this will be almost all the trips they make on the Metrobus. For MD and VA residents, these will be the trips they take going back home from D.C.

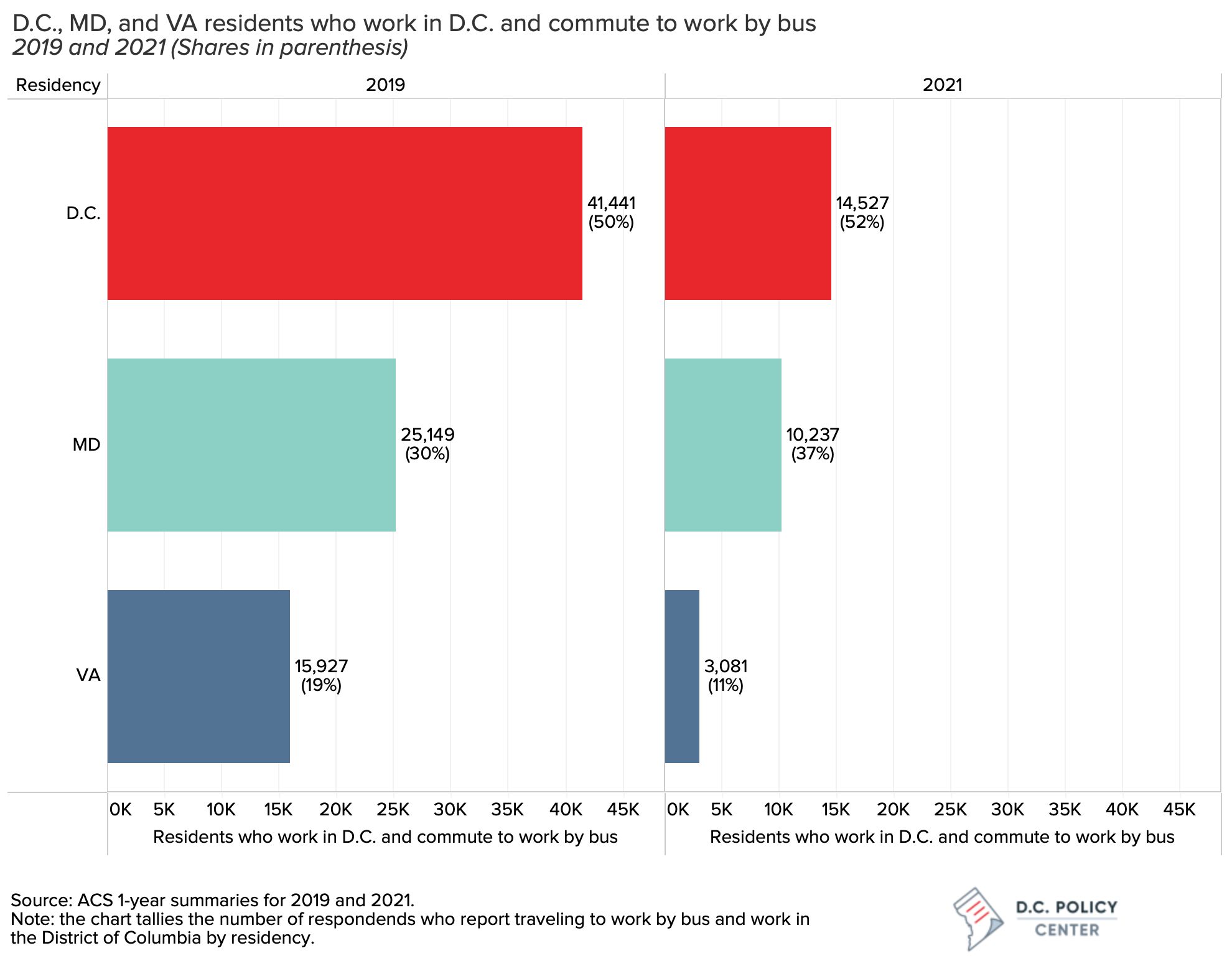

According to ACS data, half the commuting bus riders who work in the District of Columbia are non-residents. D.C. would now be subsidizing their trips back home.

What will the proposal achieve?

The bill will reduce out of pocket expenses by those who are already riding the bus. Based on the current ridership profile, metrobus riders tend to be low income (under 30K in annual income), have limited English proficiency, and be persons of color. These riders will be the main beneficiaries of fare elimination.

How does the proposal interact with jurisdictional subsidies and WMATA finances?

When a Metrobus route begins and ends in D.C., the District covers the difference between farebox revenue and operating costs for that bus. For bus routes that cross multiple jurisdictions, the gap between the farebox revenue and operating costs is covered by subsidies from the jurisdictions that contain the bus route. The subsidy formula weighs population, estimated ridership by residence, and the bus route’s presence in each jurisdiction (both measured in bus service hours and service miles) to distribute this operating gap across jurisdictions.

Since fare evasion widens the gap between fare revenue and operating costs, its burdens are shouldered by jurisdictions according to the subsidy formula regardless of where the evasion happens. At present, the fare evasion in the bus system creates an estimated loss of $8.6 million. Most fare evasion happens in D.C. (42 percent), followed by MD (34 percent) and Virginia (6 percent).

In the short run, the proposal will unlikely impact Metro finances or jurisdictional subsidies. It will simply turn farebox revenue for rides that begin in D.C. into a separate subsidy. In the long run, however, if the proposal increases ridership in D.C., especially by D.C. residents, it may increase the required subsidy for D.C. (ridership by jurisdiction is included in the formula), but not the fare revenue for WMATA. Additional service improvements (more busses, for example) will also increase the cost to D.C.

At present, fare recovery (or the amount of operating expenses fares cover) in the Metrobus system is at around 8 percent, 1 down from around 25 percent averaged over the three years prior to the pandemic.2 This makes free fares a relatively easier lift since there is already a large disconnect between ridership and cost recovery. Over time, if ridership bounces back to pre-pandemic levels, either because of normal recovery, or because of improved service, the foregone revenue will increase, making free fares a suboptimal funding mechanism. That WMATA is willing to forgo fare revenue from the bus rides that begin in D.C. signals low expectations about the future growth of ridership.

What will the proposal not achieve?

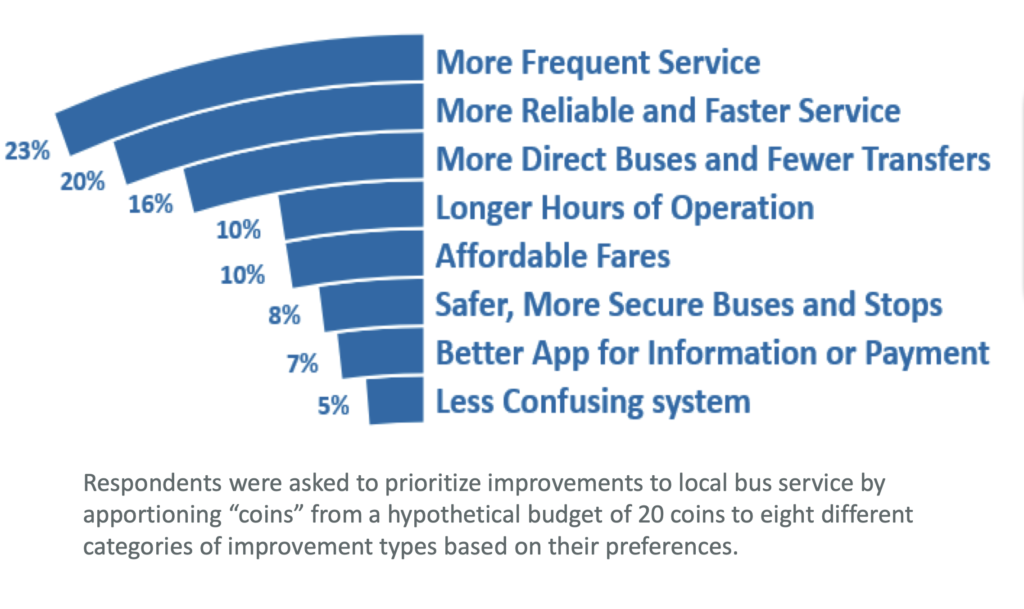

The proposal will unlikely increase ridership, without service improvements. Surveys conducted in conjunction with the bus transformation project tell us that customers are not prioritizing fares. Among eight different categories, survey respondents ranked affordable rates as a priority after five other categories, all related to service reliability and quality.

The proposal will unlikely reduce the cost of operation. One potential benefit of a fare-free system is the reduction in the cost of operation because the system will not have to put resources into fare collection. This proposal will likely have little impact on cost of operating WMATA’s bus system because fares would be collected for all bus rides that begin outside of the District of Columbia.

The proposal will unlikely revitalize downtown. Investments in turning 12 routes that serve late-night shift workers will increase ridership and help revitalize downtown. But free fares alone won’t add much to this. Experience from other systems show that when busses are offered for free, they don’t attract new people to a place—rather ridership increases because people who walk or bike (or more recently, take micro transit) simply switch to bus.3

What are some of the other potential implications?

Partial elimination of fares may create confusion and increase fare evasion elsewhere in the system. Experience from other cities show that partial elimination of fares could increase fare evasion in other parts of the system. For example, Mercer County (Trenton, NJ) fare-free demonstration in 1979 was conducted only during non-peak hours, their system sustained a loss in peak hour fares as well. A total of one-fourth (24.7 percent) of their revenue was lost from the fare-free experiment, with 4.3 percent of that loss coming from fare revenue lost during peak transit hours.4

Fare elimination may increase safety concerns. Multiple studies found that fare-free systems see increase in vandalism, theft, and disruptive or rowdy behavior by teenagers, other problems on busses.5 In some cases, these concerns drove away other passengers. Security concerns have also been shown to reduce bus drivers’ job satisfaction.6

Endnotes

- WMATA Approved Budget for FY 2023, page 37.

- WMATA Approved Budget for FY 2020, page 34.

- See, for example the report on Albany’s free bus system implemented in 1970s to revitalize downtown by Atherton, Terry J. and Eder, Ellyn S. (1981). CBD Fare-Free Transit Service in Albany, New York. Similar findings are summarized in an 2012 overview of fare free transit systems in the U.S. (Implementation and Outcomes of Fare-Free Transit Systems, by the National Academy of Sciences) and also see the experience from Tallinn, Estonia

- Summarized here.

- Reported for fare-free projects in Ashville, NC, Austin, TX, Mercer County, NJ.

- See, for example, Yaden, D. (1998) Fareless Transit in the Portal Metropolitan Area