The Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Program has provided federal funds to help cities reduce air pollution and improve congestion. Now under threat from the President’s budget, how has the program helped the District to achieve these goals?

President Trump’s recently-released budget proposal proposes cutting the Department of Transportation by 13 percent, to $16.2 billion. One target of this cut is the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) program, which provides funds for transportation projects and programs that help improve air quality and reduce congestion. The Heritage Foundation, a prominent conservative think tank, claims that CMAQ has been “focusing [instead] on transit and local trivia like bike-share programs,” and has long advocated for its removal.

CMAQ was initially introduced in the 1991 Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act and has been reauthorized in every transportation bill since its passage, including the most recent transportation bill (the FAST Act, passed in 2015). The CMAQ program has provided over $30 billion to fund more than 30,000 transportation-related environmental programs across the country as of 2015. These funds have been directed to assist metropolitan areas in reducing or maintaining concentrations of ozone, carbon monoxide, or particulate matter under the National Ambient Air Quality Standards as defined in the Clean Air Act. Projects eligible for CMAQ include advanced diesel technologies, congestion reduction, freight and intermodal improvements, car-sharing, inspection and maintenance programs, alternative fuels and vehicles, and bike and pedestrian facilities and programs.

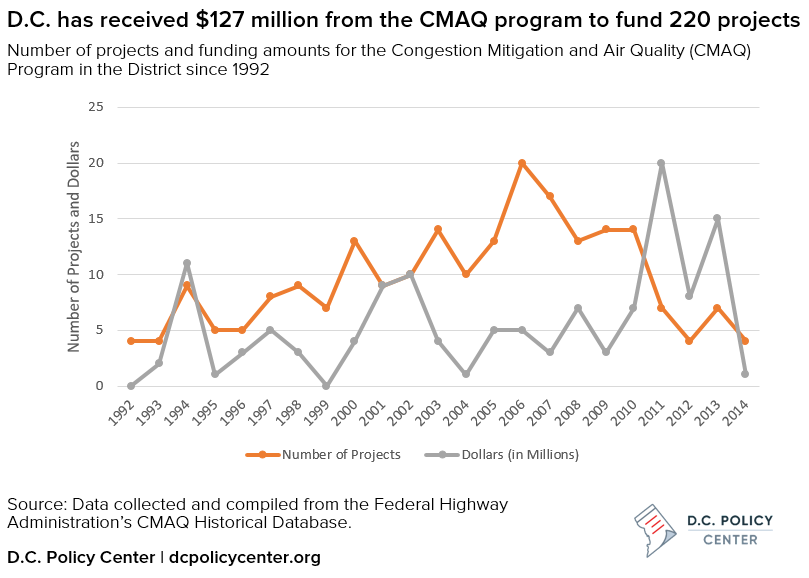

Since the inception of CMAQ, the District of Columbia has received $127 million to fund 220 projects.[1] CMAQ has provided the initial funding for programs such as Capital Bikeshare, resources for local trails such as the Riverwalk Kenilworth Trail, and supported policies that have assisted in reducing or redistributing demand on the roads when needed. The main question is whether they have addressed the core mission of the program – has CMAQ helped to mitigate congestion in the District?

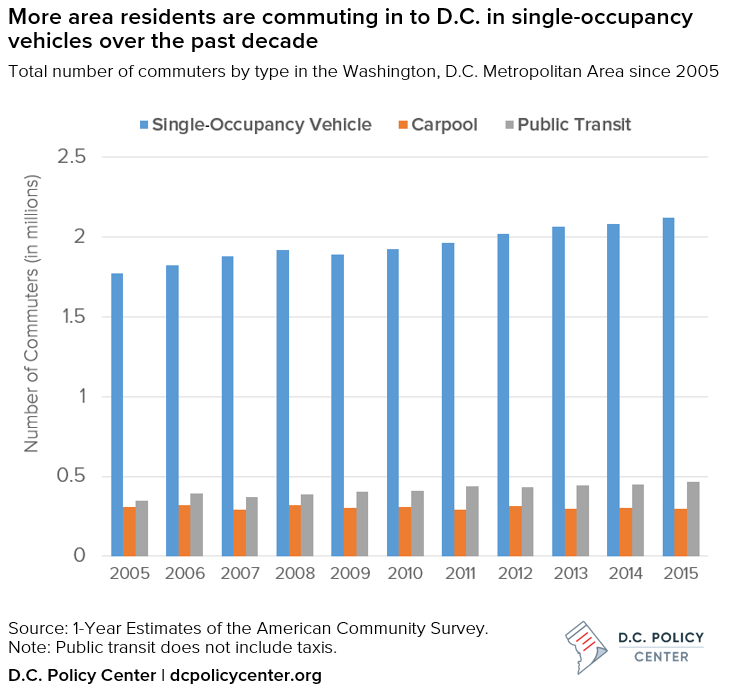

The numbers show that congestion in the D.C. metropolitan area has decreased slightly since 2010. According to data obtained from the U.S. Census’ American Community Survey, the decrease in congestion has coincided with a steady increase in the total commuter count in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. As shown in the graphic below, the single-occupancy vehicle count has increased steadily from 2005 – 2015. Public transit commuter counts have also increased in the same time frame, although they still account for a small percentage of the total number of commuters. Carpooling counts have stayed relatively flat.

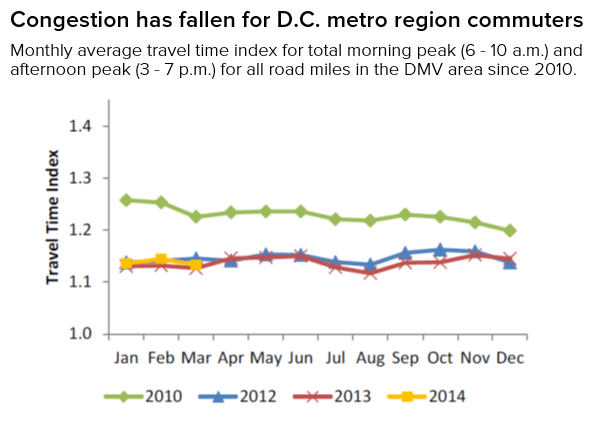

Congestion is measured in the travel time index (TTI). The higher the index, the more congested traffic is. A TTI of 1.0 means no congestion is present, while a TTI of 1.3 means that the actual travel time from one location to another is 30 percent longer than non-congestion conditions. From 2010 – 2014, the TTI decreased from an average of approximately 1.25 to an average of 1.13, according to the chart below.

|

| Chart from the National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board’s 2014 First Quarter Congestion Report. The TPB uses 2010 as a baseline measurement and compares the previous three years prior to the publishing of the report to 2010. |

The above figures show that CMAQ has contributed in part to decreasing congestion in the DMV at a time when there has been a huge increase in the District’s population. With SafeTrack and Metro woes, increased traffic from commuters is an obvious concern for the region. Individual CMAQ-funded programs such as Capital Bikeshare have had an even greater impact on their specific communities. A study conducted by Resources for the Future concluded that bike-share stations appeared to reduce congestion in surrounding areas by 2 to 3 percent from the years 2010 – 2012. It is not a large change, but when multiplying that by millions of drivers, that means a lot of time could be saved. Furthermore, roads that had speed limits of 35 miles or more per hour in areas with bikeshare stations saw the biggest decreases in congestion.

Overall, CMAQ has brought $127 million to D.C. and appears to have had a real impact on reducing congestion and improving air quality. CMAQ is an extremely flexible program, so if there are concerns that its current usage does not effectively reduce congestion or improve air quality, an alternative might be to refocus on programs that could reduce congestion even more—such as pilot programs to increase carpooling or full-time teleworking. However, ending CMAQ would likely lead to reductions in programs and services that have helped to improve air quality in the District, or would require a significant increase in transportation investment from the District’s budget simply to maintain existing efforts.