D.C. has added tens thousands of new residents in recent years, but what impact have these new residents had on local travel conditions? Fellow Will Leimenstoll looks at the District’s “Complete Streets” policy and how D.C.’s drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians have fared since the policy was enacted in 2010.

There are plenty of reasons to gripe about traveling in D.C., but if you’re lucky enough to live close to where you want to go, the city is a relatively great place to walk. According to Redfin, the creator of WalkScore, Washington, D.C. ranks as the seventh most walkable large city in the United States this year. However, walking in D.C. has not always been so pleasant. Recent improvements are in part thanks to a “Complete Streets” policy enacted by the District Department of Transportation (DDOT) in 2010.

“Complete Streets” are streets and roadways designed for the safety and convenience of drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians alike. According to the Complete Streets Coalition, over 1140 local, regional, and state level agencies in the United States have adopted Complete Street policies since the movement began in 2004. A Complete Streets policy does not mean every thoroughfare will have a cycling lane, sidewalk, or crosswalks, but in D.C. it means that all DDOT projects “shall accommodate the safety and convenience of all users.” In other words, it’s a directive not of how to design a street, but for whom to design it.

Photo source: Will Leimenstoll

The above image of Pennsylvania Avenue at 13th Street Northwest shows how a Complete Streets policy may impact roadway design. The street has multiple traffic lanes for personal cars and buses, a protected two-way bike lane for two-way cyclist traffic, parking lanes on the right, and wide tree-lined sidewalks for pedestrians on both sides. Essentially, there’s space for every kind of traveler. This particular segment of the street was redesigned in 2010, just a few months before the enactment of the Complete Streets policy, but it serves as a good example of the type of changes the policy can catalyze on the District’s roadways.

It has only been seven years since the policy was first enacted in D.C.–a short time in transportation planning–but it’s worth studying whether or not it is effectively working towards its purposes. The Complete Streets policy’s stated goals are:

- To serve the transportation needs of a diverse population.

- To deliver safe, affordable, and convenient methods of moving people and goods without harming the District’s environmental and cultural resources.

- To give residents a high quality of life that doesn’t depend on single occupancy driving.

- To promote economic activity, the movement of goods, and the quality of the natural environment.

- To expand and enhance the entire transportation network for all modes of travel.

It’s difficult to measure the District’s abilities to achieve these goals—and even if one could, the Complete Streets policy would be only one of many relevant factors to review. Many changes have occurred in D.C. in the last seven years, including recovery from a recession, significant population growth, gentrification, the arrival of Capital Bikeshare, the implementation of Vision Zero program, and the start of the Metro’s SafeTrack program. We can ask however, whether District residents’ travel is more convenient and enjoyable, greener, and safer, and from there, try to determine the impact of the Complete Streets policy specifically.

Pedestrians and cyclists are more satisfied with their commutes than they were in 2010

When looking at whether D.C. residents’ commutes are more convenient or enjoyable, there are several ways of exploring the data. Fortunately, the Metropolitan Washington Council of Government’s State of the Commute report has a treasure trove of useful data on this subject.

A whopping 97 percent of people who walked or bike to work in D.C. in 2016 said they were either satisfied or very satisfied with their commute. This is up 4 percentage points from 2010, when 93 percent of cyclists or pedestrians expressed such satisfaction with their daily trip. Pedestrians and cyclists seem even more satisfied with their commute when compared to other commuters. Only 62 percent of solo drivers expressed satisfaction with their commute in 2010, and that sunk to 57 percent by 2016. Both years, the only group that expressed less satisfaction than solo drivers was Metrorail users.

It’s hard to read too much into this data, but we do know that walkers and cyclists reported even higher commuting satisfaction in 2016 than they did in 2010—and the type of street redesigns that have been put into place in that time line up with the types of changes that lead to happier pedestrians and cyclists.

Backing this up, a national survey conducted by a bicycle advocacy group found that 54 percent of respondents would like to cycle more, and an almost equal percentage said fears of traffic collisions is what holds them back from doing so. The next section further explores how D.C.’s Complete Streets policy may be unlocking access to cycling and walking in the District.

District residents’ commutes have become greener

Biking and walking aren’t just more enjoyable modes of transportation; they also have a much lower environmental impact. In the D.C. metro area, the average cyclist commutes 4.4 miles each way, which translates to each bike commuter preventing the release of 1,845 pounds of carbon dioxide annually. If the Complete Streets policy is achieving its goals, the data should show that more people are opting to walk or cycle to work, and that the District’s greenhouse gas emissions from transportation are declining.

The 2016 State of the Commute report does indeed show that the percentage of D.C. residents who walk or bike to work rose from 11 percent in 2010 to 16 percent in 2016. Furthermore, in the region overall, 3.3 percent of commuters in 2016 walked or biked to work compared with just 2 percent in 2010. This may seem like a small jump, but prior to 2016, the percent of commuters biking or walking regionally had remained essentially flat since the State of the Commute report was first published in 2004.

The data also shows that Washington, D.C.’s greenhouse gas emissions from transportation are on the decline. The most recent Greenhouse Gas Inventory from D.C.’s Department of Energy & Environment tracked emissions from 2006 until 2013. During this time, greenhouse gas emissions from transportation declined by 15.3 percent. However, not all of these decrease can be directly attributed to the Complete Streets policy, which began in 2010. It’s likely that more fuel efficient vehicles played a major role in reducing emissions, but the shift in mode share likely played at least a supporting role.

Other variables beyond the Complete Streets policy have encouraged the shift in commuting patterns. Across the United States, people have been opting out of driving to work alone in recent years. However, by thinking about cyclists and pedestrians in roadway plans, D.C. is making it easier for people to choose not only the commute they prefer, but also the one that is best for the environment.

Are travelers safe? The data is mixed, but generally positive.

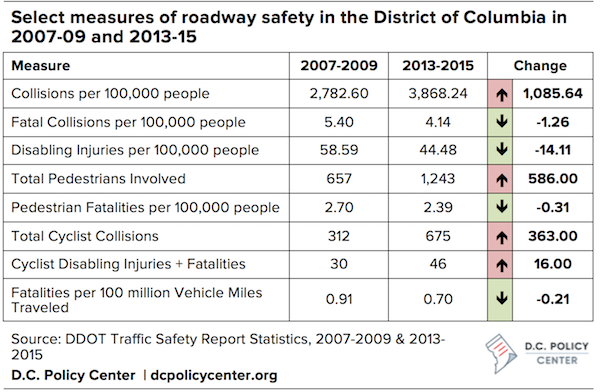

Safety for all roadway users was another stated goal of D.C.’s Complete Streets policy. D.C’s Department of Transportation has tracked safety data for years and comparing safety before and after enactment of the complete street policy sheds some light on how safe D.C.’s streets are today.

Initially, the data suggest a worsening or stagnation of traffic safety between 2009 and 2015, the most recent year of data. Overall, there were far more collisions per capita and many more pedestrians and cyclists involved in collisions in 2015 when compared to 2009.

However, some of the measures by which D.C.’s streets were safer in 2015 are especially significant. Fewer fatal collisions both total and per capita, fewer pedestrian fatalities per capita, and markedly fewer fatalities per vehicle miles traveled (VMT) are all noteworthy. Additionally, disabling injuries, (non-fatal injuries which prevent the injured person from walking, driving, or normally continuing their activities after a collision) fell significantly since 2009.

It’s especially interesting that twice as many pedestrians were involved in collisions in 2015, but the number of pedestrians who died dropped in total and per capita. So many more pedestrians involved in collisions suggests that more people started walking in this period. However, the drop in fatalities suggests that, per-mile-walked, the pedestrian fatality rate didn’t just drop, it plummeted.

At first glance, the cycling collisions seem worrisome. However, studying the data on increases in cycling commuters in the District helps determine how worried to be. According to the U.S. Census, WTOP reports, 13,000 D.C. residents regularly cycled to work in 2015 up from 5,800 in 2009. That means that, per commuting cyclist, the collision rate didn’t rise, but remained the same with 0.05 collisions per cyclist in 2010 and 2015. This is not fantastic news, but when you drill down to serious collisions, the rate of disabling or fatal collisions per commuting cyclist actually fell from 0.005 in 2009 to 0.003 by 2015.

These numbers are hardly an unequivocal win for safety, but we can still observe a slight improvement in cycling safety per capita since the introduction of the Complete Streets policy. If you factor in the 2010 arrival of Capital Bikeshare, which has since provided over 15 million rides – many of them to tourists and others who aren’t accounted for as cycling commuters – the collision rate per cyclist has likely fallen even lower.

DDOT also points out that the increase in reported collisions “could be due to an improved crash reporting system implemented by MPD and DDOT.” If this is the case, then D.C.’s roadways are indeed safer in 2015 than they were in 2009. D.C.’s improving safety is even more impressive given that national statistics show increasing roadway fatalities nationwide during this same period. Essentially, though there are more collisions—at least reported collusions—In D.C. now, both in total and per capita, the collisions are generally less severe for drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians alike, all this despite a national trend of increasing roadway danger.

Conclusion: D.C. residents’ commutes have become greener, safer, and more enjoyable

The data shows that on the whole, D.C.’s transportation system has indeed become at least somewhat greener, safer, and more enjoyable to navigate since the 2010, when the Complete Streets policy was implemented. Exactly what role D.C.’s Complete Streets policy has played in improving the commuting experience of area residents is hard to determine given the many variables that impact transportation in the District. But it is likely that the Complete Streets policy has put roadway engineers on the same page as the District’s priorities, as exhibited by the District’s Sustainable DC plan and its 2014 Move DC long-range transportation plan.

The Sustainable DC plan aims to have walking, cycling, and transit account for 75 percent of commutes by 2032, and the Move DC Plan hopes to have sidewalks on at least one side of every D.C. street and over 200 miles of bicycle infrastructure in place by 2040. The Complete Streets policy plays in important role in answering how D.C. will achieve these stated goals in the timeframe allotted. Having all parties involved in building and designing D.C.’s transportation network agree that greener, safer, more enjoyable transportation for all people is a worthy goal is a step in the right direction for the District. Whether District priorities can remain aligned across departments over the next seven years will have a tremendous impact on just how green, safe, and enjoyable transportation in D.C. will be in the future.

About the data

Data on D.C. residents’ satisfaction with their commutes is from the Metropolitan Washington Council of Government’s State of the Commute report. Data on D.C.’s greenhouse gas emissions are from the D.C.’s Department of Energy & Environment. Selected measures of roadway safety are from DDOT Traffic Safety Report Statistics for 2007-2009 and 2013-2015.

D.C. Policy Center Fellow Will Leimenstoll is an aspiring urban planner interested in how technology can help build more sustainable, economically vibrant, and equitable communities. He lived and worked in Bangkok, Thailand, Cape Town, South Africa, Auckland, New Zealand, and Durham, North Carolina before moving to the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Washington, D.C. He’s a native of Greensboro, NC and a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.