The D.C. Council is considering an education research collaborative that would carry out priority research on education in D.C. However, its current approach has one major flaw: the Council plans to place this entity under the Office of the D.C. Auditor, where it will also carry out an audit of D.C.’s education data, data management, and data collection. While both audits and research are critical to guide education policy and practice in the District of Columbia, when combined, the research will fail.

D.C. schools have improved over the last ten years of mayoral control by at least one metric: Families are flocking back to public schools, which gained 10,000 kindergarten to grade 12 students over the last ten years. However, revelations in the last year about inflated graduation rates, underreported suspensions, and enrollment fraud also exposed weak internal controls at District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) and education agencies. As a result, there is great need for more external controls, too—the type of scrutiny the Auditor is already positioned to provide under its current mandate. This office should receive adequate funding to do so and the District of Columbia’s education agencies should receive adequate resources, both financial and technical, to comply with audit requests.

Best practices of research-practice partnerships

An independent research-practice partnership—the commonly used name for research collaboratives—that generates scientific research is also necessary to identify paths for continued improvements. The research-practice partnership needs to focus on information schools need and be completely separate from audits or politics. Successful research-practice partnerships like those in New Orleans, Chicago, and New York, have buy-in from practitioners and trust of the schools and education entities where they conduct research. They collaboratively choose research topics, have an advisory board that focuses on scientific merit, and rely on external funding from foundations or federal sources instead of just the city budget.

A true research-practice partnership can ensure education data integrity, security, and availability for research. Many partnerships are hosted by a research institution or a university with a deep bench of academic researchers and expertise in cleaning, managing, and storing large datasets. For example, in North Carolina, Duke University has housed the state’s education research data center for 20 years and works on behalf of the state agency to make those data available to requestors who meet established guidelines. As a result, hundreds of dissertations, academic papers, and policy briefs have emerged based on data from North Carolina, benefiting the state and the field, and journalists and oversight agencies have had timely access to information as well. Given its core function, research talent is less likely to be recruited by the Auditor than a university or research organization.

What do existing research-practice partnerships look like in D.C. and elsewhere?

The District of Columbia should also integrate lessons learned from previous education research-practice partnerships in the city. For example, since 2011, DCPS has partnered with researchers at University of Virginia and Stanford University to examine the effect of IMPACT and now LEAP, its systems for assessing the performance of school staff and for teacher professional development. DCPS, DC PCSB, and OSSE have also shared data with the Urban Institute to study transportation to school, Mathematica Policy Research to study school choice in D.C., and many academic researchers from out of state to generate important insights in the field. In 2012, a group of researchers formed the D.C. Education Consortium for Research and Evaluation (EdCORE) based at George Washington University as a partnership between independent research firms and university-based faculty, with support from federal government and philanthropy. EdCORE released five reports on D.C.’s 2007 school reform, known as PERAA. The Auditor served as the fiscal agent for EdCORE’s work, which was mandated by the Council. DCPS and OSSE were compelled to provide data to the study and were not partners in the effort. Without strong agency buy-in and consistent financial support, EdCORE became dormant when its commissioned work ended.

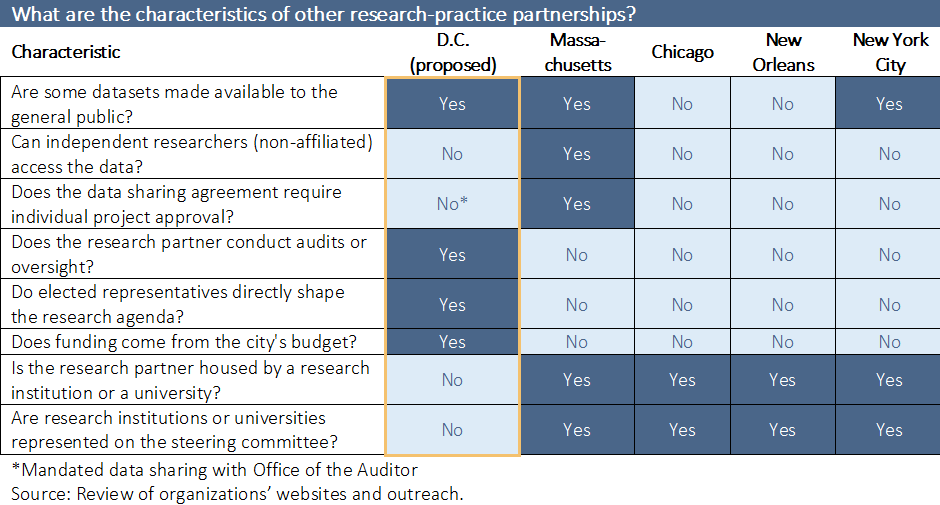

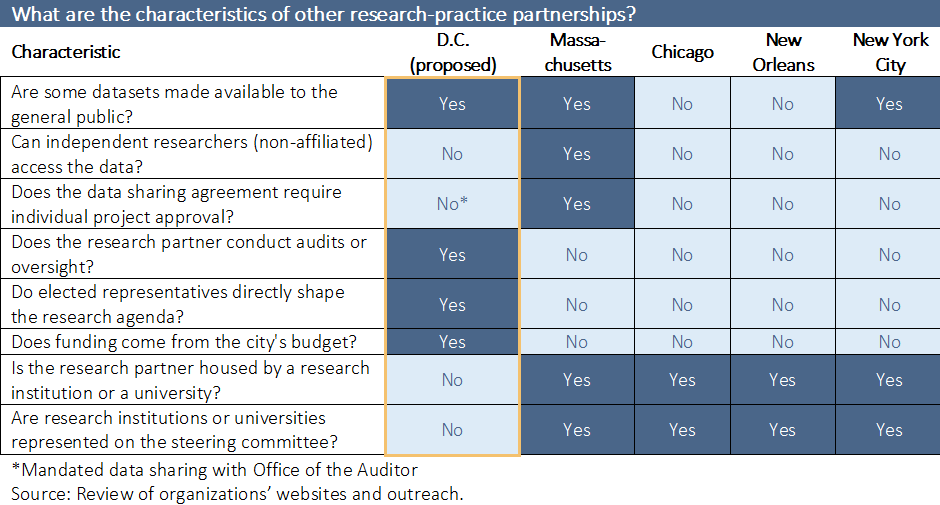

Looking at successful research-practice partnerships outside of D.C. in the table below, the proposed research collaborative differs in ways that weaken its independence. It would be the only one to have an oversight and audit role in addition to carrying out research, and the only one where elected officials can directly request studies by policy. It is also unique in that it receives all of its funding from the city instead of grants from federal sources and foundations. Lastly, it doesn’t incorporate a research institution or university as a partner or on its Advisory Board. The proposed collaborative will make some datasets available to the public, which would be a great service. In addition, it should consider a system to allow third party researchers to access data under certain conditions like the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education’s Office of Planning and Research, or the North Carolina Education Research Data Center, which primarily focuses on creating a data warehouse and making it available to requestors who meet established guidelines.

For research to succeed, it must be separate from an audit

Rigorous collaborative research can inform how educators and policymakers improve their practice; independent audits can empower oversight over such decisions—both functions are sorely needed, but best kept separated. If these two functions are combined, schools will be reluctant to participate in research wrapped up as audit and oversight. The research agenda will be shaded towards compliance rather than learning lessons for improving D.C. education outcomes. Unfortunately, the Council’s proposed path will undermine the role of research in examining what works and what positive paths D.C. can build towards providing every student with an excellent public education.