A crack cocaine epidemic and soaring homicide rates plagued the District of Columbia for a span of several years beginning in the late 1980s. In response, the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) ramped up hiring in 1989, adding more than 1,000 police officers over only about a year and a half in an attempt to get the District’s crime woes under control.

Decades later, many of those same officers are now nearing retirement or have already left. Consequently, the department has experienced a wave of retirements in recent years, but it hasn’t been able to quite keep up with all the attrition. The agency employed 3,815 sworn officers at the end of July, about the same as there were in 2004-2006.[1] Former chief Cathy Lanier had previously warned of troubles if staffing dropped under 3,800, a threshold MPD dipped below in 2015 and 2016.

The reduced staffing comes at a time when the District continues to grow and coincides with two years of elevated homicide rates. Using data MPD provided to the D.C. Policy Center, this piece will highlight recent changes in staffing and show how further retirements could reshape the department in the coming years.

As D.C.’s population climbs, police staffing declines

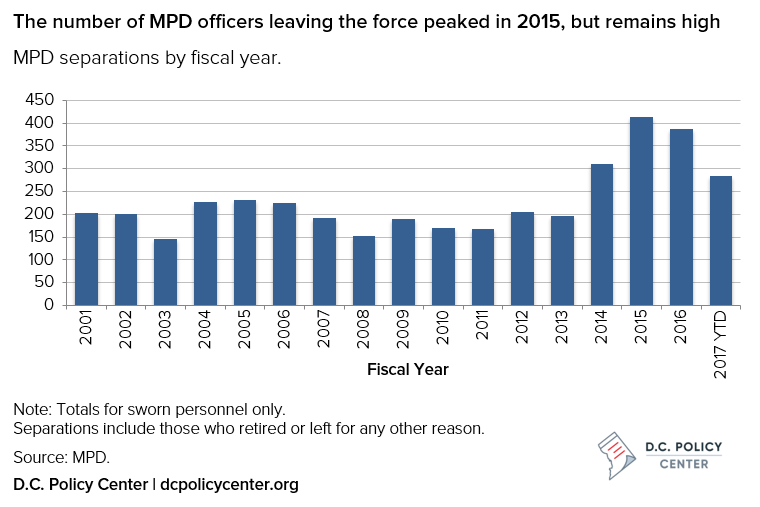

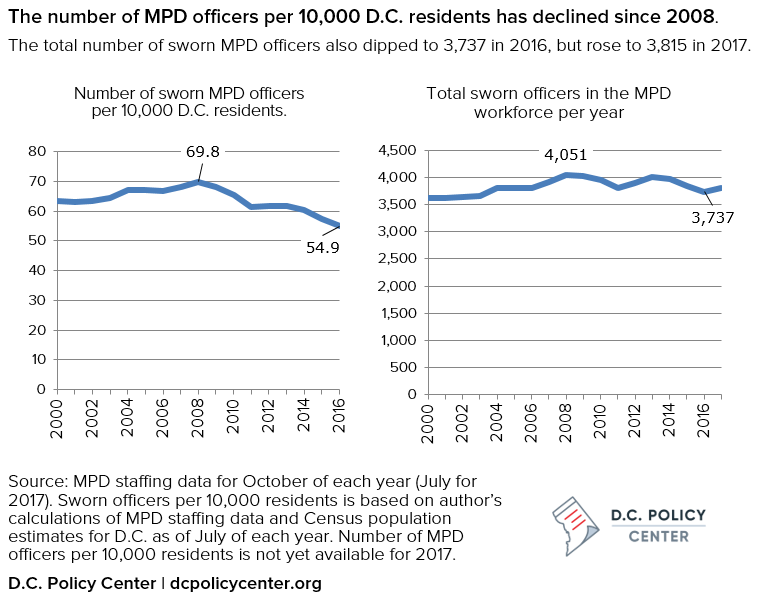

Up until around 2010, the police force had experienced mostly steady growth. But as the District was booming, staffing levels plateaued, and the subsequent uptick in retirements has since resulted in downsizing. Sworn personnel separations (officers who left the force for retirement or other reasons) exceeded hires in each of the past three fiscal years, although hiring has picked up so far this year.

MPD officer staffing, which fluctuates from month to month, is about where it was just over a decade ago. Meanwhile, over the same period, D.C.’s population grew by more than 20 percent. More recently, between 2013-2016, MPD lost a net total of nearly 300 sworn personnel as D.C.’s population continued to expand. If population growth patterns for 2017 follow prior years, there are now roughly 55 to 56 officers for every 10,000 D.C. residents, well below the most recent peak of nearly 70 officers in 2008.

Comparing Staffing Levels and Crime

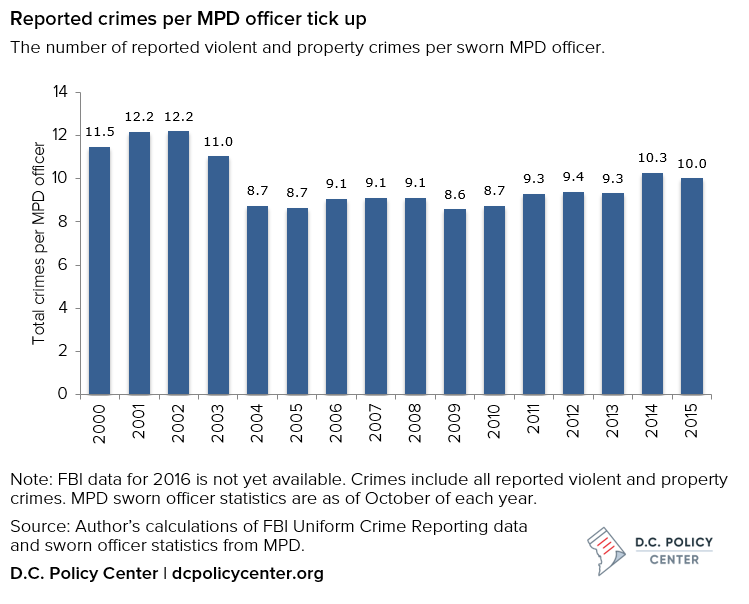

Of course, evaluating MPD staffing with per capita rates has its limitations. Another way to approximate the department’s workload is to consider how it relates to changes in reported crimes.

The latest statistics indicate that nearly every type of offense has declined from last year. Total crime so far is down 9 percent compared to 2016, according to MPD statistics as of Sept. 13. Prior to this year, the District had experienced two years of elevated homicide rates.

In 2015, MPD reported 38,443 violent and property crimes to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program. MPD employed 3,838 sworn personnel in October of that year, meaning about 10 crimes were reported for every officer.

That rate has been somewhat higher since the wave of retirements accelerated. But it’s still not nearly as elevated as prior years. Relative to crime, the agency employs more officers now than during the early part of the last decade when the District’s crime rates were higher.

However, crime alone doesn’t reflect the department’s entire workload. Examining calls for service could also prove useful, but comparable data only goes back a few years.

A Look Ahead

A large cohort of almost 1,500 officers was hired between 1989-1990; those officers could later file for retirement (and receive a pension) once they accumulated 25 years of service and were at least 50 years old. MPD has consequently experienced a wave of retirements in recent years as members of that cohort reached the 25-year mark, including 244 retirements in fiscal year 2015 and 230 in fiscal year 2016.[2]

The spike in retirements comes as no surprise—it had been a known concern for years. Back in 2011, then-police chief Cathy Lanier warned D.C. Council that a large segment of police would soon be eligible for retirement and requested additional funding to keep staffing levels steady.

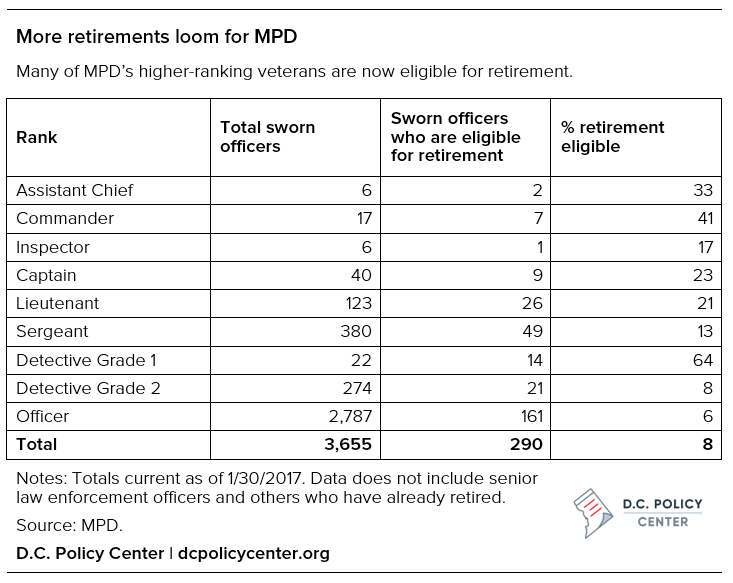

While much of the bursting of the retirement bubble is over, the losses haven’t completely subsided. According to MPD, another 290 officers–or about 8 percent of all sworn personnel–were eligible to retire as of January 30 of this year, as shown in the table below.

One area of note is MPD’s higher ranks, which could soon be hit particularly hard. Nine of the department’s 23 assistant chiefs and commanders were eligible to retire earlier this year, while more than a fifth of captains and lieutenants were similarly retirement eligible.

The bursting of the retirement bubble has put a spotlight on efforts to retain and recruit new officers.

One move that has helped ease the departures is the hiring of additional MPD civilian staff, freeing up officers working in administrative roles to return to patrols. Officers also previously worked in cell block operations, and those duties have since been transferred to the Department of Corrections.

However, competition for top candidates is intense, and D.C. police compete not only with other departments across the country, but with federal law enforcement agencies locally as well. Other departments have lowered minimum age or college credit requirements for entry-level officers. Last spring, the city started allowing candidates with two years of military service or three years of full-time law enforcement work to substitute their experience for MPD’s 60 college credit-hour requirement.

MPD’s uptick in retirements has further prompted officials to explore other ways of better retaining officers and attracting new recruits. The D.C. Council approved a measure permitting MPD to hire back retired sergeants and detectives, allowing them to receive both their pensions and a lower salary for up to five years. MPD also began offering experienced officers student loan forgiveness if they signed three to four-year obligated service agreements. And in March, the D.C. government announced a $1.6 million investment in its police cadet training program, providing a full scholarship for D.C. high school graduates to attend the University of the District of Columbia while working for MPD.

Notes

[1] Throughout this piece, “officers” refers to sworn officers with the MPD (i.e., those who have the authority to make arrests); civilian MPD employees are not included in the data.

[2] Under current policy, MPD officers are eligible to collect a pension after 25 years of service, at any age, and must retire by age 64. https://mpdc.dc.gov/page/salary-and-benefits

About the data

MPD staffing data was obtained from MPD, and can be downloaded as an Excel file here. Staffing data represents full-time sworn officers (i.e., those who have the authority to make arrests) and do not include civilians. MPD figures shown here are current as of the beginning of each fiscal year in October, but staffing totals fluctuate throughout the year. Separation totals include optional retirements, resignations, terminations, disability retirements and deaths.

Annual D.C. population estimates are from the Census Bureau (2000-2010 and 2011-2016).

Data on reported violent crimes and property crimes included in charts is from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting database and are comparable over each year.

MPD data on overall crime statistics are available here. Please note that MPD statistics may differ from what the agency reports to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting program.

Feature photo: MPD in Shaw in August, 2015. Photo by Ted Eytan (source).

D.C. Policy Center Fellow Mike Maciag currently crunches numbers and writes for Governing magazine on a variety of policy issues relating to state and local governments. He also manages the magazine’s data portal of charts, maps and other visualizations. Mike holds a master’s degree in public administration from George Mason University and undergraduate degrees in journalism and computer science from the University of Dayton.