Understanding D.C.’s criminal justice system is imperative as the city works toward racial equity, statehood, and attempts to make changes to D.C.’s system including the recent overhaul of D.C.’s criminal code. The federalization of D.C.’s criminal justice system, the direct result of the Revitalization Act, makes it uniquely complicated and has far reaching impacts on residents of the District of Columbia.

The District’s criminal justice system is largely federalized, and individuals may be held either locally by the District’s Department of Corrections (DOC). or federally by the U.S. Bureau of Prisons (BOP). What do we know about the individuals incarcerated within D.C.’s criminal justice system? How does D.C.’s uniquely federalized system impact D.C. Code offenders, and what does it mean for their access to rehabilitation programs during their incarceration?

About this series

This publication is part of the D.C. Policy Center’s Criminal Justice Week 2023, which explores various aspects of the District’s criminal justice system. Other publications in this series include:

- How D.C.’s criminal justice system has been shaped by the Revitalization Act

- Processing through D.C.’s criminal justice system: Agencies, roles, and jurisdiction

- How much would it cost to build and maintain a new D.C. prison?

- Chart of the week: Where are D.C. Code offenders housed today?

These publications are adapted from The District of Columbia’s Criminal Justice System under the Revitalization Act: How the system works, how it has changed, and how the changes impact the District of Columbia, commissioned by the District’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Council.

After the closing of Lorton Prison and final transfer of incarcerated persons in 2001, incarcerated D.C. Code offenders1 can serve sentences in local facilities if their sentence is under one year or in federal prisons run by the Bureau of Prisons if their sentence is over one year. Local facilities run by the D.C. Department of Corrections include the Central Detention Facility (CDF), also known as the D.C. Jail, and the Correctional Treatment Facility (CTF), a minimum- to medium-security facility providing behavioral and physical health care. Approximately 60 percent of people in DOC custody are awaiting trial, or in other words, have not yet been charged with a crime.

D.C. Code offenders with sentences of over one year are incarcerated in federal facilities run by the Bureau of Prisons (BOP). Differences in demographics of D.C. Code offenders and federal offenders, as well as differences in types of sentences often result in D.C. Code offenders being held in high security facilities, and sometimes in facilities where they do not have access to educational or career building programming. Additionally, while D.C. Code offenders are supposed to be incarcerated within 500 miles of the District, when possible, over 45 percent are held further than 500 miles away. Information about where D.C. Code offenders are held are contained in our next publication.

While almost all D.C. Code offenders are D.C. residents, the demographic profile of D.C. Code offenders does not match the larger District population. Almost all D.C. Code offenders are Black, male, and young. Many are incarcerated for violent crimes, and most do not have any higher educational attainment than a high school diploma.

Demographics of D.C. Code offenders in DOC facilities

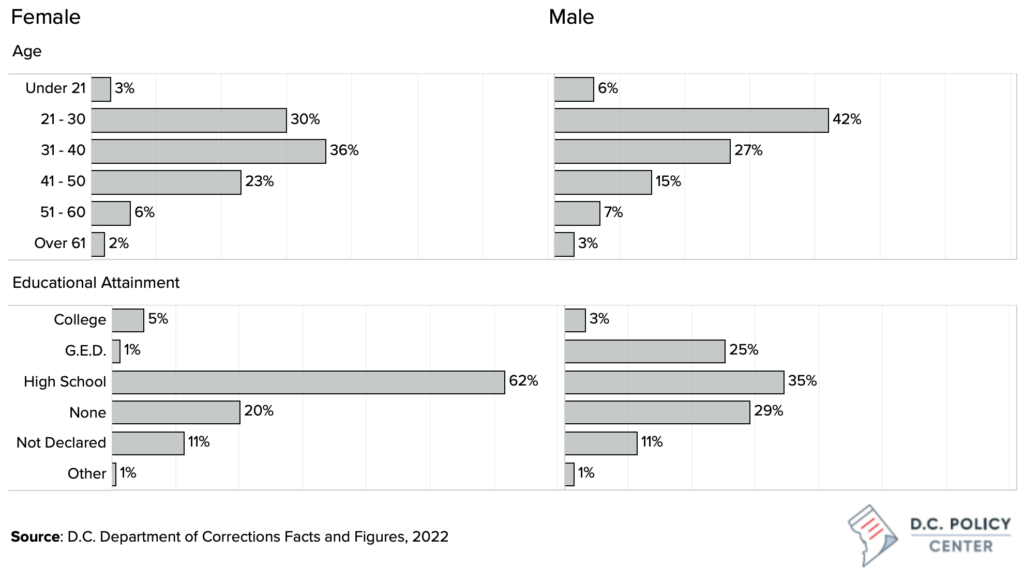

The District’s Department of Corrections collects and disseminates information on inmate characteristics, including age, gender, and employment. These data show that most of the inmates are young Black men without a college degree (Figure 1). In the Department of Corrections system, as of July 2022, the daily average population was 1,333 men and 56 women. Of this population, 289 of the men (22 percent) and 55 of the women (98 percent) were at the Correctional Treatment Facility and 1 of the women was in a halfway house. Most people in the DOC system are Black (92.9 percent), young (men were most often aged 21-30 at 41.6 percent of the population, while the plurality of women were 31-40 years old at 36.4 percent of the population), and unemployed (54 percent of men and 60.6 percent of women). Around 60 percent of both men and women in the DOC system for the third quarter of 2022 were being held in pretrial, and a little over 14 percent of each population were reincarcerated within a 12-month period, or, in other words, were charged with an additional crime.2

Figure 1. Characteristics of D.C. Code offenders under DOC custody, 2022

Demographics of D.C. Code offenders in BOP facilities

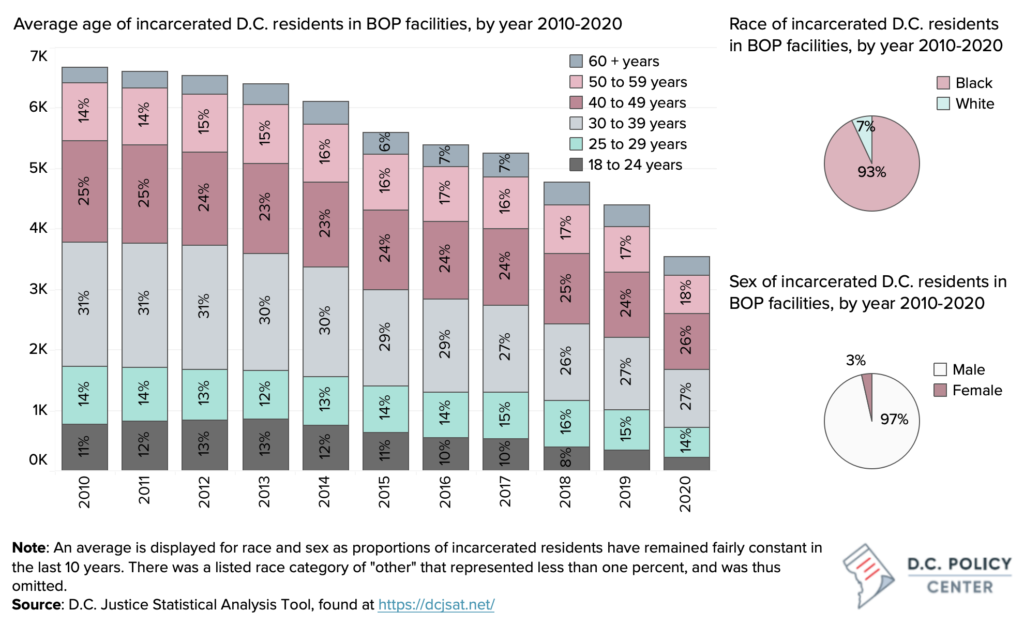

The number of D.C. Code offenders in BOP facilities has declined over time, but the share of inmates by age, race, and sex have remained relatively stable over the years (Figure 2). Slightly over a fifth of incarcerated D.C. residents under BOP custody are under the age of 30, and incarcerated D.C. residents are predominantly Black males.

Figure 2. Characteristics of incarcerated D.C. Code offenders under BOP custody, 2010-2020

Comparison to federal offenders and effects on scoring systems

D.C. Code offenders tend to have a very different demographic profile than the rest of the federal prison population. D.C. Code offenders are younger: 40 percent of D.C. Code offenders are under the age of 35, and 10 percent are under the age of 25. In contrast, only 34 percent of federal code offenders are under the age of 35.

D.C. Code offenders are also more likely be serving time for violent crimes or for violating the terms

of their parole or supervised release. Half the D.C. Code offenders serving time in BOP facilities are incarcerated for homicide, aggravated assault, or kidnapping, compared to only 3 percent of federal code offenders. In contrast, nearly half the federal code offenders are serving time for drug related charges. One in 10 D.C. Code offenders is serving time for violating their parole or supervision, whereas that share among federal code offenders is virtually zero.

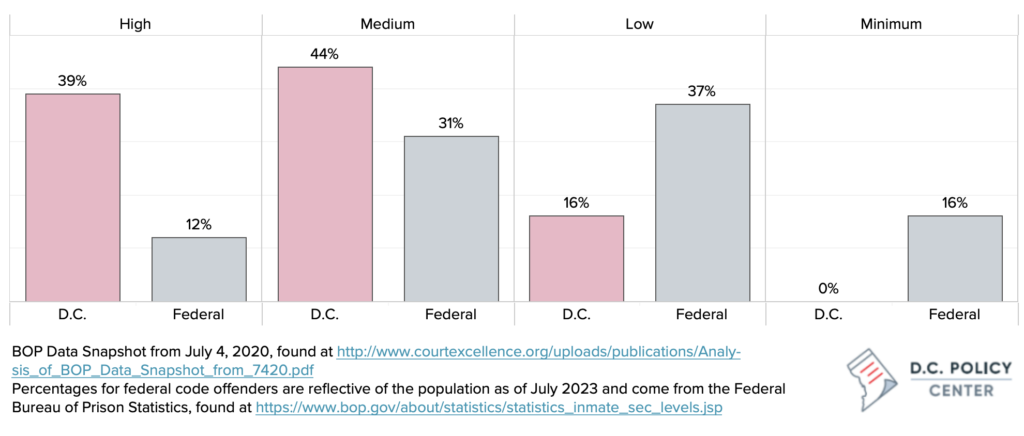

These differences in population characteristics and criminal charges matter because they feed into BOP’s scoring system for assigning inmates to prisons of different security levels. BOP’s scoring system weighs age, sentence length, and sentence type in its risk assessments, and given the nature of D.C. Code offender sentences and their age profile (multiple BOP formulas use age 25 as a cut- off point, since federal inmates in this age group are much more likely to be serving a life sentence), a larger share of D.C. Code offenders serve time in high- or medium-security prisons compared to federal code offenders.3

Data from 2020 show that 39 percent of D.C. Code offenders serve time in high-security prisons, compared to 12 percent of federal code offenders. And over half of federal offenders are incarcerated in minimum or low security facilities, compared to less than 17 percent of D.C. Code offenders (Figure 3).4 High security prisons offer less rehabilitation and education options than lower security prisons, and much more restricted environments for incarcerated persons.

Figure 3. Security level distribution for federal offenders and D.C. Code offenders

For D.C. Code offenders sentenced prior to August 5, 2000, BOP’s scoring systems may have created additional unintended consequences. BOP systems for determining security level and programming are designed for determinate sentences. However, D.C. code offenders sentenced in the pre-revitalization sentencing scheme (in 2020 this number was 611) have indeterminate sentences, or sentences with a minimum and a maximum sentence and parole eligibility following the minimum sentence served.

As such, it is possible for those D.C. Code offenders to serve sentences that are much shorter than their maximum sentence. However, because BOP operates under a system with only one length for imposed sentences, when incarcerated D.C. Code offenders were placed in BOP custody, their sentence length was recorded as the maximum sentence length. At the extreme, some D.C. Code offenders may have

life sentences as the maximum term but are eligible to reenter society following the completion of their minimum sentence. Federal inmates classified under life sentences are not assumed to reenter society and thus serve in facilities with little programming options preparing them for return. If D.C. Code offenders are grouped with federal code offenders in facilities with few or no rehabilitation programs, their success upon reentry could be impaired.5

Access to rehabilitation programs during incarceration

Research shows that access to rehabilitation and educational programs may help returning citizens rebuild their lives.6 A common concern with BOP facilities is that they don’t always offer the types of programs that incarcerated D.C. residents may need. This has been a concern for D.C. Code offenders: CIC has, in the past, recommended that BOP fill education staff vacancies and provide more opportunities to acquire a GED as well as more employment opportunities for D.C. Code offenders.7

There also appears to be a mismatch between the types of programs the United States Parole Commission considers for release decisions for D.C. Code offenders, and programs available in the facilities in which D.C. Code offenders are held. In some cases, even when programs are present in facilities, they often have high waitlists, and BOP can deprioritize incarcerated persons or render them ineligible until they are within a certain number of months of their release date.8 This is a particularly difficult situation for those who have been sentenced before August 2000 and therefore have indeterminate sentences. These code offenders do not have a determined release date until the USPC grants parole, and therefore could become precluded from many federal programs as participation in these programs requires an upcoming release date for program eligibility.

For example, one of the programs regularly required for parole release of drug offenders is the Residential Drug Abuse Program (RDAP), a program which often has waitlists of over 10,000 inmates. This program was not offered at high security facilities until 2013, and admittance is generally reserved for inmates who are at the end of their sentences, potentially excluding D.C. Code offenders with indeterminate sentences.9 In another example, USPC requires sex offenders to participate in sex offender treatment programming to be considered for parole, as treatment programs have been shown to reduce recidivism. However, sex offender programs are only offered at 2 of the total 122 BOP facilities and are only offered to inmates in the last three years of their sentence.10

When program completion is required for parole release, but the incarcerated person is not able to participate, USPC can work with BOP to ensure it is offered to that incarcerated person before the next parole hearing (typically held every three years). Additionally, in recent years, BOP has allowed some D.C. Code offenders to serve their remaining few months of their sentence in D.C. Jail rather than a BOP facility.

Conclusion

The demographic profile of D.C. Code offenders has remained relatively the same over the span of several decades. This population, however, looks significantly different than the population of the city as a whole and very different from that of federal code offenders. Differences in age, sentence type, and sentence length between D.C. Code offenders and federal code offenders influence the security levels of facilities D.C. Code offenders are held in, and therefore their access to rehabilitative programming, where in the country they are held, and their level of confinement while incarcerated. Additional information about the history of D.C.’s criminal justice system, known information about how the system currently functions, and where D.C. Code offenders are located in the country can be found in the main text of our report.

Endnotes

- Most D.C. Code offenders are D.C. residents, but also include people who do not live in D.C. but have been convicted of crimes in the District.

- D.C. Department of Corrections, “Facts and Figures, July 2022.”

- Browning, “Three Ring Circus: How Three Iterations of D.C. Parole Policy Have up to Tripled the Intended Sentence for D.C. Code Offenders.” Percentages for D.C. Code Offenders in BOP custody come from The Council for Court Excellence Analysis of BOP Data Snapshot from July 4, 2020, found at http:// www.courtexcellence.org/uploads/publications/Analysis_ of_BOP_Data_Snapshot_from_7420.pdf.

- Percentages for D.C. Code Offenders in BOP custody come from The Council for Court Excellence Analysis of BOP Data Snapshot from July 4, 2020, found at http:// www.courtexcellence.org/uploads/publications/Analysis_ of_BOP_Data_Snapshot_from_7420.pdf. Percentages for federal inmates are reflective of the population as of July 2022 and come from Federal Bureau of Prison inmate statistics, found at https://www. bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_age.jsp.

- Browning, S. (2016). Three Ring Circus: How Three Iterations of D.C. Parole Policy Have up to Tripled the Intended Sentence for D.C. Code Offenders.

- See for example the 2016 report from the Charles Colson Task Force on Federal Corrections available at https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/ publication/77101/2000589-Transforming-Prisons- Restoring-Lives.pdf.

- District of Columbia Corrections Information Council, “USP Victorville Inspection Report.”

- For example, applications for the Residential Drug Abuse Treatment Program (RDAP) must be within 36 months of their release date. This same requirement is in place for many other programs include sex offender treatment. Ellis, A. and Bussert, T. “Residential Drug Abuse Treatment Program.” Rodd, “D.C.’s Broken Parole System”

- RDAP eligibility information can be found at Council for Court Excellence. (2020). “Analysis of BOP data snapshot from July 4, 2020 for the District Task Force on Jails & Justice.”

- Rodd, “D.C.’s Broken Parole System.”