Following years of improvement in learning outcomes in D.C., COVID-19 and a year of virtual learning had negative impacts on student achievement and wellbeing. High-impact tutoring (HIT) emerged as one strategy to accelerate learning in D.C. and across the country. This type of tutoring aligns with research-backed guidelines and is concentrated, consistent, and stresses the importance of building strong tutor-student relationships.

This report examines how D.C.’s implementation of HIT represented an immense coordination effort across systems-level actors and organizations, local education agencies (LEAs), schools, and tutoring providers in its first year of implementation. While it is difficult to precisely assess the scale of HIT in D.C., it is clear that a majority of LEAs used it as part of their strategy to recover from the impact of the pandemic. Findings from a D.C. Policy Center questionnaire found that descriptions of common tutor characteristics, sessions, and approaches generally aligned with best practices and definitions for HIT established by D.C., suggesting a collaborative approach was successful to lay the foundation for scalable, citywide HIT. While HIT ended up being a common strategy to address disrupted instruction and COVID impacts for a subset of students as an intensive support, there is room to scale up student participation at the school level from this first year of adoption. Moving forward, systems-level actors will continue to evaluate their approaches and expand implementation.

Quick Links

Introduction

In D.C., learning outcomes for public school students had been improving for over two decades.[1] Then, in March of 2020, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic transitioned all students to distance learning and ended school year 2019-20 at least a month early.[2] The next year, 79 percent of students learned virtually for the entire year. Their remaining peers returned to schools for in-person learning for at most one day a week.

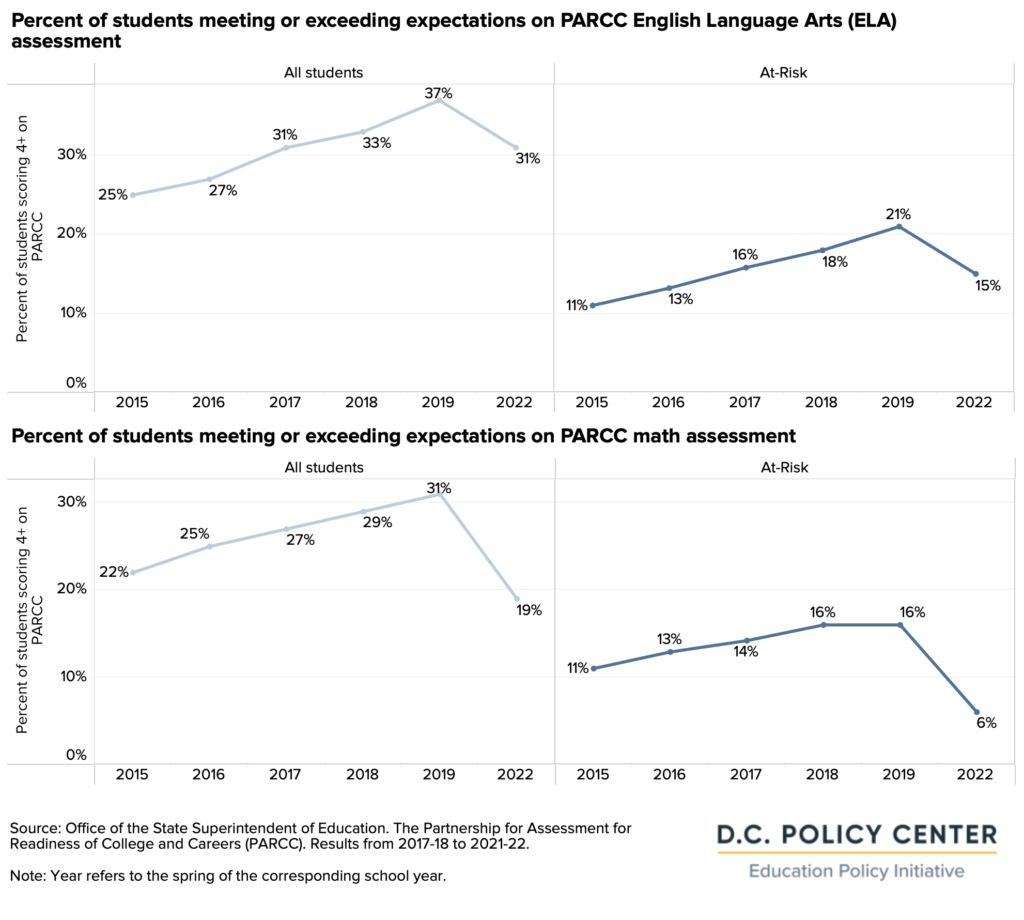

School closures and a virtual school year had negative impacts on learning as well as student wellbeing.[3] Results from the state assessment for school year 2021-22 show that both English language arts (ELA) and math proficiency rates were lower in 2022 compared to 2019, the last year that PARCC was administered before 2022. ELA proficiency declined from 37 percent to 31 percent (6 percentage points), and math proficiency declined from 31 percent to 19 percent (12 percentage points.) These are the same results as five years ago in ELA, and lower than results for math in the first year of PARCC seven years ago, suggesting that the system has lost most of the gains it had made prior to the pandemic. Students who are designated as at-risk had even lower proficiency rates—just 15 percent were proficient in ELA and 6 percent were proficient in math.[4]

Given this learning loss, when D.C.’s public school students returned to in-person learning in school year 2021-22, focus sharpened on recovering from the pandemic’s impact on student learning. High-impact tutoring (HIT) emerged as one strategy to accelerate learning in D.C. and across the country. One analysis suggests that two-thirds of the nation’s largest school systems planned to use some federal recovery funding designated for education, known as Elementary and Secondary Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds, to implement tutoring and academic coaching.[5] These activities represented at least 3.3 percent of ESSER spending across the districts that reported their COVID spending plans. While this is a small share of recovery funds that have been deployed to meet many different needs, it is nonetheless a substantial investment in a new approach.[6]

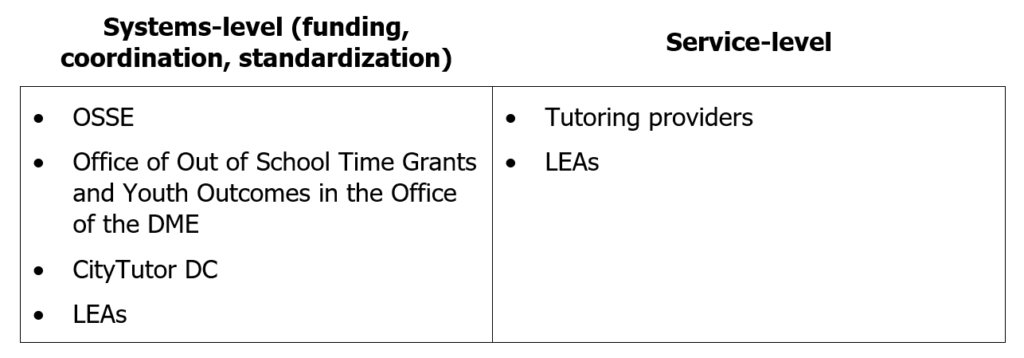

In school year 2021-22, Local Education Agencies (LEAs)[7] implemented HIT with support from systems-level entities. At the LEA level, schools who chose to use HIT as a learning acceleration strategy designed an approach to fit their needs, managing either their own staff or partnering with an external provider to deliver tutoring sessions. At the systems-level, the Office of the State Superintendent for Education (OSSE) and the Office of Out of School Time Grants and Youth Outcomes in the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education (DME) set standards and provided federal recovery funding through a grant to tutoring providers. CityTutor DC—a coalition of schools, community-based organizations, civic partners, and other stakeholders—coordinated HIT efforts and supported HIT with philanthropic funding.

In Continuous Education Plans (CEPs) for school year 2021-22, LEAs serving 89 percent of students in pre-kindergarten through grade 12 reported that they intended to implement HIT,[8][9] making it important to take stock of the first year of implementation. To do so, the D.C. Policy Center reviewed publicly available information and administered a questionnaire to find out more about how systems-level actors, LEAs, and providers describe HIT across D.C.’s public schools in school year 2021-22.

What is HIT, and how is it different from tutoring generally?

HIT, which is intended to address unfinished learning, has very specific qualities that are different from other tutoring programs. For school year 2021-22, OSSE provided the following definition for HIT:

- Provided at least twice a week for at least 90 minutes per week for students in grades 2 through 12 and at least 60 minutes for students in pre-kindergarten through grade 1;

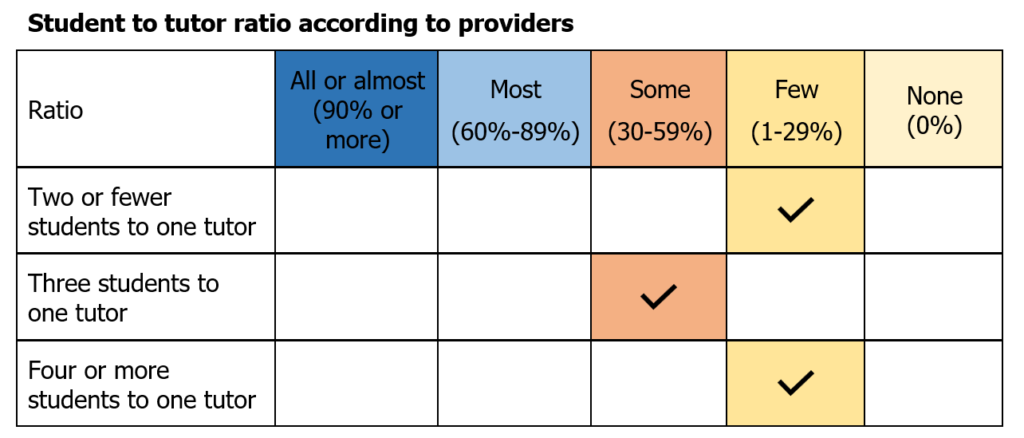

- Has a maximum student-to-tutor ratio of three students to one tutor; and

- Is focused on English language arts (ELA) or math subjects.

CityTutor DC’s definition for HIT allowed groups of up to four students, and in July of 2022, OSSE updated its definition to the same.[10] Standards for HIT developed jointly by OSSE and CityTutor DC include that it should be based in trust, focused on tutor effectiveness, supported by high-quality curriculum, occurring frequently, organized in small groups, data-driven, and collaborative with schools.

These definitions and standards are very similar to those established by the National Student Support Accelerator, which translates research on HIT into guidance and resources on effective implementation. While HIT has been found to be an effective strategy to accelerate learning, it is not necessarily a wide-reaching intervention that all students receive. Rather, HIT is integrated into a larger continuum of supports that students receive beyond classroom instruction. The number of students who receive HIT depends on the goals of the school district or education system. Any HIT offerings should align with the schools’ core curriculum as well as other interventions offered to students.

What sets HIT apart from traditional tutoring is that schools (and not parents) decide on student participation and costs are not paid for by families but by public—and in the case of D.C., also philanthropic—resources.

This analysis examines what HIT looked like and identifies key logistical constraints that emerged in establishing a large complementary system of learning supports for students. Our review of available information and analyses of responses to a questionnaire administered to LEAs, providers, and systems-level actors shows that HIT occurred in many schools as an intensive intervention and required a lot of coordination in its first year of implementation.

Summary of findings

It is extremely difficult to set up new systems of student support where many parties must work together. Our main finding is that systems-level supports from OSSE and CityTutor DC helped successfully launch HIT, and HIT was widely adopted by schools as a strategy to accelerate learning. It is difficult to know exactly how many students received HIT through school year 2021-22. The main challenges with HIT were tutor recruitment, scheduling, and student attendance. The key takeaways from this report are below.

A large number of actors quickly came together to organize, standardize, and provide HIT. While schools implemented HIT, they received system-level supports and funding from both the government (OSSE) and the community (CityTutor DC).

- OSSE prioritized having a systematic and strategic approach to help define, strengthen, and expand access to HIT.

- CityTutor DC quickly launched to strengthen D.C.’s tutoring force, build capacity for innovation around HIT, support HIT and learning out of school, and establish HIT networks of providers and schools.

HIT was intended to reach a subset of students within an LEA as an intensive intervention.

- In school year 2021-22, at least 20 out of 26 Local Education Agencies (LEAs) that responded to a D.C. Policy Center questionnaire used HIT. These LEAs collectively represented 76 percent of public school enrollment.

- Direct funding for HIT from OSSE and CityTutor DC for tutoring providers supported between 6 to 8 percent of students. Some LEAs also organized in-house HIT (and paid for it with their ESSER funds). District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS), for example, planned to reach 5 to 10 percent of students with HIT as part of their system of supports.[11] It is possible that there was some overlap in students served by outside providers and in-house efforts.

HIT demands a high level of coordination.

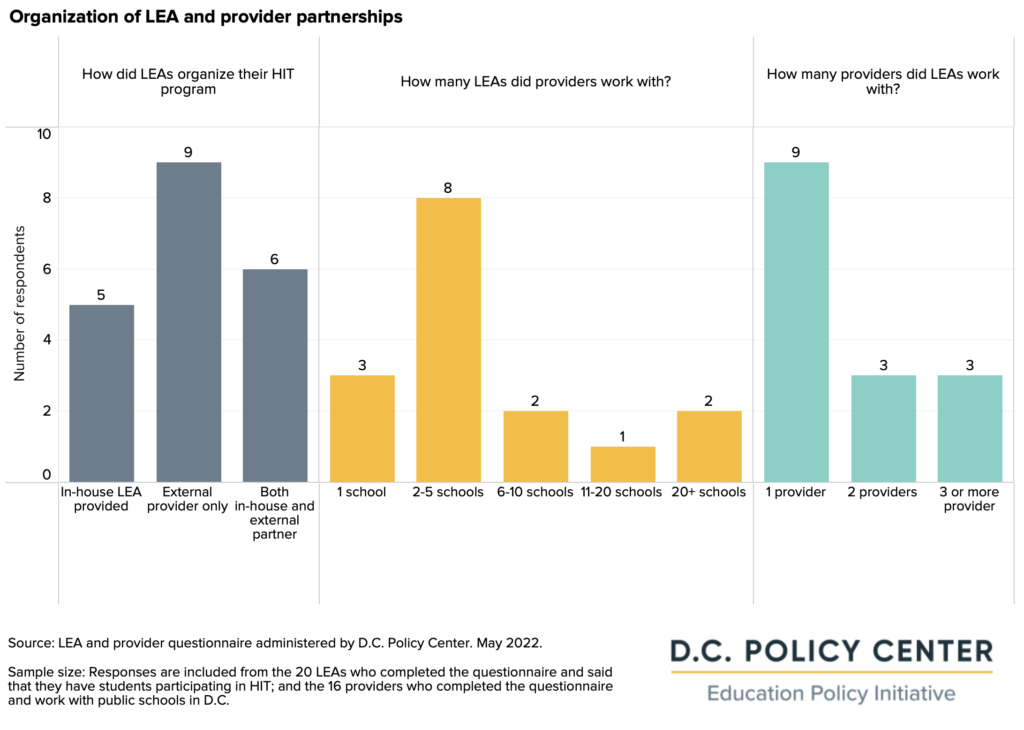

- Most providers worked with more than one school, and some schools partnered with more than one provider.

- Providers and schools had to coordinate schedules, curriculum, and goals.

There was a clear and common understanding of what HIT entailed. Provider descriptions of sessions mostly align with OSSE’s HIT definition and CityTutor DC’s standards.

- Most tutoring sessions were conducted in small groups of three or fewer students.

- Half of providers held sessions during the school day.

- All providers offered sessions more than once a week, and the majority of providers offered HIT at least 90 minutes per week for each participating student.

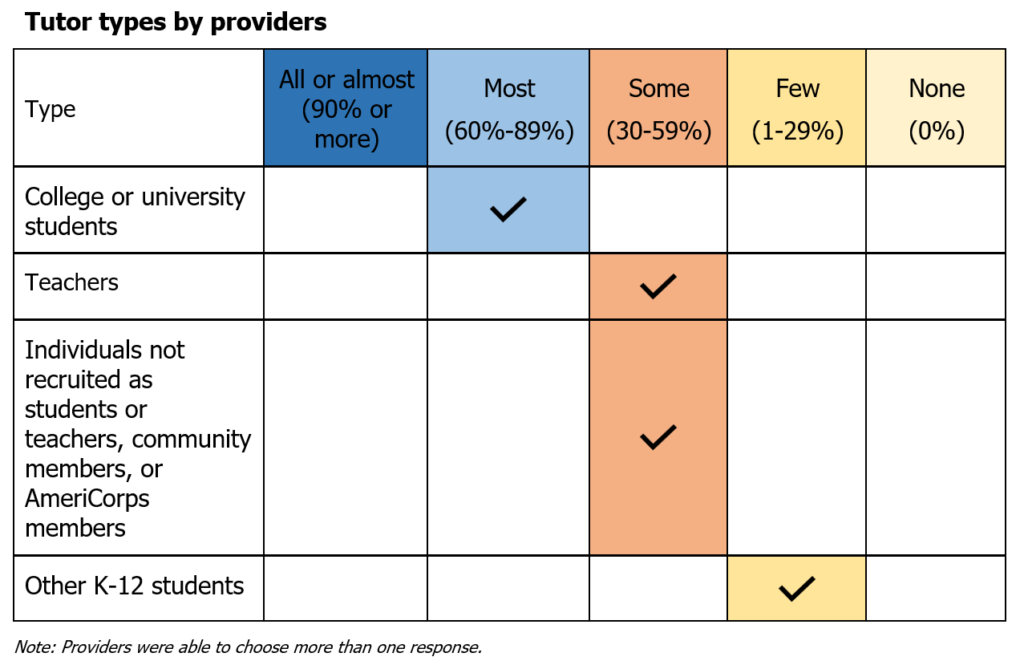

Tutors were most commonly teachers and college or university students.

- In addition, when LEAs provided in-house HIT, they mostly used their own teachers. More than half of LEAs responding to the D.C. Policy Center questionnaire reported that they provided in-house tutoring.

Tutor training was a central component of HIT across providers.

- All providers offered pre-service training.

- Almost all offered an in-service training and ongoing coaching for tutors after they have started working with students.

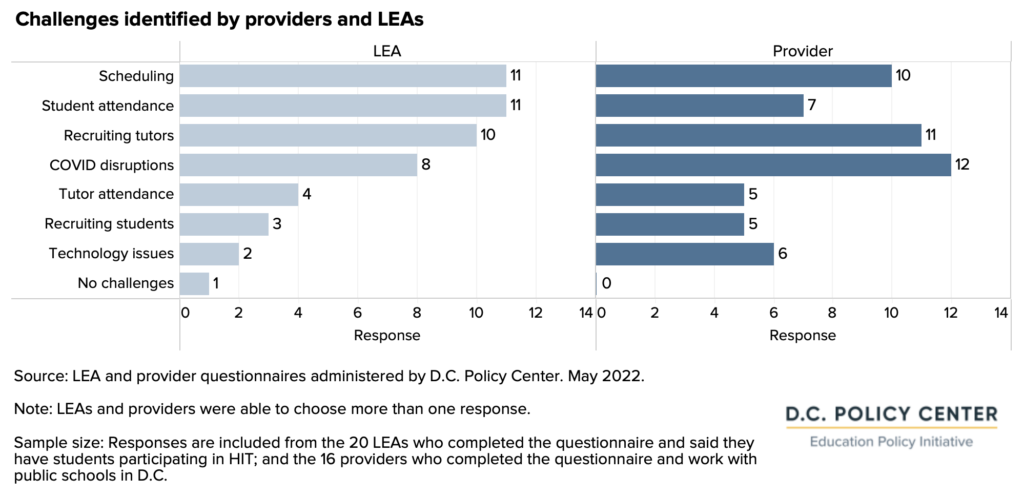

Tutor recruitment was a key challenge.

- LEAs and providers alike experienced challenges of tutor recruitment and COVID disruptions, which were both affected by largely external factors.

- Scheduling and student attendance were also common concerns.

Looking forward, the District is planning to continue to expand access to HIT in school year 2022-23 and beyond, and evaluate results.

- OSSE, LEAs, and CityTutor DC plan to continue their investments.

- More information will be available on outcomes from a study commissioned by OSSE and, separately, a CityBridge white paper on data from school year 2021-22 in collaboration with CityTutor DC and EmpowerK12.

What is high-impact tutoring?

Tutoring, when provided consistently, intensively, and by prepared tutors, can be one of the most effective strategies to improve student achievement. Meta-analyses of randomized evaluations, conducted by J-PAL[12] and Roland Fryer of Harvard University[13] show that intensive tutoring programs are associated with greater learning gains. The National Student Support Accelerator of the Annenberg Institute at Brown University[14] has identified certain elements of tutoring that tend to be present in effective programs:[15]

- High-dosage delivery (i.e., three or more sessions per week of required tutoring);

- A stated focus on cultivating tutor-student relationships;

- Use of formative assessments to monitor student learning;

- Alignment with the school curriculum; and

- Formalized tutor training and support.

The National Student Support Accelerator also recommends that HIT should be integrated into a broader strategy to address district priorities, including as one possible intervention in a larger continuum of supports, especially Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS)[16] and Response to Intervention (RTI) frameworks. Their guidance states that tutoring should not replace instruction (Tier 1), but can be offered as a more targeted, or even individualized intervention (Tier 2 or 3).[17] This means HIT is not an intervention that all students will receive.[18] While MTSS does not align directly with how students are targeted for tutoring, it aligns with the smaller percentage of students who are generally targeted for HIT —anywhere from 5 to 20 percent. Tennessee’s All Corps tutoring program,[19] for example, suggests targeting students who have demonstrated learning loss and that the program can supplement but specifically not supplant already established Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions.[20]

HIT can take many shapes. It could, for example, mean that a classroom teacher meets one-on-one with a student after school several times a week to shore up reading skills. HIT could also be an external organization partnering with a school and bringing in volunteer tutors from a local university for afterschool tutoring. Tutors can be college students, classroom teachers, community volunteers, or members of national volunteer networks like AmeriCorps. Tutoring may be held in the school building during non-instructional time, during or after the school day, or be held in an offsite location like a community center after school. Sessions could be held two times a week for longer periods or three times a week for shorter periods.[21]

The combination of factors identified above—multiple sessions a week, emphasis on cultivating relationships, assessments, tutor preparation and management, and curriculum alignment—are what differentiate HIT from other forms of tutoring.

Landscape of high-impact tutoring in the District of Columbia

To find out more about HIT across D.C. in school year 2021-22, the D.C. Policy Center collected data from LEAs, schools within DCPS, tutoring providers, and systems-level actors supporting tutoring efforts. These stakeholders answered up to 30 questions that inquired about tutors, students, tutoring sessions, and reflections on implementation. The questionnaire was circulated in May and June of 2022. OSSE and CityTutor DC supported dissemination efforts with outreach to their partners.

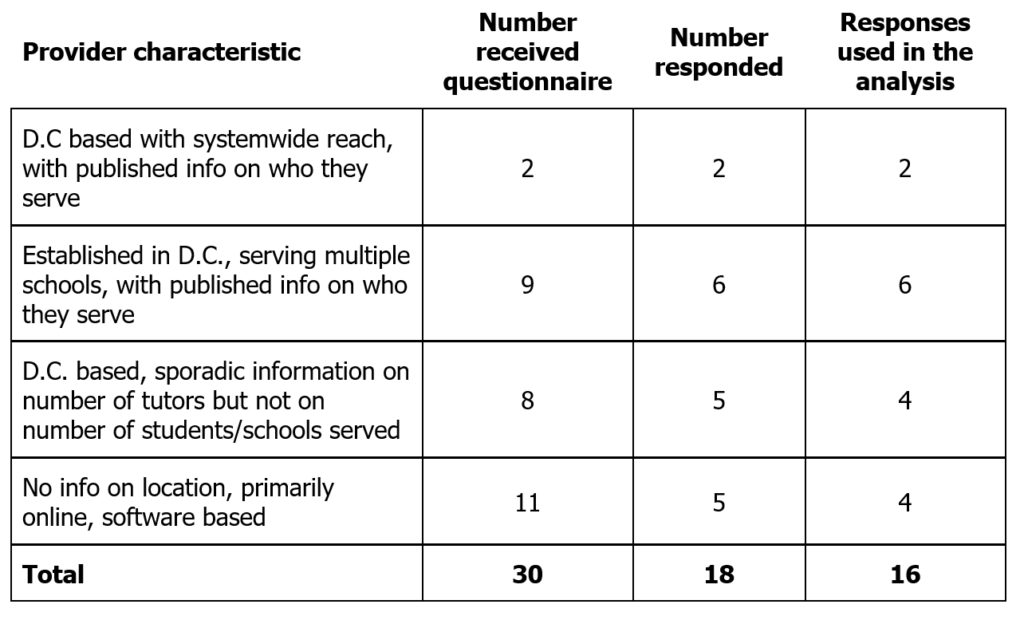

Twenty-six out of 60 LEAs responded to the HIT questionnaire, representing 80 percent of students enrolled in D.C.’s public schools. Twenty of these 26 responding LEAs provided HIT. Eighteen out of 30 active tutoring providers in D.C. responded to the questionnaire, including the two largest providers.[22] Sixteen out of the 18 providers responding reported partnering with D.C.’s public schools to provide HIT. For more information on respondents, see Appendix A. For detailed findings on responses, see Appendix B.

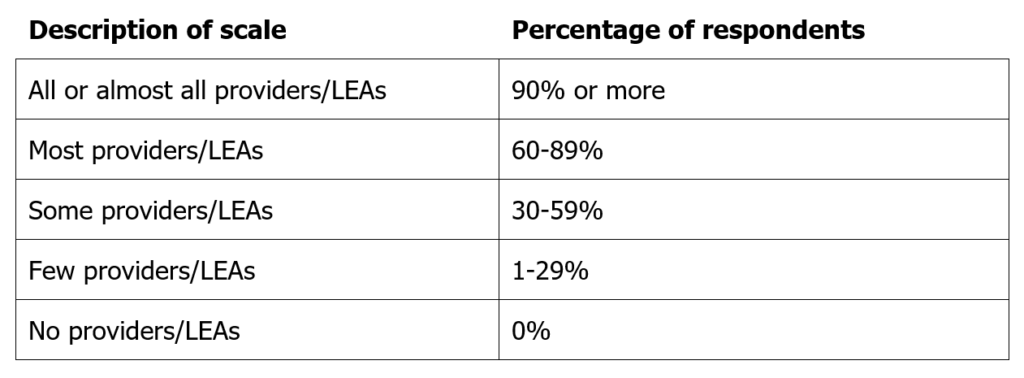

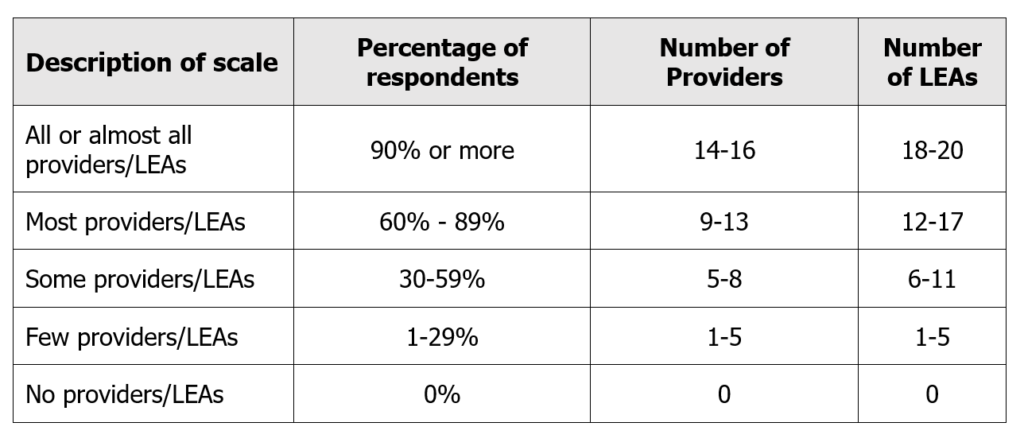

Throughout the report, findings are qualitative in nature and described on a scale based on the frequency of each response option.[23] These scales refer to the number of respondents per question and are not weighted by provider reach or LEA size. Responses are self-reported and do not measure implementation.

Findings from D.C. Policy Center HIT questionnaire

HIT was supported at both the systems-level and at the LEA, or service, level. Systems-level actors established standards and definitions, and provided funding, both to HIT providers and to LEAs, so they could initiate new or expand existing HIT programs. They also created resources and communities intended to enhance HIT efforts. At the service level, LEAs funded providers themselves and worked with providers who were funded by systems-level actors. LEAs also provided HIT with their own staff.

Systems-level supports for HIT created standards, coordinated action, and created practical tools for implementation

At the systems-level, HIT was supported by OSSE, the Office of Out of School Time in the Office of the DME, and CityTutor DC. Together, they provided approximately $5 million of combined philanthropic and public funding directly to 17 HIT providers[24] as well as a small subset of schools for the first year of implementation in school year 2021-22.[25] In the fiscal year 2022 budget proposal, OSSE allocated over $10 million of ESSER and American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) federal funds to enhance HIT, with a plan to dedicate $39 million in total to HIT through fiscal years 2022, 2023, and 2024.[26][27]

These entities also provided non-monetary supports. OSSE partnered with CityTutor DC to provide updated guidance on high-impact tutoring for LEAs.[28] CityTutor DC formed a coalition of schools, community-based organizations, civic partners, and other stakeholders to expand access to HIT.[29] Specifically, CityTutor DC strengthened D.C.’s tutoring force, built capacity for innovation around HIT, supported HIT and learning out of school, and established HIT networks of providers and schools.

Spotlight: CityTutor DC Design Sprint

To better integrate tutoring into the school day, CityTutor DC organized Design Sprints for more than 35 schools to participate in a multi-week program that supports schools in the following activities: creating a new student schedule for scaled implementation, considering an intervention block, designing a plan to strengthen the strategies to accelerate and supplement academic learning, and identifying and setting measurable student learning targets.

Source: CityTutor DC. 2022. A Citywide Approach to Acceleration: Early Lessons from CityTutorDC. CityTutor DC. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/12CdQDn2uDn6e-tMW4bWBYj3WXZ7U6yVM/view

LEAs set aside funding, and time through the school day, to deliver HIT

In addition, OSSE also released over $540 million in ESSER federal funds to LEAs that could be spent from March 2020 through September 2024, with tutoring as one of the allowable uses.[30] District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS), for example, dedicated 36 percent of the $182 million in ESSER I and II funding to spend from FY21 to FY24 on academic acceleration (including HIT) and social emotional learning.[31] LEAs can use ESSER funding to partner directly with external HIT providers or to pay their own staff to provide tutoring services. LEAs can also partner with external HIT providers that are funded by OSSE, DME, or CityTutor DC.

Examples of HIT plans

In a review of Continuous Education Plans submitted by LEAs for school year 2021-22, LEAs serving 89 percent of students reported that they had plans to implement HIT.[32] LEAs differed in the type of programming planned, or how they planned to target participating students, organize their HIT program (internally, or with a provider), and pay for HIT. The following summarizes what some of the largest LEAs included in their Continuous Education Plans.

- DCPS planned to utilize HIT as a Tier 3 intervention (targeted and individualized support), which typically serves 5 to 10 percent of each school’s population. DCPS has established partnerships with Literacy Lab and Reading Partners for elementary students and Saga Education for students in grades 9 and 10 and planned to pay for their programs with funds set aside for accelerated learning, including ESSER III-ARP funds.

- KIPP DC PCS planned to target HIT to “students most in need of academic support.” KIPP DC PCS also emphasized summer programming in 2021 provided through a combination of partnerships with Literacy Lab, Mathnasium, and other providers as well as staff members trained on HIT. KIPP DC PCS planned to invest $1.5 million in a combination of acceleration efforts.

- Friendship PCS included “intensive” tutoring as a Tier 3 support, and planned to use diagnostic performance tests to identify students for high-dosage tutoring. Two campuses were working with CityTutor to define the program for school year 2021-22.

- Several other LEAs mentioned HIT in their Continuous Education Plans as an intervention specifically for students with disabilities and English learners. LEAs planned to incorporate HIT into the school day by building time within the school schedule for tutoring-specific periods and by hiring additional staff and training staff on the appropriate intervention curriculum.

HIT reached a subset of students across at least 147 schools

HIT was a common intervention implemented across many schools, but was intended as an intensive support for a small percentage of students at each school. The student populations served by providers and in-house programs may overlap. Because the sizes of these efforts were described individually by systems-level actors, LEAs, and providers, it is difficult to know the precise scale and reach of HIT across D.C.’s public schools. Based on information collected separately from systems-level actors, LEAs, and providers, the D.C. Policy Center identified at least 147 schools out of 224 that were involved with HIT.

OSSE and CityTutor’s direct funding reached between 5,000 and 7,200 students, or up to 8 percent of students in pre-kindergarten through grade 12. In addition, more than half of the LEAs responding to the D.C. Policy Center questionnaire reported providing in-house tutoring, likely using ESSER recovery funds intended for learning acceleration. LEAs have not reported on the number of students reached through these efforts. DCPS, for example, intended to reach 5 to 10 percent of students with one-on-one or small group tutoring (between 2,300 and 4,700 pre-kindergarten through grade 12 students).[33] The total number of students reached by all actors in the District is not known due in part to a lack of consistent data on the number of students who were tutored in-house by school staff.

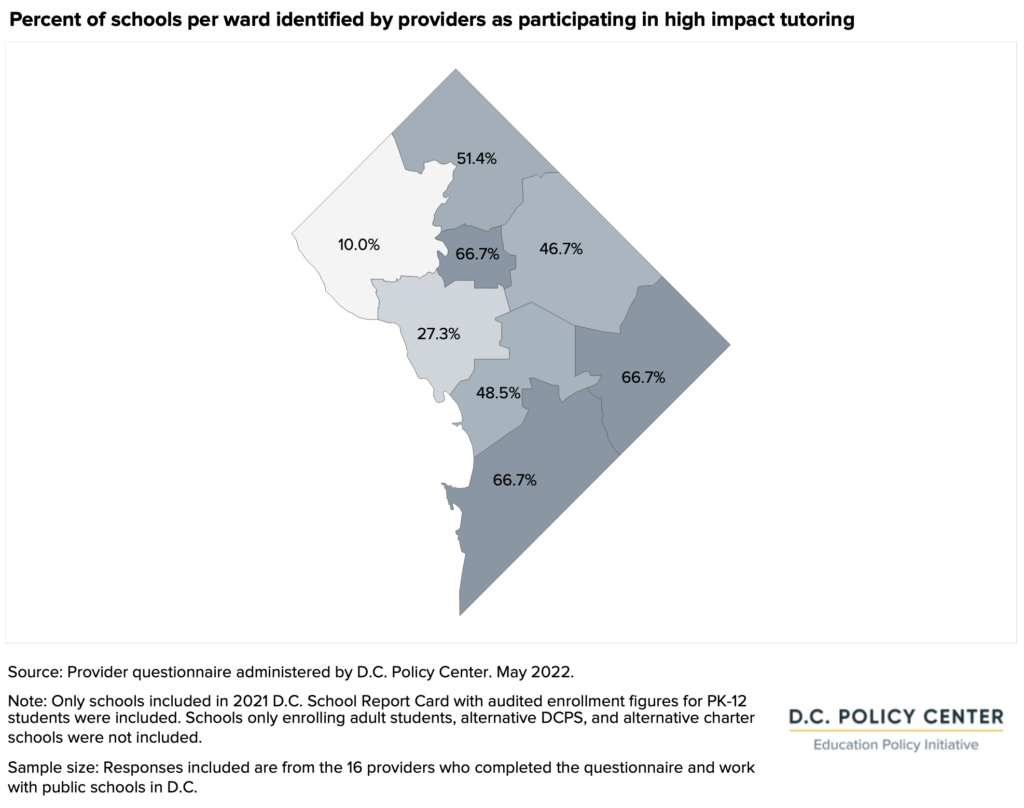

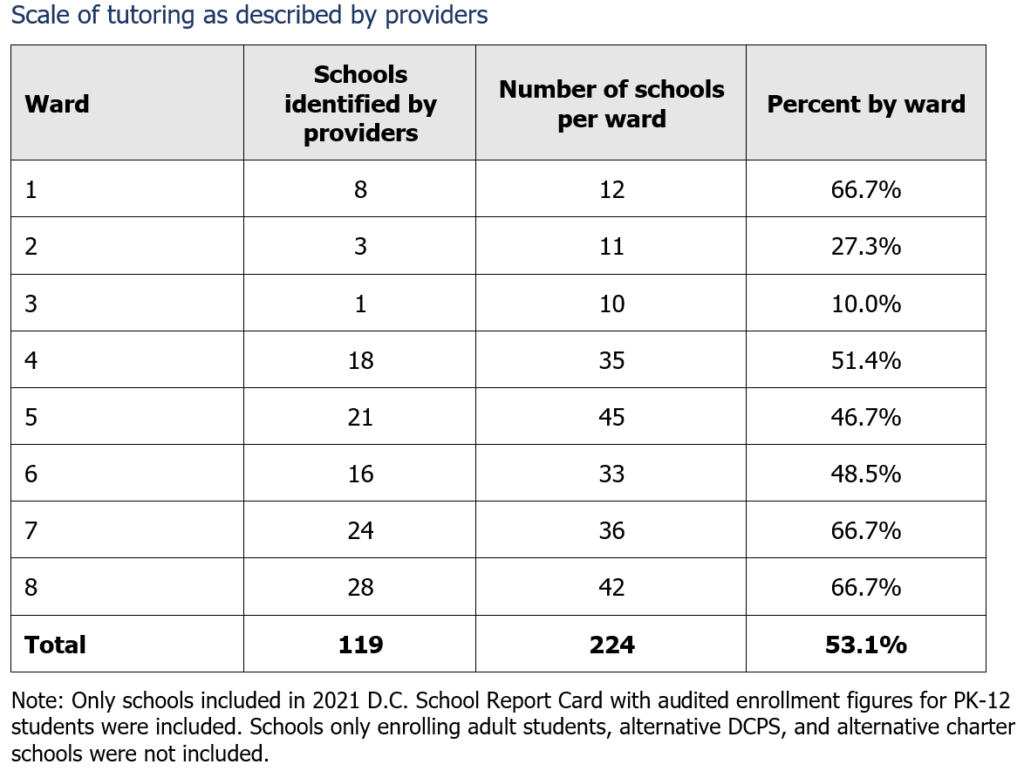

Providers were more likely to serve schools in Wards 7 and 8

The tutoring providers who responded to the questionnaire collectively served students coming from 119 out of 224 PK-12 DCPS and public charter schools in D.C. (53 percent).[34] Providers identified school campuses in all eight wards that they partnered with to provide HIT. Providers were most likely to work with schools in Wards 7 and 8, where they collectively worked with about two-thirds of schools in these wards. Providers reported working with only three schools in Ward 2 (27 percent of Ward 2 schools) and only one school in Ward 3, out of the 10 schools in this ward.

The implementation of HIT required a lot of coordination

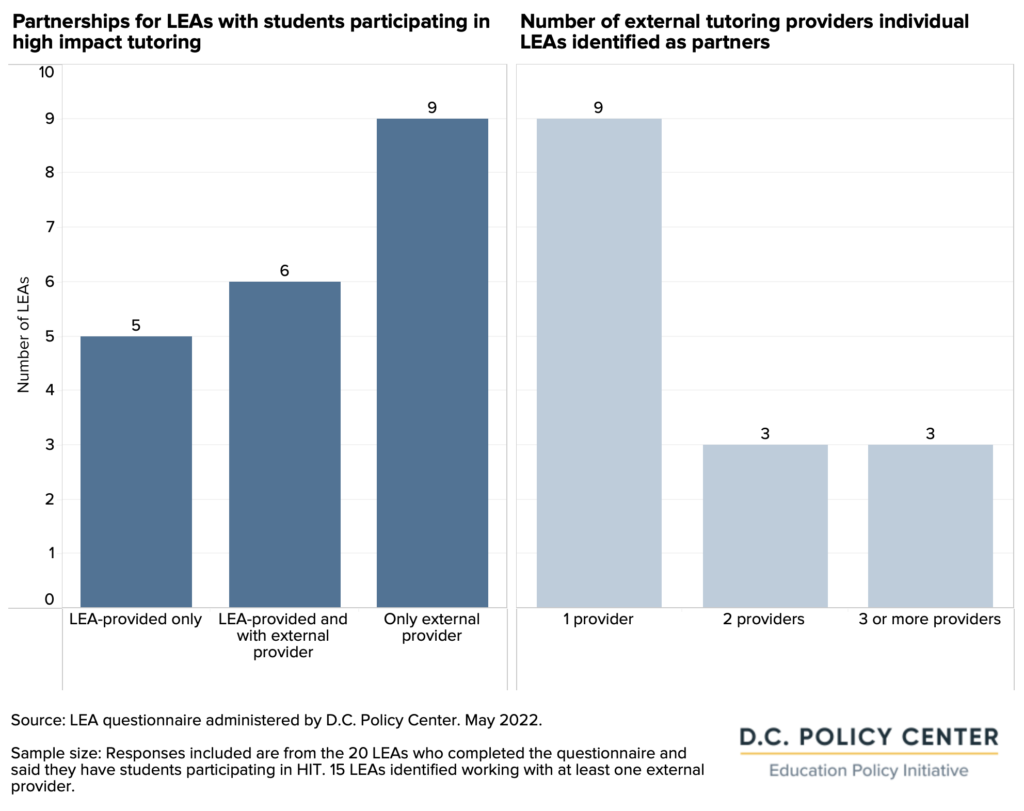

In its first year of implementation, HIT required a lot of coordination. Each school that worked with a provider had to coordinate on scheduling. Further, some schools worked with multiple providers (sometimes three or more different providers), and some schools mixed provider services with their own in-house tutoring, making coordination necessary for scheduling sessions.

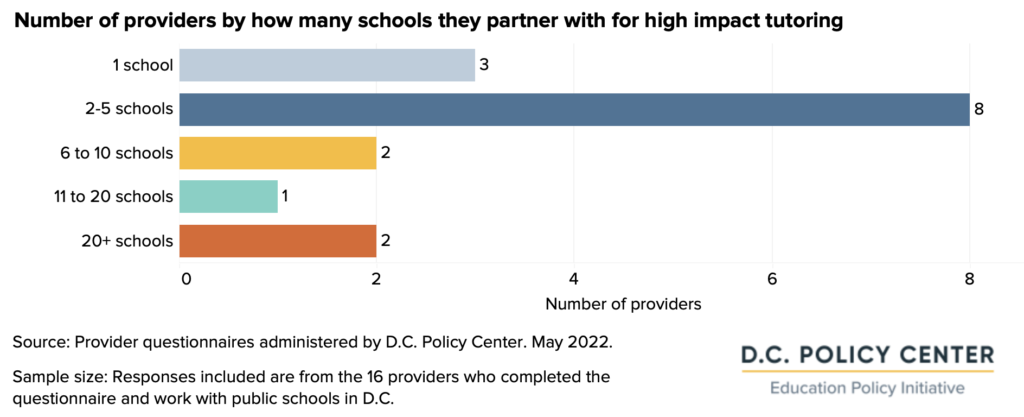

Providers are more likely to work with multiple schools ranging from one school to over 50 schools. A small number of providers operate on a small scale and work only with one school. Some providers have been able to create scale and work with six or more schools. The majority of providers who responded to the questionnaire partner with two to five schools.

Most HIT sessions involved small groups of students who met frequently during the school day

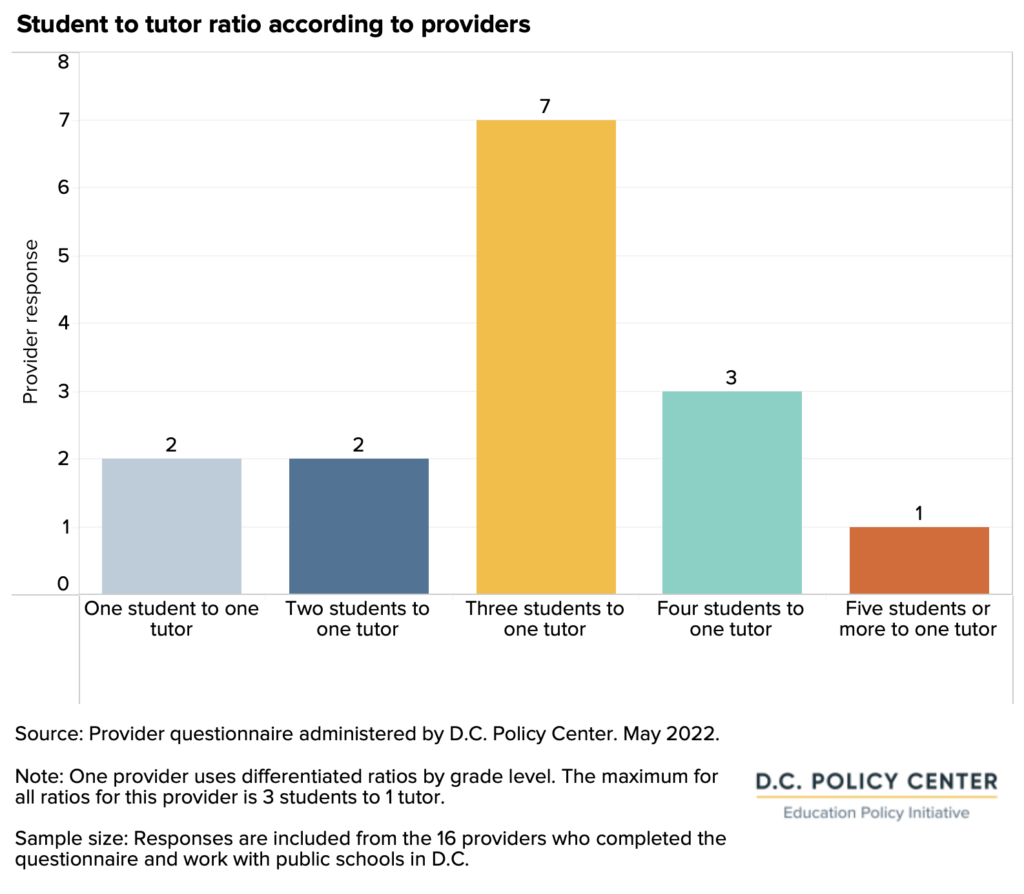

Most tutoring sessions were with small groups of two or three students per tutor instead of one-on-one. The most common student-to-tutor ratio described by responding providers was three students to one tutor. A small number of providers organized groups with two students, and a similar number organized groups with four or more students. The recommended group size in OSSE’s updated definition and CityTutor DC’s standards for HIT is at most four students.

“Students appreciated the smaller groups. We never gave students the feeling that participating in any academic support or high-impact tutoring was a negative or from a deficit framework. It was always presented as a support to accelerate their learning.”

LEA respondent

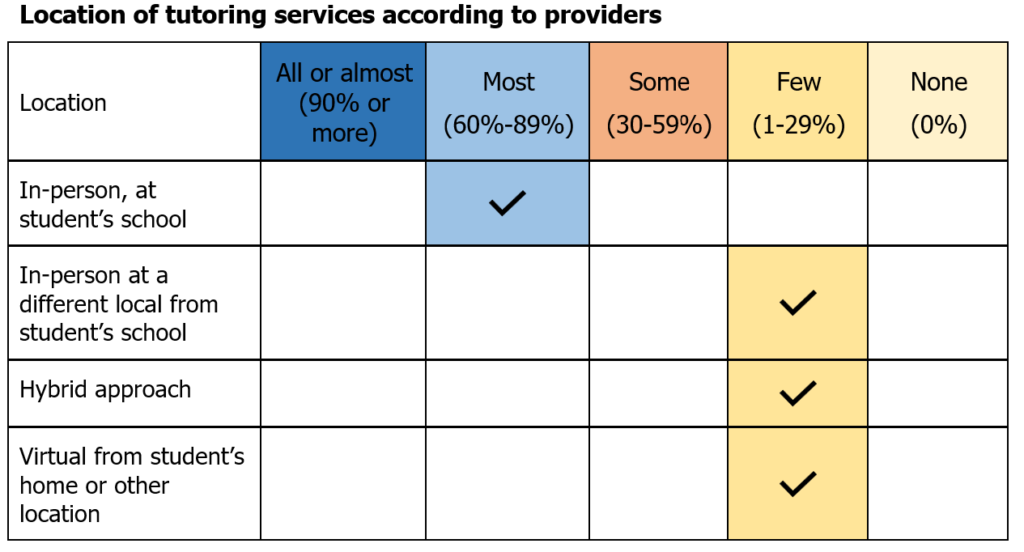

The majority of providers deliver tutoring services to students in-person at their schools. Two providers deliver tutoring services at a location different from the one where students attend school, one provides services virtually, and one provider uses a hybrid approach primarily relying on virtual software.

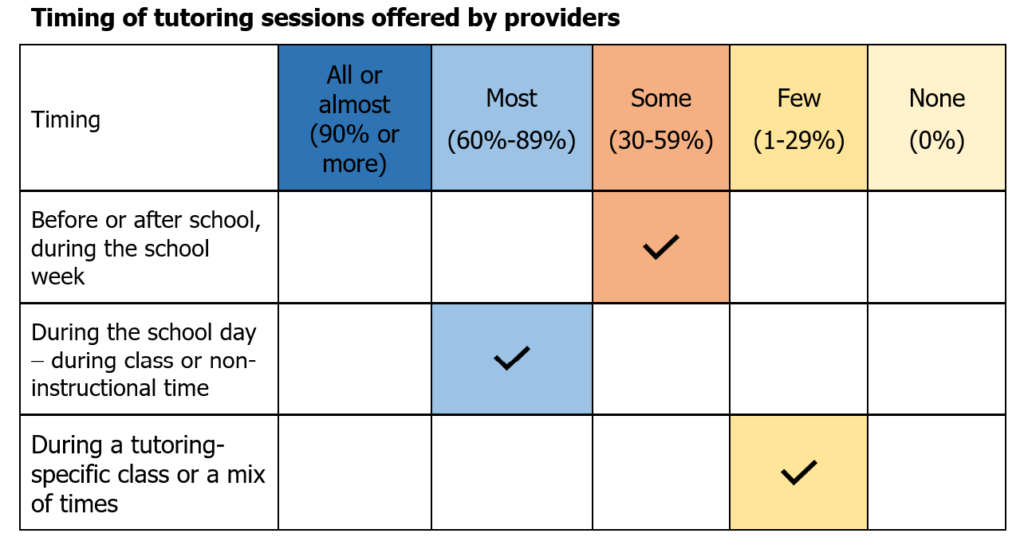

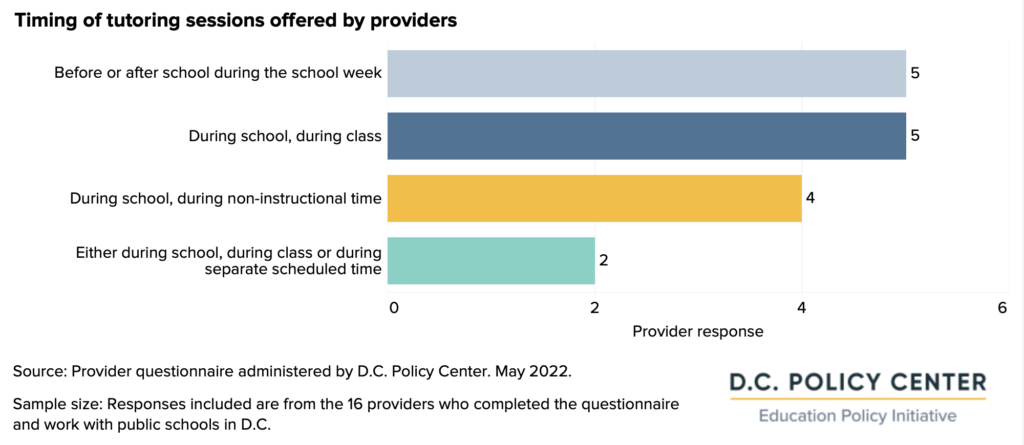

Tutoring that occurs during the school day tends to be more effective than tutoring that occurs after school or during the summer, as it means attendance is more certain and the focus is on academics.[35] When asked when tutoring sessions most often occur, providers most-commonly answered that sessions were held during the school day—with an almost even split between sessions during class and sessions during non-instructional time. Fewer providers tutored before or after school during the school week. One provider held an even mix of during class, during non-instructional time, and before or after school. One provider offered tutoring during a scheduled period specifically set aside for tutoring.

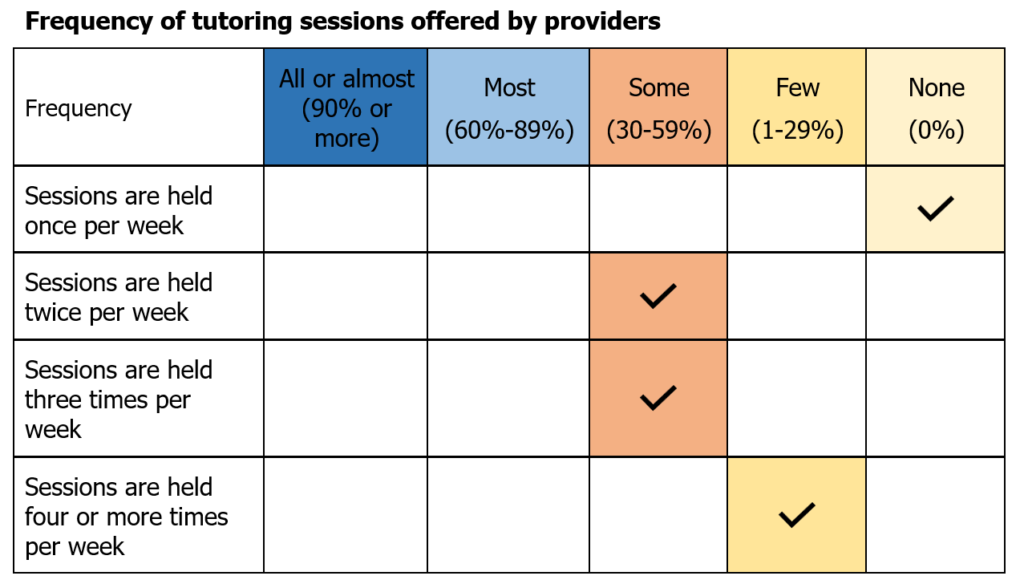

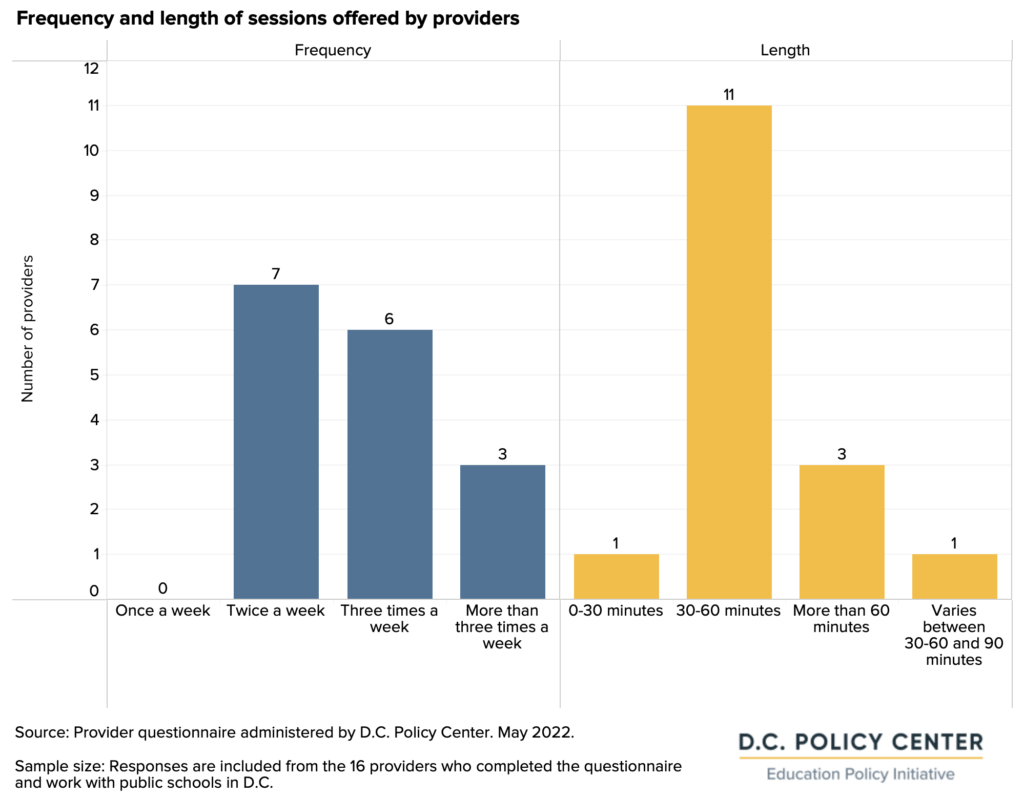

Tutoring is found to be most effective when it occurs three or more times a week for at least 30 minutes, with once a week found to generally not be as effective.[36] All providers offer sessions more than once per week. The most common frequency that sessions were held by providers was twice a week. The next most common frequency was three times a week, followed by more than three times a week. In some cases, working HIT into school schedules three times a week proved difficult, and systems-level actors reported that flexibility was important to implement HIT especially if sessions twice a week allowed students to still receive 90 minutes of weekly tutoring.[37]

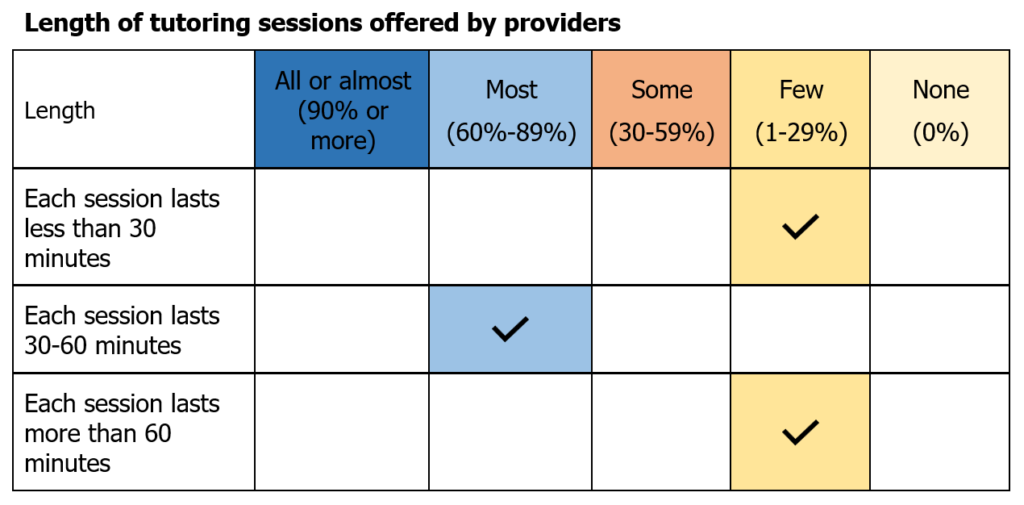

For almost all providers, tutoring sessions last at least 30 minutes. For most providers, sessions last between 30 and 60 minutes. While session frequency and length varied across providers in the design of their programming, for most, students averaged at least 90 minutes of tutoring per week, which is the recommended dosage for most students in OSSE’s definition of HIT.

By subject, providers most commonly focused on early skills of reading and literacy, as well as math, which is aligned with priority subjects in OSSE’s definition. Other reported subjects for HIT included English language arts, science, and social studies. Less than half of responding providers align tutoring with school curriculum. Most providers used a provider-specific curriculum or a nationally recognized curriculum.

Students participating in HIT: Identified by academic performance and attendance metrics

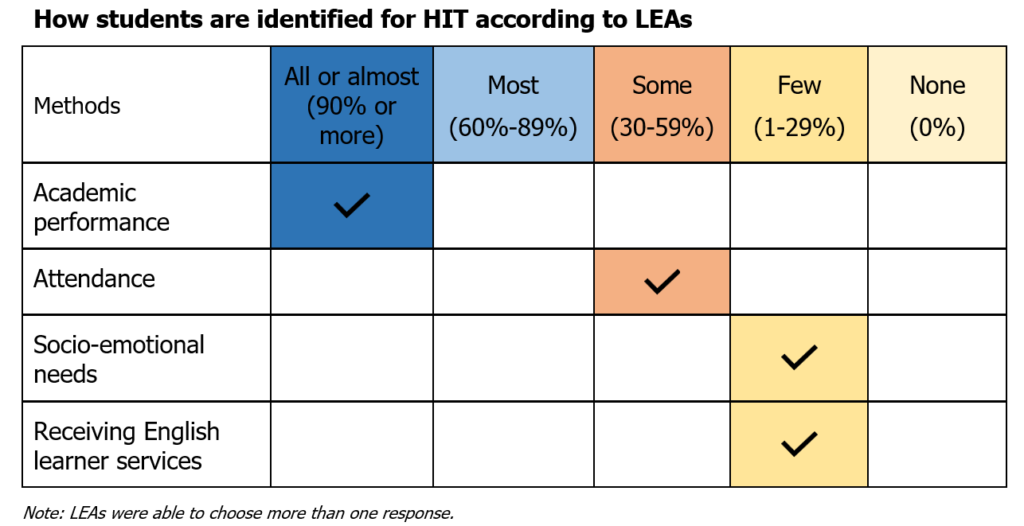

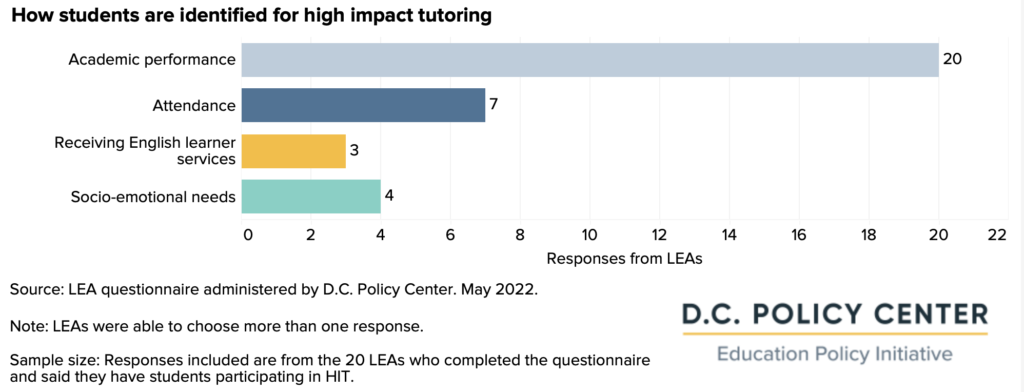

LEAs offered HIT to students across all grade levels at their schools, except for pre-kindergarten. Across all responding LEAs, staff from LEAs or schools—rather than external tutoring providers, or families and students—are responsible for identifying students for HIT. Almost all LEAs identified students for HIT based on their academic performance, which could use a variety of measures around achievement, such as year-to-year academic growth, teacher evaluations, or grades. Some responding LEAs said that attendance was used; and a few LEAs each utilized socio-emotional needs and receiving English learner services to identify students. Half of LEAs use multiple sources of information to identify students for HIT.

Tutors providing HIT: Primarily teachers and college students, and mostly paid

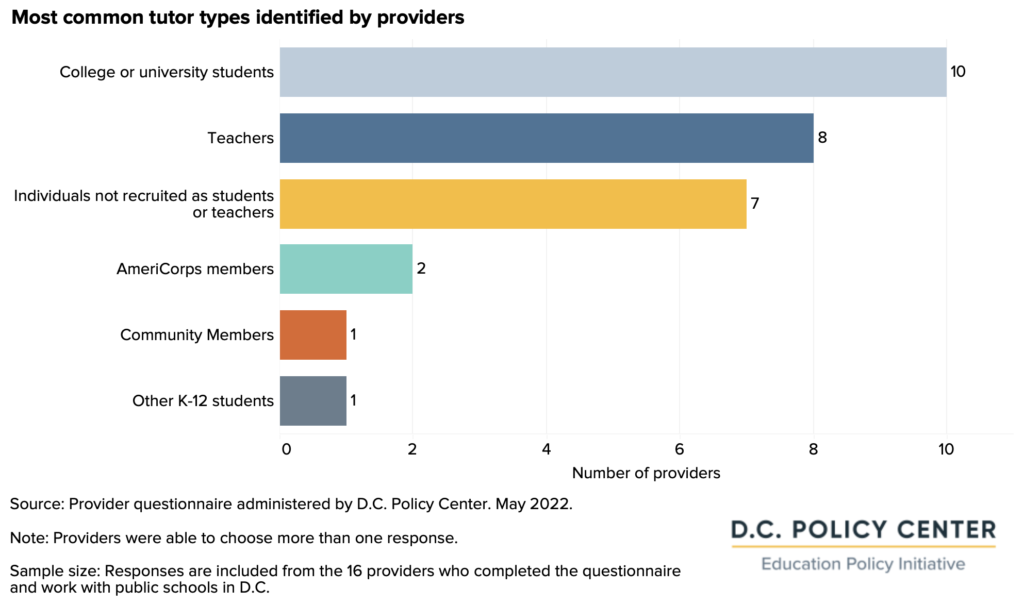

College or university students are the most common type of tutor among providers who responded, followed by teachers and individuals not recruited as students or teachers. Research shows that non-teacher tutors can be effective with sufficient training.[38] Of the providers who partner with schools to provide HIT, more than half worked with college or university students. Many providers worked with teachers and also mentioned working with other individuals such as community members, AmeriCorps service members, or K-12 students to deliver tutoring services. Most providers used a combination of different tutor types.

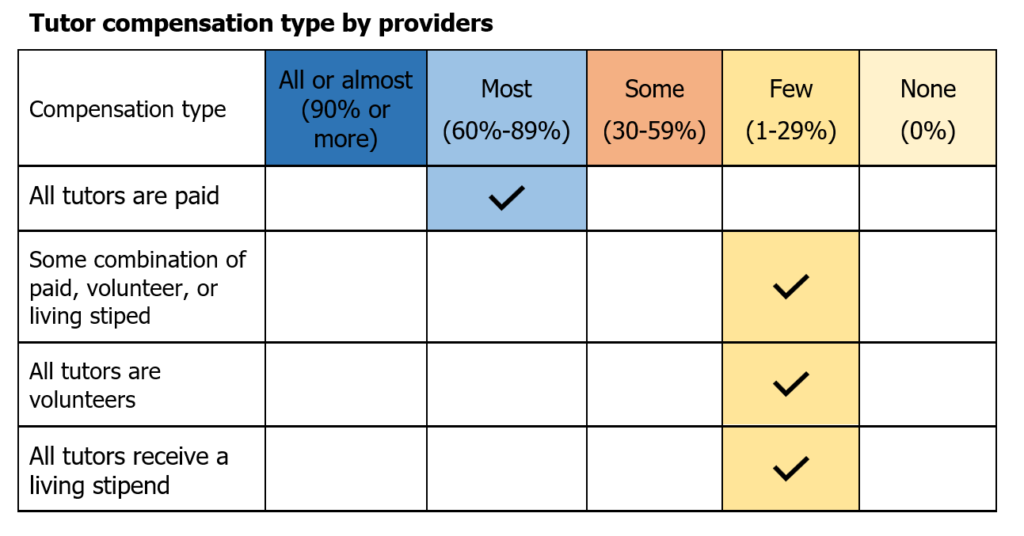

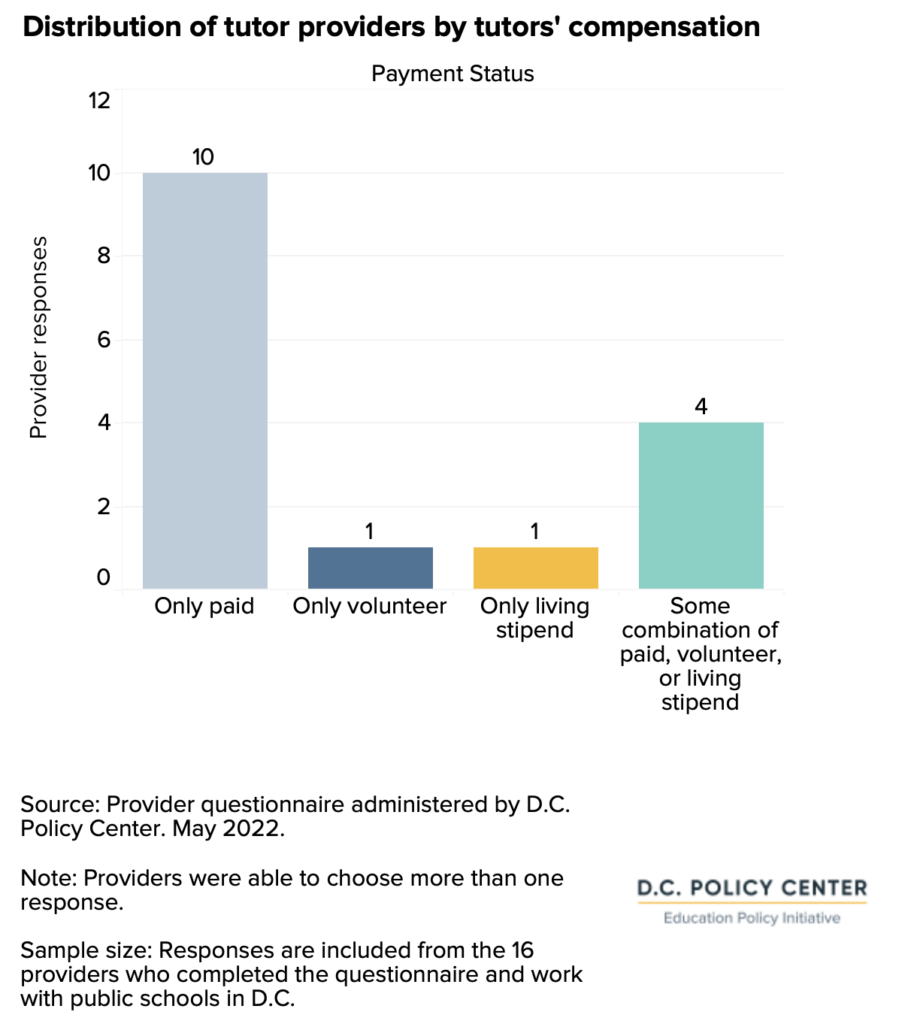

Most tutoring providers paid their tutors. Fewer providers utilized volunteer tutors, and a few providers had tutors who received a living stipend like the one associated with AmeriCorps. Unpaid volunteers have not had as much success with tutoring as those who are paid either in wages or those who donate their services or receive a work-study benefit, although there are exceptions.[39][40]

Spotlight: AU Future Teachers as Tutors

Established in October 2021, American University (AU) Future Teachers as Tutors recruits undergraduate students through the AU School of Education to provide high-impact tutoring services at two of D.C.’s public schools. Sessions are 30-40 minutes in length, and tutors also have an additional built-in 30-minute grace period to complete data input and to allow for flexible student arrivals. In their model, students are pulled out of instructional class time to receive additional support in that area of instruction. For example, students are pulled from English class to receive small group reading support at the same time.

AU Future Teachers as Tutors prioritizes using an established curriculum and providing extensive support to tutors. The program utilizes two curricula: ‘Reading Ready’ for kindergarten and Grade 1 students, and ‘Reading Rescue’ for more advanced readers. Tutors are trained in sessions lasting up to 12 hours in total prior to meeting students. Training includes the curriculum and mock tutoring sessions, in addition to guidance on best practices for entering a school, dress code, and general professionalism. AU also conducts weekly check-ins and ongoing coaching with participating tutors.

Tutors are largely recruited from AU’s School of Education. Tutors are required to participate in 40 hours of tutoring over the course of a semester to receive class credit for their participation. While this pool of tutors may be more motivated to remain engaged because of their career interest, undergraduate tutors sometimes have challenges related to coordinating their own class schedules and having adequate time to commute.

AU Future Teachers as Tutors received support from CityTutor DC during their initial implementation including assistance with transportation issues. The program also received a grant from OSSE to support literacy tutoring.

Source: Interview with AU Future Teachers as Tutors conducted by D.C. Policy Center. August 2022.

LEAs also provided HIT, mostly with their own teaching staff

More than half of the LEAs that responded to the D.C. Policy Center questionnaire reported providing high-impact tutoring through programs that are organized in-house. When LEAs provide HIT with in-house programs, they are responsible for recruiting and training tutors, and organizing sessions, without any help from an external provider. LEA responses show that those who organized tutoring in-house typically used existing teaching and non-teaching staff that had already been hired by the school. Teachers have been identified as the most consistently effective tutors, making this approach a promising one to study.[41]

Some LEAs supplemented their in-house programs with services from an external provider, so it is possible that their students were receiving services from other types of tutors. This variation in how students received tutoring is worth studying, because it can provide insights on making HIT more successful.

Spotlight: Sojourner Truth Public Charter School

Prior to Fall 2021, staff at the Sojourner Truth School, a Montessori school serving students in grades 6 through 8,[42] participated in a Design Sprint with CityTutor DC to implement HIT in their school. They decided on a model that uses dedicated tutors hired and paid directly by the LEA to provide math-focused instruction to students during the school day. Key motivations for the program were being able to find tutors who had prior experience with math tutoring, who could build relationships with students and staff, and who could connect with the school’s mission. During school year 2021-22, the Sojourner Truth School employed between one and three tutors to provide part-time math tutoring—between 5 and 20 hours per week—to students in grades 6 through 8.

Students are selected for participation based on their performance on interim math assessments, as well as conversations with teachers about which students may benefit from additional instruction. Participating students met with tutors during one-hour blocks, scheduled during students’ morning or afternoon 3-hour class block. Because of the Sojourner Truth School’s Montessori model, students were able to coordinate with their teachers and not miss class instruction to attend tutoring. Students meet with tutors one-on-one or in small groups of two, either three times a week on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays or two days a week on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

In addition to their participation in CityTutor’s Design Sprint, administrators at the Sojourner Truth School also participated in coaching as they finalized their tutoring design, held site visits to see tutoring in action, and received general ongoing support. The tutoring program is funded through a combination of philanthropic funding sources and the school’s existing funding.

As the school continues to grow in grades offered and students enrolled, staff would like to sustain current tutoring and expand to more students because of the positive impacts that they have seen. One challenge is ensuring the availability of future funding to hire tutors. Additionally, the school also does not always have adequate space in the building to hold tutoring sessions.

Despite these challenges, staff expressed the many positive impacts of implementing their high-impact tutoring program.

“This was really a win-win-win situation. Kids who received tutoring enjoyed it. They built relationships with tutors. Classroom teachers were happy to see student growth. Overall, it was a really positive experience. In addition to MAP score increases, kids [who participated] were more capable of completing work in class and seemed more confident overall in math class.”

LEA respondent

Source: Interview with The Sojourner Truth School staff conducted by D.C. Policy Center. August 2022.

Preparing tutors for HIT: Tutor training and evaluation plans

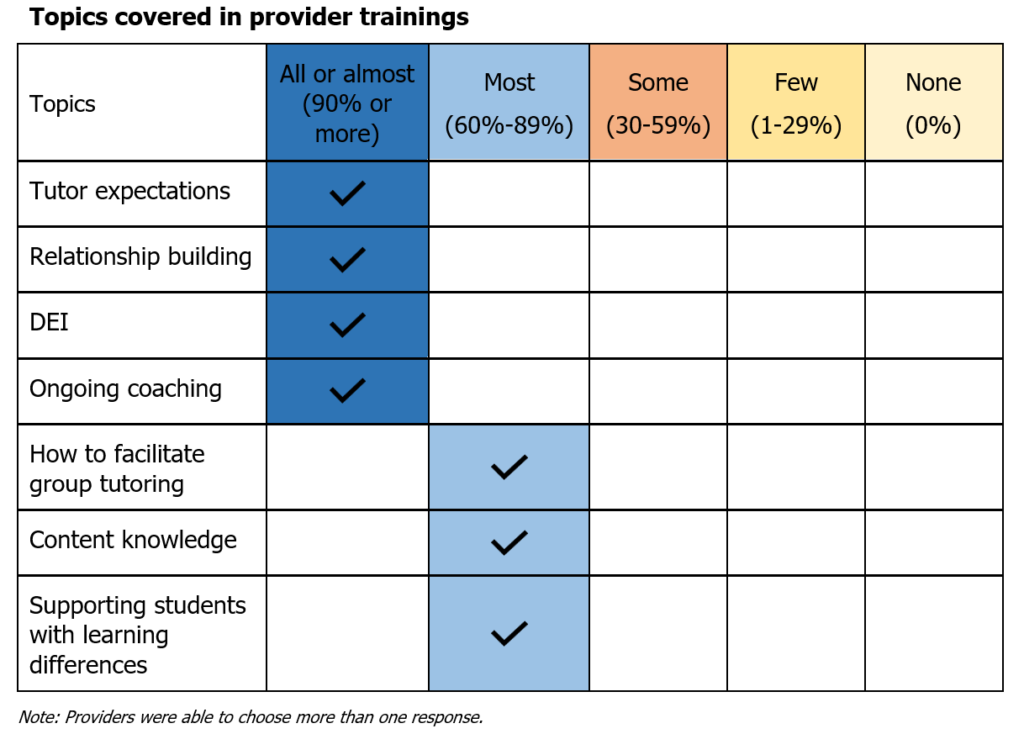

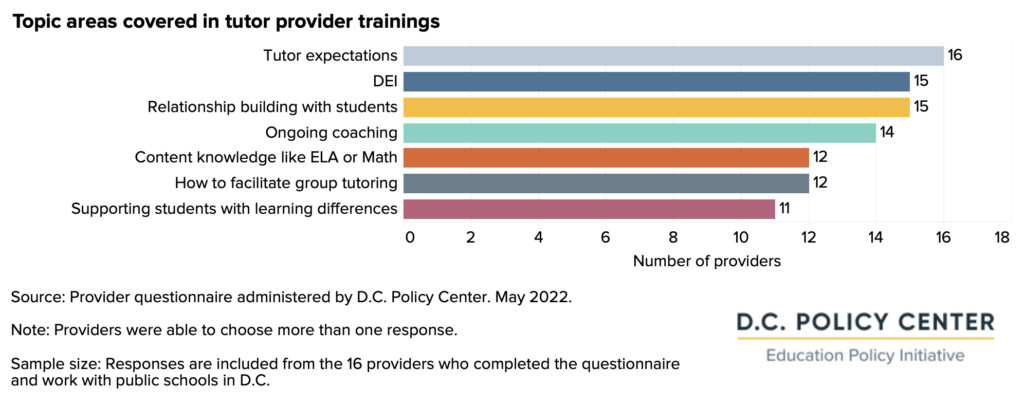

All tutoring providers offered a pre-service training for tutors before the tutors began working with students. This is especially important because most providers indicate generally working with tutors who were not trained as teachers (most teachers who tutor are part of LEA programs). All but one provider also offered an in-service training for tutors after the tutors started working with students. Nearly all providers also offered ongoing coaching for their tutors.

All tutoring providers trained their tutors on professional expectations, including specific school protocols, dress codes, and general professionalism in a school setting. For almost all providers, pre-service training also included topics of diversity, equity, and inclusion and relationship building between the tutor and the student. Trainings also almost always included ongoing coaching. Most providers also incorporated modules on how to facilitate group tutoring sessions, information on content knowledge, and elements of supporting students with learning differences into their training.

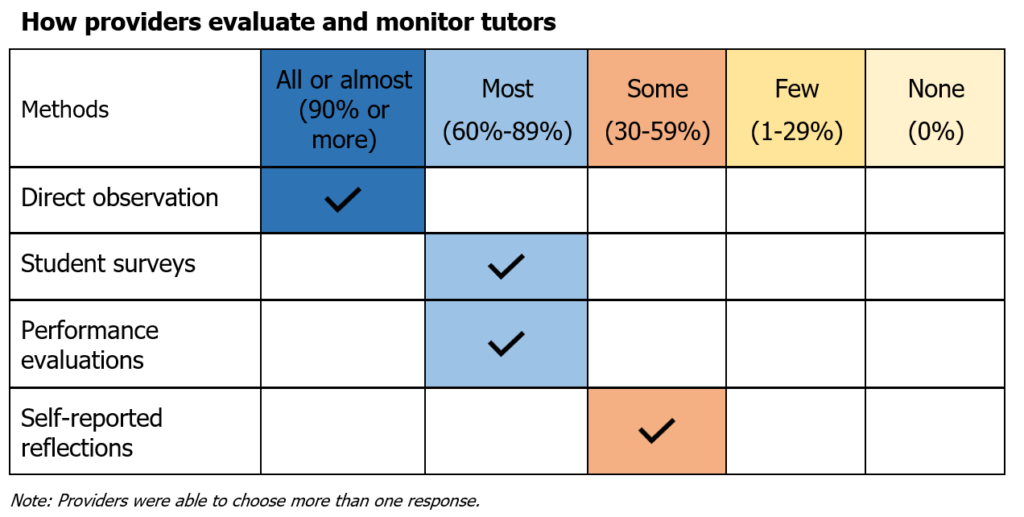

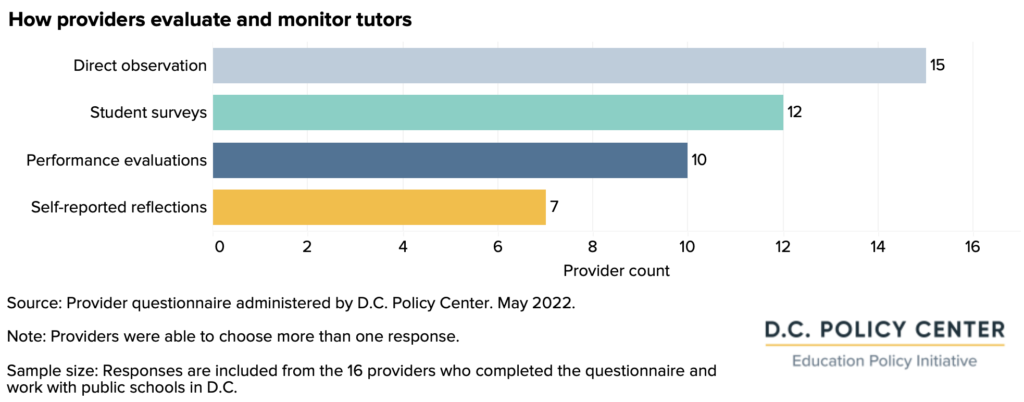

For almost all providers, the most common way to monitor and evaluate tutors was through direct observation. The next most common way was through student surveys, followed by internal performance evaluations, and self-reported reflections.

Reflections on implementation

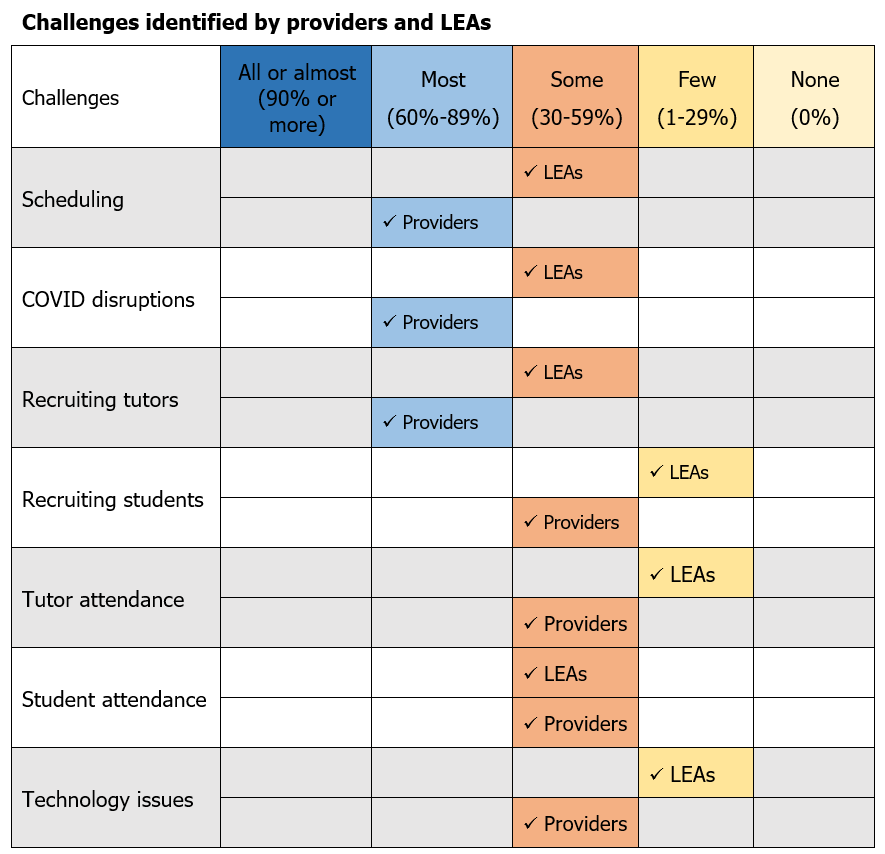

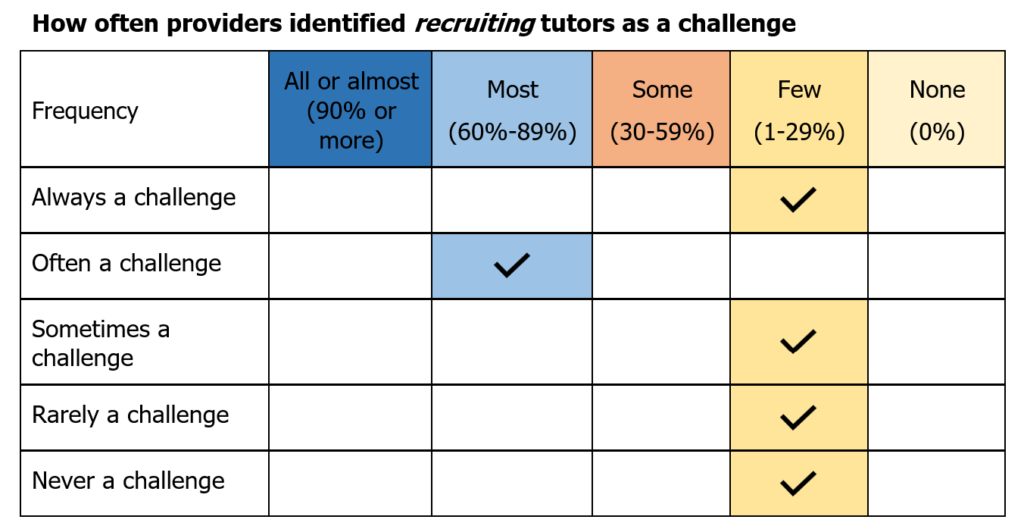

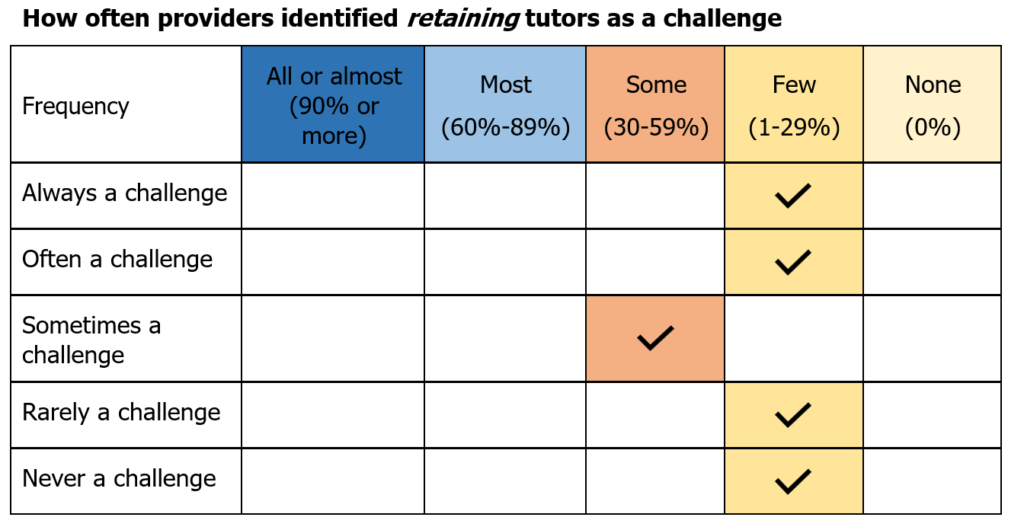

The most-commonly mentioned challenge for providers was COVID disruptions resulting in the last-minute absence of a tutor or participating student. Most providers also struggled with recruiting tutors and scheduling. Some providers mentioned student and tutor attendance and technology issues as challenges.

Unlike the providers who experienced similar challenges, LEAs experienced a myriad of disparate issues. The four biggest challenges LEAs mentioned are scheduling, student attendance, recruiting tutors, and COVID disruptions. Few LEAs also mentioned tutor attendance and recruiting students as well as technology issues as challenges.

Tutor recruitment: A key challenge

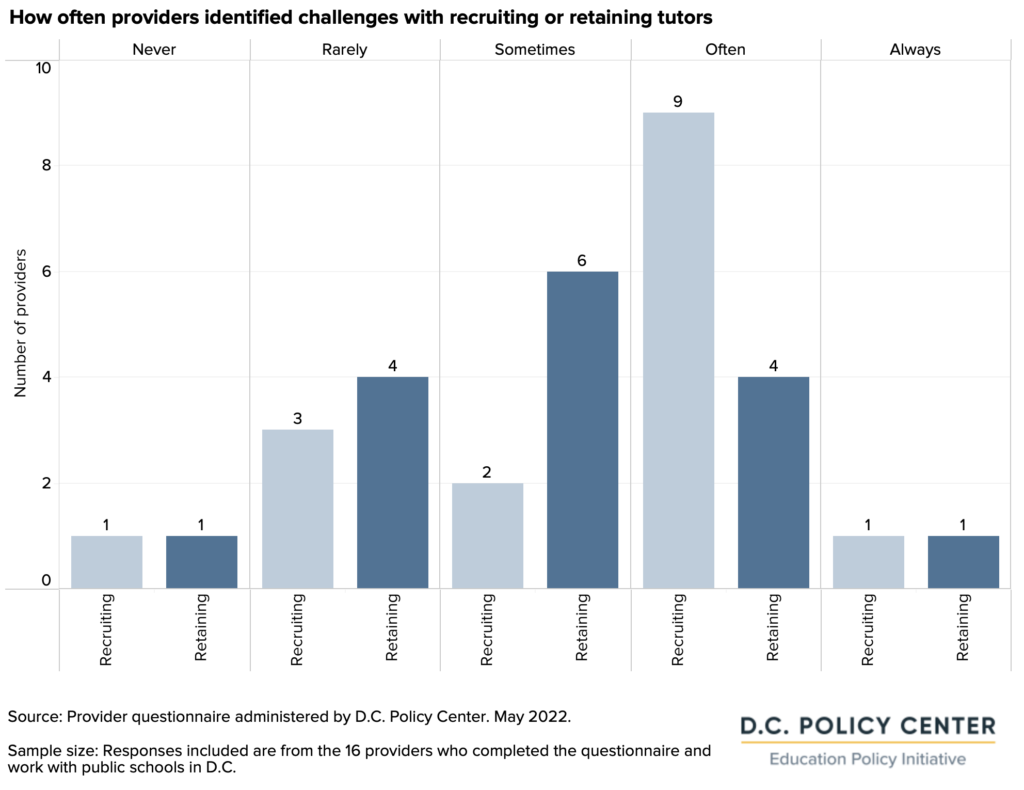

Tutor recruitment and retention are critical to having quality support and for creating strong relationships with students.[43] However, it has been challenging at times to recruit tutors given a relatively tight labor market and smaller labor force than pre-pandemic in D.C.[44] Most providers reported experiencing frequent challenges with recruiting.

A lower share of providers expressed that tutor retention was a challenge. Despite the challenges in recruitment, retention was strong enough to create some stability in who students work with in their tutoring sessions week after week. All providers reported having tutors who work with the same students week to week. More than half the providers reported that tutors often worked with the same student from week to week and the rest of responding providers said that their tutors always do.

“Students eagerly attend tutoring sessions and have developed positive relationships with the tutors.”

LEA respondent

“We are pleased to share that our [tutoring team] members were able to foster strong and productive relationships with students and school partners.”

Tutoring provider

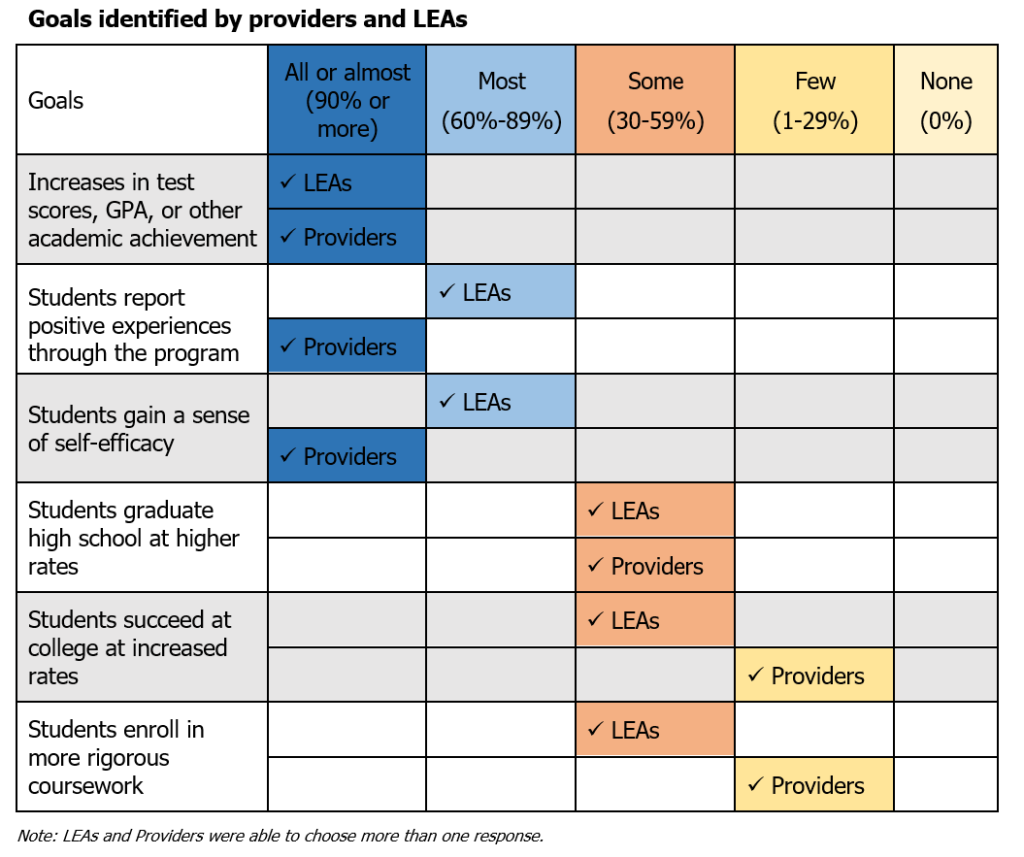

Goals for HIT

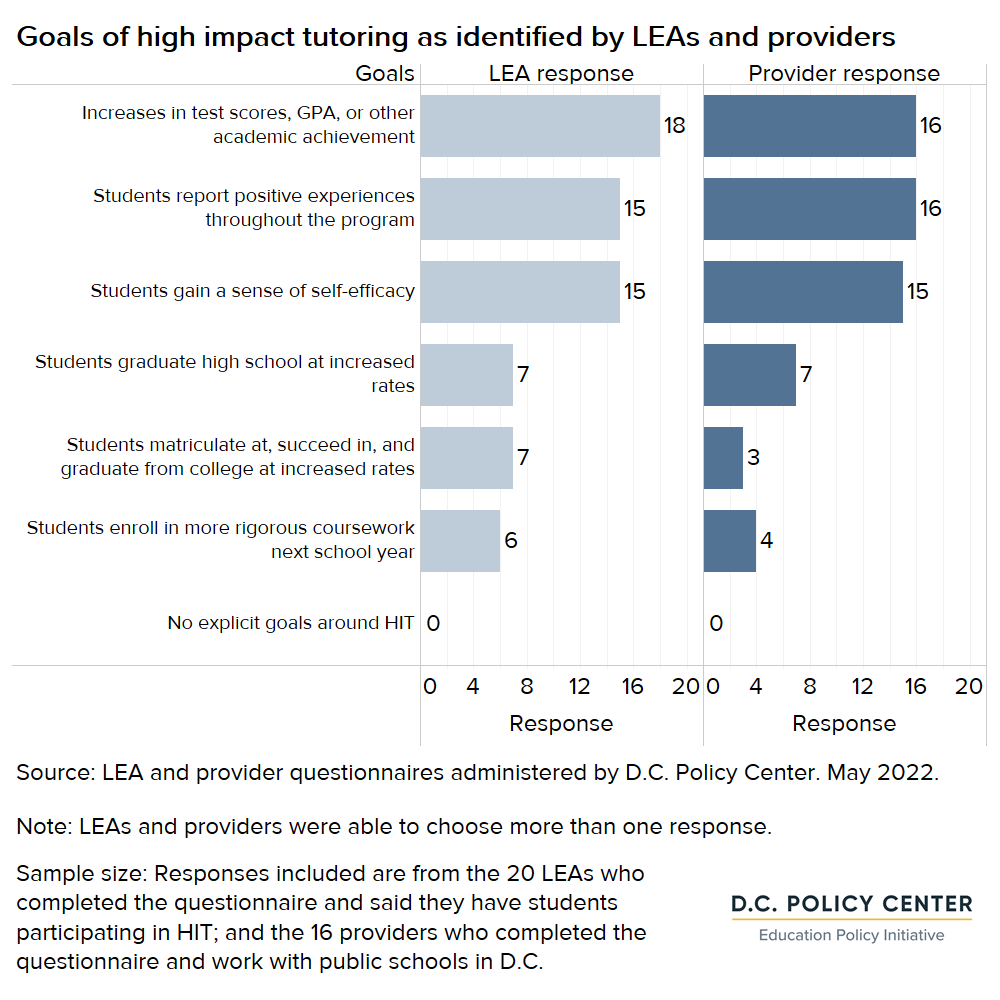

All systems-level actors identified the goal of increasing students’ test scores, GPAs, or academic achievement. Less common was that students report positive experiences with tutoring, or that students gain a sense of self-efficacy. No systems-level actor identified enrolling in more rigorous coursework or improving high school graduation or postsecondary outcomes as explicit goals.

All providers had at least one explicit goal that they hoped to achieve with tutoring. All providers said that their goals included increasing students’ test scores, GPAs or academic achievement as well as students reporting positive experiences throughout the program. All but one provider selected a sense of self-efficacy for students as a goal. Other common goals including more students graduating high school, matriculating in college at increased rates, and enrolling in more rigorous coursework the following school year.

“We administered a family survey this year and families reported how much tutoring has led to student growth in their literacy skills and overall excitement / confidence in school! We are also proud of the impact committed tutors have made with their students returning from a virtual year due to COVID.”

Tutoring provider

Like providers, the most cited goal from LEAs was that students achieve increases in learning as measured by test scores, GPAs, or academic achievement. Fewer hoped for students to achieve positive experiences or that students gain a sense of self-efficacy. Similar to providers, fewer mentioned goals for students graduating high school at higher rates, students matriculating at higher rates, and students enrolling in more rigorous coursework.

“We have seen such an improvement in the students’ outlook on their own achievement. Students who were reluctant to participate our program have opened up and are fully engaging in the instruction being provided.”

LEA respondent

These responses were aligned with systems-level actors, who each prioritized increases in test scores, GPA, or other academic achievement.

“Our teachers are invested in collaborating with tutors to identify the key standard(s) that students need to work on to better access our Tier 1 Math curriculum. Our tutors feel part of the community.”

LEA respondent

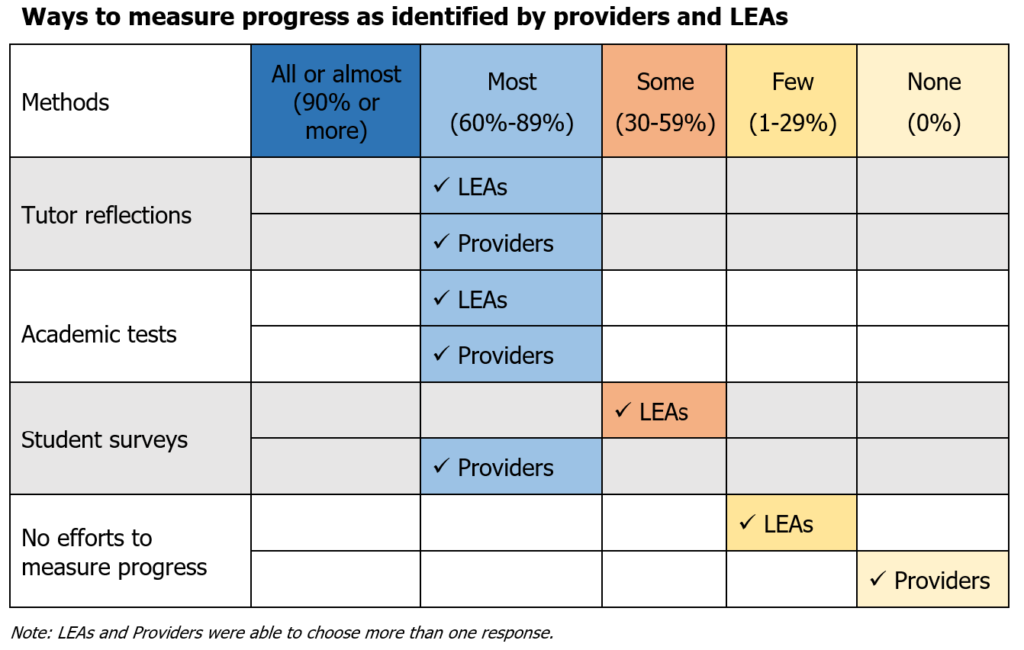

Measuring progress

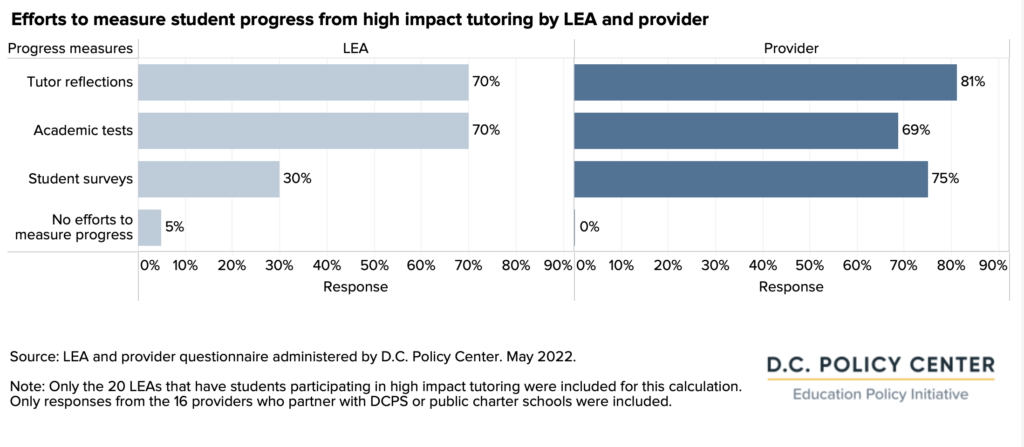

Studies show that using data and informal assessments throughout tutoring programs is an effective way to better adjust tutoring services for students.[45] Providers measure progress most commonly through tutor reflections, student surveys, and academic tests. Individual providers also measure progress through provider-specific databases, third-party assessments,[46] family surveys, or individually developed measures.

Similarly to providers, LEAs also use tutor reflections as one of the most common ways to measure student progress. They also tend to use academic tests. Eight LEAs use skills-based growth measurements. Unlike providers who tend to use student surveys more often, only six LEAs mentioned using this method.

Future plans for HIT, and questions for future research

The first year of HIT implementation in school year 2021-22 required substantive effort and coordination by many stakeholders. Despite the heavy lift, descriptions of common tutor characteristics, sessions, and approaches generally aligned with best practices and definitions for HIT established by D.C., suggesting a collaborative approach was successful to lay the foundation for scalable, citywide HIT. COVID disruptions and tutor recruitment were reported as key challenges to HIT implementation that were heavily influenced by external factors.

While HIT ended up being a common strategy to address disrupted instruction and COVID impacts for a subset of students as an intensive support, there is room to scale up student participation at the school level from this first year of adoption. Moving forward, systems-level actors will continue to evaluate their approaches and expand implementation. They will also begin to research the academic impacts of HIT for D.C. students.

One key decision around HIT is the scale moving forward. From FY22 through FY24, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) will invest $39 million in scaling and supporting HIT across the District, with a particular focus on students designated as at-risk and other students who have experienced disrupted instruction during the pandemic.[47]

In the first round of funding for this initiative in May 2022, OSSE released $20 million to scale HIT, assist with planning and launching tutoring programming, provide strategic program support, and evaluate program services.[48] The selected organizations will collectively serve over 8,000 students during school years 2022-23 and 2023-24 (4,000 in each year) in addition to the 2,200 students reached in school year 2021-22.[49] OSSE also plans to expand the reach of HIT into 90 percent of schools with the most at-risk students by FY24, up from 51 percent of schools with the most at-risk students in FY22.

For FY23, in addition to funding tutoring, OSSE is also launching eight non-school tutoring hubs that will be managed by CityTutor DC, supporting the incubation of new partners, and providing grants to support best practices. OSSE will continue collaborations with CityTutor DC, who was awarded a grant by OSSE to serve as their strategic supports partner through September of 2024, to offer design sprints and boost implementation and capacity building efforts.

In school year 2022-23, CityTutor DC plans to continue their primary strategies to strengthen the tutor force, build LEA capacity to implement HIT, support out-of-school HIT at CityTutor Hubs, and create a strong network of stakeholders for continuous growth. One major shift in CityTutor DC’s approach will mean federal funds go directly to tutoring providers in school year 2022-23, rather than from philanthropic funds that supported CityTutor’s investment efforts in 2021-22. This shift will pivot CityTutor DC’s focus on improving the foundation of HIT from school year 2021-22. CityTutor DC will continue to provide strategic support for schools and citywide tutoring efforts in design, implementation, training, as well as an additional investment in new tutoring providers and community-based tutoring hubs with a goal of serving 4,000 students in school year 2022-23.

At the LEA level, LEAs serving 88 percent of students in pre-kindergarten through grade 12 report that they plan to implement HIT in Continuous Education Plans for school year 2022-23.[50]

There is some overlap in the students who will be served by OSSE-funded and CityTutor DC-supported programs, as well as LEA efforts, so these targets for program reach cannot be added together to estimate a citywide goal.

Future research

Figuring out what works in tutoring for D.C.’s students will be critical to evaluating efforts and adjusting approaches in the years to come as recovery from the pandemic continues. Both OSSE and CityTutor DC have plans to inform continuous improvement and evaluate the efficacy of HIT efforts over time. LEAs and providers also shared a few additional ideas for future research when responding to the questionnaire.

OSSE will work with the National Student Support Accelerator of the Annenberg Institute at Brown University, who will conduct a long-term evaluation that will explore the effect of HIT on student academic achievement for students receiving tutoring from OSSE grantees from FY22 through FY24. The study will incorporate quantitative and qualitative data from surveys and interviews conducted with tutoring providers, tutors, students, and school staff.[51] Their work will support continuous improvement as well as a summative evaluation. The study methodology will be finalized and research activities will begin in fall of 2022.

CityTutor DC’s HIT efforts in school year 2021-22 will be highlighted in a CityBridge white paper in fall of 2022 with analysis by EmpowerK12. CityTutor DC collected data last school year for continuous growth purposes and to identify support needs and exemplary bright spots. CityTutor DC’s HIT efforts in 2022-23, funded by OSSE, will also be evaluated by the National Student Support Accelerator of the Annenberg Institute at Brown University as part of OSSE’s research.

In the D.C. Policy Center questionnaire, LEAs shared a demand for more research on the effectiveness of HIT, which programs or curriculums see the most impact, and how the gains seen from HIT carry over from year to year. One provider described a need for a study of program element effectiveness, while two others described needing more research on the importance of making sure pedagogy is culturally relevant and how student outcomes are related to family engagement.

While federal funds are available for HIT through FY24, D.C. will need to use the next few years to answer questions about HIT’s scale and intended impact. D.C. will need to decide which students should be the intended participants in HIT. With whom has it been most effective to date? How can HIT, a complex and resource-intensive intervention, be implemented with fidelity? How can D.C. enable the long-term sustainability of HIT? Answering these questions through future evaluations or research will allow D.C. schools to tighten HIT approaches with more knowledge on what works and lessons learned.

Appendix A: Overview of D.C. Policy Center HIT questionnaire

In May and June of 2022, the D.C. Policy Center circulated a questionnaire to systems-level actors, LEAs, and tutoring providers in D.C. to find out more about HIT during school year 2021-22. Details on responses from LEAs and providers are included below.

Systems-level responses

D.C. Policy Center distributed a questionnaire to three agencies and organizations that are central to high-impact tutoring in D.C.—the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE), the Office of Out of School Time Grants and Youth Outcomes (OST Office) in the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education (DME), and CityTutor D.C. All three agencies provided funding directly to tutoring providers in school year 2021-22, in addition to providing capacity and coordination support to LEAs and providers. While distinct entities, the three agencies engage in a high degree of collaboration and communication in their efforts to scale high-impact tutoring in D.C.

LEA responses

Twenty-six out of 60 LEAs responded to the questionnaire on high-impact tutoring, representing 80 percent of students enrolled in D.C.’s public schools. Of those who responded, 20 LEAs, which represent approximately 76 percent of students enrolled, responded that they have students participating in high-impact tutoring. Eleven LEAs provide HIT directly (using their own staff); of these, five LEAs also work with an external provider. Nine LEAs do not have any staff providing HIT directly and instead work with an external provider. The discussion on LEA-provided tutoring draws from the responses received from these eleven LEAs.

DCPS school responses

D.C. Policy Center distributed the questionnaire to all DCPS schools via DCPS central office and followed up with individual outreach to principals. Responses were received from 19 schools representing 17 percent of students enrolled in DCPS. Responses from individual schools are not included in LEA-level analysis but are used to provide context throughout the report.

Provider responses

Through desk research[52] and information provided by OSSE and CityTutor DC., the D.C. Policy Center identified 30 active tutoring providers in D.C. and distributed the questionnaire to these entities. Eighteen tutoring providers completed the questionnaire. Of the 18, 16 reported partnering with DCPS or public charter schools to provide HIT during school year 2021-22. Only responses from these 16 providers are included in this report’s analysis. Overall, providers partnered with 119 out of 224 PK-12 schools in D.C., including both DCPS and public charter schools.

The 16 provider respondents likely include the main providers of tutoring in D.C. To estimate the reach of providers, the D.C. Policy Center categorized providers into four groups based on the strength of their established connections over time with schools, number of schools served, as well as whether services provided are primarily software-based. In the group with the largest reach in D.C., both providers responded to the questionnaire. Six of nine providers who are established in D.C. and serving multiple schools responded. Of the providers in the third group who are smaller and do not consistently publish their number of tutors or number of students serve, five of eight providers responded. Out of the fourth group of providers that are mostly virtual or software-based and publish no information about their partnerships online, five of 11 providers responded.

Throughout the report, findings are qualitative in nature and described on a scale based on the frequency of each response option. For many questions, respondents were able to choose only one response. It is noted for each question where respondents were able to choose more than one response for their answer. The same scale applies to both types of questions. Note that these scales refer to the number of respondents per question and do not describe the providers’ reach or LEA’s size. Responses are self-reported and do not measure implementation.

Appendix B: Summary of responses to provider and LEA questionnaires

Scale of tutoring as described by providers

Implementation of HIT

HIT sessions

Students participating in HIT

Tutors providing HIT

Preparing tutors for HIT

Reflections on implementation