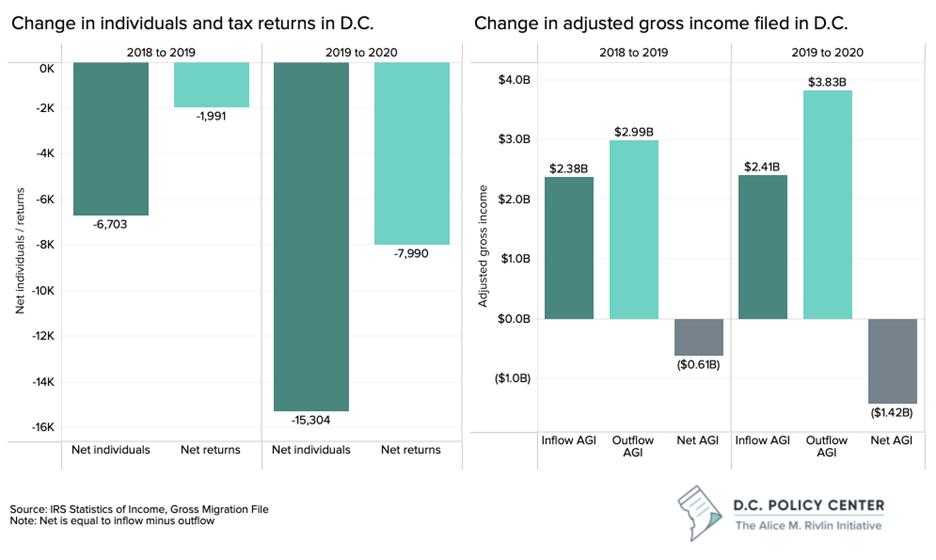

According to the Internal Revenue Service’s migration data, D.C. lost 15,304 residents and 7,990 tax filers between 2019 and 2020. Pre-pandemic, between 2018 and 2019, D.C. also lost residents and filers, but in the first year of the pandemic, these losses increased greatly. Importantly, 60 percent of the leavers were tax filing units (individuals, couples, or families) that had taxable incomes of $100,000 or more. These are clearly filers with jobs.

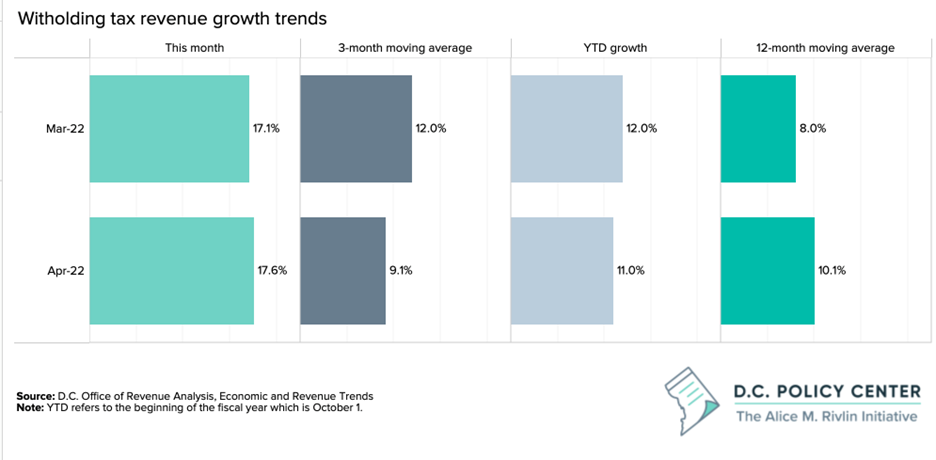

At the same time, the withholding portion of income tax collections–the income taxes that are directly taken out of paychecks every pay period–is growing at 10 to 11 percent.1 That means that the wage and salary incomes of District residents are growing despite this loss.

How could we be losing high-income taxpayers and still experiencing such strong growth in withholding? This is an important question, and its answer has definitive implications of the resiliency of the District’s tax regime.

Who is leaving, by income?

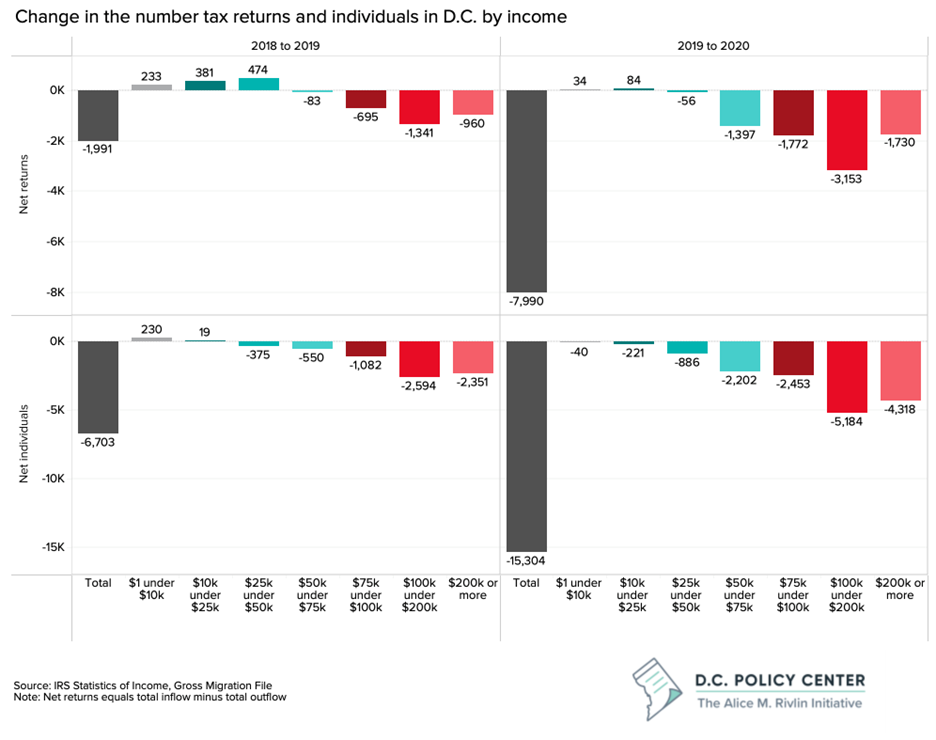

The IRS data show that the bulk of net outflow is concentrated in individuals and households with taxable incomes above $100,000: 61 percent of net tax filers who moved out of the city between 2019 and 2020 had incomes greater than $100,000. They were also the largest group who moved out of the city pre-pandemic.

The data also show that leavers are increasingly including lower-income households. Last year, the city still experienced a net inflow of tax filers earning under $50,000. In 2020, the District had very little net inflow of filers in any income bracket, and out-migration has spread to low- and middle-income brackets.

Who is leaving, by age?

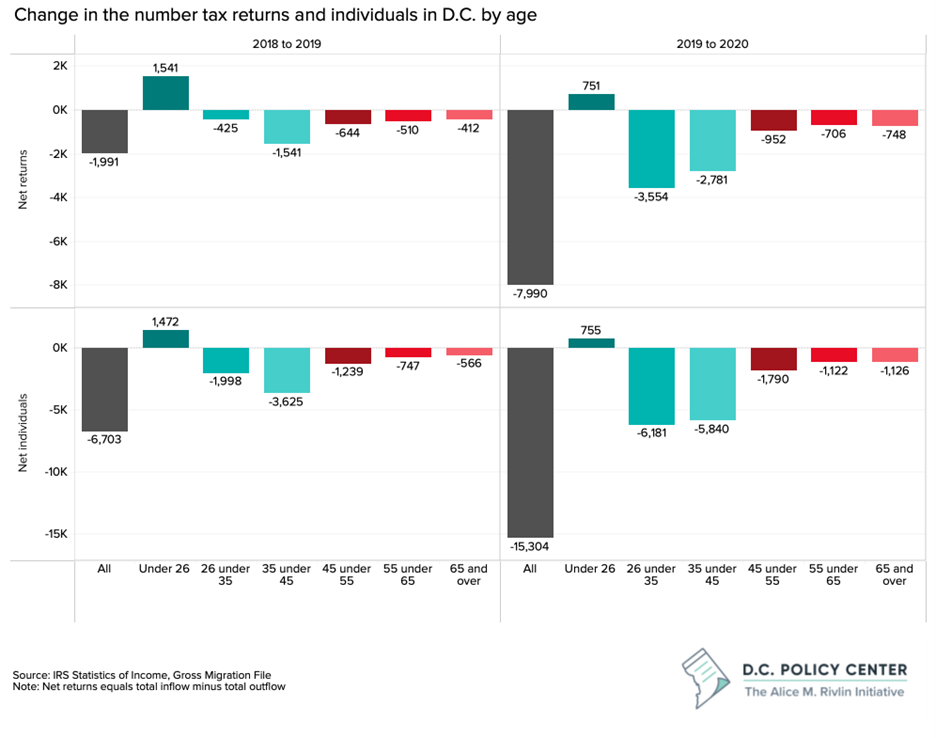

By age, the District is primarily losing tax filers and residents aged 26 to 45. This group accounted for nearly 80 percent of net loss in tax filers between 2019 and 2020. This trend echoes what was happening before the pandemic, but at an increased scale. Residents and tax filers in this age group are particularly important to the District because of their income growth potential and because they are in the age group most likely to start families in the city. Under 26 is the only age group with a net inflow of filers in 2020; however, looking deeper into the data, the majority of filers in this group earn less than $10,000 annually, implying that they are largely students.

How does this impact the tax base?

Between 2019 and 2020, the net loss of filers led to a net loss of $1.42 billion in income reported to the IRS. And, income lost due to net out-migration increased by $814 million compared to the losses between 2018 and 2019. If every filer was on the lowest end of the city’s income tax rate brackets, which we know is not the case, this equates to a loss of $57 million in income tax revenue. On the other end of the spectrum, if every filer were on the highest end of the city’s income tax rate brackets, which more closely aligns with reality, it would equate to approximately $153 million lost in income tax revenue. The increasing outflow of income, and thus, revenue, is primarily coming from wealthier households and those aged 26 to 45.

Why, then, are withholding taxes increasing?

While net outmigration numbers increased, they still remain a relatively small share of the total tax filers. Thus, withholding taxes could be increasing if the city is increasingly occupied by high-wage earners, who can afford the high costs of housing and child care, among other things. In fact, we had observed in the past that taxable income has been growing much faster than tax filing units, and post-pandemic, high-wage jobs have been replacing low-wage jobs. This may sound like great news, but in some ways it is not. First, lack of income diversity in the city can change the direction of policy (and politics). Second, the District worked hard to bring families and middle-income households back to the city after the Revitalization Act, and the IRS data show us that this trend might be reversing.

Are IRS data giving us the full picture?

These numbers—a loss of 15,304 residents—are different from the U.S. Census domestic outmigration estimate for the period of July 1, 2020 and June 20, 2021. That data showed the District lost 23,000 residents to net domestic outmigration. These differences certainly can emanate from methodology differences as well as timing differences. But they also suggest that there could be another shoe to drop if some D.C. residents who moved elsewhere during that period intended their move to be temporary, and therefore kept D.C. as their domicile and continued withholding taxes in D.C. If these residents return, income tax collections would not be impacted, but economic activity could increase. But if they decided to stay where they are currently, there might be another hit to the District’s tax base.

Endnotes

- Information obtained from the Office of the Chief Financial Officer shows that year to date (beginning October 2021, the beginning of the fiscal year) withholding tax revenue grew by 11 percent compared to the same period last year, and three month moving average as of April 2022, was 9.9 percent higher than the same metric from a year ago. The March 2022 values for the same metric show similarly strong growth and can be found here, on page 16.