In an essay on tax practices that amplify racial inequities, D.C. Policy Center Executive Director Yesim Sayin Taylor examines how property tax treatment of owner-occupied housing amplifies existing inequalities in wealth, both today and in generations to come. However, the landscape for today’s racial disparities in income, wealth, and home ownership, as well as the patterns of segregation and underinvestment, follow from a long history of public and private practices that have discriminated against Black communities and other communities of color.

Many experts have explored how racial disparities in the present day have stemmed from policies and practices in the District’s history. The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital—a joint publication of the Urban Institute, Duke University, The New School, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development—is one such vital resource, tracing the barriers that prevented D.C.’s Black residents from building wealth and assets from the Black Codes of the 1840s through the destruction of the Barry Farms community in the 1940s, as well as white flight, urban renewal, and the effects of the Greatc Recession. Along with books like Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Howard Gillette, Jr.’s Between Justice & Beauty: Race, Planning, and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, D.C., and Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove’s Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital, The Color of Wealth shows that D.C.’s Black residents were not passively priced out of housing in high-opportunity areas due to the legacy effects of slavery; they were explicitly discouraged and barred from renting or purchasing homes by the federal government, banks, realtors, and citizens associations.[1]

This supplementary publication gives a brief summary of this history in the 20th century through today in order to provide context for discussions of present-day practices, drawing on these and other resources. It is part of a broader series of essays about racial equity in D.C., including a written symposium on achieving racial equity in housing outcomes, available at dcpolicycenter.org/racialequity.

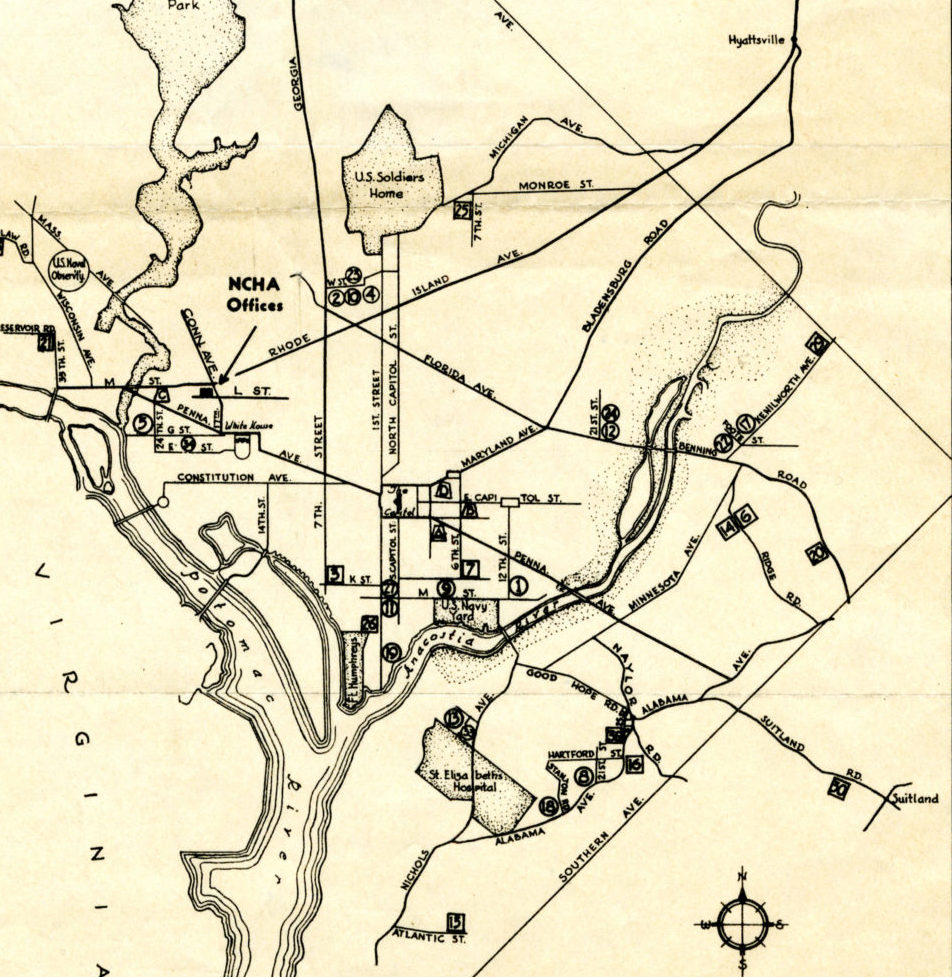

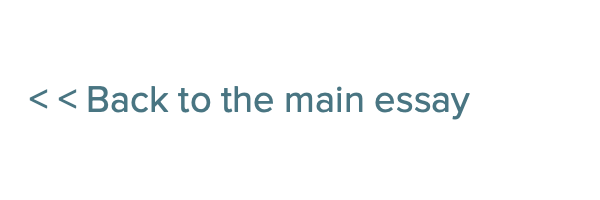

Map of D.C. Public housing projects by race, 1944. U.S. Government Printing Office. Source: DC Public Library, Special Collections, Washingtoniana Map Collection. Cited by Prologue DC in Mapping Segregation: How Racially Restricted Housing Shaped Ward 4.

Redlining, white flight, and urban renewal in Washington, D.C.

As Richard Rothstein documents in The Color of Law, government regulations and recommendations at every level of government sought to keep Black and white residents separated, subsidizing construction, loans, and housing for white residents while preventing Black residents from building wealth through homeownership.[2]

Across the country, federal housing policies drew white families from the cities to create segregated suburbs,[3] building white wealth and while hollowing out the tax base of American cities. In response to these new affordable housing opportunities and their resistance to the integration of public schools and other public and private urban spaces,[4] among other factors, almost 60 percent of the District’s white population left the city in a 20-year span, falling from 517,000 residents in 1950 to 209,000 in 1970. (For a more granular exploration of these dynamics and their effects at the neighborhood level, see Prologue DC’s interactive feature How Racially Restricted Housing Shaped Ward 4.)

At the same time, because Black residents were prohibited from living in many neighborhoods, the public and private housing options where they could live often became overcrowded, and eventually deteriorated in quality. As a result of this neglect and intentional underinvestment, Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove write in Chocolate City, in 1960, “more than 12 percent of black homes in the city lacked running water; more than 16 percent lacked electricity.”[5] Cities also placed industrial sites, landfills, and even toxic waste sites in Black neighborhoods, which both harmed the residents and “contributed to giving African Americans the image of slum dwellers in the eyes of whites who lived in neighborhoods where integration might be a possibility.”[6]

Officials only addressed low-income Black residents’ poor living conditions through the extreme measures of urban renewal, in which thousands of homes were demolished in order to attract higher-income residents. As Howard Gillette, Jr. writes in Between Justice & Beauty, D.C. razed almost all of the buildings in the southwest quadrant, but did not replace housing for low-income residents; in fact, “of the 5,900 new units constructed, only 310 could be classified as moderate-income.”[7] The displacement of low-income Black residents destabilized communities and disrupted families.[8],[9]

Meanwhile, many middle-class Black families left the city in the 1970s, pushed by the aftermath of the 1968 riots and pulled by new suburban housing opportunities opened up by the Fair Housing Act. But by that time, many of the suburban homes that the federal government had subsidized were no longer affordable; this window of opportunity for economic mobility had closed.

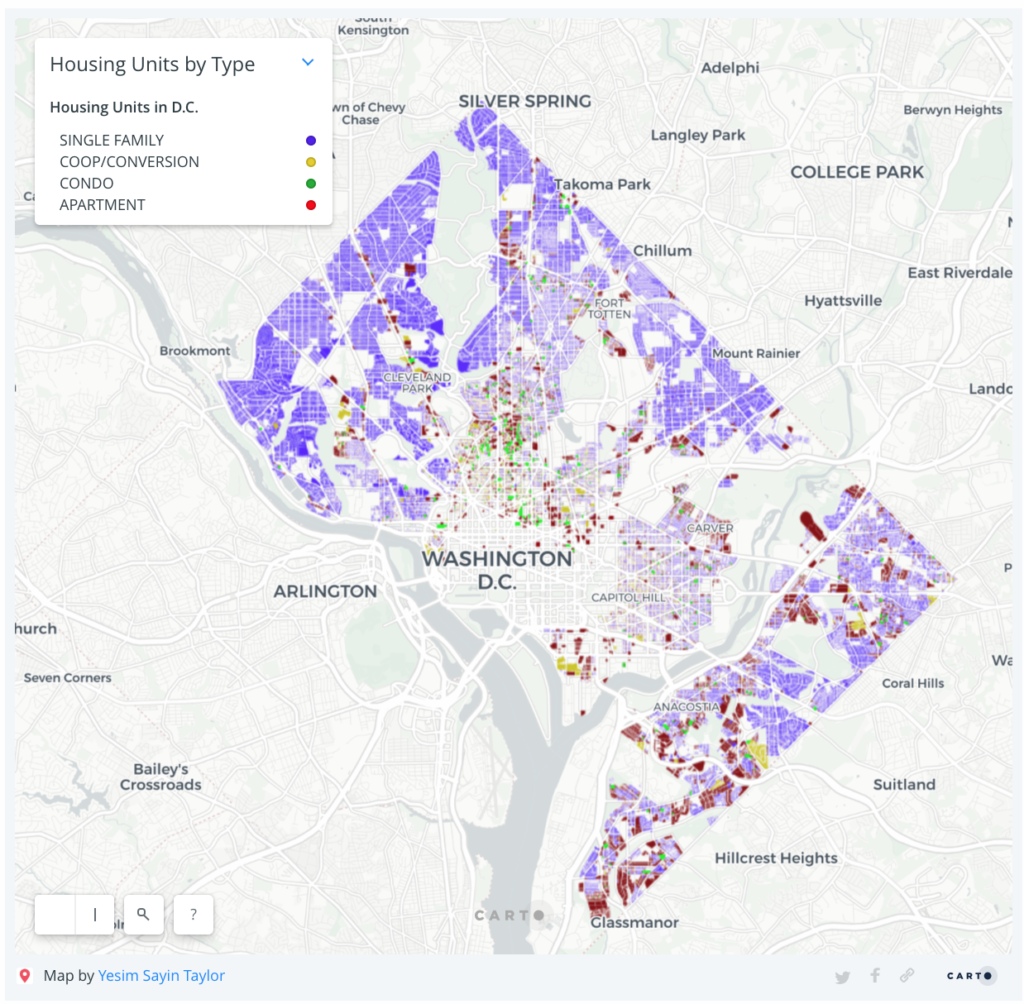

In the parts of cities where white residents remained, many jurisdictions used zoning and other tools to keep certain neighborhoods comprised of low-density, single-family homes, while concentrating apartment buildings in low-income areas of town. In D.C., almost the entirety of Ward 3’s land zoned for residential use is occupied by single-family units, while multifamily units occupy a majority of the residential land in Ward 8. Nationally, Rothstein writes that while decisions to zone middle-class neighborhoods for single-family homes were strongly motivated by class-based elitism, “there was also enough open racial intent behind exclusionary zoning that it is integral to the story of de jure segregation.”[10]

Types of housing in D.C. Source: Taking Stock of the District’s Housing Stock: Capacity, Affordability, and Pressures on Family Housing (2018)

These exclusionary and segregationist housing policies from the early- and mid-20th century had clear effects for later generations. One effect has been through the intergenerational transfer of housing wealth, as home equity allowed white residents to build economically stable lives and send their children to college, as Rothstein and others have noted. Another effect has been to establish residential patterns of segregation and disinvestment, which place an additional burden on families of color, beyond income: Today, middle- and high-income Black families are far more likely to live in low-income neighborhoods than white families with similar income levels, and Black Americans continue to experience lower rates of upward economic mobility than white Americans. These barriers are particularly acute for Black men; economist Raj Chetty and his co-authors found that, “controlling for parental income, Black boys have lower incomes in adulthood than white boys in 99% of Census tracts.”

The 2008 financial crisis and beyond

In the years before the 2008 financial crisis, predatory banks and mortgage lenders approved Black and Latinx applicants with poor credit for subprime loans, leaving them with high interest rates even as the housing market collapsed. Even Black and Latinx applicants with good credit were more likely to be denied traditional loans and steered towards subprime loans instead.[11] According to the Urban Institute, “despite holding less wealth overall, Black households also hold a larger share of their wealth in homeownership than white households (48.6 percent vs. 27.7 percent of total wealth), which hurt them more severely during the housing crisis.”

Now that credit has tightened once again, Black and Hispanic families are most likely to miss out on homeownership. Recent research from Zillow shows that the gap between white homeownership and Black homeownership was greater in 2016 than it was in 1900.[12] While much of this disparity appears to be tied to differences in credit scores post-recession, other research suggests that redlining is not purely an artifact of the past. An investigation by Reveal found that African Americans, Latinxs, Asians, and Native Americans are still more likely to be denied a conventional mortgage loan than white applicants in dozens of U.S. metropolitan areas (including the D.C. metro area), even after controlling for the applicants’ income, loan amount, and certain neighborhood characteristics.

Kathryn Zickuhr is the Deputy Director of Policy for the D.C. Policy Center.

Notes

[1] Local historians at Prologue DC have mapped many of the racially restrictive covenants and other agreements put in place by white homeowners and realtors in D.C., especially in Ward 4.

[2] The Federal Housing Administration manual for underwriting loans explicitly stated that “incompatible racial groups should not be permitted to live in the same communities,” and that loans to black borrowers could not be insured. It even recommended using highways to separate white neighborhoods and black neighborhoods.

[3] As documented by The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital, the community of Greenbelt in Prince George’s County was one of these white-only suburbs whose population jumped in the 1960s and 1970s. (The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital, page 22. For more, see Tom Lewis, Washington: A History of Our National City.) The city now has a population that is 63 percent Black, 16 percent Hispanic, and 14 percent white; in much of the rest of the county, most census block groups are over 80 percent black.

[4] These dynamics continue today.

[5] Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital, page 291.

[6] Rothstein, page 56.

[7] Between Justice and Beauty, page 163.

[8] Ibid., page 165.

[9] Another instance, as shown in The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital, black residents in D.C. had created a thriving community in Barry Farms immediately following the Civil War. However, “individual and community assets in Barry Farms were destroyed to accommodate government urban renewal and infrastructure decisions” during the Great Depression and World War II. See The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital, page 21.

[10] Rothstein, page 48.

[11] According to sociologist Jacob W. Faber, “Income was positively associated with receipt of subprime loans for minorities, whereas the opposite was true for whites. When expensive (jumbo) loans were excluded from the sample, regressions found an even stronger, positive association between income and subprime likelihood for minorities, supporting the theory that wealthier minorities were targeted for subprime loans when they could have qualified for prime loans.”

[12] In 1900, 48.1 percent of white households in the United States owned homes, while only 20.5 percent of black households did–for a homeownership gap of 27.6 percentage points. The gap is 30.3 percentage points, according to 2016 U.S. Census Bureau data.

Main sources and further reading

Kilolo Kijakazi et al, The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital. A joint publication of the Urban Institute, Duke University, The New School, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development. November 2016.

Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. 2017.

Thomas M. Shapiro and Melvin L. Oliver. Black Wealth/ White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality. 1995.

Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove, Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital. 2017.

Howard Gillette, Jr., Between Justice & Beauty: Race, Planning, and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, D.C. 1995.

Prologue DC, Mapping Segregation in Washington, DC: How Racially Restricted Housing Shaped Ward 4. Updated 2018.

Last updated October 2018.

Feature photo: Map of D.C. Public housing projects by race, 1944. U.S. Government Printing Office. Source: DC Public Library, Special Collections, Washingtoniana Map Collection. Cited by Prologue DC in Mapping Segregation: How Racially Restricted Housing Shaped Ward 4.