On Tuesday, November 1, 2022, Executive Director Yesim Sayin testified at a public roundtable hosted by the D.C. Office of Planning on the future of housing in downtown areas. She discussed:

- Why housing production is even more critical today than it has ever been for the city’s continued vibrancy,

- Some of the promising ways to increase the production of housing in downtown areas (specifically those areas within the D Zone overlay), and

- Why the Office of the Attorney General’s proposal to expand Inclusionary Zoning requirements into D Zones will impede, and not support, the goal of increasing housing, especially affordable housing in D Zones.

You can read her testimony below, or download a PDF copy.

Housing production is more critical today than it has ever been.

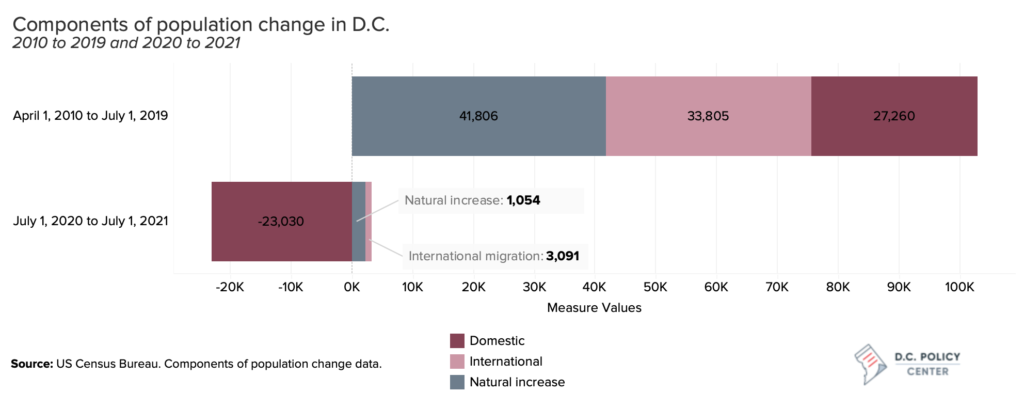

As remote work has taken hold, it has been breaking the relationship between where people live and where they work. This trend has had two distinct but connected effects on the city: first, the loss of population, largely driven by outmigration, and second, the loss of commuter activity.

In 2021 alone, the District lost 23,000 residents to net out-migration, reversing 85 percent of the population growth that was driven by in-migration in the previous decade. Much of this decline can be attributed to remote work, as it reflects the national trends that show many high-cost employment centers around the country similarly lost population to lower-cost, smaller metropolitan areas. 1

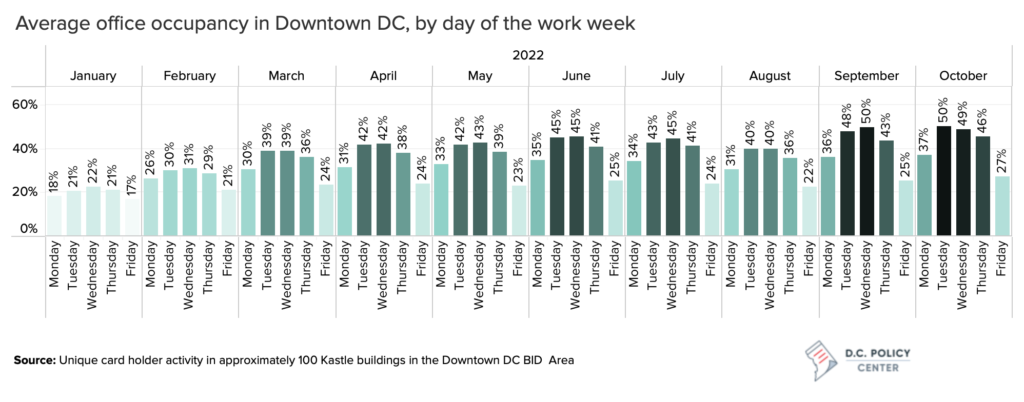

When COVID-19 first began, downtown offices emptied out. Since then, while many aspects of our lives are back to pre-pandemic norms, return-to-office is not one of them. Two years after the worst of the pandemic, even during the busiest days of Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, office occupancy in private sector buildings hovers around 50 percent.

In this context, attracting new residents and growing our population will become even more critical for the District’s future. The loss of commuters has impacted the local service economy and severely weakened the demand for office space in our downtown areas, resulting in losses in sales and commercial real property taxes.2 Thus, the city’s tax revenue has become even more dependent on the District’s residents and on economic activity in residential neighborhoods.3

Historically, the high cost of housing has been one of the key factors that pushes residents out of the city.4 Even without significant in-migration, housing prices in D.C. have remained persistently high, suggesting that producing more housing and creating more residential neighborhoods are necessary to keep existing residents, and attract new residents—including residents of all income levels.

D Zones have offered an exciting opportunity to expand housing in the District of Columbia over the past 20 years, but most new housing downtown will have to come from conversions.

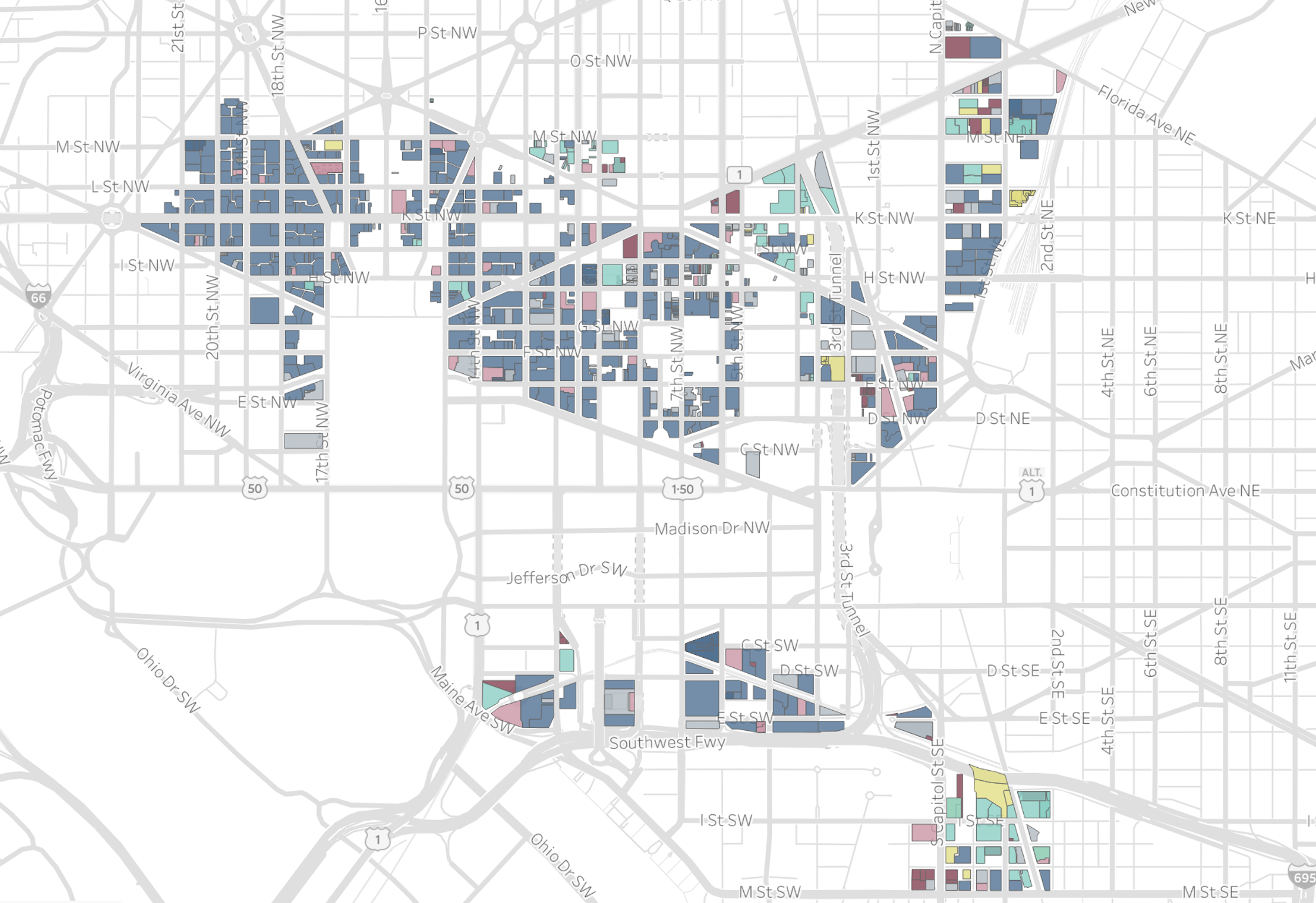

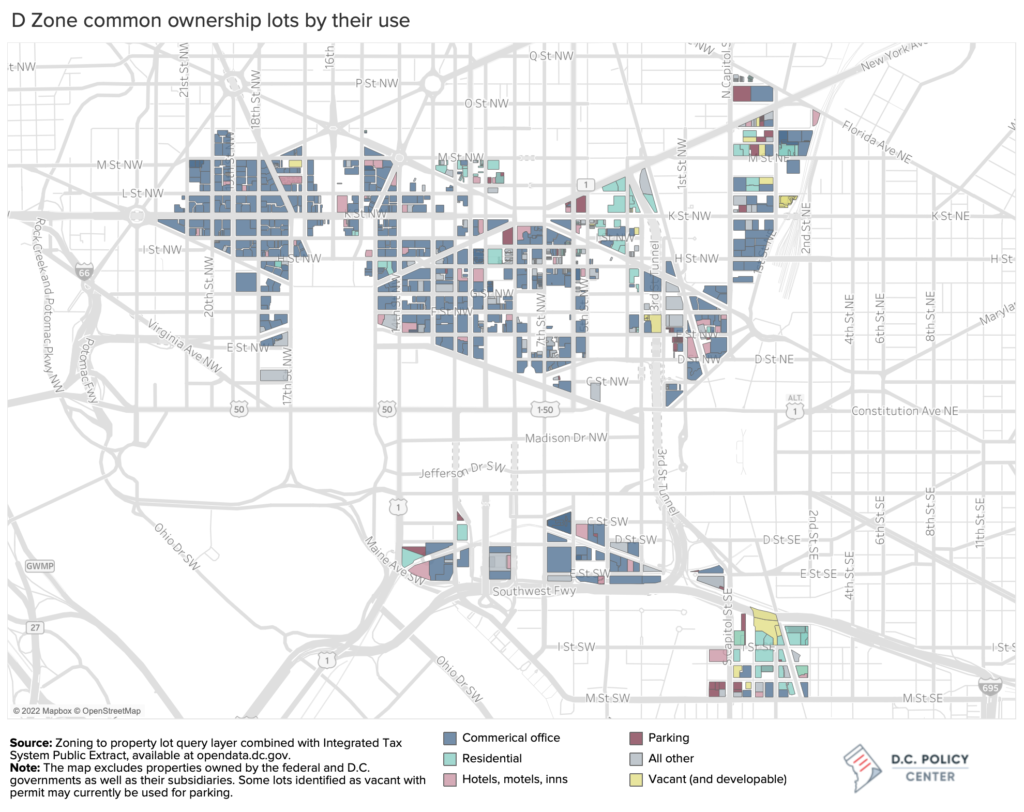

The production of housing in the D Zones has been strong but limited to a few pockets located in the Capitol Riverfront area, NoMa, and Mount Vernon Triangle, which are all new residential neighborhoods.

The D Zones have 1,048 tax lots (excluding those owned by the federal and District governments and their subsidiaries) and among those, only 104 buildings are in residential use. Of these, 48 are high-density properties located in Capitol Riverfront, NoMa, or Mount Vernon Triangle, all built after 2000. The remainder includes a handful of legacy multifamily buildings (18) scattered throughout the rest of the D Zones, three smaller walk-up apartment buildings, eight small buildings converted to flats, and 27 single family homes, some of which are no longer serving as homes but are now stores and small offices.

Commercial office buildings (530 in total), on the other hand, account for over half of all the properties in the D Zones. The remainder are retail stores, entertainment venues, restaurants, museums, school and dorm buildings, and other commercial buildings like banks.

There are only handful of buildable lots remaining that are vacant or being used as surface parking lots, that could be developed. This means new residential units in the D Zones will, as a practical matter, have to be in the form of office to residential conversions.

To this day, conversions (or complete redevelopment of office buildings) have been rare, and only a handful of them are in the D Zones.

Since 2002, the District has seen 19 conversions (including those under construction), and among those, 12 are residential conversions.5 These conversions have created 2,459 housing units. Among those, 272 or about 10.6 percent are affordable, but this is largely due to a single project (Jubilee House with 176 units that benefited from subsidies and is entirely dedicated to affordable housing). There are five other residential conversion projects that are in the works; with 1,342 residential units, 9 percent of which will be affordable. These new projects are located where residential demand is strong: along Wisconsin Avenue in Ward 3, in Kalorama and along Georgia Avenue in Ward 1, in the West End in Ward 2, and near the Wharf and Navy Yard in Ward 6.

For conversions to be feasible many factors must come together.

Office to residential conversions are not commonplace, since they require a set of specific characteristics to be financially viable. These characteristics include the prospect of higher return on cost for residential conversion as opposed to continued commercial use, and a building with physical characteristics that are conducive to a residential transformation.

For the developer, the most important consideration is the rate of return that the stabilized net operating income of a project bears to the total cost of that project. The larger the gap between the rate of return between redeveloping a building as commercial as opposed to converting it to residential, the more difficult it is for residential developers to compete to acquire viable projects.6 In this context, the decision to renovate, convert, or rebuild depends on many market-based factors that the owner or a potential owner must take into consideration: expectations about the future demand for office versus residential, the extent to which the commercial office building is leased, financing costs, and construction costs. The physical characteristics of the building also play a significant role, and for some buildings (for example with large floorplates) conversions won’t be feasible. And if the rate of return on any type of redevelopment (commercial or residential) is less than a market rate of return (today about 6 to 7 percent), then no redevelopment will occur at all.

In its 2020 assessment of commercial to residential conversions, the D.C. Office of Planning correctly found at the time that conversion opportunities in the District are limited, but identified certain feasible markets, which did not include D Zones.7 In its analysis, the higher commercial values and the structure of office buildings made D Zones a less likely candidate for conversions.

Deteriorating conditions in the downtown office segment is making conversions a more likely possibility.

Historically, the return on cost of developing commercial buildings was greater than developing multi-family in downtown areas. This is how downtown became an office center. But since the beginning of the pandemic, the office market in downtown has experienced significant and persistent setbacks:

- Increased vacancy: The office vacancy rate in the Central Business District, for example, now stands at 17.7 percent, up from 10.6 percent in the last quarter of 2019.8

- Increased distress: Of the 733 large office buildings in the parts of the city with heavy office presence, 137 have vacancy rates that are over 25 percent; and if leasing activity does not increase, this number may go up to 238.9

- Lackluster leasing activity: Net absorption has been continuously negative in the Central Business District since 2019, and the average time to lease has increased to over two years.10 The year-to-date net absorption in the CBD and East End submarkets was -174,763 and -391,485, respectively.11

- Equity flight: Institutional investor interest in D.C.—which kept the city strong during the 2007-08 Global Financial Crisis—has declined significantly as secondary and tertiary cities have become far more important to institutional investors.12 Many of the traditional D.C. institutional investors are bypassing the city for new investments and are selling the properties they have.

- Financing drought: The lending market for D.C. office properties is virtually frozen. Institutional lenders (banks and insurance companies) are hesitant to lend on D.C. office assets that are empty or poised for development without recourse or additional collateral.

The result is that some office buildings will stay empty because the office rents do not justify the capital needed to renovate an antiquated building. These factors, combined with the city’s interest in revitalizing office heavy downtown areas in D.C., have increased the interest in residential conversions.

The work of creating housing downtown should start with an analysis of what is feasible.

The Office of Planning and other agencies in the city, along with the D.C. Council, have an opportunity to put policies in place that can support, and do not further burden, office conversions. But this work should start with an analysis of what is realistic and feasible. This can be done in many ways, but all will require collaboration with private sector partners to better understand motivations for taking on such projects.

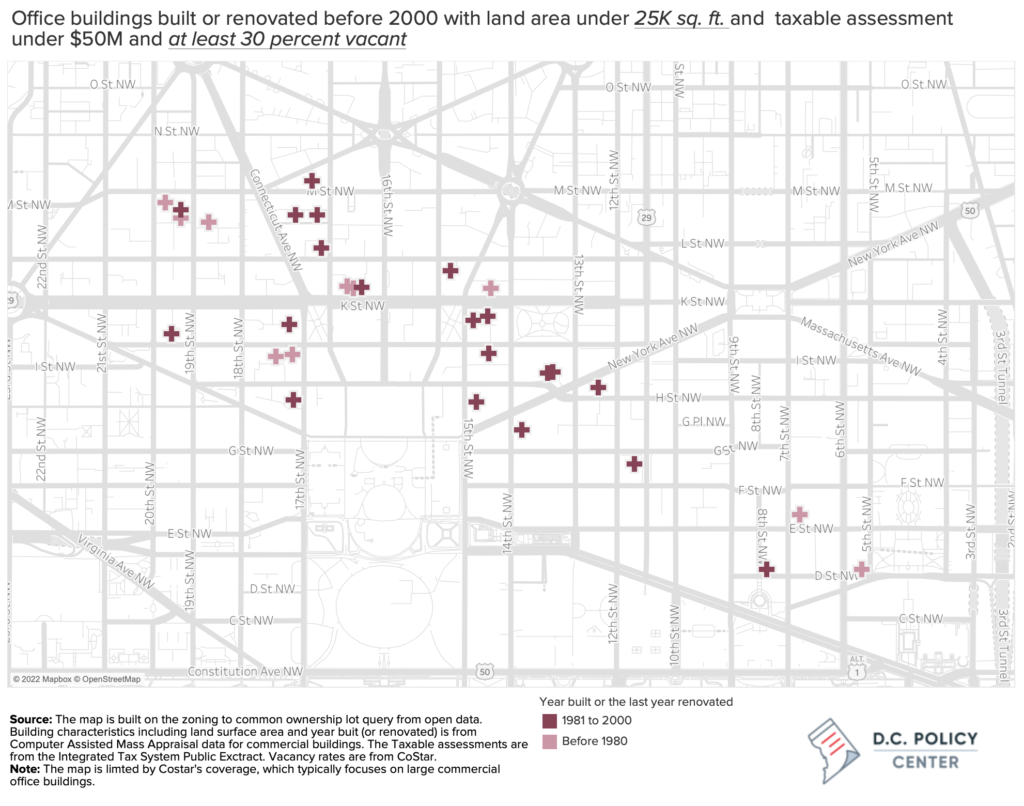

This exercise produced 33 potential commercial office buildings.

For example, the D.C. Policy Center aggregated multiple sources of data to identify existing buildings that might be good candidates for conversion. Our criteria included older buildings (built or renovated before 2000), on smaller lots (less than 25,000 square feet of land area), with high vacancy rates (30 percent or more), and lower assessed values (under $50 million).

The point of this exercise is to show that the universe of buildings that might be candidates for conversions could be surprisingly small. This means that: (1) the approach to policymaking should not be blanket mandates or requirements, but rather a deep engagement of the owners of buildings that are possible to convert, and (2) encouraging development in the D Zones outside of the downtown core is critical for the supply of new housing and therefore the financial health of the city.

Building a strong pipeline for housing—including affordable housing—in D Zones is a matter of policy, and not zoning.

Many zoning areas in D.C. have a lower height and density limit than what is allowed by the federal Height Act. These are the areas where Inclusionary Zoning operates because there is the ability to grant projects extra density in return for affordable units. But this is not the case for D Zones.

D Zones already allow development as dense as the Height Act permits and most of the construction in D Zones are already built to the Height Act limits. As such, without federal intervention, the only potential means of increasing housing in D Zones is through policy, and not zoning.

In this context, the most important thing the D.C. government can do is articulate its policy goals regarding housing in D Zones: Is it to increase housing units? It is to create a more mixed-use environment in parts of the city where that are made up of office buildings? Is it to revitalize parts of the city that have old buildings or little street level activity? Is it to create affordable housing? These goals can sometimes work against each other.

Given the very few potential conversion candidates, and the limited supply of vacant D Zone sites within and outside the downtown core, government policy should be to encourage the production of new housing. And to support the goal of increasing affordable housing, government policy must provide cost savings or benefits to developers to offset the cost of including affordable units in their projects. These actions also fall in the realm of policy, and not zoning.

The Office to Housing Task Force found that developers of residential conversions could be assisted through current federal incentives, especially increased Low Income Housing Tax Credits for projects located in Difficult to Develop Areas and Qualified Census Tracts when they include affordable units. Locally funded subsidies could come through various programs such as local preservation funds, the Local Rent Supplement Program, property tax abatements, project-based subsidies, or grants.

Blanket IZ requirements will discourage conversions in D Zones and other planned ground-up residential development.

At present, D Zones are excluded from Inclusionary Zoning requirements. This is because Inclusionary Zoning is based on the idea of a trade: the developers include affordable housing units in their buildings in return for increased density. But because D Zones already allow for maximum density, there is nothing to trade: imposing IZ requirements on D Zones—as proposed by the OAG—will be a pure cost, and will likely discourage conversions, which, as pointed out, may already need subsidies if they are to include affordable units. Such an imposition would also have adverse impacts on development of multi-family projects that are already in the pipeline in parts of D Zones outside the downtown core (Capitol Riverfront and NoMa), where there has been tremendous development in the past 10 years. The real property tax alone on the new development could create sufficient revenue for local rent subsidies.

Importantly, the OAG proposal runs against the policy direction of the Mayor and Council to ensure a downtown recovery, in part, through a great deal more of residential development. For example, this past budget season, in support of creating more residential development in D Zones, the D.C. Council approved a small tax abatement ($2.50 per sq. ft) to developers of residential property in some parts of the D Zones.13 The OAG proposal would nullify their work and discourage housing production in D Zones.

If the goal is to implement Inclusionary Zoning in D Zones, further zoning action is necessary to increase allowable FAR in D Zones so the program can operate as intended. This would possibly require Congressional action to allow for taller buildings in D Zones. Otherwise, the extended IZ requirements to D Zones, as proposed by OAG, will make housing production more expensive, and therefore will result in fewer units, including fewer affordable units.

About the data

The analysis of D Zone lots relies on a number of data sources including.

- Zoning to Property Lot Query Layer available at Opendata.dc.gov

- Integrated Tax System Public Extract available at Opendata.dc.gov

- Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal data for Commercial, Condominiums, and Residential

- CoStar data (not publicly available).

The analysis identified all common ownership lots that are within D Zones and matched them to their taxable assessment and property characteristics information (use type, land area, last year built or remodeled) using SSL identifiers. Building level vacancy rate information is from CoStar and this information is not available for all commercial buildings. When the criteria for vacancy is removed from the query, we identified 250 commercial lots that are under 25K sq. ft. in land area and assessed below $50 million.

Endnotes

- For various data updates on inflows and outflows from various metro areas, see Whitaker (2022) Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Cause an Urban Exodus? Data Updates for Tables and Figures.

- For an analyses of the impact of remote work on D.C. see the two-part essay by McConnell & Sayin (2022). Remote work and the future of D.C. (Part 1): How is remote work changing the geography of work in the District of Columbia? and (Part 2): What does remote work mean for the District of Columbia’s tax base?

- Per information from the OCFO, retrieved from revenue chapters of the budget books for various years. For example, in 2021, income taxes accounted for 38 percent of D.C.’s gross local fund revenue. This is a 6-percentage point increase from 2019. Income tax collections have increased during the pandemic largely due to two reasons: the increase in wages earned in the city because of inflationary pressures on salaries, and the performance of the stock market. The September 2022 revenue estimate issued by the Office of the Chief Financial Officer reduces income tax collections for Fiscal Year 2024 and 2025.

- Sayin (2015). Residents move in for jobs, move out for housing. District Measured. Available at https://ora-cfo.dc.gov/blog/residents-move-city-jobs-move-out-housing

- This number also includes the redevelopment of land under office use as mixed-use residential at the Fannie Mae site. For details, see D.C. Office of Planning (2020). Assessment of Commercial to Residential Conversions in the District of Columbia.

- For an illustrative example, see Kathpalia and Sayin (2021), Examining office to residential conversions in the District.

- D.C. Office of Planning (2020). Assessment of Commercial to Residential Conversions in the District of Columbia.

- Data from Costar.

- D.C. Policy Center analysis of tax lots and Costar data.

- Data from Costar.

- JLL Q3 2022 Market Report.

- AFIRE International Investor Survey, 2022.

- This abatement is not for the entire D Zones, but targeted to the area roughly bounded by Dupont Circle, Washington Circle, the intersection of 9th ST NW and Massachusetts Ave NW, and the intersection of I St. NW and Pennsylvania Ave NW.