The evolving federal workforce and its changing role in the D.C. economy

It’s no secret that the federal government is a major employer in the Washington, D.C. area, and it likewise has an outsized effect on the District’s economy. The five-week partial federal government shutdown that ended earlier this year cost the D.C. government $47.4 million in lost revenue, according to the Office of the Chief Financial Officer, and another showdown over the federal debt ceiling could be brewing for this fall.

Amidst pending sequestration cutbacks and seemingly perennial shutdown threats, it’s worth exploring the federal government’s changing role in the District’s economy. To examine recent trends in federal employment, we reviewed historical data reported by the Labor Department and Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

What emerges is a picture of a workforce that, while not as crucial to the District’s economy as before, is increasingly experienced and educated. The federal workforce is also older than in the past, and has defied expectations that agencies will empty out as their workers retire en masse upon reaching retirement age. This means that the D.C. region has been able to hold on to highly paid federal workers for longer than many expected, although the general trend of moving the federal workforce out of the District, and more recently, out of the broader metropolitan area, continues to persist.

Trends in federal employment

While the overall size of the federal workforce hasn’t grown much in recent decades, federal agencies and their individual workforces look a lot different in a number of ways, and perhaps nowhere is this more visible than in D.C.

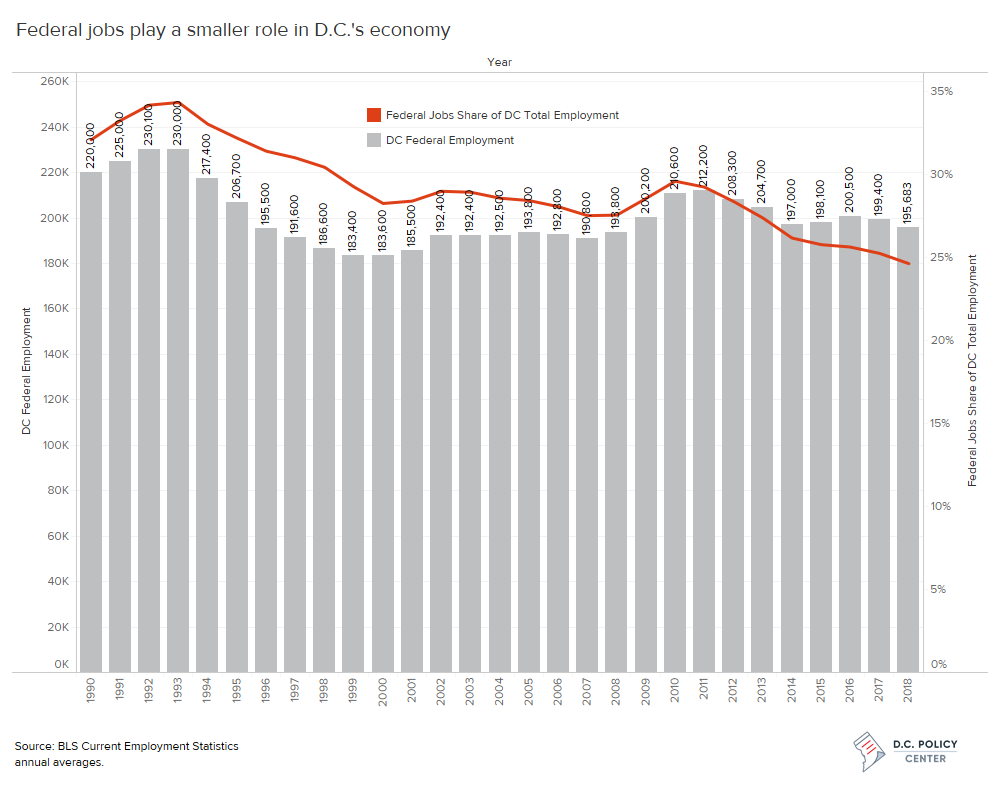

Today, Labor Department estimates show just under 200,000 federal employees, including the Postal Service, work in D.C. That figure has remained flat for five years, fluctuating little over recent decades. Peak employment from the Labor Department data, which covers the period since 1990, occurred in 1992-1993, when about 230,000 employees were stationed in D.C. Nationally, the federal workforce has similarly downsized and the proportion of workers based in D.C.—about 7 percent—has remained fairly consistent over time.

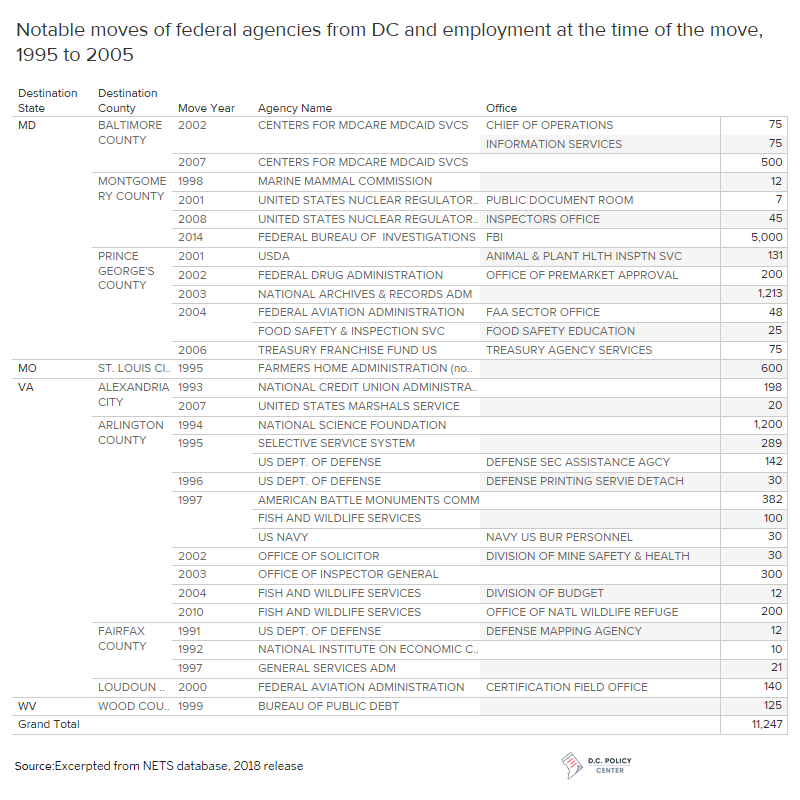

It’s a different story within the region, however, as the District’s workforce hasn’t quite kept pace with surrounding jurisdictions over the long term. In the early 1990s, D.C. accounted for about 63 percent of the metro area federal workforce. This share has since gradually declined to just over half today, largely a result of several agencies expanding their footprint in Maryland and Virginia, or moving out of the region entirely.

Most recently, for example, the Department of Agriculture is soliciting proposals to relocate its research divisions out of the District. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue announced earlier this month that the agency had narrowed its list to sites in 28 states, including two suburban Maryland locations. Similarly, the federal government is seeking a new home for the FBI headquarters, currently the J. Edgar Hoover Building in downtown Washington. Officials previously targeted two potential sites in Maryland and another in Springfield, Va., but the Trump administration has since offered a new proposal keeping most employees in the District, while shifting a few thousand staff to other parts of the country. Growth in federal contracting over the long term further accounts for some the shift in employment.

For its long-term economic vitality, it’s crucial that the District broaden its labor market to other industries. Virginia and other states heavily reliant on the federal government have long sought to diversify their economies.

Clearly, D.C. federal employment—more than 30,000 below its recent peak—isn’t going to take off anytime soon. D.C.’s private sector, though, started to accelerate around 2000 and has enjoyed steady job gains since. As a result, reliance on the federal government as a source of jobs is gradually diminishing. By our calculations, federal workers now account for a quarter of D.C.’s employment base, down from about a third as recently as the mid-1990s.

Trends for agencies and occupations

For a look at shifts across individual agencies, we’ll rely on data from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) covering full-time, nonseasonal workers.

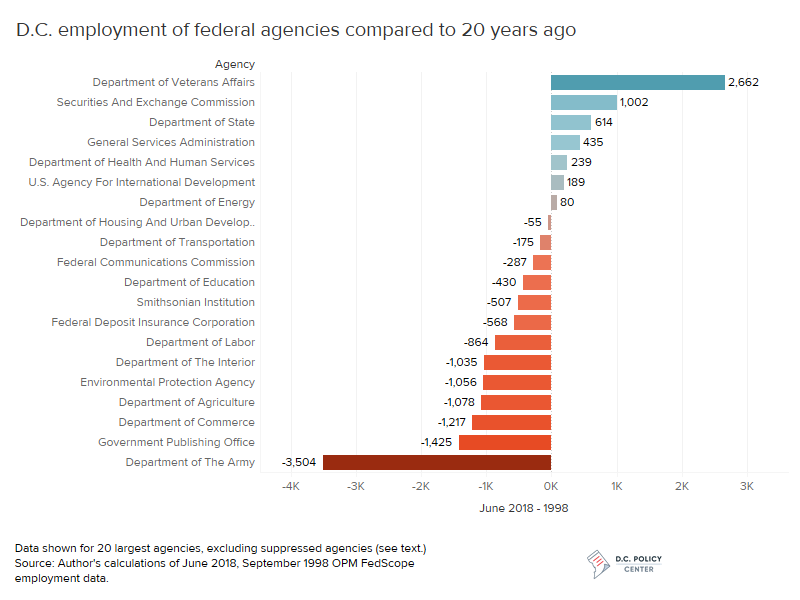

D.C. employment across most agencies has declined from 20 years ago. Army civilians based in D.C. are down by about 3,500, stemming primarily from the former Walter Reed Army Medical Center relocating to Bethesda in 2011. The U.S. Government Publishing Office, which changed its name in 2014 to reflect a shift away from printing, has experienced a substantial dip as well, employing about 1,400 fewer workers than 20 years ago. Other agencies with larger declines include Commerce, Agriculture, and the EPA. D.C.-based military employment has remained mostly flat in recent years, although it’s down from a few decades ago.

The agency that has grown the most in the past two decades is the Department of Veterans Affairs. It’s up about 2,700 employees over the past two decades, but has downsized slightly in recent years.

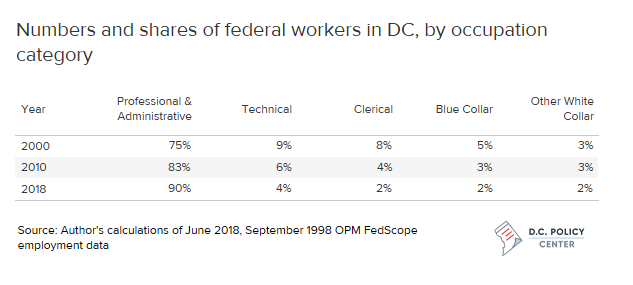

Data further show changes across different occupational categories, as defined by OPM. Likely the most noticeable shift has been the disappearance of clerical jobs as technology has replaced many of their duties. Today, the federal clerical workforce in D.C. is less than a quarter of what it was in 2000, accounting for less than 2 percent of the total D.C. federal workforce (down from 8 percent).

The aging federal workforce

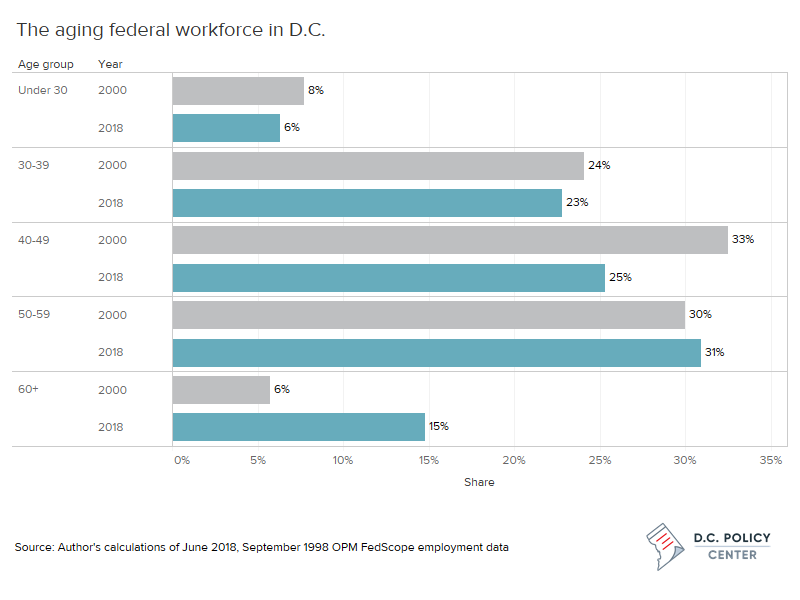

Just about every public or private employer has felt the effects of a large segment of Baby Boomers nearing retirement, and the federal government is no exception. Back in 2000, federal workers between the ages of 40 and 59—reflecting nearly all Baby Boomers—accounted for about 63 percent of the District’s federal workforce. That age cohort’s share has since dropped to about 56 percent.

While many Boomers have already retired, the “retirement tsunami” that had been predicted to begin in the early 2000s has not happened. In fact, OPM’s figures show that about 46 percent of the D.C. federal workforce is over the age of 50, and 15 percent is age 60 or older. Never in recent decades have local federal agencies relied on as many workers who are either eligible to retire or nearing retirement age. By comparison, less than 6 percent of all D.C. workers were age 60 and up in 2000, and those over the age of 50 were about 36 percent. (Retirement eligibility for federal workers varies based on their date of birth, years of service and agency.)

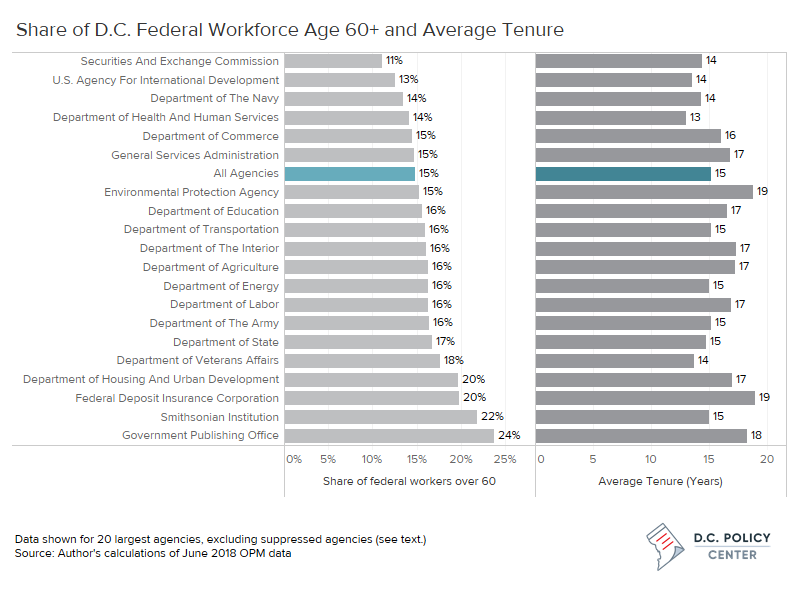

Some agencies have seen the upswing in ages more than others, as the chart below shows. At the Department of Housing and Urban Development, for example, about 20 percent of D.C.-based employees are 60 and over. For the Smithsonian Institution, the share is nearly 22 percent.

Relatedly, years of experience on the job further vary across agencies, although the presence of older workers does not necessarily mean those workers have longer tenure. On the high end, the EPA’s average length of service is about 19 years—four years longer than the government-wide average, even though its share of workers over the age of 60 is the same as the average of 15 percent for D.C.-based employees. Other agencies with longer tenures are FDIC and HUD, along with the Government Publishing Office, with nearly a quarter of its workforce over the age of 60.

Education attainment climbs higher

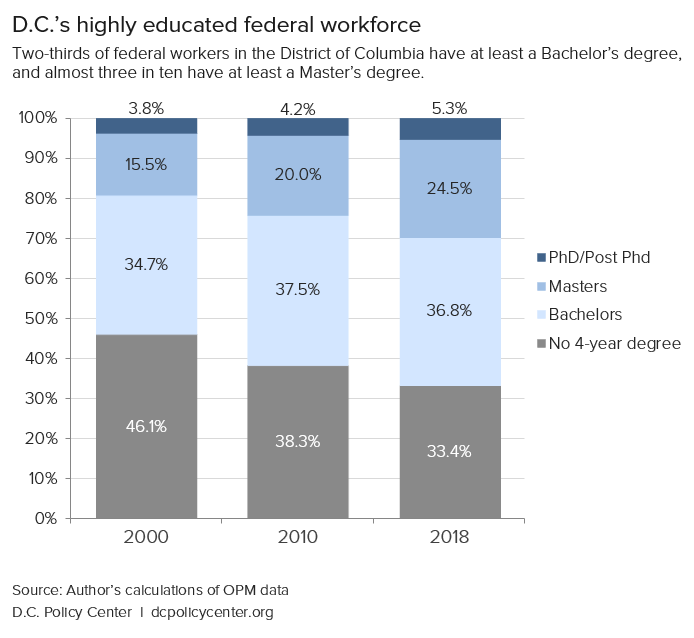

Another mark of the federal workforce is just how highly educated it is. Two-thirds of D.C.-based federal workers hold at least bachelor’s degrees, significantly higher than national rates for most private sector occupations. What likely stands out most is the large number of local employees attaining advanced degrees, with the latest OPM data showing 30 percent hold Master’s degrees or higher.

Overall, only a third of the D.C. federal workforce lacks at least a bachelor’s degree, including many with some college or associate’s degrees. This represents a sizable decline from 2000, when 46 percent of workers were without bachelor’s degrees. It also mirrors national trends, as Americans have increasingly pursued college degrees in recent decades.

About the Data

All statistics refer to federal jobs located in D.C., unless otherwise indicated. Totals for the entire workforce represent estimated annual averages published by the Labor Department. This includes a large number of U.S. Postal Service (USPS) employees.

Agency-level data and statistics reflecting characteristics of the workforce were obtained from OPM’s FedScope database. All data refer to only full-time, nonseasonal workers employed in the District of Columbia. Figures represent totals current as of June, while data prior to 2010 are current as of September of the corresponding year. OPM suppresses the locations of some employees not reflected in the data. Nationally, more than half of all DOJ and DHS employees, along with nearly half of OPM staff, have suppressed locations, for instance, so they are excluded from the charts in this article. Additionally, OPM’s database does not report employment figures for USPS and some small agencies.

Feature photo by Ted Eytan (source).

D.C. Policy Center Fellow Mike Maciag crunches numbers and writes for Governing magazine on a variety of policy issues relating to state and local governments. He holds a master’s degree in public administration from George Mason University and undergraduate degrees in journalism and computer science from the University of Dayton. Follow him on Twitter at @mikemaciag.