First Take is a regular opinion column by D.C. Policy Center Senior Fellow David Brunori.

I have long been a fan of the property tax. I think it is the ideal way to fund local general fund spending. But the property tax is rarely a sound vehicle for targeted spending or redistributing wealth. Unfortunately, the Council of the District of Columbia is proposing to do just that in its Fiscal Year 2019 Budget proposal. That measure, which passed the first reading on May 15, will, among other things, raise the property tax rate on all commercial property valued over $5 million to 1.89 percent. The current rate is 1.65 percent for the first $3 million in value and 1.85 for amounts over that. The proposal will eliminate this tiered tax rate and replace it with two classes based on property values.

The proposal exacerbates value differentials.

Few public finance experts would say that differentiating rates based on value is a good thing. This proposal will exacerbate the differentials in tax rates by imposing a new rate of 1.89 percent on properties valued over $5 million. Examining the publicly available real property tax assessment data, the D.C. Policy Center estimates that if implemented today, this new proposal would have generated about $37 million, and an additional $22 million revenue over what the Mayor proposed in her budget. That money will be used mostly to help the District’s contribution to Metro. Some of it will be used to fund the Commission on the Arts and Humanities and the Creative Economy Enterprise Fund. Some of it will fund a property tax circuit breaker for small retail operations. Metro of course needs to be funded. And while I am not as familiar with the Commission or the Fund, I am sure they are worthwhile endeavors.

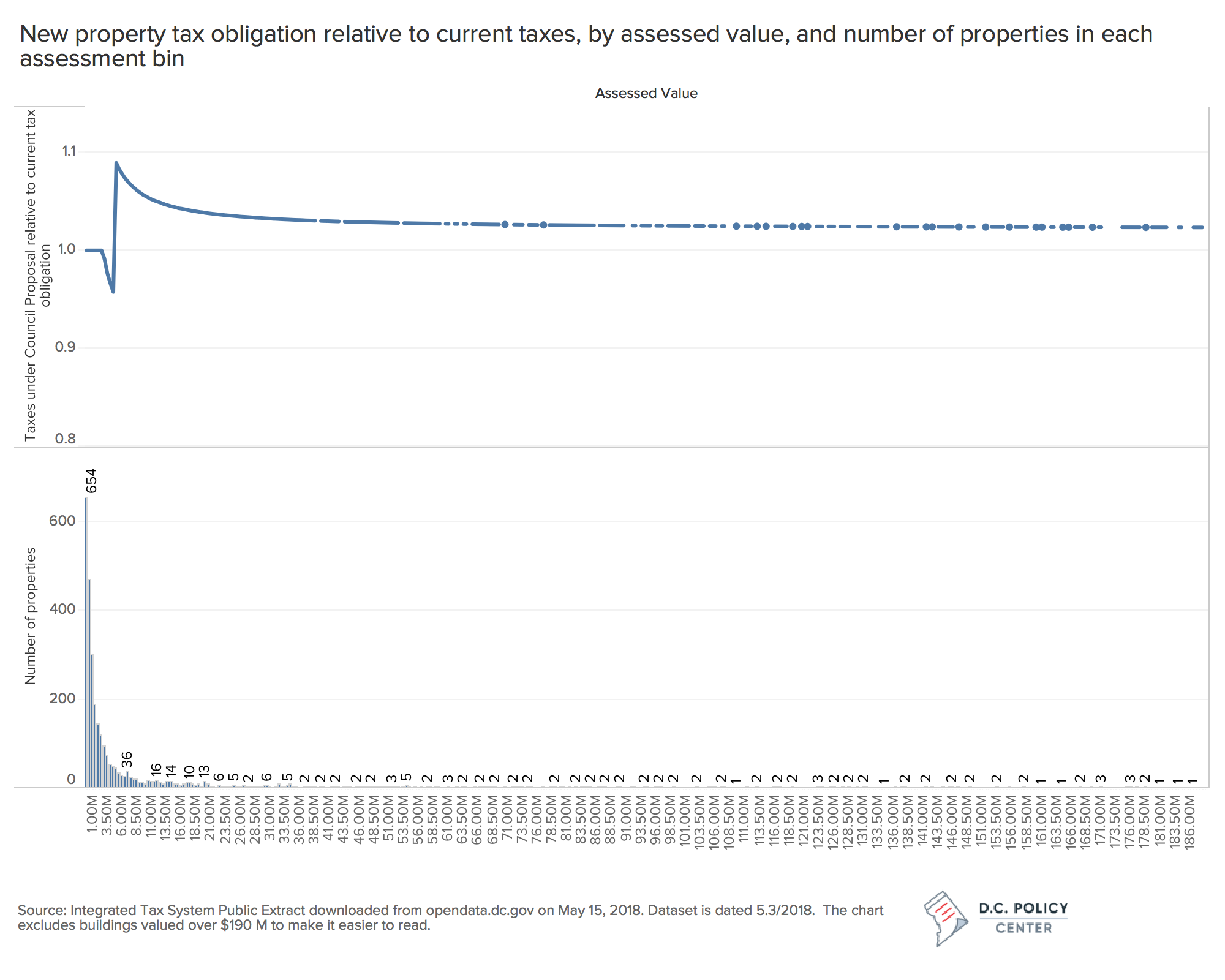

For those with assessed values around $5 million, this is a steep tax increase.

Here is how lopsided this policy proposal is:

Data show that of the 40,000 properties on the District’s tax rolls, 5,433 are identified as commercial real estate on our tax rolls.[1] These, collectively, are assessed at $149.06B in value. That is, commercial properties make up 13 percent of District’s property stock but account for 46 percent of the assessed value. Not all these properties are taxable. In the commercial stock 2,210 properties are exempted from taxes either because they are owned by the District or the federal government, or they have qualified for some type of tax exemption because of how they are used (schools, religious organizations, etc.), or because the DC Council has passed a bill to exempt them from property taxes. When we take these out, we end up with 3,224 properties that pay $1.39B in property taxes—that is 53 percent of all property tax collections in the city.

Under the proposal 1,841 properties valued below $3 million will see no change in their tax rates. According to the tax rolls, there are only 300 properties valued between $3 million and $5 million, and we estimate that they will collectively receive a tax cut of about $440,000 compared to what they pay today. That is a 2.3 percent reduction. But for those valued slightly more than $5 million, this is a steep tax increase. We count about 246 properties valued between $5 million and $10 million. Collectively their taxes will increase about $2.1 million or by about 7 percent. Finally, 837 properties with assessed values over $10 million will pay an estimated $35 million more compared to current structure (and about $20 million more compared to what the Mayor had proposed). This is a 2 percent increase.

Setting aside the strange cliff in tax obligations, the question is whether a new tax on highly valued real property is the appropriate way to pay for these public goods. First, further differentiating rates based on value essentially puts the District government in the position of favoring one type of investment over others. Governments rarely get that right. Second, picking a particular group to fund worthwhile public services is politically attractive, but nonetheless unfair. We see this phenomena across the country where a minority (smokers, drinkers, drivers, the “rich”) are asked to pay for something we all want. There is nothing good or just about that. If Metro is important to the District — and I certainly think it is — shouldn’t the city be paying for it with broad based taxes? Of course, taxes go up and every property owner takes that risk. But in this case, only some property taxes are going up. The same bill will lower property taxes for others.

Setting aside the strange cliff in tax obligations, the question is whether a new tax on highly valued real property is the appropriate way to pay for these public goods. First, further differentiating rates based on value essentially puts the District government in the position of favoring one type of investment over others. Governments rarely get that right. Second, picking a particular group to fund worthwhile public services is politically attractive, but nonetheless unfair. We see this phenomena across the country where a minority (smokers, drinkers, drivers, the “rich”) are asked to pay for something we all want. There is nothing good or just about that. If Metro is important to the District — and I certainly think it is — shouldn’t the city be paying for it with broad based taxes? Of course, taxes go up and every property owner takes that risk. But in this case, only some property taxes are going up. The same bill will lower property taxes for others.

Who pays the commercial property tax?

What the Council should really consider is who will be paying the new tax. Political leaders often think that taxing commercial real estate is a way to export tax burdens to rich investors out of state. And in fact, a lot of buildings worth more than $5 million are owned by people who do not live near the city. Getting a rich guy in New York to pay for Metro seems like a winner. But that is not what is going to happen. Most of those buildings are rented – to other commercial enterprises. The owners will try to pass every penny of that estimated $37 million on to their tenants in the form of higher rent. In fact, this is written in many lease agreements where the owner explicitly passes the real property tax risks to the tenant. Most likely, it will be District employers and residents, rich and poor, who end up paying. They will think twice before renewing their leases. And when that happens, and when property owners cannot any longer pass the tax on to their renters, this measure will likely deter further investment. Less investment will be a terrible outcome in a city that derives much of its fiscal health from its appeal to job creators.

Funding Metro is critical. But the Council should consider whether imposing taxes on one of the most important economic drivers in the city is the way.

Note

[1]In addition, we found 213 properties identified as mixed use, with a combined assessment in the commercial parts of the building equaling $415M.

Feature photo by Ted Eytan.

David Brunori, who writes the regular column First Take, is a partner in the Washington office of Quarles & Brady LLP and a research professor of public policy at The George Washington University. He is a nationally known expert in state and local tax and public finance. He also serves as a commissioner on the District’s Tax Revision Commission.