Harriet Tregoning has been a force in planning and policy locally and nationally for quite some time. After founding the Smart Growth Network during the early phase of her career at the Environmental Protection Agency, she served as Secretary of Planning for the state of Maryland. This was followed by her appointment as Director of the D.C. Office of Planning from 2007 until 2014, serving two successive mayors. During her tenure, Tregoning advocated for multi-modal transportation options and increased density; it was under her watch that D.C. started its successful bikeshare program and its complete streets policy. Following these local roles, she returned to the federal government as Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Office of Community Planning and Development at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in the final years of the Obama Administration.

Since the 2016 election, Tregoning has stepped away from her role at HUD and has become, among other things, an advocate for thoughtful planning around autonomous vehicles. As part of this advocacy, she recently submitted an element (PDF) to the D.C. Comprehensive Plan focused on planning for the deployment of autonomous vehicles. I recently sat down with her to talk about what this “shot across the bow” means, what D.C. is already doing, and what it could be doing better to prepare for its future, related to autonomous vehicles and beyond.

Q: What prompted you to write and submit a comprehensive plan element focused on the land-use and regulatory implications of autonomous vehicles?

Tregoning: Autonomous and connected vehicles are coming and they have tremendous implications for cities; their impact will be felt well within a comprehensive plan’s 20+-year planning horizon, [but] they are not yet included in the District’s Comp Plan. I submitted this new element in hopes of getting the conversation started and to reinforce that this technology is coming up in the near term. If we get autonomous vehicles right, there’s lots of potential benefits including cheaper transportation, more convenience for residents, greater mobility for seniors, less car storage/parking, even the transition of parking and some right-of-way space to other purposes.

Q: A big fear with autonomous vehicles is that we’ll have a huge opportunity to repurpose the public right-of-way, but cities may not have the backbone to say, “we want this right-of-way to stay public and/or go towards green infrastructure or active transportation modes.”

Tregoning: Well, cities share a lot of information and they compete with one another. Mayors are both competitive but also generous about sharing [information]. So that’s why it’s important for some leading cities to get out in front of this and chart a path forward. I think the other real danger is state preemption. A lot of laws are being written in state capitals, especially when the state house politics are different than the capital city’s, to prevent them from implementing certain things. State legislatures are set up to mimic the federal Congress, which gives a lot of power increasingly to sparsely populated parts of the country, and parts of each state. Therefore, as we plan for autonomous vehicles, we need to do city-rural pilots in states. We need to early on be thinking of that, because imagine what autonomous vehicles could mean for providing mobility to aging farmers in those communities—it could be huge. You don’t need to have super frequent transit to serve them, but autonomous vehicles could open the door for reliable transit in rural areas for those who cannot drive. That needs to happen to keep this technology from being a casualty of the urban-rural political divide and because it will improve the lives of rural residents. It needs to happen even as people are thinking about what revenue sources will replace those that will disappear—gas taxes and parking fees.

Q: And traffic violation, tickets, and fines, etc.?

Tregoning: Right, well some of those are state revenue streams and some of those are local revenue streams. Especially for state revenues, you need state legislators to be able to see a future and an interest in autonomous vehicles beyond preempting cities.

Q: That’s a great point about making the two go hand-in-hand so it doesn’t become more of an urban-rural divide than it already is. I guess if that doesn’t happen, states would preemptively make laws that require that roads stay committed to automobiles whether they’re self driving or not.

Tregoning: Or do other things to tie the hands of localities in places where this is going to be happening first, and by shifting the direction of cities on the leading edge, it could shift the way we use autonomous vehicles everywhere eventually.

Q: Do you think the culture in D.C.’s government and at DDOT is supportive of the idea of repurposing streets for the broader public good as opposed to just for moving cars through them?

Tregoning: Yes, definitely. I shared copies of this Comp Plan submittal around D.C. government, and I know DDOT is already working on this issue—and I think they’re open to this, as well as every other aspect of transportation innovation. Certainly since I was there, planning and transportation have had a very close working relationship because most people in cities (at DDOT and elsewhere) might say that the best transportation plan is a good land-use plan.

Q: In the element, you wrote about the value of data-sharing. Uber and Lyft are notorious for not really sharing their data, or not doing so very willingly. Is it feasible to say that, if we’re going to open streets up to self-driving cars, rideshare providers will need to give their data to the municipalities in which they are operating so they can plan with it?

Tregoning: I think data won’t just be important for planning purposes, but how the companies charge for use of the service or how municipalities charge for use of the street facilities would be based on data that only those companies would have. Things like charging less per-person when the ride is shared, or charging more for zero-occupancy vehicle-miles-traveled cannot happen without access to this data.

For instance, we already have a vacant property tax in D.C., because a vacant property on a street is a bad thing. The tax rate on a vacant property is up to 10 times the property tax rate of a property that is in use. The principle already exists in our city. So an empty circling vehicle would also be the same type of dis-amenity, and thus should be charged accordingly—but in order to do so, we’d need to have the data.

Q: Uber did include D.C. in Uber Movement as one of a few cities they released data on, correct?

Tregoning: They did, and rightly so. Because D.C. is already doing a lot. There’s a work group headed by the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development. There’s a lot going on here with respect to automation, but it wasn’t in the comprehensive plan. Not just in D.C., but everywhere, everyone is focused on “the gee whiz technology and not focused on the land use. So that’s why I thought it was important to add a land use and autonomous vehicle element to the comprehensive plan.

Q: Do you think people are starting to look past the sparkly shiny technology and realize there are these land use and other tertiary implications that we need to think about?

Tregoning: I don’t know, I think not quite yet, but starting now, maybe. That’s why this autonomous vehicle element in the comprehensive plan was a shot across the bow to say, “hey, this is something we need to think about now.’

Q: How much of this needs to get done before these cars are on the road? How much of the stage needs to be set?

Tregoning: We need to be doing things right now. They’re meeting about it now, but we need things like “lay-by zones—essentially pick-up and drop-off zones in place of some street parking—now. We need to revamp our parking requirements for new construction to reflect reduced future demand now.

Q: Is it a “chicken or the egg challenge” because once AVs are more prevalent you won’t need as much parking, but until then I’d imagine it’s hard to get neighbors to give up parking spots for layby zones?

Tregoning: Well, our rate of car ownership is already dropping here. Existing rideshare services are already taking away some of the incentive for private car ownership and making it even more of a bad deal for people, right? Private cars are in use 5 percent of the time, parked 95 percent of the time—bad deal. So, it’s already manifested in our city that car ownership is a bad deal and rideshare services only make it more convenient to not own. That’s why I think we can start taking some parking for lay-by zones now.

Q: The data indeed shows that, every year, the folks that move into D.C. have fewer and fewer cars amongst them.

What do you think about the idea that autonomous vehicles could create this middle ground of transportation? Now, you either share a bus or train with a bunch of people or you drive your own car alone. Autonomous vehicles could pull some people away from solo driving but they may also pull some people away from transit and bring them to a middle ground where you share your ride with a car load of people rather than a train load.

Tregoning: Sure, there’s already Uber Pool, Lyft Line etc.

Q: Right, and what people are concerned about is that there will be more people who say, I’m willing to pay a bit more to not ride on a crowded bus or train, but I’m not willing to drive myself, so this is going to pull more people from the transit than it is going to pull from solo driving.

Tregoning: That’s why data is important, and that’s why it might make a lot of sense for the transit agency itself to be the operator of autonomous first mile and last mile solutions. It’s definitely true that the efficiency of a well-run Metro is going to best these other options, because there’s no traffic—you can’t beat it. So, the question is, who’s going to operate these middle-ground transportation services and are they going to be designed to be complementary or to compete with transit.

Q: Are you talking to folks at WMATA yet?

Tregoning: Yes. There’s openness to these ideas, but it’s all at a very early stage at this point.

Q: Are there any aspects of autonomous vehicles that are going to be especially great for Washington, D.C. in particular.

Tregoning: All of it. Only because, whether it’s great or not, it’s going to happen, and D.C. is a place used to change, used to transportation innovation. A lot of startups and transportation innovations (bike share, car2go) started here or are most successful here. This city is a place you would come to try new things and we’ve already shown receptivity to autonomous vehicles. D.C. also has a progressive government, so how we think about work, and what pilots we try with respect to work align with goals the city already has. This will be important given the potential labor displacement associated with autonomous vehicles. So overall D.C. is a good place to be with respect to autonomous vehicles.

Q: What’s your response to those who say, “won’t people just want to live further out because they won’t have to be focused on driving into the city? They’ll just ride in while on their phone or do whatever they want on the way in? Is that a concern? Does that temper your excitement for D.C.?

Tregoning: You know, it’s a degree of the same phenomenon that we already have. But look at it this way: for 6,000 years human settlement patterns looked pretty much the same. Until the automobile, it was essentially based on the walkable neighborhood. Three or four walkable neighborhoods became a village, and three or four of those became a town. Human beings have a preference to be around other human beings. There are wonderful things about being out in the wilderness, but loneliness and isolation are not something human beings do that well with. Autonomous vehicles will enable some degree of further sprawl, but I think if you also create incentives against private ownership of self-driving cars and zero-occupancy vehicles, that will also manage it.

Q: That makes sense. Essentially, we lived that way for thousands of years—there’s an innate preference for it—and we got away from it for awhile, but even without this technology, people are showing with their feet, and thus with the price of housing, their preference for living in cities again. That is reassuring to me.

Tregoning: Exactly.

Q: Are there any aspects of this technology that will have an effect on gentrification or the pace of gentrification in D.C.? Do you see any connections there?

Tregoning: People have imagined a dystopian future in which cities are filled only with rich people who have every convenience you can imagine, and the poor are shunted out to the edges of regions using old technology, trying to scrape together a living. That would be really horrible.

Q: So how do we prevent that?

Tregoning: Keep in mind that the second largest expense for most households in the U.S. is transportation. Already, in the District, households on average spend $9,000 per year on transportation. In Loudoun County they spend more than $20,000 per year on transportation. So, things that you would do to lower the cost of transportation actually make cities more affordable. This technology could be another step in that direction, especially if we could repurpose public land for more housing for more people.

In 1950, the average household size in the District was about three people. It’s just about two now. So, 50 percent fewer people per household, and that means we don’t have the density we used to have even with an identical or larger housing stock. Figuring out ways that people on fixed incomes can live in retirement in D.C. is just one of many challenges we need to sort out. There are all kinds of ways in which we could have better alignment between the assets and resources that we have and the people who could avail themselves of those assets and resources. None of it happens automatically, none of it happens simply through operation of the free market—from that we get the aforementioned dystopian scenario. But, if you put smart provisions in place you could end up better off than we are now.

Q: I hadn’t heard it in that clear of terms before regarding transportation costs in Loudoun County versus D.C.. If you think of it as a $10,000 annual subsidy to a family who moves to a walkable city like D.C.—that’s a game changer for a low-income family.

Tregoning: In the great recession, beginning in 2008, all kinds of cars started to drop off our DMV roles. I thought people were fleeing the city, but it turns out they were dialing down their transportation costs. Two-car households became one -car households, one car households became zero car households. And there were almost no bankruptcies or foreclosures in the District of Columbia. This was similar in Arlington and Alexandria.

Conversely, in places in our region where people had no transportation choices, they had enormous amounts of bankruptcy and foreclosure. They already had bought at the absolute limit of their affordability, and now someone lost hours or lost their jobs. So property prices plunged in parts of our region, but only dipped in the District. And then the rebound in D.C. proper was rapid and huge, and the city gained on its share of regional population and on its share of regional jobs post recession. The surrounding jurisdictions all subsequently opted to invest more in transportation choices and denser activity-centered development patterns in part because of that recent lesson in economic resiliency. We were in the same jobs and housing market, and yet these jurisdictions fared extremely differently.

Q: Because the person in the district could say “I need to save money, I can take the bus, its an option, I can bike to work, that’s an option. But in the suburbs, they could not.

Tregoning: Right, and they can say “I’ll just do this as long as I need to, I can always buy a car when things get better, and a lot of those people never did buy that other car because they realized they were just fine without it.

Q: One final question—is there any one autonomous vehicle topic that is especially understudied and that you, as a planner, wish you had data on.

Tregoning: I think it would be really great for some planners and designers to spend some significant time reimagining the public right-of-way and reimagining parking structures. I only permitted, when I was planning director, a single new standalone parking garage, but I made them design it to be retrofit-ready for housing. I get that it’s needed now, but if we don’t design for adaptation, we’re going to be stuck with stranded assets everywhere. Right-of-way is another field. The future of work is another. Another field—how to structure fees and taxes to pay for road maintenance when the primary source, the gas tax, is going to be obsolete. Did you hear that Volvo is going to go fully electric by 2019? That’s very soon.

Q: The parking ramifications most excite me. I think of my hometown of Greensboro, North Carolina and how much of its downtown is devoted to parking. However, if you can decouple being auto-centric from therefore meaning you also have to be parking-centric, which autonomous vehicles allow you to do, there’s a lot of smaller cities that are going to be willing to shift significant amounts of land away from parking.

Tregoning: There is a stepwise way to go. Here in D.C. we decoupled parking from dwellings, so all of our parking requirements are less than one for one, and they have to be sold and rented separately from the apartments. Because otherwise you embed the cost of parking in your housing cost, and those with sunk costs figure that they might as well keep their car, but if it’s an increment you can ditch, it changes the psychology without taking anything away. That’s the first step, giving people an economic choice, and it also changes it for the developer who could end up with a stranded asset—a parking space that no one wants. In every development, the parking demand is lower than the developer anticipated, and it’s sometimes lower than the planners anticipated. There’s actually a business in parking arbitrage now if someone wanted to do it. Because the requirements still exist, the bank still wants some degree of it, but in a given area there might be plenty of existing unused parking, because that’s not transparent where and how much there is. In cities like D.C., lots of parking is there that could still be used, instead of building new spaces.

Q: Thanks so much Harriet, for taking the time to talk with me about all of this.

Tregoning: Thank you for talking with me.

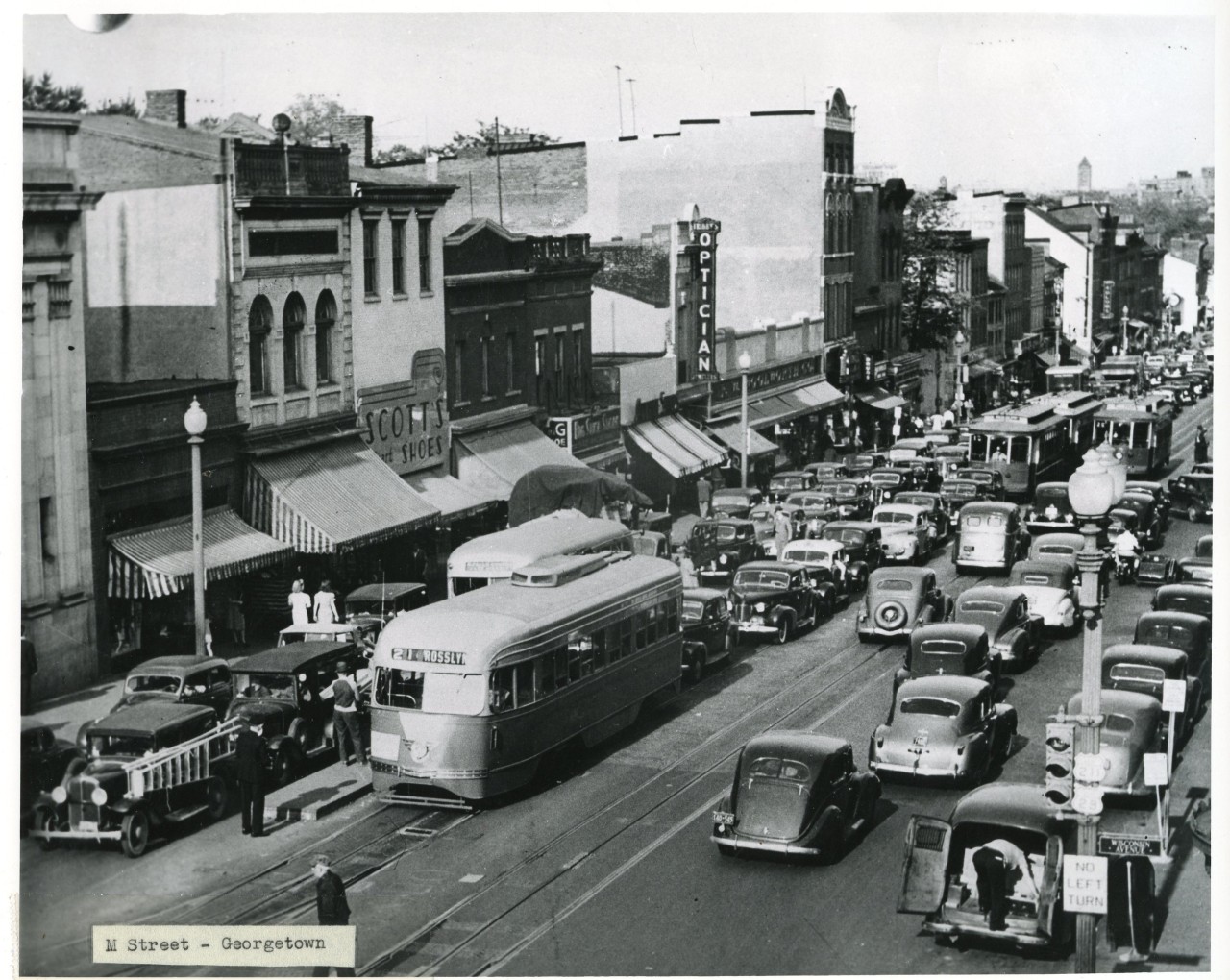

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. Feature photo of M Street in Georgetown from DDOT archives.

D.C. Policy Center Fellow Will Leimenstoll is an aspiring urban planner interested in how technology can help build more sustainable, economically vibrant, and equitable communities. He lived and worked in Bangkok, Thailand, Cape Town, South Africa, Auckland, New Zealand, and Durham, North Carolina before moving to the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Washington, D.C. He’s a native of Greensboro, NC and a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.