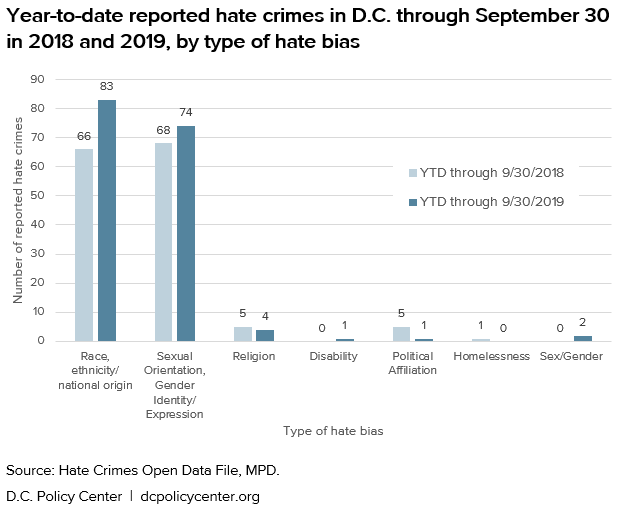

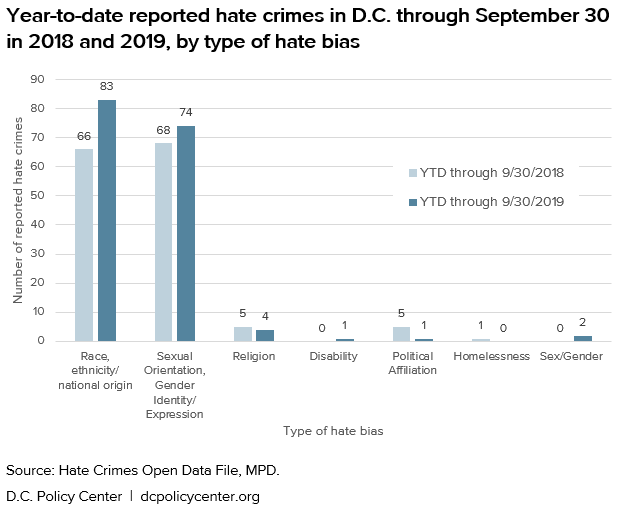

2018 was a record setting year for hate crimes in the District of Columbia, and the number reported continues to rise this year: 108 hate crimes were reported to the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) during the first half of 2019, 30 percent more than the same period for last year.[1] About half of the reported cases were anti-LGBTQ crimes; most of the remainder were based on victim’s race, ethnicity, or national origin.[2] Across America’s thirty largest cities, the number of hate crimes reported rose nine percent to a decade-high of 2,009 in 2018, according to the Center for the Study of Hate & Extremism (CSHE) at California State University.

Hate crimes are generally understood to be crimes that are motivated—in whole or in part—by bigotry against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity. In D.C., the legal definition under the Bias-Related Crime Act of 1989 is somewhat broader, including “actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital status, personal appearance, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, family responsibility, homelessness, physical disability, matriculation, or political affiliation.” According to MPD, the designation “hate crime” is best understood not as a separate type of crime, but an instance where the motivation of the perpetrator can lead to more severe sentences.[3] For example, offensive or hateful speech itself cannot not considered a hate crime unless it is accompanied by a criminal act, such as a threat, assault, robbery, or property damage (such as vandalism).[4]

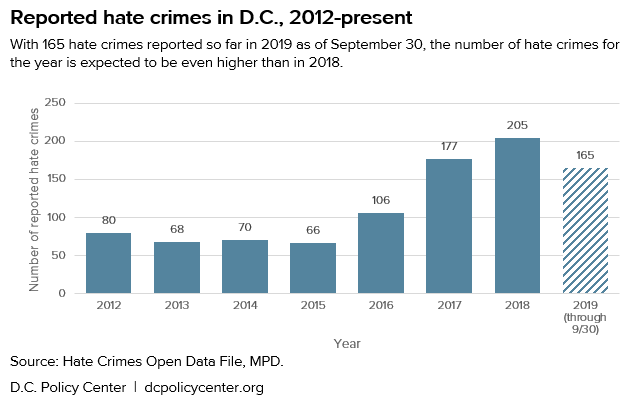

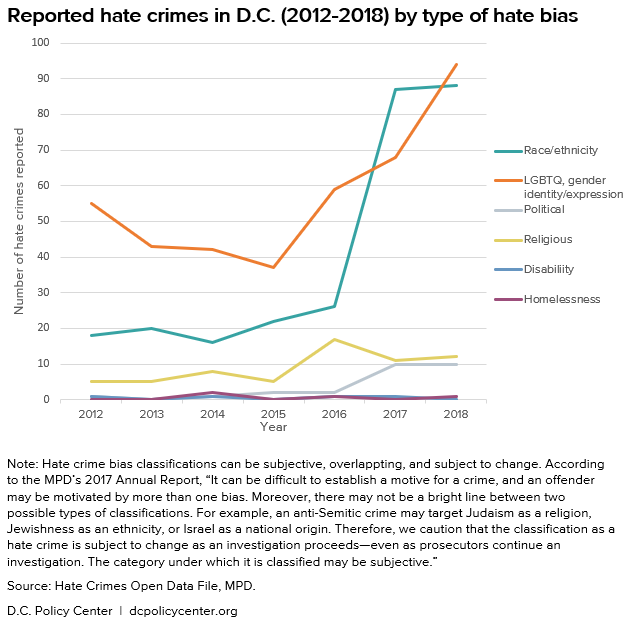

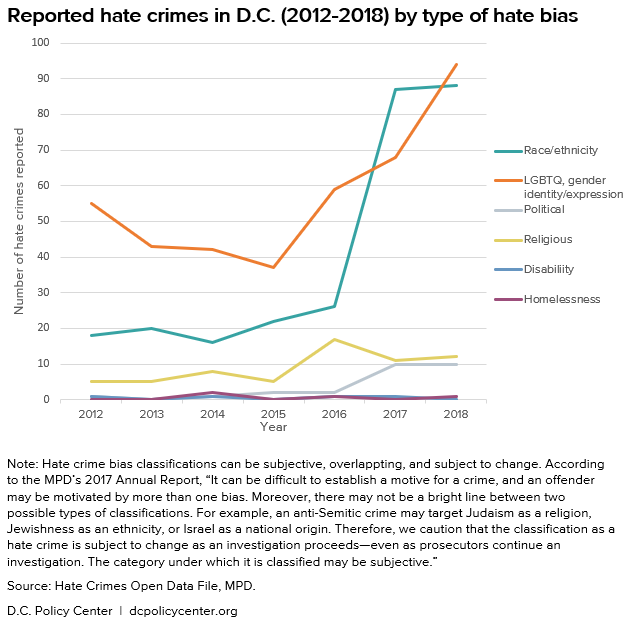

The number of hate crimes reported in D.C. rose sharply in 2016 and continues to climb, as the Washington Post has reported in a series of articles.[5] In 2015, 66 hate crimes were reported; in 2016, that number was 106. By 2018, that number had almost doubled, reaching 205—and 2019 is on track to be even higher. The District of Columbia is among the cities with the highest per capita number of FBI submitted hate crime reports.

Hate crimes have been increasing across the country, including hate crimes motivated by bias against gender identity.[6] Disparities between the National Criminal Victimization Survey (NCVS), conducted by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, and the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program, which gathers voluntarily submitted statistics from law enforcement agencies, also suggest that hate crimes remain under-reported.[7] (According to the NCVS, between 2011 and 2015, 54 percent of hate crimes were not reported to police.)[8]

The rise in reported hate crimes could also be a partial reflection of better practices by law enforcement in reporting and responding to these crimes; according to the Metropolitan Police Department’s most recent Annual Report, several MPD units—including the Criminal Investigation Division, the Strategic Change Division, the Intelligence Branch, and the Special Liaison Branch[9]—work together to respond to, investigate, and classify hate crimes.

Over 200 hate crimes were reported to MPD in 2018, leading to 59 arrests. According to the Washington Post, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia (a federal position in the U.S. Department of Justice that prosecutes most of D.C.’s criminal cases) “prosecuted only three as hate crimes, and one was quickly dropped.” And not a single offender has been convicted. In contrast, the Washington Post reports that other large cities experiencing rising hate crimes, such as Los Angeles and Seattle, have kept up hate crime prosecutions alongside hate crime arrests.

How the types of reported hate crimes have changed over time

The stark rises in reported hate crimes in D.C. seen in the last several years have been primarily driven by a rapid increase in the number of crimes reported against LGBTQ groups and communities of color, most noticeably since 2015 (Figure 1). Anti-LGBTQ crimes and race-based hate crimes now make up more than two-thirds of all hate crimes reported in the District of Columbia. Other types of hate crimes include those against political affiliation and religion and disability.[10]

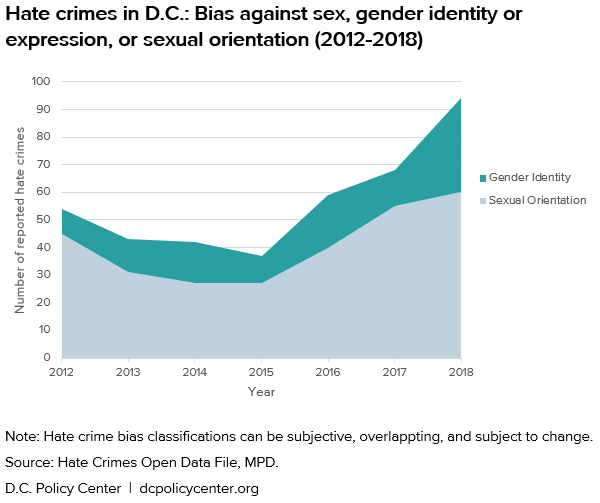

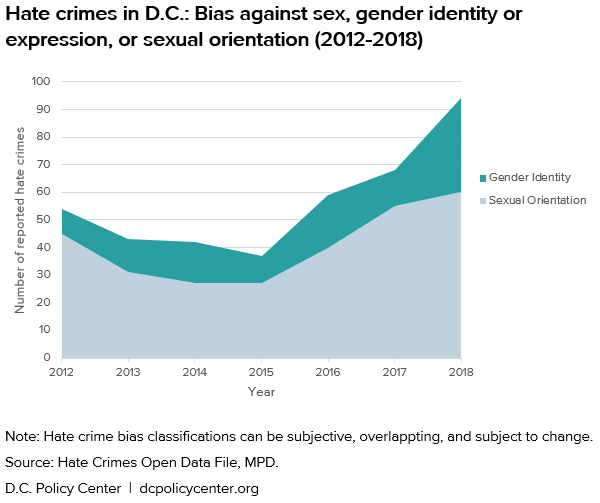

Anti-LGBTQ crimes include crimes motivated by hate-bias against sex, gender identity or expression, and sexual orientation. Accounting for nearly half of all hate crimes reported in 2018, the majority of these crimes involved assaults—including assaults with dangerous weapons—followed by threats, robberies, and property damage. A large share of anti-LGBTQ crimes continues to be motivated hate-bias against victim’s sexual orientation, but hate crimes motivated by bias against gender identity or expression are also becoming more common.

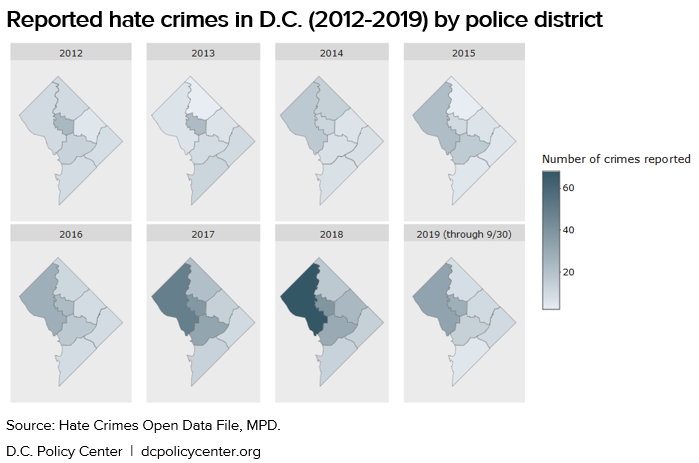

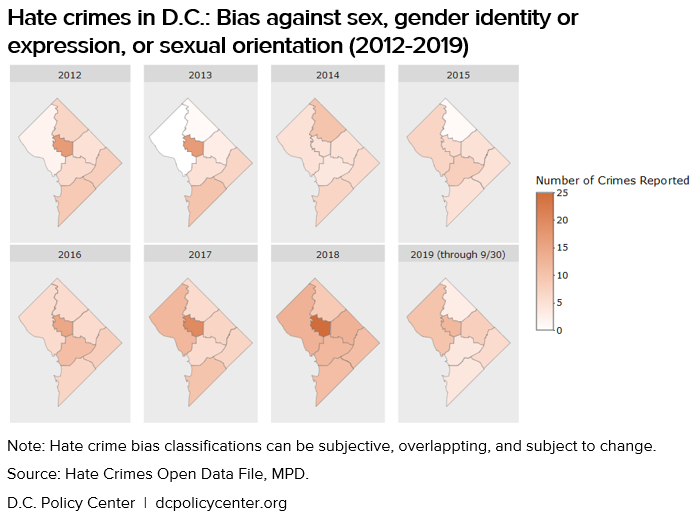

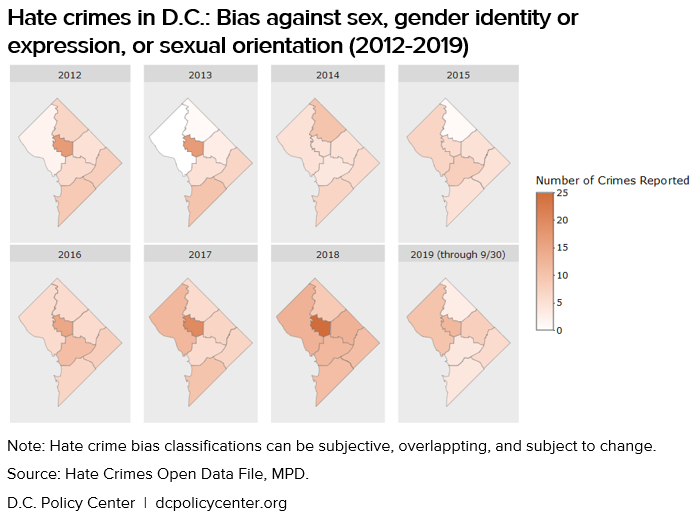

Anti-LGBTQ crimes were most frequently reported in District 3 in 2018, followed by districts 2, 5, and 1. According to the Washington Post, the large share of hate crimes in this category could be related to the relative size of D.C.’s LGBTQ community, which accounts for roughly 10 percent of D.C. residents, and MPD attributes some of the rise in reported crimes to “better reporting and closer relations between law enforcement and gay and transgender residents.”

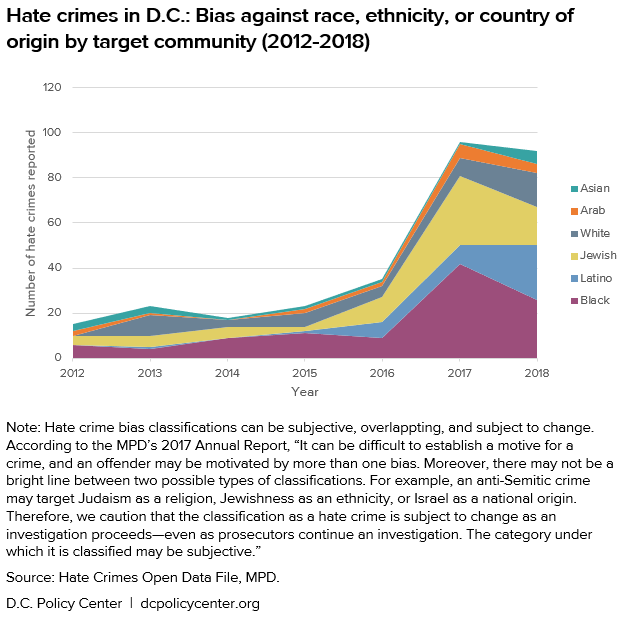

Closely trailing anti-LGBTQ crimes were hate crimes based on racial, ethnic, and national origin bias. In 2018, 88 hate crimes based on race/ethnicity/national origin were reported, up from 22 in 2015. A majority of hate crimes motivated by bias against race, ethnicity, or national origin targeted the District’s Black and Latinx residents, followed by Jewish and white residents.

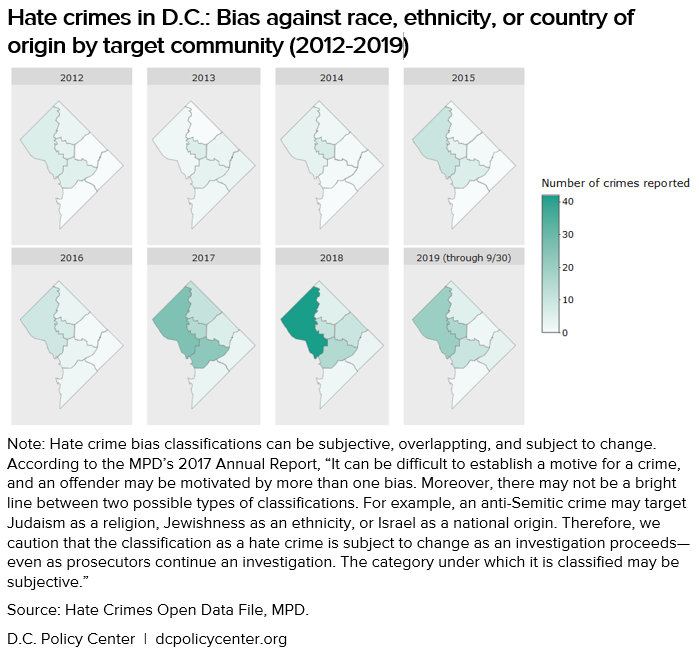

In 2018, a total of 88 hate crimes reported in D.C. were motivated by hate bias against victim’s race, ethnicity, or national origin. More than half of these crimes targeted the District’s Black and Latinx communities, while the rest targeted Jewish, white, Asian and Middle Eastern residents. Hate crimes against race, ethnicity, or national origin are most frequently reported in districts 1, 2, and 3, with districts 6 and 7 are least likely to report these crimes.

Bringing a public health lens to addressing the effects of hate crimes

Approaching hate crimes strictly from a law enforcement perspective may not be enough to understand and address these crimes’ broader impact on targeted communities. Instead, we need a more holistic approach that rests at the intersection of public safety and public health, while being aware of the race and gender dimensions of violence motivated by bigotry.

In 2017, the American College of Physicians officially recognized hate crimes as a public health issue, calling attention to the profound role of hate in undermining individual and community health. The American Academy of Family Physicians acknowledges that hate crime pose “specific and distinct health risks” for patients, and the American Medical Association has for years had a policy recognizing that hate crimes pose a “significant threat” to public health.

A growing body of evidence also sheds light on the profound role of hate violence in undermining individual and community health. Hate crime survivors are more likely to experience psychological distress compared to survivors of other violent crimes. The health of the community, in particular the targeted groups, also suffer as the underlying threat of hate violence increases.

Women of color, especially women of color who identify as LGBTQ, are most frequently targeted by hate crime offenders. Across the U.S., at least 22 transgender people have been killed this year [updated as of November 18, 2019], almost all Black women. In fact, Black transgender women experience the highest levels of violent crimes within the LGBTQ community, the Human Rights Campaign reports, and are less likely to trust the police for help for fear of revictimization by law enforcement.

Similar to systematic discrimination, hate crimes affect individuals and communities simultaneously along multiple dimensions—race, sex, ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, and so on. Across the country and in D.C., hate crimes primarily target Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ communities—groups already marginalized and discriminated against in housing and employment.

Individuals and communities targeted by hate crimes are forced to experience not only trauma from the crimes themselves, but also the underlying threat of that violence, which takes a further toll on the health of the community. A 2014 study in Boston found that LGBTQ youth in neighborhoods with higher rate of anti-LGBTQ crimes were more likely to experience suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Black communities, who have an extensive history of discrimination, abuse, and segregation, face a 9.1 percent rate for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), compared to 6.8 percent of white residents.

In D.C., nearly 12 percent of Black adults reported experiencing poor mental health for more than 2 weeks, compared to 6.8 percent of white adults. LGBTQ adults—who account for more than 10 percent of D.C. adults—are also more likely than their non-LGBTQ counterparts to report long periods of poor mental health. LGBTQ youth in the city do not fare well either. High schools across the District—where LGBTQ students account for 12 percent of the student population—are also seeing an increasing percentage of LGBTQ youth facing threats and assaults due to hate bias.

D.C. needs a community-based public health framework that coordinates with law enforcement and public education, while fully taking into account the intersections between gender, race, and health, education, and socioeconomic outcomes, and profound role of discrimination and hate crimes in those outcomes. This would require an improved infrastructure for information exchange between healthcare, law enforcement and the community. In addition to tracking fatal injuries and homicides as social determinants of health, systematic discrimination and hate crimes should also be tracked and monitored, with a particular attention to marginalized communities, including women of color and LGBTQ people of color. In addition to engaging community advocates and local law enforcement, the District’s healthcare system should also educate the public about the harmful effects of hate crimes and discrimination on the public’s health.

Finally, improved access to affordable mental health services would help not only targeted individuals and communities, but also the public. Therapy and counseling in D.C., like the rest of the country, continues to be treated as a healthcare privilege rather than a need. However, if we want to adequately respond to the alarming hate crimes in D.C., affordable mental health care and counseling are not only a necessity for individuals and communities targeted by hate crimes, but also potential offenders of hate crimes.

About the data

Data on hate crimes in D.C. is from the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). Up-to-date data tables and annual reports on bias-related crimes are available at https://mpdc.dc.gov/hatecrimes. The Hate Crimes Open Data File, with more detailed incident-level data from 2012 through June 30, 2019 as of the time of publication, is available here. (The hate crimes tracking spreadsheet is not an official MPD database of record and may not match details in records pulled from the official Records Management System.)

The data reported by MPD comply with D.C. Official Code § 22-3700. According to MPD, because the D.C. statute differs from the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting definitions, and includes categories not included in the FBI definitions, these figures may be higher than those reported to the FBI. All figures are subject to change if new information is revealed during the course of an investigation or prosecution.

Feature photo by Ted Eytan (Source)

D.C. Policy Center Fellow Shirin Arslan is an economist who specializes in gender analysis in economics and workers’ economic security. She holds a master’s degree in economics from American University and B.A. in Economics from Virginia Commonwealth University. Learn more about her work at shirinarslan.com.

Notes

[1] YTD 2018 through June 30, 2018 was 83; YTD 2019 through June 30, 2019 was 108. Source: MPD. (Numbers have since been updated.)

[2] All but 3 of the 108 reported hate crimes during January 1 – June 30, 2019 were race or gender-based hate crimes. Race-bias crimes (58) include bias against victims Ethnicity or National Origin (34), Race (24); anti-LGBTQ crimes (47) include those driven by bias against gender identity (12), sex or gender (2), and sexual orientation (33). See https://mpdc.dc.gov/hatecrimes

[3] Enacted in 1989, the District’s Bias-Related Crime Act allows judges to enhance sentences for the underlying crime by up to 1½ times the maximum fine and imprisonment if the crime was committed based on victim’s race, religion, age, ethnicity or national origin, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, homelessness, or political affiliation, among other categories.

[4] According to the MPD’s 2017 Annual Report, “It is important for the community to understand what is – and is not – a hate crime. First and foremost, the incident must be a crime. Although that may seem obvious, most speech is not a hate crime, regardless of how offensive it may be. In addition, a hate crime is not really a specific crime; it is a designation that makes available to the court an enhanced penalty. In short, under the law, there is no specific hate crime but rather a crime motivated in whole or in part by bias.”

[5] See: He always hated women. Then he decided to kill them.; A black principal, four white teens and the ‘senior prank’ that became a hate crime; D.C. hate crimes: Inside a record year of hatred in the nation’s capital; Hate crime reports have soared in D.C. Prosecutions have plummeted.

[6] See also Violence Against the Transgender Community in 2019, Human Rights Campaign.

[7] 2018 NCVRW Resource Guide: Hate Crime Fact Sheet. Office for Victims of Crime, U.S. Department of Justice.

[8] Madeline Masucci and Lynn Langton, Hate Crime Victimization, 2004-2015. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice. Cited in the 2018 NCVRW Resource Guide: Hate Crime Fact Sheet.

[9] Established in 1998, the Special Liaison Branch (SLB) works with hate crime victims, communities to lead MPD’s efforts to combat hate crimes. The SLB is composed of the Asian Liaison Unit (ALU), Deaf and Hard of Hearing Liaison Unit (DHHLU), Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Liaison Unit (LGBTLU), and the Latino Liaison Unit (LLU). In addition to training MPD officers and coordinating with various MPD divisions to respond to hate crimes, The Branch also leads outreach activities to strengthen ties with communities targeted by hate crimes. It holds monthly meetings with LGBTQ community advocates, speaks regularly on Latinx radio stations, and hosts presentations and discussions on tolerance and safety.

[10] An important consideration for this data is that it does not account for multiple or intersecting motivations for a hate crime, and a hate crime might be classified in different ways depending on the details of the case. According to the MPD’s 2017 Annual Report, “It can be difficult to establish a motive for a crime, and an offender may be motivated by more than one bias. Moreover, there may not be a bright line between two possible types of classifications. For example, an anti-Semitic crime may target Judaism as a religion, Jewishness as an ethnicity, or Israel as a national origin. Therefore, we caution that the classification as a hate crime is subject to change as an investigation proceeds—even as prosecutors continue an investigation. The category under which it is classified may be subjective.”