Why does the city that’s frequently ranked the “Healthiest City in America” still have such disparities in health outcomes for its African American residents?

When talking about health disparities in the District, the narrative is usually the same: African American residents in Wards 7 and 8 are either at risk or are greatly impacted by illnesses such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, kidney disease and cases of sexually transmitted diseases. These disparities are so well-known, they aren’t even newsworthy any more; it’s almost as if we can no longer see them.

To be sure, there are bright spots. The District seems to be on the right track to address many of these health disparities, especially east of the river:

- More than 96 percent of District residents are insured thanks to the Affordable Care Act, which cut D.C.’s uninsured rate—already low thanks to the D.C. Healthcare Alliance—in half.

- With the opening of the Benning Ridge DMV Service Center in Ward 7, the Department of Motor Vehicles partnered with the Department of Health to offer onsite HIV screenings for those receiving DMV services.

- A newly released report shows that Wards 7 and 8 experienced a drop in the teen birth rate since 2010, with Ward 8 showing the most notable decrease (37 percent). While teen birth rates have been dropping nationwide, the District has also put in $1 million in consistent funding towards teen pregnancy prevention programs and for peer sex educators.

- Along with providing funding for Produce Plus, a program that provides access to locally grown fruit and vegetables for families receiving Medicaid, TANF, Social Security, or SNAP benefits, the District has also latched onto urban farming.

- Non-profit organizations are also contributing, with one that has launched a citywide campaign addressing kidney health, with a focus on communities east of the river.

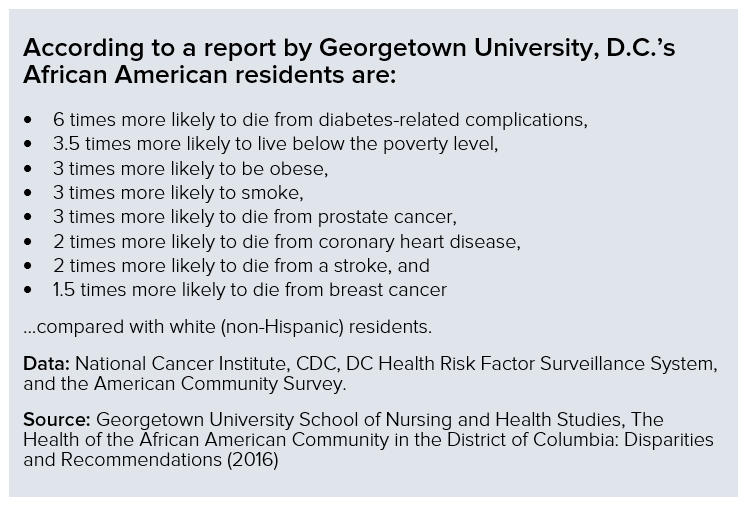

But even with these advances, a report by Georgetown University on health disparities in the District found that African American residents are still being left behind. For instance, African American residents are six times more likely than white residents to die from diabetes-related complications, and twice as likely to die from coronary heart disease. Despite D.C.’s rapid economic growth and increasing prosperity, “health outcomes and quality of life indicators for African American residents do not reflect trends of the general population,” the report finds.

Source: Georgetown University

So why does the same city that’s frequently ranked the “Healthiest City in America” still have such disparities in health outcomes for its African American residents? The answer is complicated, encompassing gentrification and demographic change, broken trust between the community and health care providers, and complacent attitudes about investments in the community.

Gentrification and displacement mask persistent disparities

One of the challenges in addressing health disparities between African Americans and other District residents is how gentrification and displacement are changing the geography of the city.

According the Georgetown report, D.C.’s African American population has dropped by 20 percent over the last three decades, as families and individuals migrate to locations with affordable housing options.

The impact on health disparities is twofold. First, for existing, long-time residents, high housing costs and housing instability can lead to a host of other health risk factors, ranging from homelessness and food insecurity to job loss and social isolation. As a result, “chronic or survival stress associated with meeting day-to-day needs increase [these residents’] risk for chronic disease conditions and mental dysfunction.”

Second, demographic change and displacement can obscure where disparities still exist, thereby making it more difficult to address them. One example of this is teen birth rates: As mentioned earlier, Wards 7 and 8 both experienced a drop in the teen birth rate since 2010, including a decrease of 37 percent in Ward 8. However, as George Washington University professor Antwan Jones notes, as low-income residents are forced out of the District by high housing prices and other pressures, they often move into similarly distressed neighborhoods in Maryland or Virginia—which can then see increases in teen births. D.C.’s declining teen birth rates, in other words, likely reflect changes in who lives in the District, rather than actual improvements for the individuals in question.

Building trust in the health care system

Another challenge that is often overlooked is African Americans’ historically complex relationship with the health care system. Many still feel an underlying mistrust in a system that has often treated African Americans as experimental guinea pigs, or that has not extended the same quality of care as our counterparts—think the Tuskegee Syphilis experiment, or even the story of Henrietta Lacks.

“Given what generations of African Americans have experienced, it is irrational to think African Americans should not have a level of distrust when it comes to health care,” says Dr. Thomas LaVeist, Chair of George Washington University’s Department of Health Policy and Management.

Dr. LaVeist has studied and written several reports examining minority populations, particularly African Americans, and health disparities. He asserts that with the “trust factor” as a foundation, complacent attitudes towards the need for quality health care have done more harm.

“We have fallen into a traditional pattern. We say ‘black don’t crack,’ and we subscribe to the belief that we don’t. We are cracking, especially in terms of mental health. We have this cultural Christianity, where we turn to our places of worship to treat our mental health,” says Dr. LaVeist, who mentions as an example, the latest incident with Steve Stephens, an African American male suffering from mental health issues who randomly killed an elderly man in Cleveland on Easter Sunday.

Closing the gap requires a far-reaching approach

Years of neglecting or improperly addressing the health needs of African Americans have led us to normalize the disparities. How do we begin to change the narrative when it comes to advocating for health care needs? Dr. LaVeist suggests that it is all in the form of nuanced communication between the major health advocacy organizations, the government, and the community.

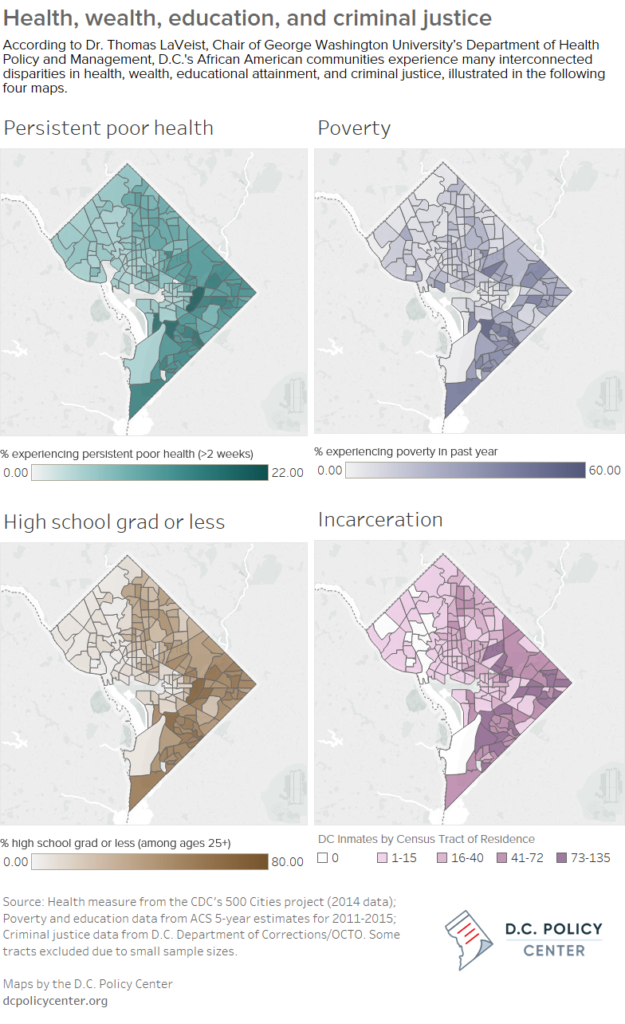

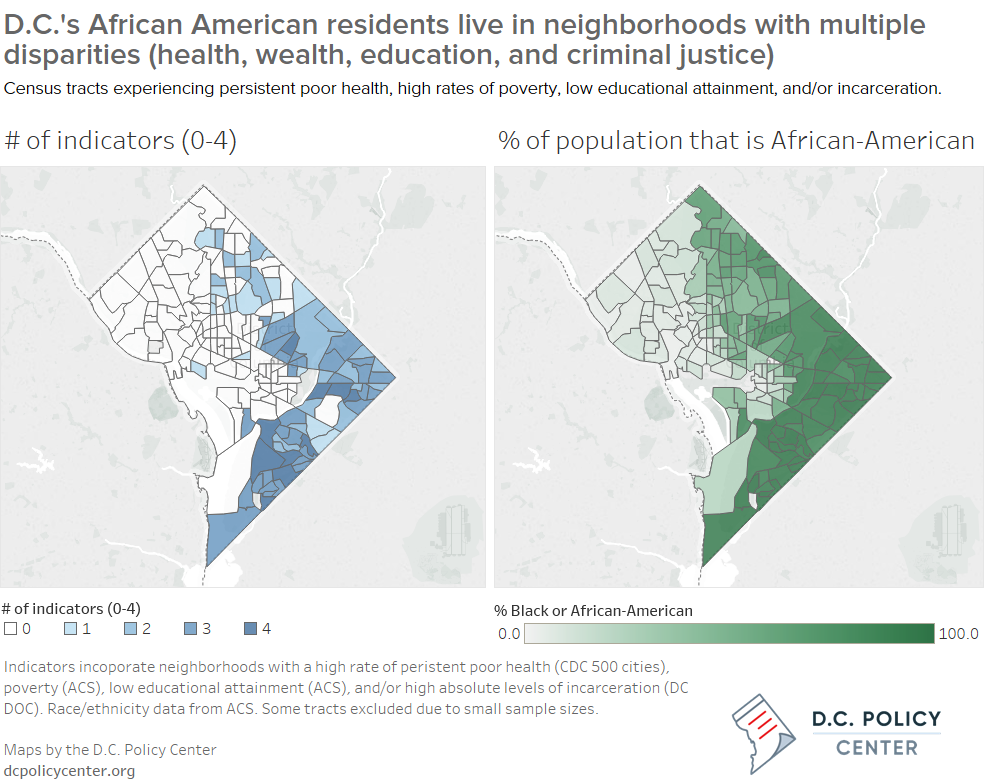

“There are four disparities that affect the African American community. They are wealth, education attainment, criminal justice and health. We have to understand and learn how to communicate that the four of these are connected,” says Dr. LaVeist.

Click here to explore an interactive version of the above map.

Click here to explore an interactive version of the above map.

Dr. LaVeist’s thoughts echo the recommendations from the Georgetown report. The report concludes that in order for the health of African American residents in the District to improve “it requires an explicit and cross-sectorial agenda to eliminate social, economic and environmental conditions.” Unless the District engages the underlying issues at play, the report says, the actual impact of its attempts to streamline healthcare delivery for African American residents may be “marginal.”

Dr. LaVeist also suggests that more resources could be invested and used to support existing community advocacy groups.

Currently Mayor Bowser is proposing more than $200 million for the Department of Health (DOH) for the fiscal year 2018. Of that, the Mayor boasts $0.9 million will be used to curb opioid use with the goal of reducing overdoses and overdose fatalities. More than $73,000 is proposed for the Community Health Administration (CHA) within DOH. CHA addresses access to health care, promotes cancer and chronic disease prevention, nutrition and physical fitness, perinatal and infant health and family health. Along with investments for DOH and its programs, the Mayor is proposing nearly $300 million for the Department of Behavioral Health.

Legislation has also been introduced for a new hospital that would serve Wards 7 and 8. The bill calls for the construction of a new hospital to be built on the campus of St. Elizabeth’s. It also proposes the creation of a special fund for the construction of the hospital as well as establishes a grocery and retail incentive program. Currently United Medical Center (UMC), which borders Ward 8 and Prince George’s County, MD, services residents east of the river. Though it has faced financial and management challenges, UMC has been making progress in becoming a self-sufficient entity. Still, it is missing a trauma center, which has become a selling point for the proposed legislation, along with turning UMC’s current location into fertile ground for an affordable retail complex.

While there are groups in the African American community that are pushing for various health policies, more engagement is needed, as the stakes are high when it comes to African Americans and our health. It is encouraging to see residents across the city become actively involved in advocating for the health needs of all. However, it is concerning that in Wards 7 and 8, where the disparities are most keenly felt, that involvement usually includes only the same faithful few community leaders. We need to engage, on a consistent basis, the families in Benning Heights, Knox Hill, Bellevue, Lincoln Heights, Fairlawn, and beyond.

Though the District seems to be on the right course in addressing health disparities in the African American community, true impact will require a cohesive effort that includes a wide range of stakeholders—from community members to government officials to location and national health advocates—to communicate how health is interconnected with education, public safety, and socioeconomic factors.

About the data

The maps for this post were created by the D.C. Policy Center. Data for the maps were drawn from the following sources:

- Health: Percentage of residents in each census tract who experienced poor health lasting at least 2 weeks: CDC’s 500 Cities Project (variable: phlth_crudeprev)

- Wealth/poverty: Percentage of residents in each census tract who experienced poverty in the past year: ACS 5-year estimates for 2011-2015.

- Education: Percentage of residents in each census tract whose educational attainment is a high school degree or less (for adults 25 and older): ACS 5-year estimates for 2011-2015.

- Criminal justice: Number of DC inmates by census tract of residence: DC Department of Corrections (July 2014 – December 2015).

- Race/ethnicity: Percentage of black or African American residents in each census tract: ACS 5-year estimates for 2011-2015.

Census tracts were excluded from the analysis if they contained fewer than 500 people or households, depending on the unit of measurement. These tracts are not present in the relevant maps, and were not included in indicator count calculations.

The indicator count that showed the overlapping of health, wealth, education, and criminal justice-related factors was created as a general impression of challenges facing D.C. communities:

- Health: A census tract received a 1 if the proportion of residents experiencing persistent poor health was >11 percent.

- Wealth/poverty: A census tract received a 1 if the proportion of residents who experienced poverty in the past year was > 30 percent.

- Education: A census tract received a 1 if the proportion of residents age 25 and older who had at most a high school degree (or less) was greater than 40 percent.

- Criminal justice: A census tract received a 1 if the number of DC inmates from that location was 73 or greater (max: 135).