High school students in D.C. have been especially impacted by the pandemic. In an EmpowerK12 survey of 2,500 public charter school students, high schoolers’ responses indicated that they were the least confident in their ability to succeed during distance learning compared to students in other grade bands.[i]

Although some have thrived in a virtual environment, many of the high school students who participated in a November 2020 D.C. Policy Center focus group described experiencing a range of challenges associated with distance learning such as lack of motivation, difficulty managing distractions at home, or lack of structure. They also thought the pandemic would have a negative impact on their futures, especially as they begin transitioning to college or to a job after high school.[ii] High school students have the least time left in D.C.’s schools compared to students in other grades to take advantage of any academic supports, and some are already transitioning to postsecondary or the workforce. This briefing takes stock of how the pandemic may have affected high school students and highlights its impact on students designated as at-risk[iii].

High school enrollment

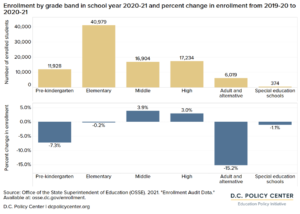

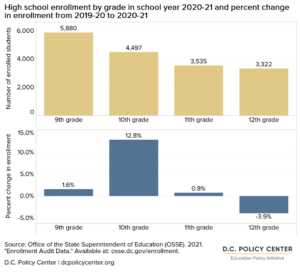

When school year 2019-20 began, there were 34 high schools in D.C., including 17 D.C. Public Schools (DCPS) and 17 public charter schools, serving 16,738 high school students. From school year 2019-20 to school year 2020-21, enrollment in the city’s public schools decreased from 94,412 to 93,438, falling by 974 students on net, indicating that many have disengaged, transitioned to homeschooling, or left for other states, private schools, or childcare centers. While enrollment fell most dramatically in non-compulsory grades (about 1,000 fewer students each in pre-kindergarten and adult or alternative schools), enrollment in high school grades increased by 496 students. High school enrollment increased most among grade 10 students. Enrollment in grade 12, on the other hand, fell by 134 students.

The overall increase in high school enrollment occurred just as promotion guidelines that determine which students move on to the next grade were relaxed to accommodate students struggling to participate in school during the pandemic. To be promoted in a normal year, high school students enrolled in DCPS had to participate in 120 hours of instructional time per class each year. They also had to have fewer than 30 unexcused absences.[iv] Shortly after the District transitioned to distance learning, DCPS (serving 62 percent of high schoolers in school year 2019-20) implemented a more lenient policy in which a student could not be held back unless the family and school agreed that retention would be in the student’s best interest. Charter Local Education Agencies (LEAs) implemented similarly relaxed guidelines regarding promotion.[v] For example, KIPP DC, which teaches more high school students than any other charter LEA, normally required students to earn a certain number of credits to be promoted.[vi] Due to the pandemic, it began to only consider retaining students if they had missed a significant number of school days prior to March 16, 2020 and had not demonstrated adequate academic progress prior to March 16, 2020.[vii]

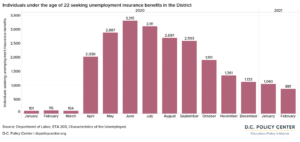

The increase in overall high school enrollment could also be attributed to fewer employment opportunities for youth during the pandemic. In April 2020, 2,030 workers under the age of 22 received unemployment benefits, a 19-fold increase compared to March 2020, indicating that many workers under the age of 22 lost their jobs at the onset of the pandemic and were unable to find new jobs. This data suggest that students who might have considered leaving school to join the workforce would have been unable to find jobs.

“When the public health emergency began in March, I was laid off. Since then, I’ve been applying to all sorts of jobs, and the process has been frustrating. Last month, I applied to 35 jobs and only received two calls.” – High school senior, 2019-20

High school graduation

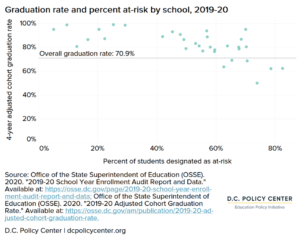

Between school years 2018-19 and 2019-20, the overall graduation rate increased from 68.2 percent to 70.9 percent, reversing a downward trend. The overall graduation rate also exceeded the District’s 2020 goal of a 70.5 percent graduation rate.[viii]

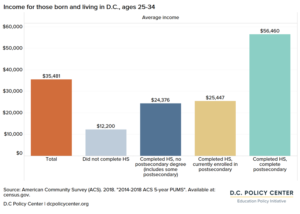

Graduating from high school can unlock higher-paying career opportunities and allow access to postsecondary institutions. Census data show that 25- to 34-year-olds born and living in D.C. without a high school diploma earn an average of $12,200 while those who completed high school earn an average of $24,376. Those with postsecondary degrees earn even more with an average annual income of $56,460.

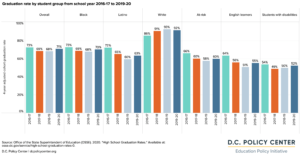

Gaps in graduation rates for different student groups decreased slightly in school year 2019-20, as every student group except white students experienced gains of between two to four percentage points. However, all student groups except white students had graduation rates that were lower than they were four years ago. Students designated as at-risk exhibited a graduation rate of 60 percent in school year 2019-20. This is four points higher than in 2018-19 but down from 66 percent in 2016-17. The graduation rate for at-risk students is also 11 percentage points lower than the overall graduation rate.

Similar to increased enrollment, the rise in graduation rates in school year 2019-20 could be due in part to relaxed graduation requirements necessitated by the pandemic. In a normal year, D.C. regulations mandate that prospective graduates must participate in 120 hours of classroom instruction time during each academic year in required courses. They must also complete 100 hours of community service. Given the challenges associated with participating in virtual instruction and social distancing guidelines that made it difficult to volunteer in-person, OSSE waived the classroom instruction requirement for any courses in which high school students were enrolled during distance learning and waived the requirement for 100 hours of community service.[ix]

“The greatest challenge we’re facing is the social loss. My daughter is a senior, so she’s not going to be able to participate in events like prom or graduation. She’s an only child, so I was really looking forward to these milestones. Her school has said they’ll organize a prom and an in-person graduation at some point, but it’s hard to not know when that will be possible.” – Parent

“This situation is really tough for me. It’s my senior year, and we were just getting to that point in the year where it starts to actually feel like senior year. People are about to get accepted to college, I was supposed to start flag football. Now, I don’t know if we’ll be able to say goodbye to our teachers, I don’t know if we’ll have a yearbook. Some people might think this is trivial, but I really wanted these memories to look back on one day.” – High school senior, 2019-20

Despite relaxed graduation requirements, prospective graduates who were designated as at-risk still faced many obstacles and were more likely to be impacted by the health and economic consequences of the pandemic. 59 percent of at-risk students live in Wards 7 and 8, where residents make up 22 percent of the population but account for 28 percent of COVID-19 cases and 35 percent of lives lost as of February 2021. Communities in Wards 7 and 8 also have less local access to healthcare clinicians and pharmacies, the lowest median household incomes in the District, and the highest unemployment rates. Students also had less access to high speed internet and devices than students in other wards. When virtual instruction began, 24 percent of children in D.C. lacked access to broadband internet, but this share was greater in Wards 7 and 8, where 37 percent of children lacked access.

Graduation rates tended to be lower than the city average at high schools with a higher percentage of students designated at-risk. 14 of the 20 majority at-risk schools had graduation rates that were higher than the overall graduation rate of 71 percent and the remaining 6 majority at-risk schools had the lowest graduation rates in the District.

Postsecondary enrollment

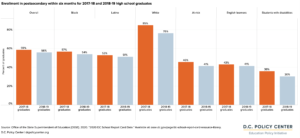

The most recent year of reported data show that 56 percent of all high school graduates in 2018-19 continued to postsecondary education within six months of their graduation, as compared to 59 percent in 2017-18.[x] As of right now, the six-month postsecondary enrollment rate decreased from between two to nine percent across every subgroup. At-risk students, who already had one of the lowest six-month postsecondary enrollment rates, experienced a drop of five percentage points, decreasing from 46 percent to 41 percent. It is too soon to know outcomes for the class of 2019-20 that graduated during the pandemic.

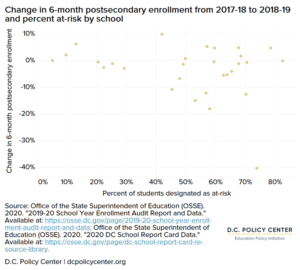

Schools where the majority of students were designated as at-risk experienced the greatest decreases in six-month postsecondary enrollment – one school experienced a drop as large as 40 percentage points. The average decline in post-secondary enrollment at majority at-risk schools was 5.7 percent, while the average decline in other schools was 0.7 percent. It’s likely this trend will continue, as the pandemic forced many graduating seniors – especially those from low-income families – to forego postsecondary education in lieu of finding a job.

FAFSA completion

Analyzing the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) completion rate can reveal how many students are interested in enrolling at a postsecondary institution and thinking about how they might fund their education. Filling out the FAFSA is one of the most important steps a student can take to pay for college. The U.S. Department of Education uses the FAFSA to determine a student’s eligibility for need-based financial aid such as federal grants, scholarships, work-study, and loans.

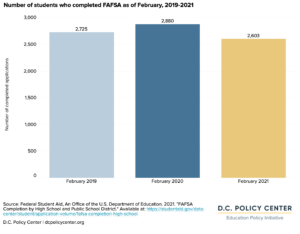

As of February 2019, 78 percent of high school seniors in school year 2018-19 completed the FAFSA form, indicating their interest in attending a postsecondary institution. As of February 2020 – right before D.C. declared a state of emergency – 83 percent of high school seniors filled out the FAFSA form, suggesting that before the pandemic began, more students were considering attending college.

Since then, several factors related to the pandemic have made it more difficult for high school seniors to consider attending a postsecondary institution. School closures and the transition to distance learning necessitated by the pandemic led to increased social isolation and mental health concerns for some and made it more difficult for graduating seniors to speak with their college counselors. These stressors coupled with the economic consequences of the pandemic and the prospect of attending college virtually forced many high school seniors to alter their plans. As of February 2021, 277 fewer FAFSA forms were completed than in the previous year. According to the most recent data available through the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, 29 percent of adults across the country cancelled their plans to take classes at post high school institutions due to the pandemic. Approximately half of those students changed their plans due to changes in financial aid or an inability to pay for classes due to changes in income during the pandemic.

“It’s the plan to go to college after high school. I’m not sure if that will change. I have concerns that I won’t be able to learn over a computer in college.” – High school senior, 2020-21

“I refuse to pay for an online college education unless I’m paying for room and board. I think that’s totally ridiculous. I also feel like trying to apply to colleges will be really weird in the fall.” – High school senior, 2020-21

“We have this class that is dedicated to college and career planning…my friends who take that class say their teacher reminds them of deadlines and keeps them informed about things like the FAFSA.” – High school senior, 2020-21

Conclusion

Many high school students faced unexpected challenges during the pandemic. They struggled to remain engaged in school and may have experienced subsequent learning loss and increased stress and anxiety. Graduating seniors found they had to reevaluate their plans for the future: some decided not to attend college and others who intended to join the workforce may have been unable to find jobs.

As we move into the summer and fall of 2021, the District will offer support for current high school students by way of in-person academic recovery programs and access to mental health care resources in an effort to keep them on track for future graduation. For example, during the summer, DCPS will offer credit recovery and dual enrollment classes.[xi] For current high school students and recent high school graduates, The Marion S. Barry Summer Youth Employment Program (SYEP) will also expand its opportunities. It typically offers paid jobs to 10,000 14-to-24-year-olds, but this summer, it will serve 13,000 participants. It will also offer a new “earn and learn” program that will allow some students to earn money while spending half the day on academics and the other half working.

Graduating from high school and being college or career-ready can eventually lead to a higher income and better quality of life. To ensure that all students can access these opportunities, it will be crucial to assess high school students’ academic and socio-emotional needs in the fall of 2021 and monitor the long-lasting impact of the pandemic on the District’s high school students.