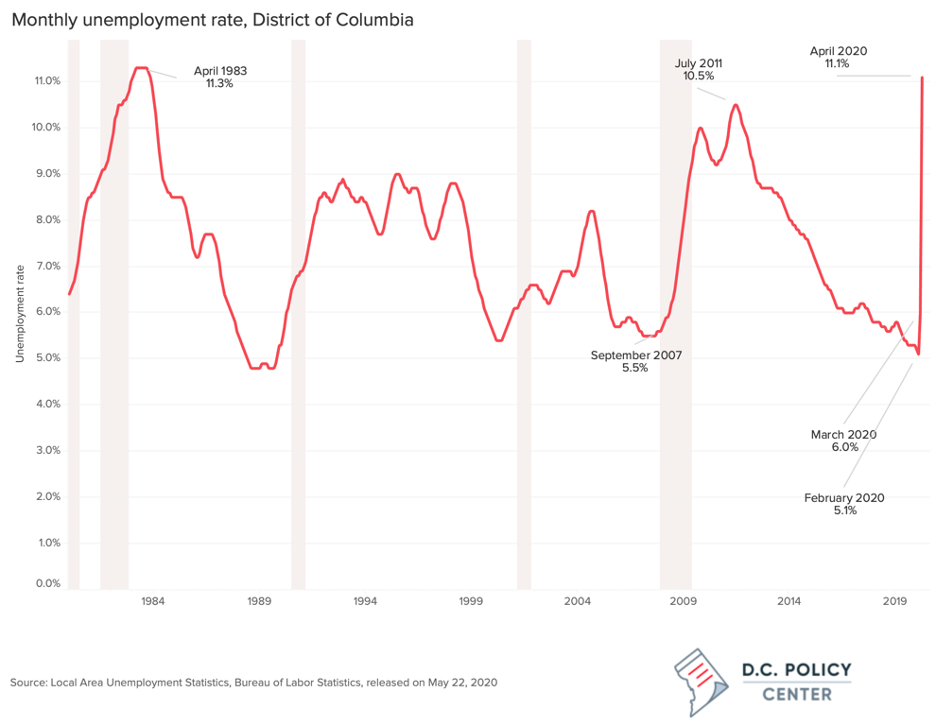

On Friday, May 22, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released its monthly data on employment and unemployment for states and metropolitan areas. These data show that unemployment rate in the District of Columbia now stands at 11.1 percent—the highest rate seen in recent history.

The city reached this level of unemployment with unprecedented speed: the unemployment rate increased by 5.1 percentage points in a single month (from March to April, and by 6 percentage points since February of 2020). To compare, during the Great Recession, the largest continuous increase in unemployment rate was 4.5 percentage points and it took more than two years (specifically 26 months) for the District to experience this. The only other time unemployment rate hit above 11 percent was 1983, after two back-to-back recessions, and it took over three years to get there.

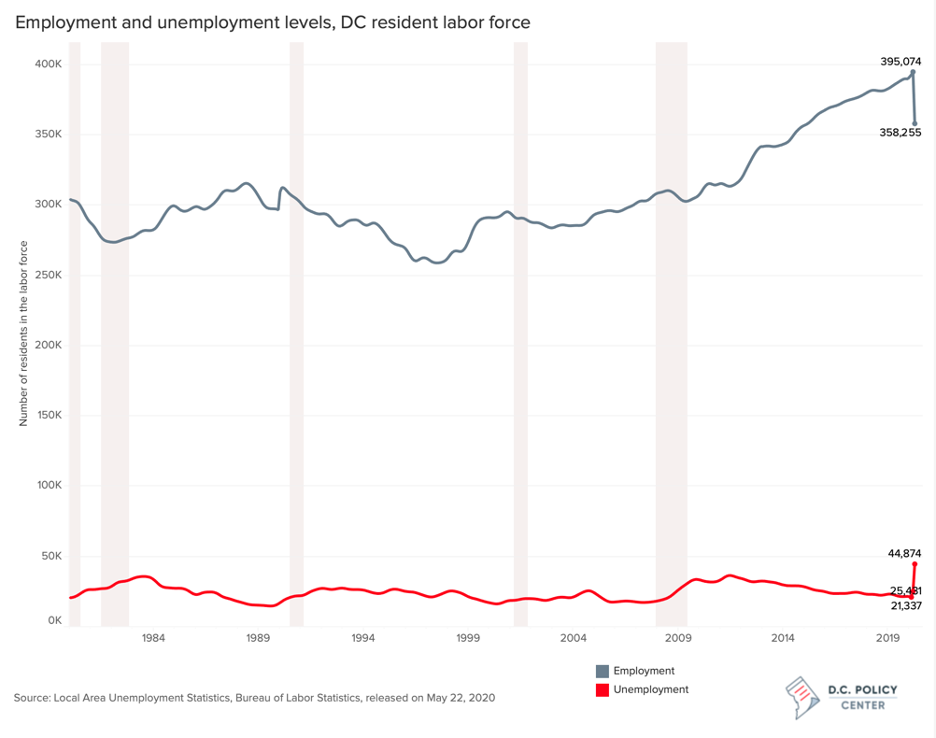

Between March and April, the number of jobs in the District of Columbia declined by 66,900 (or by 8.4 percent). This is only indirectly related to the unemployment rate in the District, since it includes all jobs located in the city, and not just those held by residents. Unemployment is a resident-based measure, which compares the number of D.C. residents who are unemployed (and actively looking for work) to those in the District’s labor force. Between March and April, 36,819 District residents lost their jobs, bringing resident employment figures to 358,255, or back to where they were in March of 2015. The number of unemployed increased, too, but not by that much (by 23,550). This is because not all those who have lost their jobs are looking for a new job and, therefore, are now out of the labor force. According to data from the District Department of Employment Services, the District’s labor force declined by 17,400 between March and April and now stands at 403,100 (same level as March of 2018).

This is, once again, a different picture from what we observed during the Great Recession, when the District’s population and labor force were still growing at a fast pace. During the Great Recession, which began (officially) in December of 2007, resident employment continued its increase through the first half, and then declined during the second half, by about 7,500. But the Great Recession did not discourage workers from moving into the city and looking for jobs: the labor force continued its growth and was larger by 2.3 percent by the end (June of 2009).

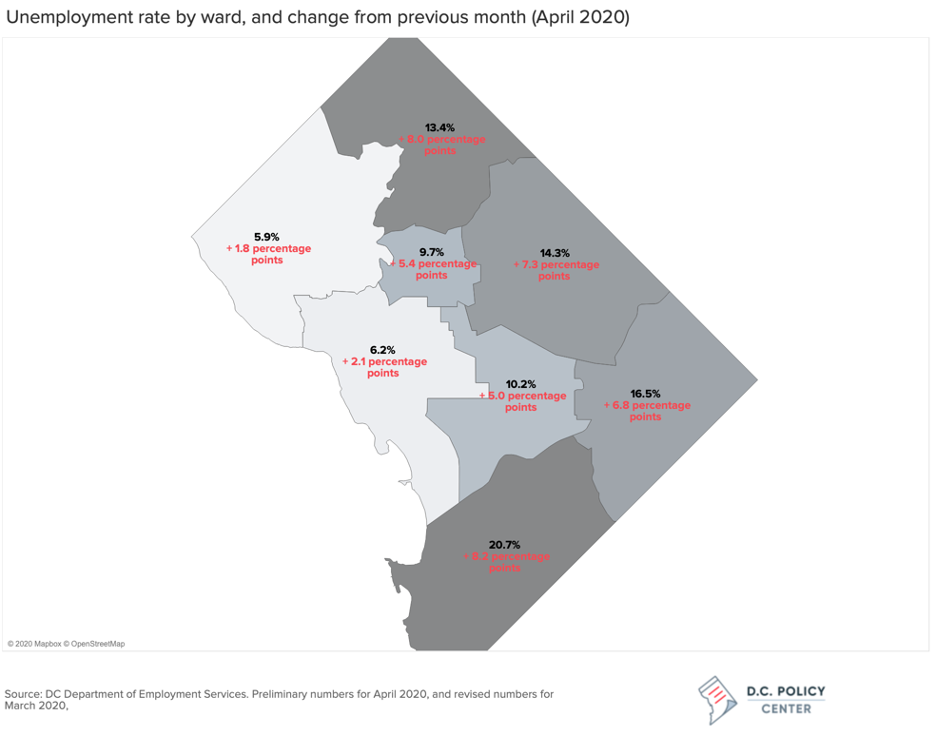

All wards experienced job losses

Preliminary numbers from the Department of Employment Services suggest that no part of the city escaped the economic shock induced by the pandemic, but some wards experienced deeper losses than others. The unemployment rate now stands at 20.7 percent in Ward 8, or 8.2 percentage points higher than where it was in March 2020. Ward 1, which is home to many immigrants, also saw an 8-percentage point increase in its unemployment rate. Five of the eight wards in the city now have an unemployment rate that stands above 10 percent. Wards 2 and 3 have seen the smallest increases in their unemployment rate, but based on the preliminary data, this is not because their job losses were small, but rather because in both wards, more than 80 percent of those who lost their jobs exited the labor force. In contrast, the exit rate from the labor force is 5 percent in Ward 8. Since these are preliminary numbers, they will likely be revised. But if they are correct, they are astounding.

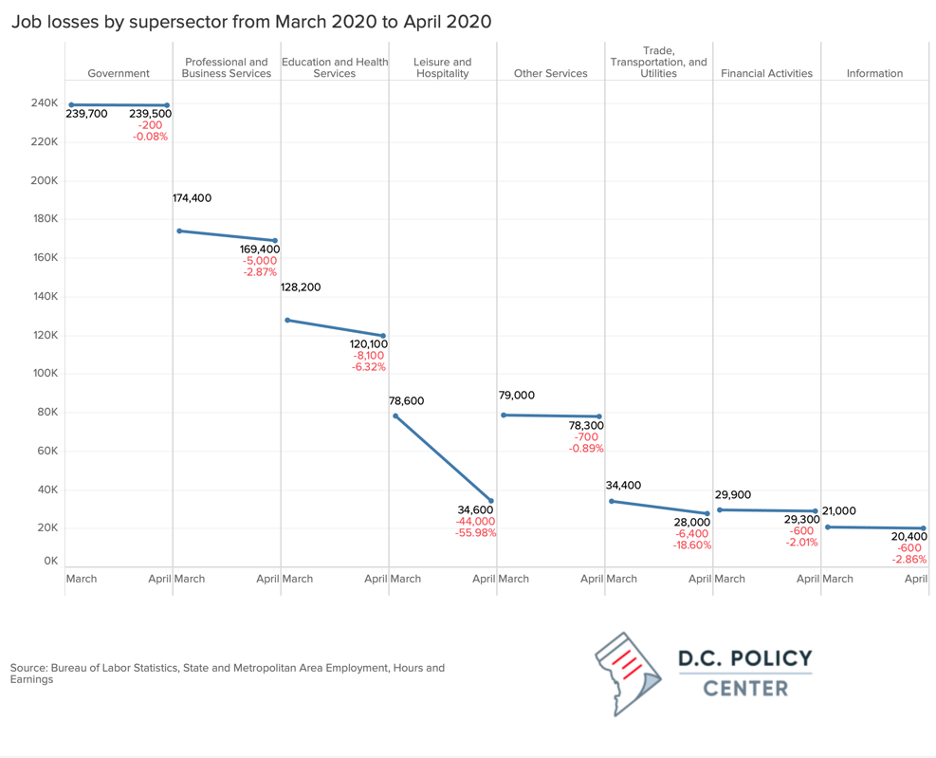

While the hospitality and leisure sector experienced the most devastating losses, the economic impact of the pandemic appears to be spreading.

Almost all the job losses throughout the month of April were in the private sector.[1] While all jobs in the District declined by 8.4 percent from March to April, private sector employment contracted by 11.9 percent. In this single month, the private sector lost the equivalent of eight years of growth, and now stands at 494,800, close to where it was in April 2012.

Between March and April, jobs in the leisure and hospitality sectors declined from 78,600 to 34,600, or by 56 percent. Since 1990, the lowest level of employment in these sectors had been 40,900, recorded in December of 1998. The impacts are deepest for full-service restaurants. In March, full-service restaurants employed 26,700 workers; now they employ 3,300 workers—a decline of 88 percent. Arts and entertainment venues employed over 10,000 workers; more than half lost their jobs from March to April. Hotels employed over 16,000 workers; now they employ 8,800. This more muted response, however, is not an indicator of higher demand for hotels. Most hotels are operating at 10 to 15 percent capacity but have less flexibility in scaling back staff proportionately given their maintenance needs.

The second hardest hit sector is education and health services, which lost 8,100 workers (the equivalent of six years of growth) according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.[2] Job losses in ambulatory services account for over 40 percent of these losses; and hospitals for another third. The education sector held steady according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and experienced smaller losses according to the District’s Department of Employment Services, largely because of cuts made at universities and colleges.

While professional and business services—the bread and butter of the District’s economy—also experienced declines, some sectors within this group continued hiring. Professional, scientific and technical services added over 1,200 jobs, growing at about 1 percent; legal services jobs grew by 1.4 percent, [3] but administrative and support services lost 6,500 jobs and, within this group, employment services lost 4,100 jobs (29 percent decline). [4] Administrative and support services might have a hard time bouncing back even when the pandemic-induced economic shock abates: employment in this sector declined through the Great Recession and failed to make a comeback, holding steady at about 47,500 since 2014.

Employment in retail declined by 5,300 (about 8 years’ worth of loss); and transportation and utilities by 1,000 (lowest level since 1990). Wholesale trade (5,300 employees in the city) and information (20,400 employees) held steady. Under financial activities (29,300 employees), the declines were driven by job losses in real estate and leasing activity while finance and insurance sectors grew. Under other services which includes a combination of personal services, religious organization, grantmaking and civic organizations, including most of the District’s nonprofits, lobbying entities and trade organizations, the losses were largely limited to the nonprofits (and lobbying entities and trade organizations grew by a small amount).

Minorities and young workers experienced more intense losses

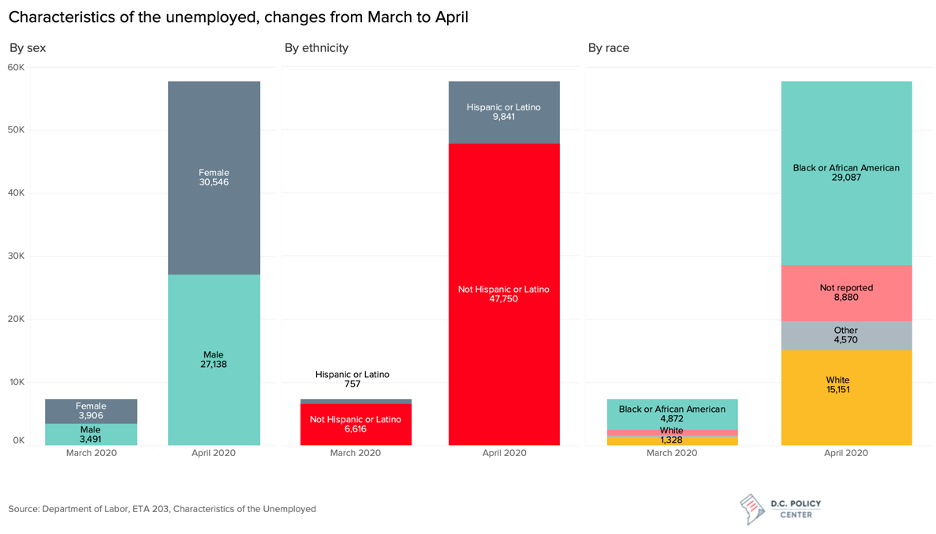

The Department of Labor tracks information on the characteristics of those who are receiving unemployment insurance benefits (called ETA 203, available for download here). Because it is based on recipient information, these characteristics pertain to the District’s entire workforce covered by unemployment insurance including those commuting in from outside the District. This data show that between March and April, the number of unemployment insurance recipients increased from approximately 7,400 to 57,700. To compare, the number of claimants in each month did not exceed 16,500 throughout the Great Recession.

According to this data, more women experienced job losses during the month of April than men. Since the end of the Great Recession, women have made up a larger share of unemployment benefits recipients (but not a larger share of workforce),[5] and this trend continued with the pandemic-induced unemployment. While more women started receiving unemployment benefits than men in April, growth in the number of claimants from March to April were similar: both groups experienced a 6.8-fold growth.

The number of Hispanic or Latino unemployment claimants increased 13 times between March and April, increasing from 757 to 9,841. In March of 2020, of the 7,400 unemployment benefit recipients, only about 10 percent were Hispanic or Latino; this share now stands at 17 percent. Black or African American workers who receive unemployment benefits saw a five-fold increase compared to a ten-fold increase among white workers, but they still make up the largest share of recipients. In April of 2020, Black or African American workers made up half of the recipients (down from 63 percent in March); and white workers made up 26 percent (up from 16 percent in March). Unemployment also increased rapidly among other race groups (mostly Asian workers): In March, only 284 workers from other race groups were receiving unemployment benefits; may April, this number jumped to 4,570 (a 15-fold increase).

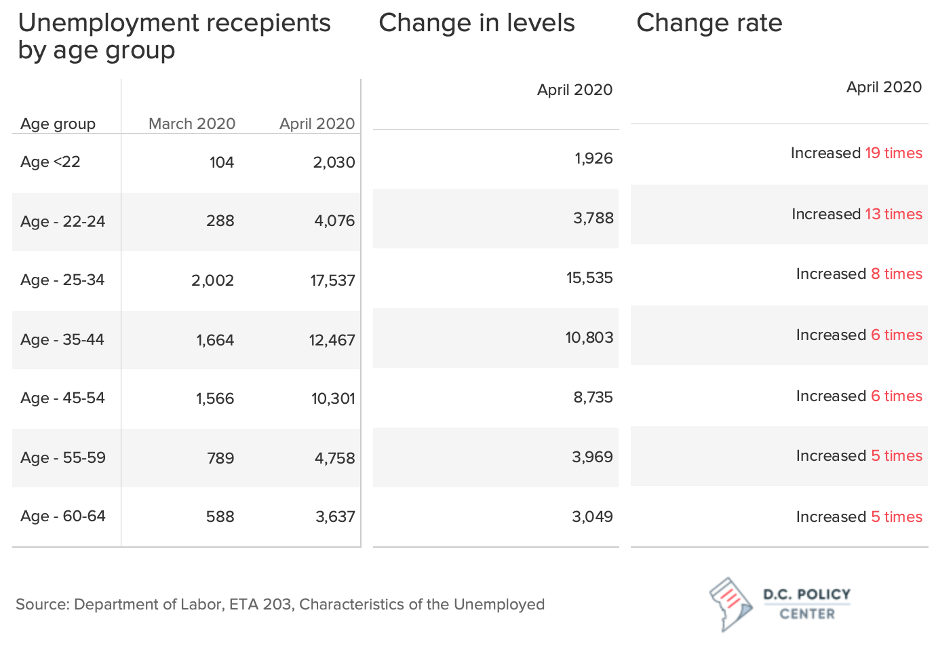

Younger workers now are a larger share of unemployment benefits recipients than what has historically been the case in the District of Columbia. Workers under the age of 22 made up under 1.5 percent of those who receive unemployment benefits in March; they are now about 3.7 percent (a 19-fold growth). Workers between the age of 22 and 24 who receive unemployment benefits increased 18-fold. Workers between the age of 25 and 34 have typically been the largest share of unemployment recipients (28 to 30 percent since the end of the Great Recession); and now account for an even larger share (32 percent in April). While older workers have not been spared from the impacts of the pandemic, they experienced job losses at a rate lower than the entire city. For example, the number of unemployment benefit recipients between the ages of 55 and 64 increased by 6,900, or five-fold since March, compared to a 6.6-fold increase for the entire city. This group now makes up about 15 percent of unemployment recipients, compared to about 19 percent in the last two years.

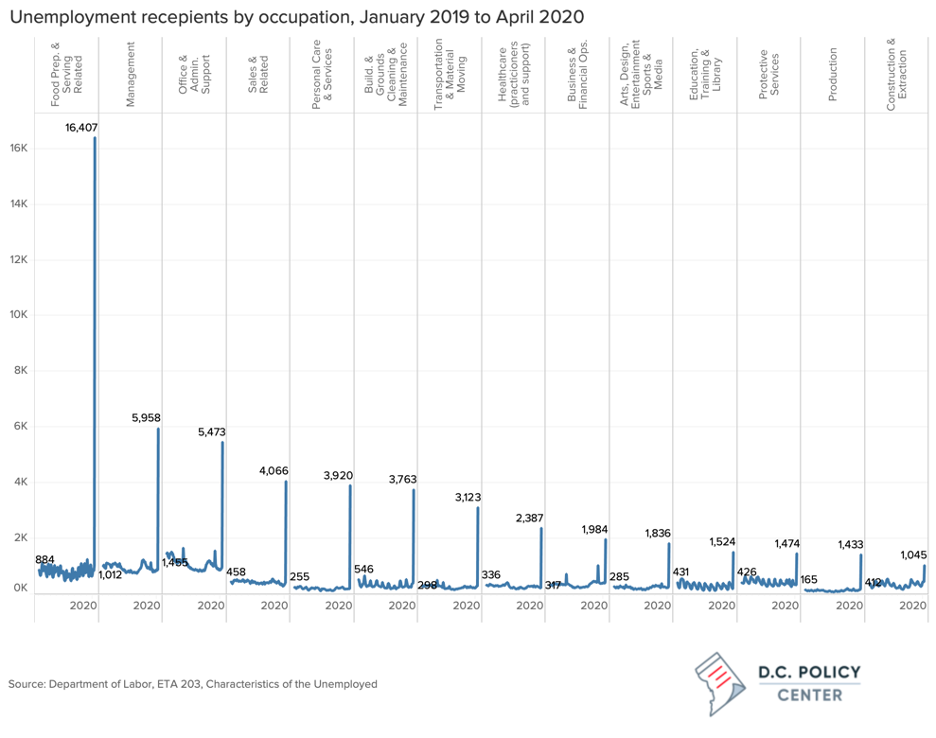

Unemployment recipients by occupation show losses across a broad spectrum of jobs.

Data on unemployment recipients show that the when a business closes, workers from a large range of occupations lose their jobs. For example, through April, jobs at restaurants declined by 33,200, but only about half of these workers were those employed in food preparation and service-related occupations. The rest were managers and those employed in back offices or in business support roles like HR managers or accountants. Management jobs declined by about 5,000; and unemployment recipients in these occupations are now at about five times their historic levels. Unemployment recipients who were in office and administrative support occupations increased by about 4,000. With a large share of the workers moving to telework, office buildings appear to have cut back some workers: unemployment claims among building and grounds maintenance workers increased by 3,200; and among protective services workers such as the security guards in buildings increased by about 1,000.

Workers with personal services jobs such as hairdressers or nail salon technicians also saw a high incidence of unemployment (an increase of from historically about 250 receiving unemployment benefits each month to nearly 4,000), even though industry level data which groups personal services under “other” did not experience any major declines. Finding a new job will be harder for those who have industry-specific occupations (such as food preparation workers), but those who can use their skills regardless of their industry (such as accountants) may be better positioned to return to work sooner.

Can the District reverse these losses swiftly?

The economic uncertainty makes it difficult to assess whether recovery will be as rapid as the decline. While there are some signs that economic activity is improving, a return to normalcy may take longer and hinge on whether businesses that cut back workers will be able to bring them back quickly.

First, consumers and businesses must be convinced that the health risks posed by the pandemic are abating. As the Georgia experience shows, reopening the economy by decree does not automatically mean economic activity will rebound. Georgia lifted the stay-at-home orders on April 24, but neither consumer spending nor the number of businesses that are open showed any change after the reopening. This suggests that until a cure or a vaccine is available, economic activity could be permanently depressed.

Second, establishment deaths will slow down rehiring. Some businesses will weather the economic downturn with barebone operations and will rapidly rehire when demand returns. But those that do not have the financial capacity to endure will permanently close. According to data from Opportunity Insights, as of May 15, 52 percent of small businesses in the District remained closed. Small businesses in the District of Columbia (establishments with fewer than 500 employees) account for 84 percent of private sector employment. If a substantial share of these businesses does not survive, the District’s ability to create employment will go down with them.

Finally, even in full recovery mode, the District may face a slower path of recovery if the pandemic permanently alters what is important to residents, businesses, and workers. A decline in the importance of business location, a loss of commuters and related economic activity, or an impaired demand for office space in the District of Columbia will make recovery harder.

About the data

Unemployment and employment data are from the Local Area Unemployment Statistics released on May 22 by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Unemployment by ward is released by the District’s Department of Employment Services. Industry level employment data are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics State and Metro Area Employment, Hours, & Earnings based on Current Employment Survey and from the District’s Department of Employment Services Wage and Salary Employment by Industry. Workforce by gender has been estimated by using the American Community Survey data from 2018. Characteristics of the unemployed are from the Department of Labor.