In mid-September, drawing on IRS migration data spanning from 2019 to 2021, researchers at the Office of Revenue Analysis in D.C. found that people who moved out of D.C. had higher average incomes than people who moved in. This trend resulted in a loss of taxable income for the District. Using last month’s release of the one-year American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS), we examined whether household migration trends from 2019 to 2022 tell a similar story, and whether anything changed in 2022.

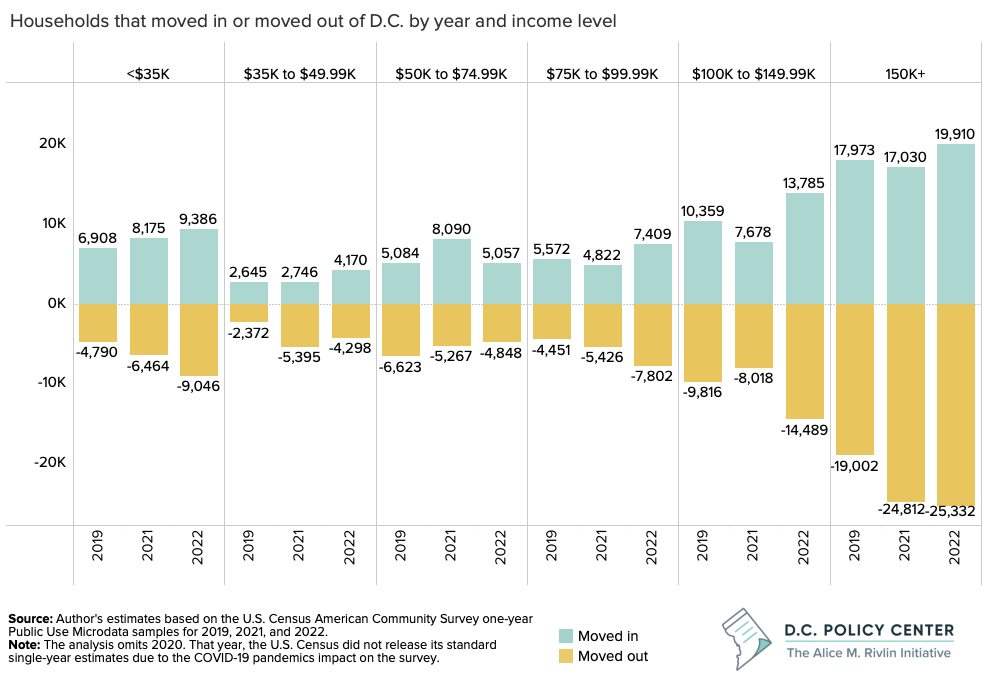

Using the ACS one-year microdata estimates, we analyzed household migration patterns in D.C. by household income brackets. Migration activity—that is, total households moving in or out of D.C.—varies considerably across household incomes. First, households with incomes above $150,000 are moving in and out of the city more often than households with lower incomes. Moreover, the households with higher incomes drive much of the migration activity. Second, households with incomes above $150,000 are leaving the city more often than they are moving in, leading to a strain on the population and taxable incomes. The number of households with lower incomes that have moved in is roughly equal to those that have moved out. But households with lower incomes account for a smaller fraction of total migration trends. Third, at every income level, households that moved into the city are smaller than those that moved out.

In 2022, the District has continued to lose households with high incomes faster than it has attracted them.

Using IRS data, the Office of Revenue Analysis in D.C showed that in 2021, out-migration was the norm for households with higher incomes. According to the ACS data, the District lost a total of 6,841 households to net out-migration in 2021. This loss largely coincides with the IRS data. The ACS data shows that the trend continued in 2022.

For households with incomes greater than $150,000, the District lost 7,782 households to net outmigration in 2021 and 5,422 households in 2022. While fewer households with high incomes left the District in 2022 than in 2021, it remained the case that households with high incomes continued to drive migration activity. After all, in 2022, the net gains or losses of households in the other income brackets never exceeded 1,000.

Out-migration from the District is driven by larger households, while in-migration is driven by smaller households.

We also examined migration trends by household size. This analysis revealed some interesting trends. First, averages across the three years, households that moved into the city are smaller than the households that moved out at every income level. This point is perhaps best seen by looking at the migration of households in the lowest income bracket. In 2022, for example, for every person that the District gained due to in-migration in this income bracket, it lost two people to out-migration.

Second, while the District experienced a net loss of family households with high incomes, it still managed to attract smaller, high-income households. This point dovetails with our previous research showing that D.C.’s household growth is predominantly driven by singles aged 25 to 34. In the future, the District might experience natural population growth as these smaller families increase in size. Whether the District substantially benefits from this natural growth will depend on whether the District can retain these families in the long run.

Retaining smaller households as they grow will be key to growing the District’s population and tax base.

The city’s continued appeal to smaller, higher-income households is a bright spot. But this trend has not been strong enough to counterbalance the leakage of population via out-migration at almost all income levels. While the loss of families is not a new trend for the District, the recent past is instructive: Through the 2010’s, the District grew its population and income tax base by attracting singles and couples, and retaining them as they formed families and grew their incomes. All in all, these trends highlight the importance of creating a policy environment that incentivizes housing production at all income levels, and for all kinds of families.

Data Notes

- All estimates were calculated using the one-year estimates from the American Community Survey microdata for years 2019, 2021, and 2022.

- Household income brackets are presented in 2022 inflation-adjusted dollars.

- We omitted the year 2020 because the U.S. Census Bureau did not release its standard single-year estimates and microdata for 2020 due to the non-response bias created by the outbreak of COVID-19.

- While our analyses suggest that the District likely lost income to net out-migration, these results should be interpreted with caution. Unlike the IRS migration data which includes summaries of taxable income, the American Community Survey tracks households and household income. But not all these households are tax-paying, and not all the household income is taxable.

- ACS is a survey and subject to sampling error.