On September 24, 2024, Executive Director Yesim Sayin testified before the D.C. Council Committee on Housing. Her testimony focuses on housing as an economic development strategy. Read the full testimony below or download the pdf version.

Good afternoon, Chairman White, and members of the Committee on Housing. My name is Yesim Sayin, and I am the Executive Director of the D.C. Policy Center—an independent non-partisan think tank advancing policies for a strong, competitive, and compelling District of Columbia. I am grateful for the opportunity to testify on opportunities to increase housing in Downtown D.C.

With remote work breaking the relationship between where we live, and where we work, housing should be viewed as a key economic development policy.

Residents used to move to the city for jobs and move out of the city for housing.[1] With remote work breaking the relationship between where we live and where we work, housing, alongside public safety and city amenities, has become increasingly important in attracting new residents. D.C. must become a city with an abundance of housing, an abundance of good-paying jobs, an abundance of safe neighborhoods with an abundance of amenities, an abundance of affordable childcare, and an abundance of good schools. And Downtown provides an opportunity to test this vision.

Downtown office market shows little sign of improvement.

The persistent hold of remote work has transformed the District’s downtown and its economy. The pandemic has ended, but remote work has not. In a typical month, less than half the office workers (excluding federal government employees) commute to work, with only a minor uptick since the beginning of 2023.[2] The reduced demand for office space has led to substantial distress in the office market and large discounts on office valuations. For example, since January 2023, 21 large office buildings (over 50,000 sq. ft.) were sold at an average discount of 42 percent compared to their 2023 assessed values.[3]

The Central Business District (CBD) and the East End, the city’s most office-dense areas, are particularly affected, with a vacancy rate nearing 19 percent by mid-July.[4] Availability rate, which includes both vacant space and space with an expiring lease, reached nearly 25 percent—an all-time high for these two submarkets, signaling that vacancy has not stabilized.

As vacancy rates rose, annual office gross rents for the District fell below their 2019 level, even without adjusting for inflation. But these discounts did not stimulate demand: Since January 2023, the District’s office market had a negative net absorption of roughly 1.5 million square feet, meaning more space has been vacated than leased across the city. Net absorption has remained negative for the first seven and a half months of 2024. The impact has been particularly heavy in the CBD and the East End, both of which experienced continuous negative absorption since the second quarter of 2020 and collectively lost leases for over 31.2 million square feet of office space, which is the equivalent of about 30 percent of total office inventory across these two submarkets.[5]

An ailing office market presents significant fiscal risks to the city’s economy.

The District’s fiscal picture reflects these economic hardships. The District has yet to right-size its budget after a significant spending growth which was financed by the federal fiscal aid between 2019 and 2024. During this period, local fund spending increased by 34 percent whereas local fund revenue increased by 19 percent. As a result, in this budget cycle, despite raising taxes by nearly $2.5 billion over the financial plan period,[6] the city is still projected to deplete $2.3 billion from its savings to pay for recurring expenditures in excess of recurring revenue[7]. By 2029, the city is projected to face a $760 million deficit,[8] with only $960 million in usable reserves in hand, according to current projections. [9] At this rate, the city will run out of money by 2030.

In this difficult environment, a slow transformation of the downtown from office to other, more valuable, uses will only increase the fiscal risk.

The tax abatements in place for downtown conversions have the potential to support the production of 16,000 new units.

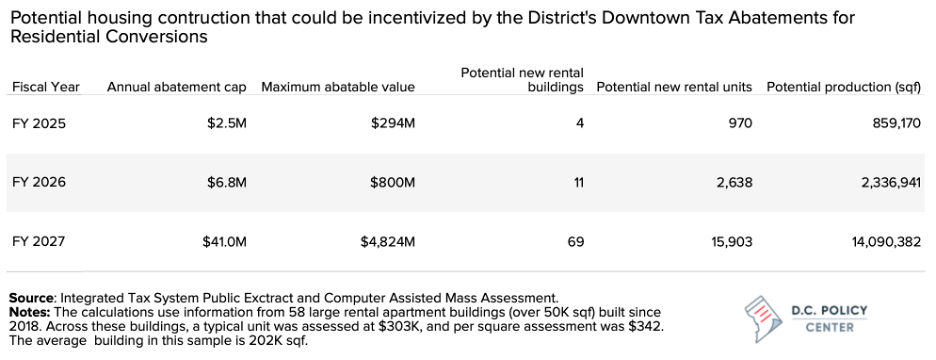

In 2024, the District launched a new Housing in Downtown program to incentivize office-to-residential conversions. The program offers a 20-year tax abatement, a 10-year exemption from the Tenants Opportunity to Purchase Act, and an exemption from the District’s First Source requirements for construction for any office-to-residential conversion that produces at least 10 units.[10] Given the abatement caps, by Fiscal Year 2027, the program has the capacity to add 69 new residential buildings to Downtown, with a potential of 16,000 new residential units in 14 million square feet of converted office space. If this type of development happens, it will forever change Downtown, making it a vibrant place with robust economic activity, and tremendous fiscal value.

The city needs to do more to hasten the pace of housing production in Downtown.

Given this investment, the most important task for the District is to eliminate as many barriers as possible to make this program a success. We recommend the following to maximize housing production in Downtown D.C.

- Reclassify commercial-to-residential conversations at time of permitting (Recommendation in the Tax Revision Commission’s Chairman’s Mark).This will allow conversions to benefit from the tax abatements sooner, reducing the cost of projects.

- Eliminate the 70 percent rule for deed taxes. At present, if a building trades at a price lower than 70 percent of its assessed value, the deed taxes are calculated at the assessed value, and not at the transaction price. This rule made sense when the District’s commercial values were increasing, but as noted, transactions at a deep discount are becoming the norm, not the exception. The higher deed tax obligation distorts the market, and at the margin, will stop some transactions and slow down the conversion process. The city should consider eliminating this rule or allowing trading parties to submit an appraisal for the calculation of deed taxes.

- Allow demolitions to qualify for tax abatements. As shown in the table above, if fully deployed, the Housing in Downtown program can support up to 16,000 units in 69 buildings. Given the architecture of office buildings downtown, there may not be 69 buildings that can be feasibly converted, but there might be properties where a full demolition might make financial sense. These projects should also be eligible for tax abatements.

- Find a cheaper way of creating affordability downtown. The projects eligible for tax abatements under the Housing in Downtown program must set aside at least 10 percent of their units at affordable rents at 60 percent of Median Family Income or 18 percent affordable at 80 percent of Median Family Income. While the goal to have an inclusive Downtown with affordable housing is commendable, the affordability requirements will add to the costs, and slow down production. The city should consider using alternative tools such as buying down rents (the Cash for Covenants program).

- Cut red tape. Permitting, inspections, and zoning reviews add delays and costs slowing down housing production. The District should invest in capacity in the Office of Planning and the Department of Buildings to expedite these processes.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I welcome any questions from the Committee.

[1] Yesim Sayin, Residents move into the city for jobs, move out for housing, District Measures, ORA. June 15, 2015. Available at https://ora-cfo.dc.gov/blog/residents-move-city-jobs-move-out-housing

[2] Data from Kastle shows that the share of workers swiping their access cards increased by 4.7 percentage points between January 2023 and June 2024.

[3] Costar sales data for large office buildings between January 1, 2023, and June 30, 2024. This number excludes buildings.

[4] The ‘East End’ is a submarket in downtown D.C. as defined by Costar. The East End submarket’s approximate boundaries are 22nd Street NW on the west side, 3rd Street on the east side, P Street on the north side, and Constitution Avenue on the south side.

[5] Costar data for CBD and East End.

[6] ORA Fiscal and Legislative Analysis Team, Revenue Provisions in DC’s New Budget, September 10, 2024. Available at https://ora-cfo.dc.gov/blog/revenue-provisions-dc’s-new-budget.

[7] FY 2025-28 Budget and Financial plan.

[8] This includes $401M of fund balance use in FY 2028 and $359M of recurring services with one-time funding in FY 2025.

[9] Excludes reserves required for debt service, federally required reserves, and reserves already committed for other uses. Data from an OCFO presentation delivered at a Federal City Council meeting in June 2024.

[10] Washington DC’s Housing in Downtown Program, Program Explainer Deck, September 2024. Available at https://dmped.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dmped/page_content/attachments/Housing%20in%20Downtown_DMPED%20September%202024%20%281%29_0.pdf