On Monday, March 3, 2025, Director of Policy and Research Emilia Calma testified before the DC Council Committee on Housing. Her testimony focused on ways to increase housing availability and affordability in the District. Read the full testimony below or download the PDF version.

Good morning, Chairperson White and members of the Committee.

My name is Emilia Calma and I am the Director of Research and Policy at the D.C. Policy Center, an independent nonpartisan think tank advancing policies for a strong, competitive, and vibrant economy in the District of Columbia. I am speaking today about the importance of increasing housing development in D.C. and methods to create affordable housing immediately and in all areas of the city.

Housing production is needed to ensure the District’s future

For decades, Washington, D.C. experienced growth from abundant job opportunities that attracted new residents and spurred population increases. Now, more people are working remotely, commute times matter less,1 and the federal workforce is less stable. Because of these factors and more, the availability of housing is crucial to attract and retain new residents.2 Housing is more than just shelter—it is a fundamental engine of economic growth, fiscal stability, and a magnet for residents. This focus is particularly urgent given the city’s stagnant revenue growth and the significant drop in housing permits.3

To create greater housing availability and affordability, the city must make changes to the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) and Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) to make it easier for housing to be produced and create affordability through rent supplements rather than production.

Almost all rental housing in multifamily buildings in D.C. has some government intervention

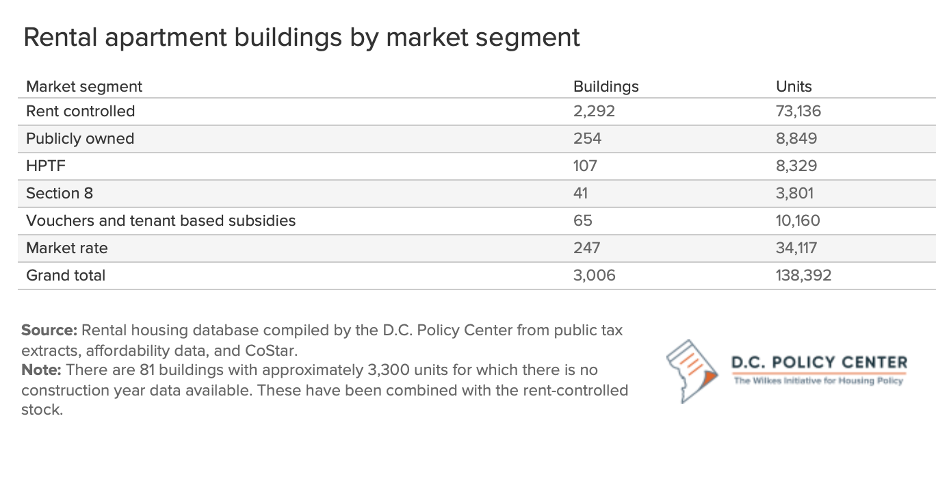

There are 3006 apartment buildings with 138,391 rental units in D.C., representing 69 percent of all rental housing units in the city. Just over half of these units (53 percent) are subject to rent control, about 22 percent are affordable through housing subsidies (31,139 units),4 and another 3 percent (4,400 units) have been created using Inclusionary Zoning (IZ). This means that only 21 percent of D.C.’s rental units (29,717) are truly market rate,5 or without any government subsidies, affordability requirements, or rent restrictions.6

Preservation through buying down of rents can create affordable housing in high demand areas of the city

The District of Columbia faces significant challenges in providing affordable housing. D.C. has relied on capital subsidies to ensure housing affordability, but this model has become financially unsustainable as revenue growth and contributions to the HPTF have slowed. According to the D.C. Policy Center’s analysis of HPTF reports, each affordable unit funded in 2022 cost over $530,0007—more than the cost of many market-rate luxury apartments.8 Additionally, most of these units are concentrated in Wards 7 and 8, reinforcing patterns of segregation. With competing budget priorities, the District must be strategic about how it uses its funds, ensuring that money spent is making the highest impact.

By shifting resources from capital subsidies to operating subsidies or rent supplements, the city can create affordable units in highly resourced areas of D.C. for a fraction of the cost of new production. By relaxing capital affordability requirements, potentially allowing for higher AMI levels such as 80%, projects would demand less capital subsidy. The savings could then be redirected as operating subsidies or rent supplements to achieve deeper affordability through covenants.

In 2020, the D.C. Policy Center first introduced the concept of inclusionary conversions9 as an alternative to producing new affordable housing units. The city adopted this model10 under the name “Cash for Covenants”11 and has used it to create affordable units as a part of Mayor Bowser’s 36,000 new housing goal.12 This method is more cost effective than new construction and inclusionary zoning (IZ) and can produce affordable units immediately. For example, investing $85 million annually in this approach could deliver 3,000 affordable units for fifteen years for households earning 50 percent of the Area Median Income. In contrast, at current costs, the same amount would produce only 160 units per year through HPTF.13

Thank you for your time. I look forward to answering any questions you may have.

Endnotes

- Sayin Y. (2021). The declining importance of commute times.” D.C. Policy Center. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/the-declining-importance-of-commute/. Additionally, recent research shows that the distance between where people live and where they work increased for those who have been hired since the COVID-19 pandemic began. The mean distance rose from 10 miles in 2019 to 27 miles in 2023, and the share of workers living more than 50 miles from their employer rose 7-fold from 0.8% to 5.5%. For details, see Akan, et. al. (2024). “Americans Now Live Farther from Their Employers.” WFH Research. Available at https://wfhresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/DistanceToWork.pdf

- Trueblood, A. (2024, July 31). Housing for workforce is a key economic development program. D.C. Policy Center. https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/housing-for-workforce-is-a-key-economic-development-program/

- In 2024, there were permits for only 1,239 multifamily units – a significant drop from previous years. For example, in 2022 there were 7,234 permitted units. Census Building Permit System (BPS) Available at https://www.census.gov/construction/bps/index.html

- This includes 8,849 units that are in publicly owned buildings, 8,329 units created with HPTF subsidies, 3,801 units created with project-based section 8 housing vouchers, and 10,160 units made affordable through tenant-based rental subsidies.

- The numbers in the table for market rate housing include 4,400 IZ units. Removing those from the count leaves the total market rate units at 29,717.

- These numbers are from our analysis of the rental market in our upcoming paper about the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA). This paper will be released on March 12, 2025.

- Data includes 7 major rehabilitation and new construction projects reported in the 2022 Annual Report for the Housing Production Trust Fund, which collectively cost $769 million to produce 1,443 units. This is the full cost of the project, funded through multiple funding streams in addition to HTPF.

- A review of projects delivered in 2023 show that the average cost per unit was 463,000. Data from WDCEP 2023/24 Economic Development report.

- Sayin, Y. (April 1, 2020). Appraising the District’s rentals – Inclusionary Conversions. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Rental-Housing-Report.Final_.March-15.pdf

- Austermuhle, M. (December 16, 2021). Bowser Unveils Plans for More Affordable Housing West of Rock Creek Park. Available at https://dcist.com/story/21/12/16/bowser-dc-affordable-housing-rock-creek-park/

- Development Review Zoning Initiatives for Affordable Housing in FY 2022. (December 16, 2021). Available at https://planning.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/op/page_content/attachments/OP%20Zoning%20Initiatives%20for%20Affordable%20Housing%20in%20FY%202022.pdf

- Data breakdown available at https://open.dc.gov/36000by2025/

- Sayin, Y. (April 1, 2020). Appraising the District’s rentals – Inclusionary Conversions. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/appraising-districts-rentals-chapter-v/