The Neighborhood Engagement Achieves Results (NEAR) Act was passed by the Council of the District of Columbia in March 2016 in response to an increase in homicides the previous year. Its goal was to reduce violence in the District, but instead of perpetuating broken and ineffective “war on drugs”-style methods, it uses a community-based public health approach to violence prevention and intervention that is based – in part – on an innovative model pioneered in Richmond, California. The Mayor’s budget for the 2018 fiscal year would fully fund this groundbreaking legislation for the first time, and should be passed by the Council at the funding and staffing levels proposed by the Mayor.

Introduction: The creation of the NEAR Act

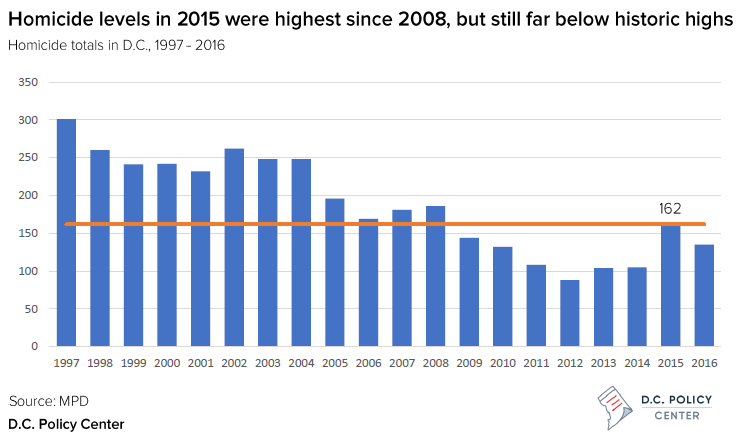

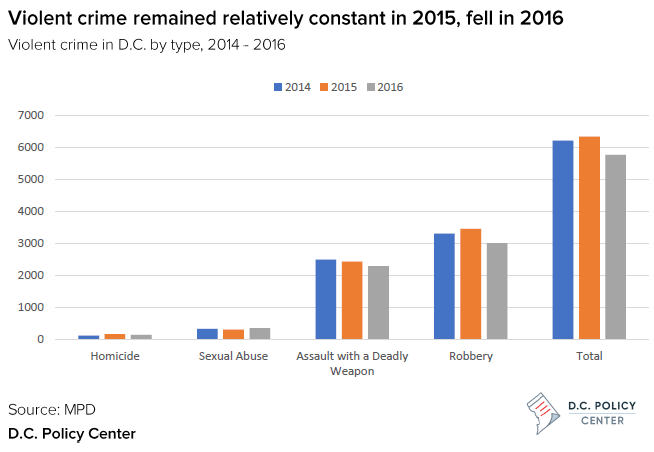

In the summer of 2015, the District of Columbia experienced a surprising uptick in the number of recorded homicides, with the year-end total rising from 105 in 2014 to 162 in 2015 – the highest total since 2008.[1] Interestingly, violent crime rates in the District remained relatively constant in 2015 even as homicides rose.[2]

In the ensuing months, Mayor Muriel Bowser and the Council of the District of Columbia – led by Councilmember Kenyan McDuffie, who chaired the Judiciary Committee – developed and introduced significantly different proposals to address the sudden rise in homicides.

Both proposals received considerable criticism, with community advocates comparing the Mayor’s proposal to “the failed ‘tough on crime’ experiments of the 1980s and 1990s,” that contributed to the nation’s mass incarceration crisis without improving public safety. Conversely, Councilmember McDuffie’s proposal, and the model upon which it was partially based, was frequently portrayed as “paying criminals to stay out of trouble,” which felt like an insult to some law-abiding residents.

Ultimately, the Council unanimously passed the Neighborhood Engagement Achieves Results (NEAR) Act, which was introduced by Councilmember McDuffie and had been amended to include several provisions from the Mayor’s earlier proposal. However, the discourse surrounding the bill had become so polarizing that neither the Mayor nor the Council fully funded the NEAR Act in the FY 2017 budget, a surprising step-back that brought its own criticism and concern from the advocacy community. Now, a year later, the Mayor has quietly proposed fully funding and implementing the NEAR Act in the FY 2018 budget.

The NEAR Act: A public health approach to reducing violence in the District

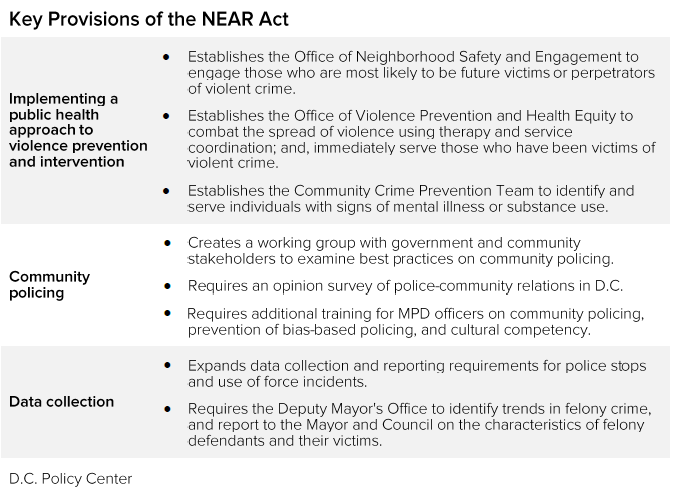

The NEAR Act primarily addresses policing reforms and employs a public health approach to reducing violence, meaning that it seeks to identify and address the root causes of crime in a long-term and sustainable way. In this way, the NEAR Act eschews the traditional law enforcement suppression strategies that can lead to increased arrests and incarceration. Many in D.C.’s criminal justice reform circles have high hopes for the Act, as it represents the type of change that advocates and community members have sought for years.

The two aspects of the NEAR Act that have received the most attention are the creation of the Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement (ONSE) and the creation of the Office of Violence Prevention and Health Equity (OVPHE). The OVPHE seeks to employ a violence interruption model that places trained staff from nonprofit organizations at hospital emergency rooms. The Mayor’s Office is implementing this provision by focusing on the emergency room trauma centers that treat the vast majority of the District’s gunshot and stabbing victims. At the trauma centers, trained clinicians provide immediate care and services to the victim and their immediate family. The program was launched at MedStar Washington Hospital in FY 2016, and will expand to Prince George’s Hospital Center and Howard University Hospital during FY 2017 and FY 2018, and to George Washington Hospital in FY 2019.[3]

Other major components of the NEAR Act include training for MPD officers on community policing, bias-free policing, and cultural competency, as well as new surveys and data collection to assess the current relationship between MPD and District residents and to better track trends in crime, police stops, and use of force.

The Act also specifically seeks to improve interactions between law enforcement and people with mental illness or substance use disorders by pairing police officers with mental and behavioral health clinicians for certain types of 911 calls. This approach aims to get people the medical care and social services they need without unnecessarily relying on the justice system and, in the process, subjecting people to the onslaught of collateral consequences that accompany an arrest and prosecution. Other jurisdictions, such as Seattle and Denver, have seen early successes with similar programs.

The table below provides an overview of the key provisions of the NEAR Act; a full list of all twenty titles and subtitles of the Act is available in the appendix (PDF) at the end of the piece.

Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement

The most controversial component of the NEAR Act is the creation of the Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement (ONSE), which seeks to engage those who are at high-risk of participating in, or being a victim of, violent crime. ONSE is modeled after the Office of Neighborhood Safety (ONS) in Richmond, California, but differs in that participants will be paid for a more clearly defined set of activities that can be justified under audit, making the D.C. model slightly less daring and more politically palatable.

In Richmond, ONS works with community partners, including law enforcement, to identify those who are most likely to be involved with gun violence.[4] ONS engages those individuals through the Operation Peacekeeper Fellowship; each fellow develops a customized “life map” and receives monthly stipends for making progress towards their goals. The program has been lauded for contributing to a drastic reduction in homicides and firearm assaults between 2007 and 2013, a significant accomplishment for a city that previously ranked as one of the most dangerous cities in the United States.[5]

ONS has also been criticized for “paying people not to kill.” In the most extreme cases, participants who are suspected of being involved in a homicide—but who are not arrested or charged—may continue to engage in the program. In addition, there have been moments of high-profile tension between ONS and the Richmond Police Department that have been attributed, in part, to an unwillingness by ONS to cooperate with police in order to maintain trust with the fellows and other community members.

While the Richmond ONS is an intriguing model that has garnered national attention, and may soon be replicated in several jurisdictions besides D.C., it is important to note that the Richmond program has never been fully evaluated nor replicated. And, while ONS was taking root in 2007, Richmond was experiencing other significant changes – most notably the appointment of former Police Chief Chris Magnus, who introduced wide-ranging departmental reforms including a focus on community policing. It is, therefore, difficult to quantify the impact of ONS in reducing firearm activity. In addition to some of the questions surrounding the Richmond model, Richmond and D.C. have significant cultural, political, and size differences that do not allow for an identical replication of the Richmond program. The D.C. population is more than six times as large as Richmond’s, and while officials in Richmond could identify fewer than 20 individuals who were believed to be responsible for 70 percent of firearm activity in 2007, officials in the District believe that firearm activity is more dispersed. Another significant difference is that the fellows in the Operation Peacekeeper Fellowship receive stipends that are paid for with privately raised funds that have fewer reporting and oversight requirements than the spending of public funds. As outlined below in greater detail, Mayor Bowser proposes to use public funds for all aspects of ONSE, therefore requiring the District to be somewhat more restricted in how it spends and tracks the payments that participants receive.

The NEAR Act in the Mayor’s Fiscal Year 2018 Budget Proposal

The Mayor’s 2018 Budget Proposal seeks to fund and fully implement all NEAR Act provisions. In lieu of participant stipends, the Mayor’s Office has proposed using $4.2 million in workforce development funding under the Department of Employment Services Career Connection Fund to serve 200 participants (4 cohorts of 50 participants, for 9 months each). In so doing, the District will dedicate significantly more funding for participant wages than was anticipated by the CFO’s Fiscal Impact Analysis of the NEAR Act. In addition, the Mayor proposed 30 full-time employees (FTE), including 20 Roving Leaders from the Department of Parks and Recreation, rather than the nine FTE predicted by the CFO.[6][7] In total, the Mayor’s FY 2018 budget would fund the Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement at a level that is nearly five times higher than the CFO estimate, a strong statement of support for a once-controversial piece of legislation.

Creating stronger and safer communities in the District

The question that D.C. residents want answered is, “will this make us safer?” The answer is “yes.”

In 2016, the District experienced a decrease in the number of homicides from the prior year, though the number remained above 2014 levels when D.C. was near historic lows. As of May 2017, D.C. appears to be on-track to finish the year at or below the 2016 levels.[8] The NEAR Act brings forward several promising and evidence-based practices that should contribute to further reductions in violence in the District.

The NEAR Act strongly emphasizes a public health approach to violence prevention and intervention, which seeks to address the underlying causes of violent crime rather than only focusing on the symptoms of violence (e.g., a violent act). This approach is consistent with national and international best practices, and is advocated for by the World Health Organization and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. From helping to develop safe and nurturing relationships between children and their caregivers to providing victims of violent crime with immediate care and support, a public health approach can take numerous forms that are rooted in evidence. Unlike a police suppression model that exclusively focuses on (temporarily) punishing people who commit violent acts, a public health approach focuses on preventing violence and advancing the sustained safety and stability of the communities most-impacted by violence. By engaging those who have been recent victims of violent crime and those who are most likely to be future victims or perpetrators of violent crime, and providing them with social services and employment opportunities that can change their life trajectories, the District will be making a long-term investment in its safety.[9]

In addition to the public health approach to preventing violence, cities across the nation have recognized that improving the relationship between law enforcement and the communities they serve is critical to advancing safety for the police and community members. The research on this topic is clear: Communities and officers are both safer when they share a strong and trusting relationship. Community members are more likely to report crimes and come forward as witnesses when they trust law enforcement and view them as a legitimate and protective entity in their community. Under the leadership of President Barack Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder, Jr., the Department of Justice launched the National Initiative on Building Community Trust and Justice, an effort to improve relationships and increase trust between communities and the criminal justice system.

The NEAR Act attempts to marry both concepts – a public health approach to violence prevention and intervention, and improving the relationship between the community and MPD. District of Columbia elected officials deserve credit for passing legislation to identify and proactively serve the D.C. residents who are most likely to participate in, or be a victim of, a violent crime. Implementing this approach, coupled with the community policing and other public health reforms put forward in the NEAR Act, should contribute to a decline in future violence.

The District cannot wait another year for the NEAR Act to be fully funded

While violent crime continues to be lower than it was during the 1990s and early 2000s, there are still far too many D.C. residents who are exposed to violence. The District cannot wait another year for the NEAR Act to be fully funded. For the long-term safety of the District, and especially for the D.C. communities that are most impacted by violence, the Act must be fully funded and operationalized during the Fiscal Year 2018 budget cycle, and the Council should provide the necessary resources to staff the office at the levels proposed in the Mayor’s Budget.

About the data

Homicide Chart data source:

Violent Crime Chart data source:

- 2014 & 2015 data: MPD 2015 Annual Report(p. 24) (footnote #2)

- 2016 data: MPD https://mpdc.dc.gov/page/district-crime-data-glance