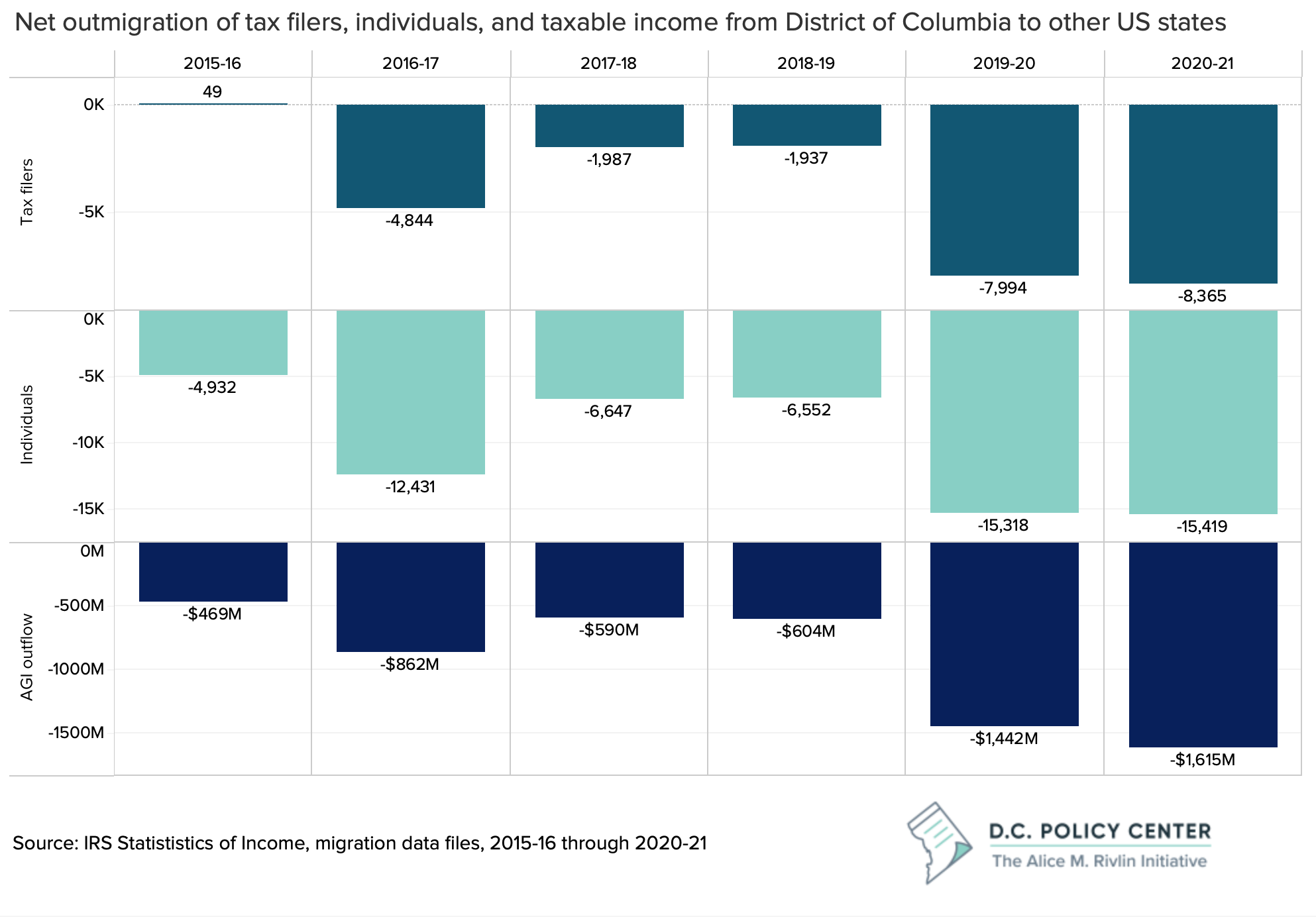

Recently published migration data compiled by the IRS using addresses on federal income tax filings provide additional insights on the pandemic-induced exodus from the District of Columbia (national analyses here). According to these data, between tax years 2020 and 2021, net outmigration (inflow minus outflow) from the District added up to 8,365 tax filing units made up of 15,429 individuals. Collectively, this net outflow resulted in a loss of $1.6 billion in adjusted gross income (AGI).

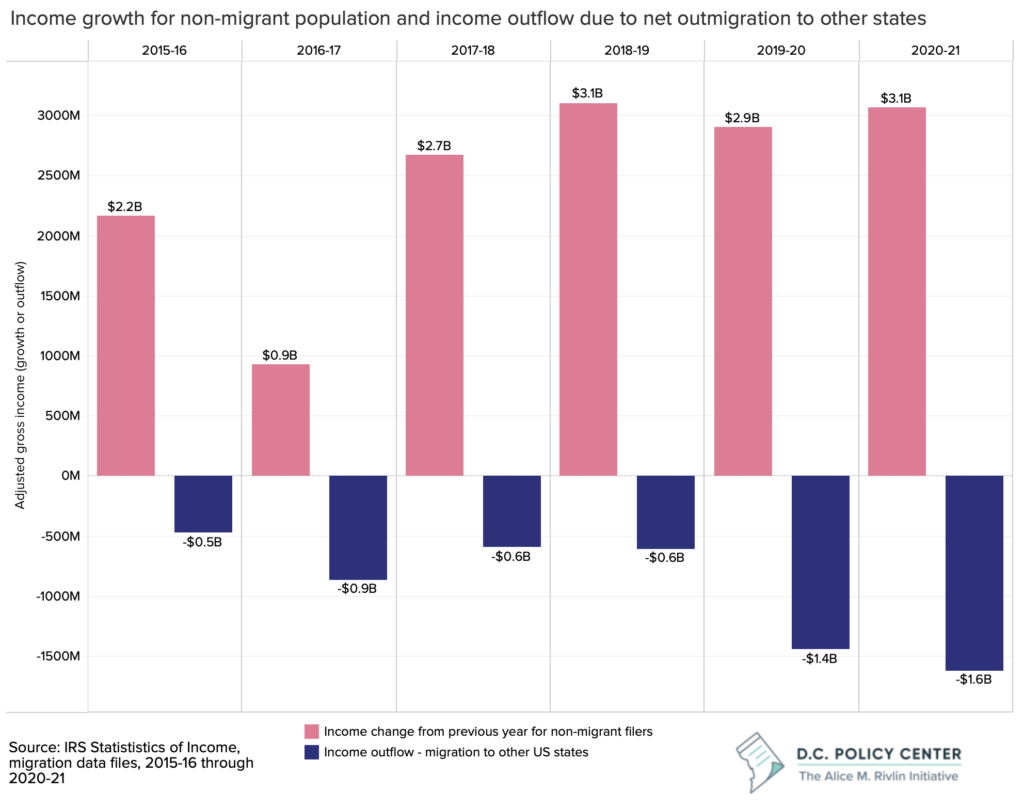

Such net outflow of taxpayers is not new for the District. Even prior to the pandemic, net outmigration has been the norm for D.C. per income filing data, albeit in smaller numbers. But this trend is not obvious in the income tax collection data. The city has been able to make up for the lost income due to outmigration through the rapidly growing incomes of non-migrating residents. For example, between 2015 and 2016, outmigration of taxpayers, on the net, cost the city nearly half a billion dollars in taxable income. But the taxable incomes of residents who did not migrate to another state grew by $2.2 billion, more than making up for the losses tied to the incomes of those taxpayers who left. Similarly, between 2020 and 2021, non-migrant resident incomes grew by $3.1 billion, or double the income lost through outmigration.

We should be careful interpreting these numbers. IRS migration data is definitely at odds with the U.S. Census population data (which showed a loss of 6,624 residents between 2020 and 2021 or less than half of what IRS data suggests). This could be a function of timing, or part-time filers who may have filed taxes in a different state per address data but counted toward D.C. for U.S. Census population estimates.

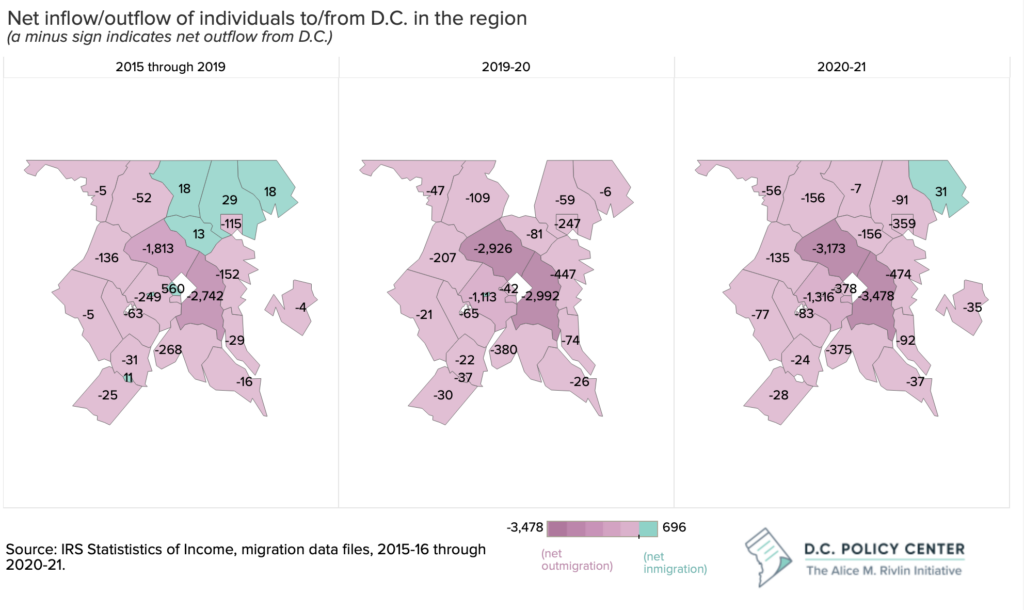

There is, however, more, we can mine out of the IRS data. For example, where do people move to, if they leave D.C? Looking at data dating back to 2015, we find that in the Washington metropolitan region, Prince George’s County and Montgomery County has been on the top of the destination list for former D.C. residents, and this trend only strengthened since 2020. Suburbs of Virginia closest to D.C. also became more attractive. For example, Arlington was a net exporter of residents to D.C. before 2020, but since then, it has been a net recipient.

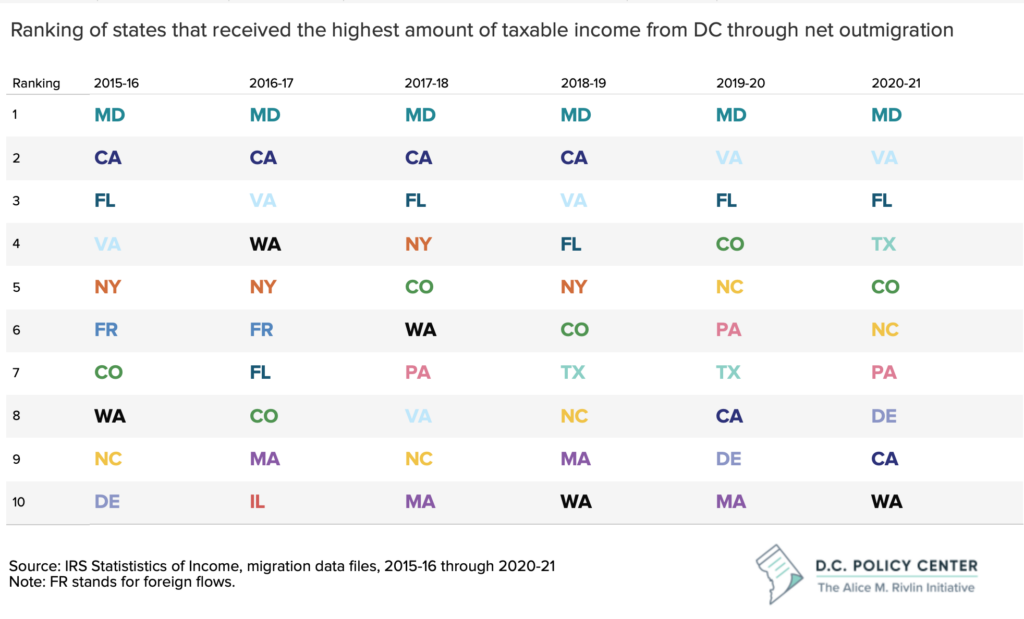

The increasing allure of cheaper and smaller locations can also be seen at the state level. California was second on the list of destinations for former D.C. residents up until the pandemic, but since 2020, its rankings have fallen to 8th and 9th. Similarly, New York state is no longer on the list of top ten destinations for former D.C. residents, even though it was in the top five in years before the pandemic. Virginia, Florida, Texas, North Carolina, and Colorado have either raised in ranking or preserved their positions since the beginning of the pandemic.

Cities, including D.C., always have a natural churn of residents, but the pandemic has exacerbated this in a way that puts D.C. at risk of losing more residents to lower cost places or suburban places than typical years. Most recent population data for 2022 suggests that net outmigration from D.C. to other U.S. locations has slowed down. That is good news, but the city must still strive to attract and retain residents to secure its fiscal future.