D.C.’s parents are in a bind. While the District offers free pre-K for its three- and four-year-olds, finding high-quality child care from a licensed provider for infants and toddlers is challenging at best.

D.C.’s licensed child care capacity for children under age three is limited, and the spots that are available are not cheap. The typical cost of care for an infant with a licensed child care providers (i.e., those who are licensed by the District and meet certain health, safety, and educational requirements) is around $1,800 per month for center-based care. These high prices are partly the result of providers’ high costs, driven by high rents, regulatory requirements, and large labor costs that follow from high staff-to-child ratios—even as teachers and other workers at licensed facilities face low pay and few benefits. A large portion of child care facility owners have difficulty operating on revenue alone.

High costs mean that even middle-class parents struggle to afford licensed child care, and low supply means that parents who can afford tuition at a licensed care facility often face long wait lists. Those with the means often turn to alternatives like private nannies or au-pairs; those without may turn to family or friends, unregulated child care providers, or resort to one parent dropping out of the labor force.

Looking for clues in D.C.’s baby boom

We know there is a child care crisis in the District, but exactly how big is the “child care gap”? The truth is, we don’t have a lot of data about the precise child care needs of families in the District.

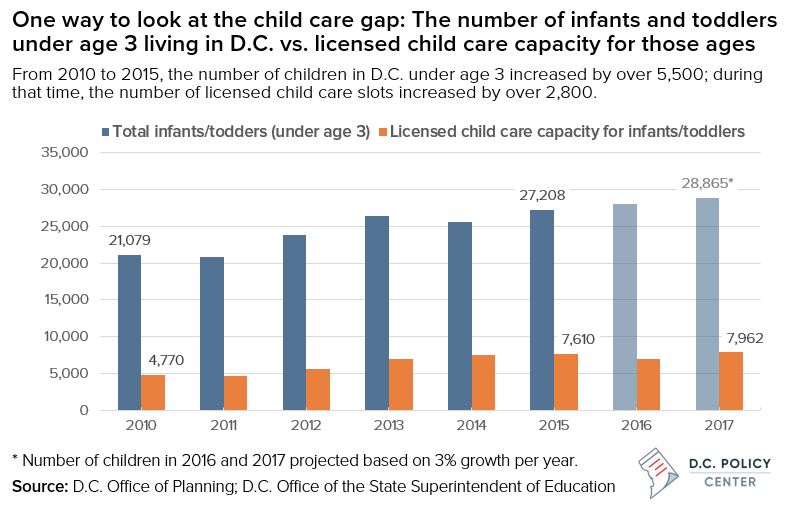

Between 2010 and 2015, the number of children in D.C. under age 3 increased by over 5,500—with much of that growth occurring between 2010 and 2013. There are now over 26,500 infants and toddlers under age 3 in the District, and only about 7,600 licensed child care slots. This difference—between the total number of infants and toddlers, and the number of licensed slots—is frequently cited as the size of D.C.’s child care gap.

The contrast between the number of children living in D.C. and the number of licensed spots available for those children is a good first step to understanding the current gap—but get to the real story, we need to look at the more complicated picture of supply and demand in the District and the broader metro area.

What types of care do parents choose, and why?

The first challenge in measuring the overall child care gap is that not all parents of infants and toddlers are seeking to place them in licensed child care providers. All sorts of factors—socioeconomic status, employer’s policies, presence of family in the area—can affect parents’ preferences and ability to pay for licensed care.

To begin with, some parents—particularly mothers—may drop out of the labor force entirely when they have children, either due to personal choice or economic necessity. Those who continue working also turn to many types of care. National research has found that more than six in ten employed mothers with children under age 3 will use some form of child care outside the home, but the context in which they make this decision is influenced by many factors. These factors include the parents’ income, education level, and marital status, as well as the quality, cost, and availability of care situations available.

All these variables complicate the picture of child care demand in D.C., especially as the District contains a high level of inequality within its border, including for parents: In Ward 8, where the child poverty rate is almost 50 percent, the median income of families with children is $24,096, according to ACS estimates compiled by Kids Count. In Ward 3, where the child poverty rate is less than 3 percent, the median income of families with children is $216,193. D.C. does offer vouchers for subsidized care for low-income families, but it is unclear how many eligible parents know about subsidized care and are able to access it, and the extent to which subsidized care meets the needs of parents with irregular or nonstandard work schedules.

What do working parents do when they don’t use licensed child care providers? The answer to that is also complicated. Among parents who continue working, some place their youngest children in family members’ care, or turn to unlicensed, unregulated daycare facilities. Other parents—particularly those in higher-income households—employ nannies or participate in nanny-shares. Once again, some of these decisions are based on parents’ preferences about types of care, but others are driven by the scarcity and expense of the current child care market. More research is needed to understand how parents’ decisions would change if licensed care in the District had more availability, lower prices, or higher quality.

Geographical mismatches and missing commuters

D.C.’s unique employment patterns also complicate the picture of child care supply and demand. It’s true that we know where children in D.C. live, and where licensed child care facilities are located; we can even map various factors that might affect demand. Theoretically, this would tell us where the greatest demand is located, and where families’ needs are not met. This type of data is very helpful, but there is also a lot variability in where parents might seek licensed child care.

One of the biggest issues with predicting demand based on where children live is that parents may prefer to use a care provider near their workplace—or where older children attend school—rather than near their home. And we shouldn’t forget that D.C. is at the center of a larger metropolitan region—and it’s unclear how much commuters from Maryland and Virginia add to child care demand in the District. But we know that among the more than 270,000 Maryland residents and 176,000 Virginia residents who commute to D.C. for work, quite a few have children under age three—and some of these commuting parents prefer to use child care facilities near their workplaces in D.C.

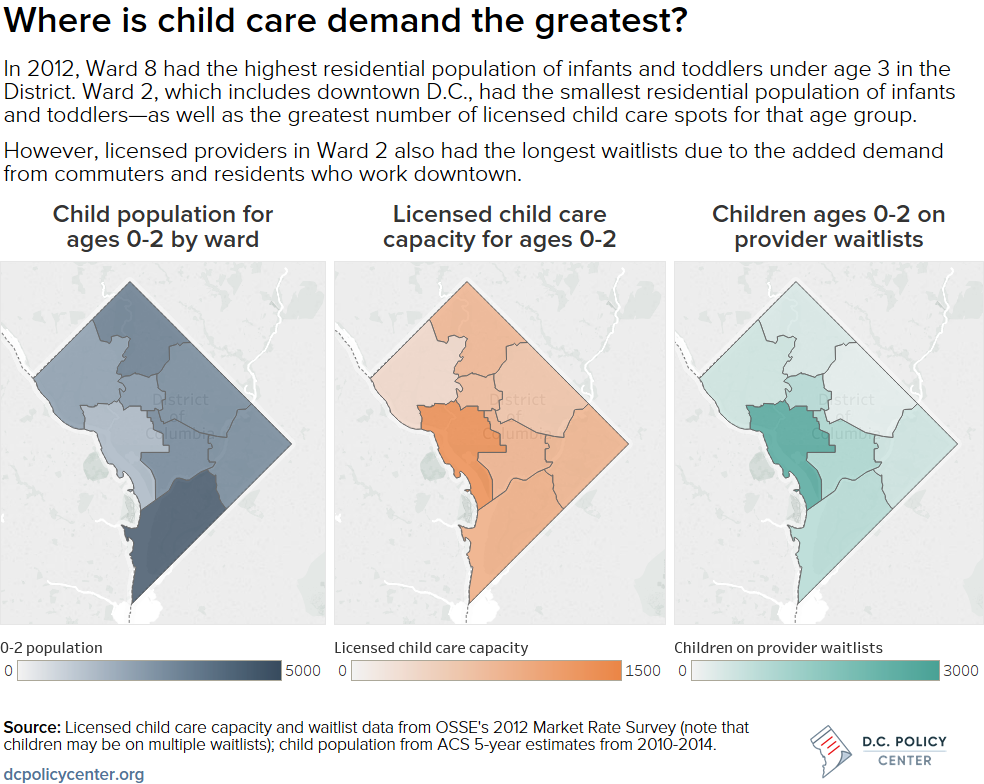

Looking at licensed child care supply and demand in Ward 2 is a useful example. D.C. Action for Children’s DC Kids Count Data Tools presents an excellent interactive map that shows how licensed care capacity for infants and toddlers in D.C. matches up to the number of children, broken down by neighborhood cluster. It’s an extremely useful resource, and makes use of the best data sources available. But it also shows just how much we don’t know about demand for child care in the context of the broader metropolitan region. For instance, licensed child care capacity for infants and toddlers is greatest along the central corridor of the District: in the north-central neighborhoods around Petworth, downtown, and in D.C.’s southernmost neighborhoods such as Congress Heights and Bellevue. After controlling for the number of infants and toddlers living in those areas, the central downtown neighborhoods still have the highest concentration of spots—with the area around Foggy Bottom boasting almost two licensed spots for every child under three.

But we also know that there is not exactly a surplus of licensed child care in downtown D.C. This is because our standard data sources can only tell us where children live—not where their parents work. When we look at the lengths of child care providers’ waitlists for infant and toddler spots (the most recent data on waitlists available is from 2012), we can start to see this missing demand from commuters and residents who work in the center of the District. Waitlists aren’t a perfect proxy for demand, but they are a useful indicator; as the maps below show, D.C.’s residential child population may be greatest in Ward 8, but its licensed child care capacity and provider waitlists are greatest in Ward 2, where its daytime worker population is concentrated.

Click here to explore an interactive version of these maps.

The preference to place a child with a provider near work versus home is a large factor at play, but not the only one. In addition, some parents may prefer home-based providers over larger centers, or vice versa. Other parents work irregular or nonstandard hours, and find very few licensed providers who are able to meet their scheduling needs. With all these factors influencing families’ decisions, it’s clear that we cannot fully estimate demand in a neighborhood or ward based only on the number of children living there.

Floods in a drought: When supply exceeds demand

In a typical market, a service-based business would follow its customers to areas where demand for its service is greatest (see, for instance, the recent boom in bars and restaurants along 14th Street). But the market for licensed childcare does not always work this way. In the case of licensed child care facilities, the high costs of starting a new location make it difficult for providers to quickly respond to existing geographical mismatches in licensed care supply and demand, even if they have information on changing demand patterns in the first place.

As a result of these and other factors, many licensed child care providers watch spots go unfilled even as others have months-long waitlists. In 2012, the last year that we have data available, there were 4,000 open child care slots for all ages across D.C., but 9,714 children—including 7,466 infants and toddlers—on provider waitlists.

Compounding the problem is an informational mismatch: There is no easy way for parents to identify which licensed child care providers have spots available at any given time. D.C. maintains a website that connects parents with lists of providers, but it contains no information about current openings or lengths of waitlists, let alone costs. Instead, parents must often contact each provider individually and apply for a spot, and hope that one becomes available when they are ready to use it. The Mayor’s proposed budget would help improve parents’ ability to search online for licensed care, but it is unclear if it will provide the up-to-date information about providers’ costs, quality, capacity, and waitlists that parents need when making child care decisions.

It’s worth noting that waitlists in themselves are not a bad thing. Studies have found that licensed child care providers in D.C. that serve infants and toddlers need to be operating at a very high level of capacity (almost full enrollment) in order to be profitable, and waitlists can help providers plan for future demand and ensure that they are running as efficiently as possible. The problem is in the length of the waitlist, and the unpredictability this presents for parents; parents returning to work may have very little flexibility in when they need care for their child, and months-long waitlists with uncertain outcomes only add to challenges of the child care search.

What we do know—and what remains to be studied

While the exact size of the child care gap is still unclear, we do know that the current system is placing a huge strain on families. Parents often must pay to put their child’s name on multiple waitlists, adding expense to the stress and uncertainty. Others may pay for unneeded care weeks before their child is ready to attend, just to secure a spot. Meanwhile, providers face many requirements and market constraints that prevent them from easily expanding their capacity, despite high demand. And when licensed care is too expensive or unavailable, some wealthier parents may turn to nanny-shares or other options, which are unregulated and of uneven quality. Meanwhile, lower-income families may have to turn to a patchwork of low-quality, unregulated care situations—or a parent (usually the mother) may drop out of the workforce altogether, risking long-term consequences to her career and the family’s economic outcomes.

There is already a lot of interest in working to better understand supply and demand in the District, including proposed legislation from Councilmembers and ongoing work from both the D.C. government and area nonprofits. This work should be able to answer the following questions: What are the economic, social, and logistical factors affecting how parents choose child care arrangements for infants and toddlers? When do families choose licensed care, and when do they choose informal, unregulated options? How do parents navigate the different types of care and subsidies available, and how do they understand their options? Where is there unused capacity that could be solved by increase efficiency, and where is the problem one of mismatched preferences, limited supply, or prohibitive costs?

Understanding the child care gap matters because how we define the problem determines the solution that we work toward. The next piece in this series will suggest other ways of thinking about our goals for child care and early childhood education, and suggest a framework for policy solutions going forward.