D.C. has expanded the way it evaluates developments’ impact on walkability. What does that mean, why does it matter, and how could the evaluation be even more nuanced?

Major real estate developments change the walkability of a neighborhood. Not only do new developments create new destinations that people walk to, they often include changes to sidewalks and intersections. Sometimes they include curb cuts for new garages, where cars come onto the sidewalk and block the flow of pedestrians. Sometimes they build new pathways letting people walk through the middle of a block, and sometimes they erect a building where people once walked on level ground. These changes have meaningful, quantifiable implications for mobility, economic performance, and equity, but for most of D.C.’s history they were not considered during the development approval process.

In June, the D.C. Department of Transportation published new guidelines for reviewing the transportation impacts of major real estate developments. These new guidelines may be the country’s most advanced in their attention to pedestrian infrastructure, but even they could be improved if they treated pedestrians with the same attentive, technical rigor that they use to treat traffic.

What is walkability?

D.C. is considered a highly walkable city within a highly walkable metropolitan area. Roughly 45 percent of D.C. residents commute entirely by walking (12.7 percent) or by public transportation (32.7 percent),[1] although the availability of transportation options varies greatly across the city. While larger structural elements, such as some level of density and car-free transportation options, are necessary for a city or neighborhood to be walkable, at the street level a person’s ability to walk to their destination is fragile. It can be hindered by obstacles like block-long detours, long waiting times at intersections, or narrow, uncomfortable sidewalks.

Walkability, then, is more than sidewalks. Academic researchers and city planners have found that comfort, safety, visual interest, connectivity, and directness of pathways are all necessary for a neighborhood to be walkable. Elements such as sidewalks, crosswalks, alleyways, plazas, and street furniture must not only be present, but cohere holistically into the “pedestrian realm.”

Traditional planning approaches often center cars in transportation evaluations, but D.C. is beginning to change that.

Whenever a major[2] real estate development proposal is submitted to the D.C. government for approval, the developer must provide a document called a Comprehensive Transportation Review (CTR) to the District Department of Transportation (DDOT). The CTR describes the impacts that the development would have on the city’s transportation infrastructure, and clarifies the measures that the developer will take to ensure that the impacts are beneficial rather than harmful. If DDOT does not approve the CTR, the development cannot be built – even if it has been approved by the Zoning Commission, Board of Zoning Adjustment, and every other relevant body.

A CTR is not a free-form document. Developers hire different transportation planning consultants, who prepare CTRs in different ways, but any CTR that hopes to be approved must follow the guidelines issued by DDOT. For decades, those guidelines had almost entirely been focused on implications for cars. CTRs were rarely more than traffic studies, measuring the impact a development might have on street parking or on delay times at intersections.

In June of 2019, DDOT released a new set of guidelines. It was the first change since 2012, when DDOT had first pioneered an element of pedestrian impact analysis – but the newest document goes much further in requiring developers to address their impacts on the pedestrian realm. It addresses two main concerns. First, the guidelines specify criteria for physical development. These criteria include parking maximums, sidewalk sizes, and a requirement to break down large blocks with pedestrian alleyways. Second, the guidelines include requirements for how to measure the impacts of development on pedestrians. Although the physical development criteria will have enormous implications for the city, this article will discuss the latter requirement – the question of how walkability is measured.

What Comprehensive Transportation Reviews (CTRs) generally cover

The District’s Interactive Zoning Information System provides copies of CTRs that have been submitted for historical and ongoing developments. A glance at these studies over the past seven years reveals that they focus much more on cars than on people. In a random sample of five recent PUD transportation studies they devoted an average of 27.4 pages to traffic and parking and only 4.6 pages to pedestrian infrastructure.

Those 27 pages about traffic generally follow the same model. A study begins by examining nearby streets as they currently exist, measuring capacity and congestion. Then it looks at the development itself, estimating the number of new daily trips that might be generated, and compares that prediction to an estimate of future congestion if the development isn’t built. If the development is likely to cause an unacceptable level of delay, the developer will propose measures like road-widening to relieve the congestion. This is the routine for traffic studies, and it’s followed by developers and planners across the country.

Although the 2012 guidelines did include language addressing walkability, it isn’t clear that developers always, or even usually, followed all the requirements. For example, those guidelines included the requirement that “Quantitative Data collection includes pedestrian counts at all intersections along primary pedestrian routes.” Like other requirements, this one was not followed in any of the approved CTRs that I read.

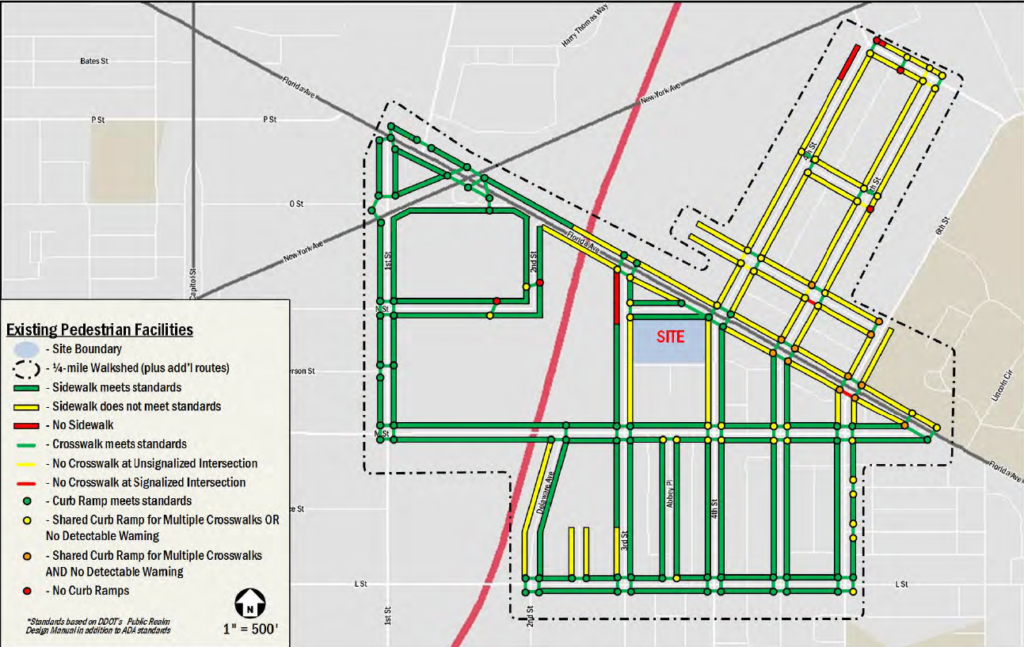

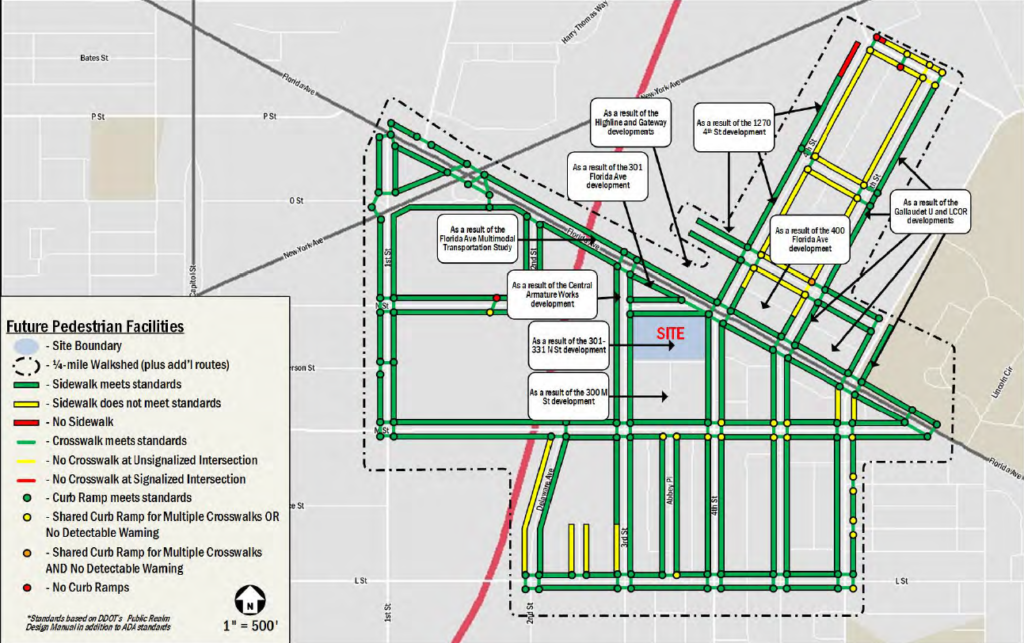

Some CTRs, though, included pedestrian infrastructure surveys. For example, the CTR for a development at 301-331 N St. NE compiled maps (below) showing the current state of pedestrian infrastructure in the blocks surrounding the development site and the predicted state of that infrastructure after the completion of the 301-331 N St. NE PUD and other proposed projects in its neighborhood.

However, even this relatively thorough coverage addressed pedestrian infrastructure only as a side-issue, rather than a critical element of the new development’s role in the neighborhood.

Existing pedestrian facilities diagram from the Gorove/Slade transportation study for the 301-331 N St. NE PUD

Existing pedestrian facilities diagram from the Gorove/Slade transportation study for the 301-331 N St. NE PUD

Future pedestrian facilities diagram from the Gorove/Slade transportation study for the 301-331 N St. NE PUD

Future pedestrian facilities diagram from the Gorove/Slade transportation study for the 301-331 N St. NE PUD

The 2019 CTR guidelines elevate pedestrian safety and walkability in transportation discussions

The new CTR guidelines represent a significant change, both from the status quo and from the official – though not necessarily followed – 2012 guidelines. They reaffirm the District’s commitment the MoveDC goal of having 75% of work trips by non-automobile modes. Some of the new walkability study requirements apply to the content of the transportation study, adding or replacing elements:

- Surveys of current and planned pedestrian infrastructure, like the one described for the project at 301-331 N St. NE, are now required for all CTRs – and are required to go into even greater detail.

- An inventory of street trees, which contribute in many ways to the pedestrian realm, is now required within a three-block radius of the project.

- An analysis of vehicle crashes has been replaced with an analysis of pedestrian safety.

- A count of pedestrians and a count of bicycles are now required at every intersection where a count of cars is required.

Other requirements apply to the way the study is conducted, making it more sensitive to pedestrians. For example, calculations for the predicted number of daily trips generated by the development, and for the division of those trips across modes of travel, are required to use up-to-date and locally-sensitive reference sources.

More can be done so that these guidelines can take in the full scope of pedestrians’ needs

While the new CTR guidelines enhance the content and method of the pedestrian impact analysis, there is still progress to be made in developing assessment methods that are sensitive to the variety of factors influencing walkability.

DDOT plans to continue to update the CTR guidelines on 12- to 18-month cycle, and has ambitious goals for the content it will cover. One of these goals is to “explore the use of new metrics and development of methodologies for quantitatively evaluating non-automobile modes of travel.” Fortunately, many such metrics and methodologies exist. Some of these techniques have been used elsewhere in the metropolitan area and others have been proven through their use in research.

Before diving into those specific metrics, it will help to understand why DDOT might not embrace a single-value walkability score. Such scores are powerful tools, and there are many ways that D.C. can use them productively, but they can never be fully context-sensitive. Even Walk Score, the most widely-used, turns out to correlate with economic activity more than actual pedestrian-friendliness. D.C. is home to a dazzling variety of urban neighborhoods. Any single-value walkability score will inevitably miss important details that a more in-depth, context-sensitive analysis will catch.

One area where the CTR guidelines have room for improvement is the count of actual pedestrian activity in the area surrounding the proposed development. The 2019 guidelines dictate that such a count takes place along with the survey of automobile traffic, meaning that it takes place during peak rush hours at intersections.

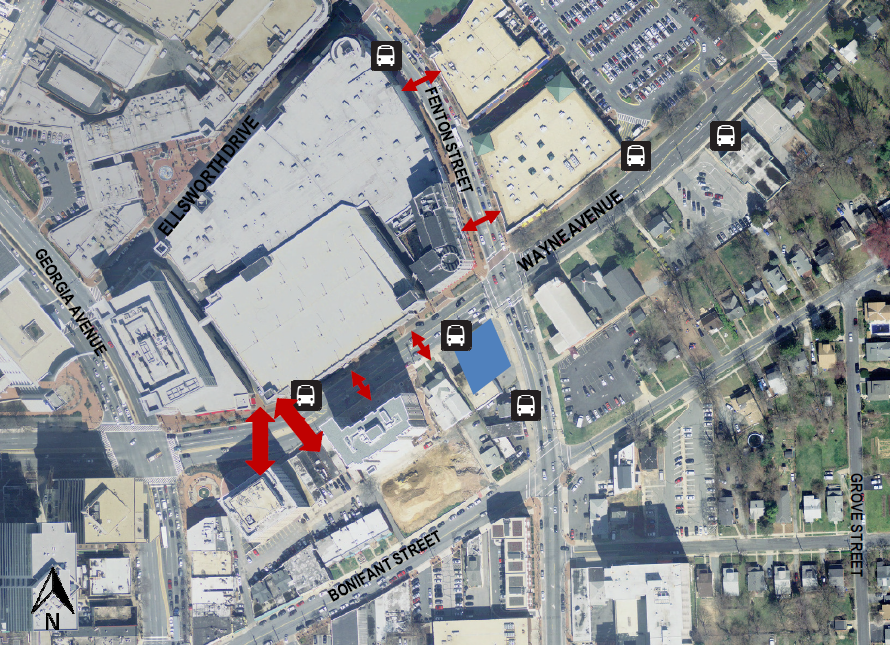

The problems of that approach become clear when we examine a study dedicated specifically to pedestrians. When Montgomery County rebuilt the Silver Spring branch of its public library system to include a platform for that light-rail line, it commissioned a study evaluating the impacts on walkability. That example illustrates two key approaches that could be included in a CTR.

First, like the pre-2019 existing pedestrian facilities assessment illustrated above, and like CTRs that follow the new guidelines, it contained a chart of existing pedestrian conditions. However, it differentiated between the actual width of a sidewalk and the effective width, as the latter might be lower “due to obstructions such as utility poles and overgrown vegetation.”

Second, as shown in the image below, the Montgomery County study notes the presence of “midblock pedestrian desire lines”—places where people frequently cross from one side of the street to the other without a crosswalk or signal. These places, where individuals have proven they will choose to risk danger in order to walk more directly, are hotspots in need of infrastructure safety improvements. However, because they are not at intersections, they will not be included in the traditional counting methodology required by the new CTR guidelines.

A third approach to a more nuanced assessment of pedestrian activity comes from the understanding that different modes of travel often experience different “peak hours.” Automobile travel usually peaks during the traditional nine-to-five rush hours. However, in downtown areas pedestrian travel often peaks during the lunch hour, and shows relatively high activity during evenings and weekends. The National Association of City Transportation Officials asserts that by measuring activity during peak hours, as the DDOT guidelines suggest, CTRs will overemphasize the role of cars in the transportation network.

Observed midblock pedestrian desire lines from the VHB Pedestrian Impact Statement for the Silver Spring Regional Library

We need to measure walkability outcomes with the same care and attention that we use to measure traffic outcomes

Aside from a more nuanced approach to pedestrian activity data collection, there are other techniques that could be included in a walkability impact study. I’ll close by discussing two of then—a connectivity assessment and a pedestrian intersection delay measurement—but there are many others.

Many development projects alter connectivity in the pedestrian network, either by creating or improving sidewalks or by creating new pedestrian passageways through the middle of a block. These alterations not only affect people walking from or to the development in question, they also affect people walking between many other locations in the neighborhood. The new CTR guidelines heavily emphasize the importance of such connectivity in their mandates for new alleyways and the reconnection of streets, but transportation planners could quantify that benefit by measuring the ped-shed for nearby origins and destinations as it would be both with and without the proposed improvement.

Intersection delay measurements are a mainstay of conventional car-focused traffic studies. Travelers spend much of their travel time waiting at intersections, whether for a green light or a pedestrian signal. However, while the world of transportation engineers has developed an array of technocratic tools for measuring the delay experienced by cars, there seems to be no standardized way of measuring the delay experienced by pedestrians. At some intersections—particularly intersections where drivers enjoy dedicated turning arrows—pedestrians often must wait disproportionately long before they can cross. Approaches to measuring pedestrian delay at signalized intersections have seen some academic validation, but DDOT may have an opportunity to further its reputation as a national leader by pioneering this technique at the municipal level.

D.C officials, planners, and councilmembers are increasingly turning their attention to how the District can make streets safer for everyone who moves around the city, whether by foot, bike, or vehicle. But in the negotiations that determine the future of our built environment, cars and their infrastructure are still given a disproportionate share of the attention. As it shapes the many conversations that will, in turn, shape our city, the District Department of Transportation has recently seized an opportunity to center the needs of pedestrians in transportation planning conversations. Many more opportunities still await.

Feature photo by Ted Eytan (Source)

Taylor Reich (they/them) is a native Arlingtonian. Though they are a research associate at the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, where they work to improve indicators for measuring sustainable mobility in developing cities, this article is not affiliated with ITDP in any way. See their website for more of their work.

Notes

[1] Source: Commuting characteristics for workers ages 16 and older in D.C. (S0801), American Community Survey 1-year estimates for 2017.

[2] Transportation review is not required for every new construction project in the District. Small projects, those that will generate fewer than 25 new car trips during rush hour, are generally exempt.