This article is adapted from “Teachable Moment: ‘Blockbusting’ and Racial Turnover in Mid-Century D.C.,” which originally appeared in Washington History, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Fall 2018), published by the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., and is reprinted and adapted with permission. Many of the documents discussed in this article can be viewed at Mapping Segregation in Washington DC.

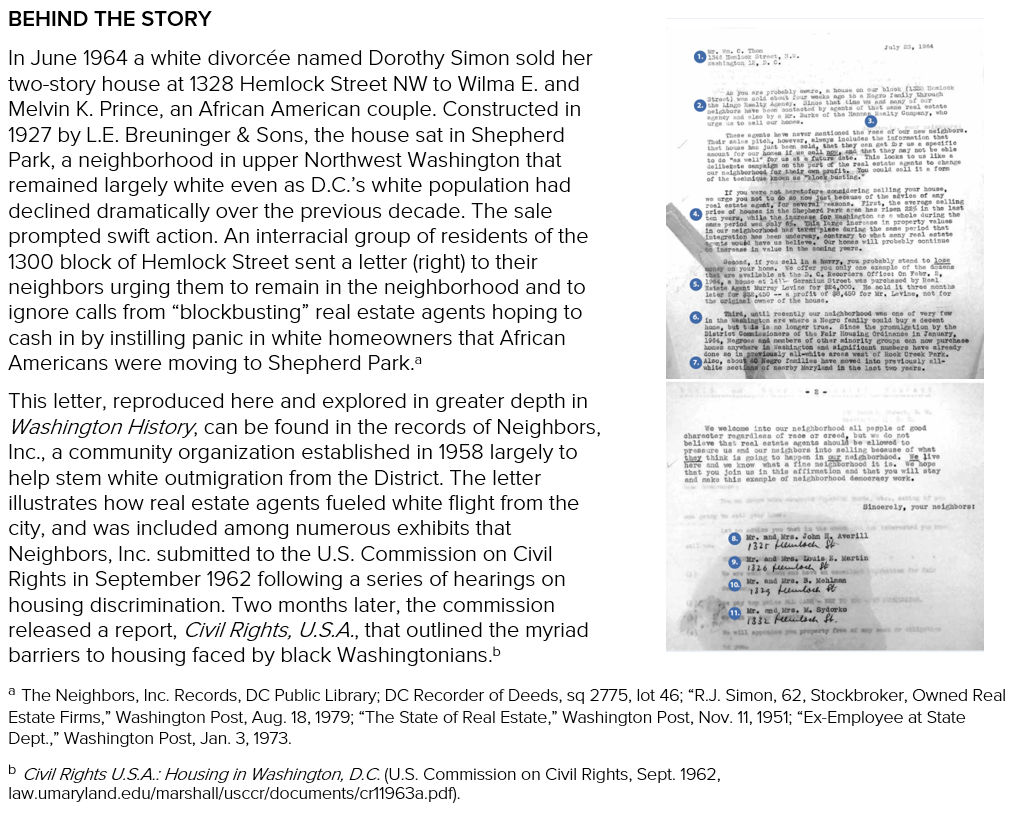

For the first half of the 20th century in much of Washington, D.C.—especially north of Florida Avenue and east of the Anacostia River—racially restrictive deed covenants legally barred black settlement. They served as both a legal mechanism for enforcing residential segregation and as a signifier of property values; covenants were the outgrowth of a science of real estate that emerged in the early 1900s and assigned value to houses and whole neighborhoods according to the race of their occupants.[1] (For more on the history of racial covenants in D.C., see “The rise and demise of racially restrictive covenants in Bloomingdale.”) By the time the Supreme Court ruled in Hurd v. Hodge (1948) that enforcing such covenants was unconstitutional, the association of race with property values was inextricable, and real estate brokers used it to their advantage. “Blockbusting is an offspring of restricted occupancy,” noted the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, in September 1962. “The blockbuster enters a white area, sells a few homes to Negroes, and then stimulates panic selling by other residents. He relies upon underlying racial prejudice which he intensifies and distorts for his own use. . . . Homeowners have been assailed with junk mail, phone calls and door-to-door solicitations asking them to sell.”[2]

Because racial covenants had long constricted the housing supply in a city with a substantial black middle class (housing in Shepherd Park and the rest of today’s Ward 4 was almost entirely off-limits to black buyers until 1948), real estate agents stood to clear huge profits in selling to African Americans. Pent-up demand led black homebuyers to pay artificially high prices. One couple told the Washington Post in 1962 that they had purchased their “dream house” in Shepherd Park, which they described as “built for white people,” but later discovered they had been overcharged about $2,000. “At another house,” the article reported, “a white neighbor overheard the agent jacking the price by that amount to a Negro prospect.”[3] As a result—and because integrated neighborhoods were so rare, reported the Post in 1969—home values in Shepherd Park increased significantly in the period most associated with white flight from the District.[4]

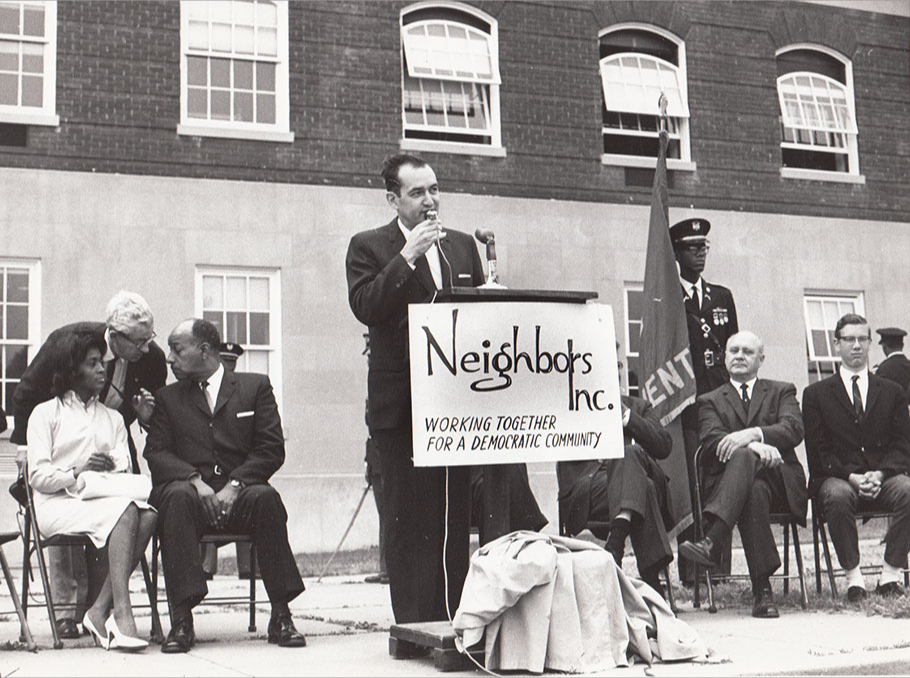

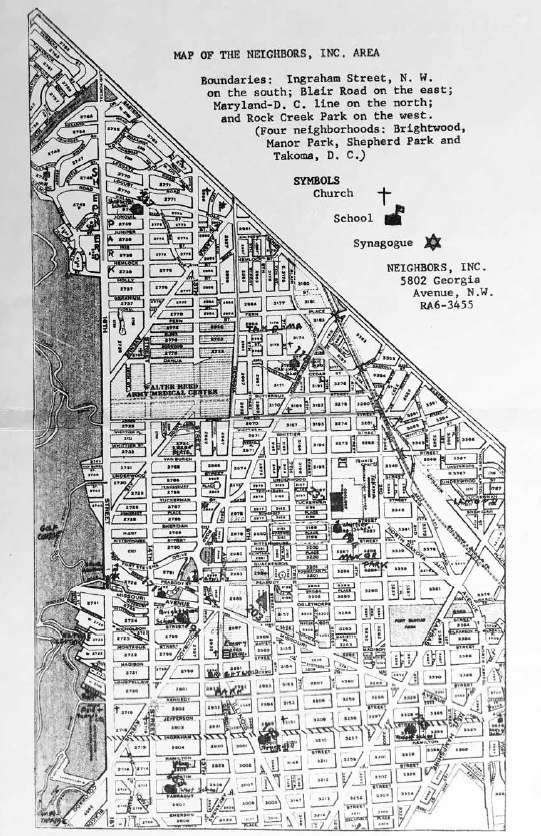

Neighbors, Inc. was founded in 1958 by an interracial group of Manor Park residents after their neighborhood citizens association refused to admit black members. It opposed blockbusting and sought to foster stable, integrated, middle-class neighborhoods, with a focus on the area east of Rock Creek Park and north of Missouri Avenue. Courtesy DC Public Library, Washingtoniana Division, Neighbors Inc. Records. (Mapping Segregation in Washington DC)

Founded in 1958 by an interracial group of Manor Park residents after their neighborhood citizens association refused to admit black members, Neighbors, Inc. opposed blockbusting and sought to foster stable, integrated, middle-class neighborhoods, with a focus on the area east of Rock Creek Park and north of Missouri Avenue. Neighbors, Inc. established a Housing Information Service that worked especially to attract white home-seekers to neighborhoods where the group was active. The organization was credited with bringing “60 or more white families” to Shepherd Park in 1960-1963, a period when white residence District-wide was in significant decline.[5] It challenged racially discriminatory lending and real estate practices through education. It also collected evidence of racial steering. A February 1959 eviction notice to white tenants in Petworth, for example, explained that, “in view of the nature of the neighborhood . . . the owner has decided to convert the building to colored occupancy.” A white couple reported that an agent refused to show them a house in predominantly black Adams Morgan. White homeowners in Columbia Heights, Takoma, and Woodridge documented the rejection of loan applications on the grounds that the neighborhoods were declining in value due to racial change.[6]

This undated map shows the original boundaries of Neighbors, Inc.’s work. Courtesy DC Public Library, Washingtoniana Division (Mapping Segregation in Washington DC)

This undated map shows the original boundaries of Neighbors, Inc.’s work. Courtesy DC Public Library, Washingtoniana Division (Mapping Segregation in Washington DC)

Neighbors, Inc., was one among several D.C.-area organizations that promoted integrated neighborhoods and advocated for changes in housing policy, including Northwest Washington Fair Housing, Suburban Maryland Fair Housing, Prince George’s County Fair Housing, and Northern Virginia Fair Housing. The American Friends Service Committee reported in 1964 that thanks to its partnership with these groups, “between 35 and 40 minority group families were able to buy or rent suburban homes between January and July.”[7] Established social justice organizations such as the NAACP, CORE, the Washington Urban League, the American Veterans Committee, the AFL-CIO, and others also demanded black access to housing and opposed policies that would lead to resegregation.

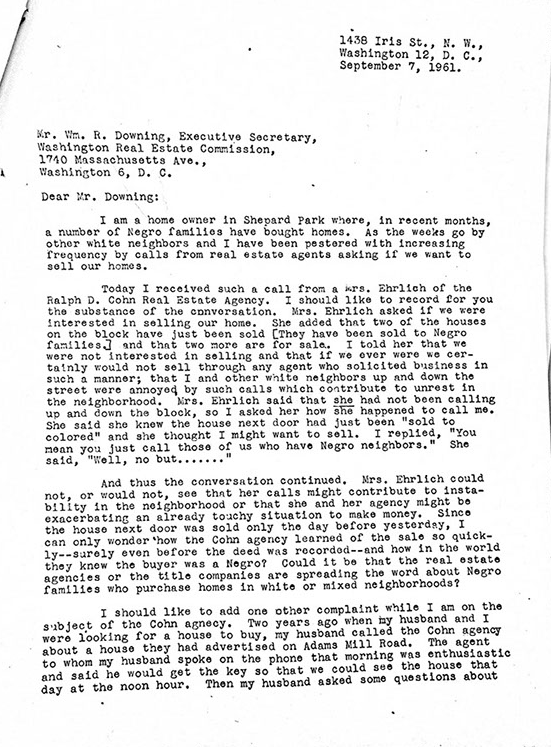

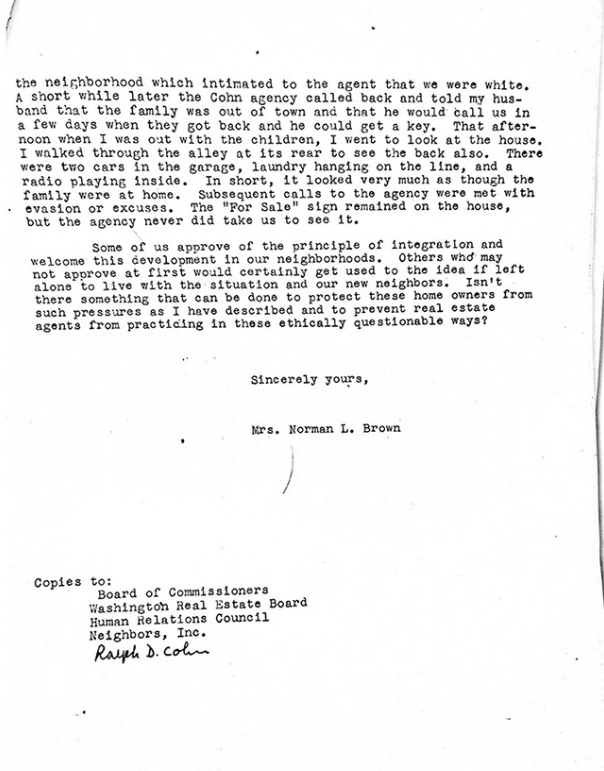

A white Shepard Park resident’s letter to the Washington Real Estate Commission describes an inquiry she received from a real estate agent just after a black family moved in next door. She also mentions her husband’s earlier effort to visit a house in Adams Morgan that the same agency had advertised but refused to show to a white client. Courtesy DC Public Library, Washingtoniana Division (Mapping Segregation in Washington DC)

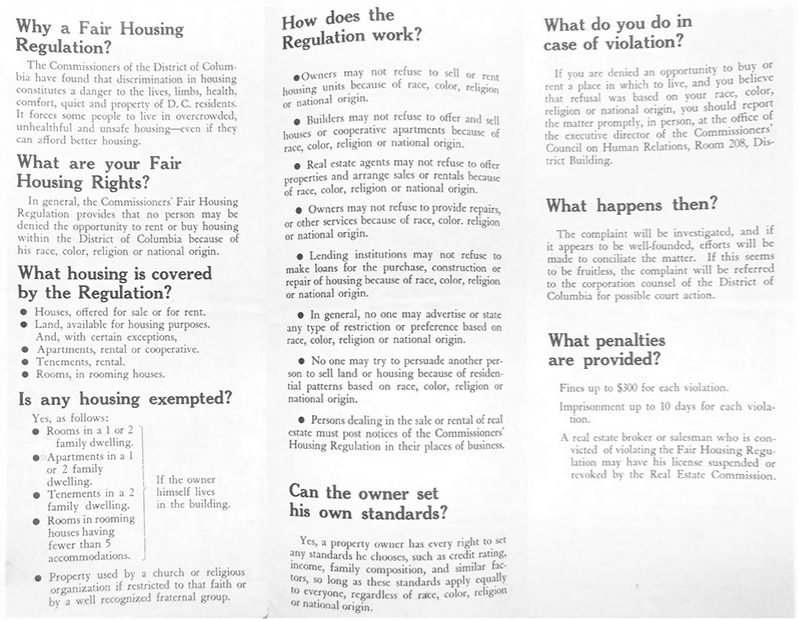

The impact of Neighbors, Inc., and other groups was initially hampered by the D.C.’s lack of any policies prohibiting discrimination until 1964. As of 1960, all but 2.2 percent of new houses in the metro area and more than 90 percent of new rental units had conveyed only to white residents during the previous decade.[8] Once the new regulations took effect in January 1964, the ordinance was poorly enforced, and without similar legislation in surrounding jurisdictions, the impact of the fair housing groups was limited. In the nine months after the D.C. law took effect, Neighbors, Inc. documented ongoing discrimination. Real estate agents withdrew houses from the market, quoted higher, non-negotiable prices to black home-seekers, and required black buyers to offer contracts with “no conditions whatever”—not even the customary termite and financing clauses. Some notified lenders that their clients were black, resulting in difficulties qualifying for a mortgage and worse credit terms. Some refused to submit bids for black clients, or to inform them of counter-bids. Some placed newspaper ads for the purpose of racial screening (showing black clients houses that differed from those advertised). Agents also sold unlisted properties to white buyers while telling prospective black clients they had nothing available, and refused to share listings with agents who took black clients.[9]

At this time, neighboring Montgomery County, Maryland, had no fair housing law and many longtime black county residents had been pushed into the District as racially restricted subdivisions were built. As a result, in 1960, 90 percent of D.C.-area suburbanites lived in census tracts that were 90 percent white. Although many black Washingtonians eventually were able to buy homes in Prince George’s County, Maryland, the suburbs would remain largely off-limits to African Americans even after the federal Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968.

Your Fair Housing Rights: A quick guide to the District Commissioners’ Fair Housing Regulation (brochure). D.C.’s fair housing law took effect on January 20, 1964, and the first complaint was filed five days later. By November 1964, the number of complaints filed in D.C. (110) was second only to the number filed in New York. Courtesy DC Public Library, Washingtoniana Division (Mapping Segregation in Washington DC)

Ongoing white resistance also undermined efforts to promote integrated neighborhoods. Not all white residents who lived in areas served by Neighbors, Inc. welcomed African Americans. Mignon Wilson—whose husband directed a center for foreign students at Howard University—remarked of the white neighbors on her block in Manor Park that “one hardly speaks [to me] and the other never does. My block is integrated, but what does this mean?” Unwilling to confront racism, many black families chose not to move to historically white areas. Sociologist George Grier testified to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission that he had frequently been told, “I don’t want to pioneer. I want a nice house and a pleasant neighborhood, but I don’t care to break any racial barriers in doing it. I just want to be left alone. I want to be in peace. I don’t want my children to be hurt.”[10]

Yet many residents in integrated neighborhoods—especially those who joined Neighbors, Inc.—bonded cross-racially over shared backgrounds and interests. “All of us have about the same educational background, and our children play together,” said one black resident of Manor Park in July 1964. Neighbors, Inc. co-founder Marvin Caplan later confirmed, with some regret for the group’s behavior toward less desirable neighbors, that “class homogeneity helped keep us together.” Neighbors, Inc.’s mission also inadvertently reinforced the valuation of neighborhoods by racial makeup, with the underlying assumption that an area would decline if it became too black. Nevertheless, Shepherd Park and Takoma were the only neighborhoods within Neighbors, Inc.’s original boundaries that remained more than 30 percent white in 1983. In fact, Shepherd Park Elementary was the only school in the area to remain integrated; most white families sent their children to out-of-boundary or private schools, especially for middle and high school.[11]

To explore this letter, see “Teachable Moment: ‘Blockbusting’ and Racial Turnover in Mid-Century D.C.” in Vol. 30, No. 2 (Fall 2018) of Washington History, the magazine of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C.

These documents and others collected by Neighbors, Inc. counter a standard narrative of mid-century white flight as fueled almost entirely by the desegregation of D.C.’s schools, ensuing disinvestment, and the events of 1968. White outmigration was largely driven by the active reinforcement of race as a tool for predicting the future value of property. With real estate as an increasingly powerful driver of public policy in D.C., its historic and continued role in shaping D.C.’s racial landscape must not be overlooked.

Sarah Jane Shoenfeld is a principal of Prologue DC, LLC, and a co-director of the public history project Mapping Segregation in Washington DC. The DC Preservation League, Humanities DC, and the National Park Service (Historic Preservation Fund) supported this research as a component of that project, but the opinions expressed in this article belong to solely to the author.

Notes

[1] One covenant stated “that only one house, to be detached, to cost not less than $10,000 to build, and to be not less than Two (2) full stories in height, shall be erected on said lot.” Prior to residential zoning, such covenants dictated the density as well as the size and cost of housing in developing neighborhoods.

[2] Civil Rights U.S.A./ Housing in Washington, D.C. (U.S. Commission on Civil Rights), Sep., 1962, 13.

[3] Stephen S. Rosenfeld, “Interracial Group Tries to Make Living Easier in Changing NW Neighborhood,” Washington Post, Jan. 18, 1962.

[4] Shepherd Park resembled other middle class urban neighborhoods that saw values remain stable or go up during this period. A 1960 seven-city study frequently cited by Neighbors, Inc. and other neighborhood “stabilization” groups showed that over the previous 12 years, integration in areas comprised primarily of single-family housing had frequently led to increased property values. Susan Jacoby, “D.C. Only for Rich and Poor,” Washington Post, June 1, 1969; Luigi Laurenti, Property Values and Race (Berkeley: U. of California Press, 1960). See also, “An Economic Analysis of Property Values and Race (Laurenti),” Land Economics, 1960, 183-86; Phyllis Palmer, Living as Equals: How Three White Communities Struggled to Make Interracial Connections during the Civil Rights Era (Nashville: Vanderbilt U. Press, 2008), 107.

[5] Draft of article submitted to the National Capital Area Realtor in early 1964, Racially Mixed Housing Articles (1963), Box 11, Neighbors, Inc. Records, DC Public Library.

[6] Additional evidence of racial steering collected by Neighbors, Inc. include a letter to a white Mount Pleasant homeowner listing suburban properties available for sale; a memo from a white newcomer to Crestwood who complained of being warned by Realtor Paul Stone that an influx of “colored” children into the neighborhood schools was causing property values to plummet; and testimony by a white couple that their landlord had twice increased the rent on their Kennedy Street NW apartment, without making improvements, in a deliberate effort to clear the building for black renters. (The couple then moved to Silver Spring, Maryland.) Marvin Caplan, Farther Along: A Civil Rights Memoir (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999), 161-63; Real Estate Report of Activities (1959-1962), Box 11, Neighbors, Inc. Records.

[7] “‘Fair Housing’ Groups Breach Racial Barriers in More Communities,” Wall Street Journal, Oct. 8, 1964.

[8] Civil Rights U.S.A., 2-3.

[9] Interim Working Paper, Sept. 30, 1964, Fair Housing, General (1955–1964), Box 11, Neighbors, Inc. Records.

[10] Civil Rights U.S.A., 7. A Chevy Chase fair housing group could find hardly anyone to assist with home-buying, and in January 1965, the Washington Post reported that a total of just twelve black families had moved there during the previous year. Kay Roberts, “Negroes Sought for Chevy Chase,” The Evening Star, June 19, 1964; See also, “Colored families break D.C. ‘noose’ and move to suburbs,” Washington Afro-American, Aug. 24, 1963.

[11] Susanna McBee, “Integrated Neighborhood Loses Self-Consciousness about Race,” Washington Post, July 17, 1964; Caplan, Farther Along, 173; Jim Bryant, “Neighbors Inc., at 25, Still Tackles Local Problems,” Washington Post, June 29, 1983.

Feature photo courtesy DC Public Library, Washingtoniana Division, Neighbors Inc. Records.