With a pang of nostalgia, in my previous article I called attention to “all the high-rise apartments and condominiums that have sprung up in NoMA in the past two decades.”

More than a half century ago I worked in that very neighborhood long before NoMa was ever imagined by city planners and developers.

I first came to the neighborhood as a low-level volunteer organizer of the great March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. Working out of the Washington Urban League’s offices near the corner of Third and G Streets, NW, I remember hanging out the window, counting chartered buses roaring past in police-escorted caravans down Third Street … first, by the dozen … then, by the score … ultimately, by the hundreds – a thrilling sight. After the March, I joined the Urban League staff for the next five years.

NoMa’s Roots: Fighting Poverty

Our office was not just located in the future NoMa neighborhood. Under the New York Avenue NW, North Capitol Street, Constitution Avenue (though effectively E Street, NW), and 5th Street NW. Massachusetts Avenue NW bisected the neighborhood as did New Jersey NW, angling from southeast to northwest.

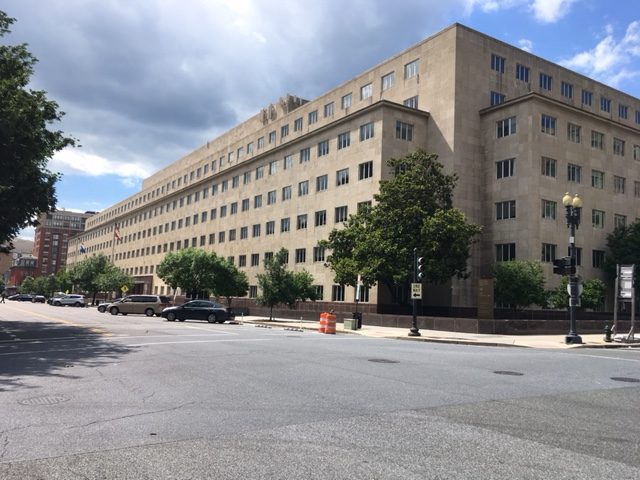

The neighborhood sat on the fringes of official Washington. Judiciary Square was on the western edge and the giant, 1950s-style General Accounting Office was just as ugly a half century ago (when it was relatively new) as it is today. Still drawn to “modernity,” I really never appreciated its red-brick neighbor, the post-Civil War Pension Building.

The GAO Building, which nearly spans 2 million sq. ft., and has over 1,000 windows. Photo by David Rusk.

But the neighborhood was primarily home to people–per the 1970 census, 5,339 persons in 2,017 homes (mostly rentals)–86 percent black, typical family income less than half D.C.’s median, and over half poor (52 percent by the then newly-defined federal poverty standard).

Red-brick two-, three-, and four-story row houses lined the elm tree-shaded streets. Many were badly maintained and carved up by slumlords into as many units as they could get away with. Our mission was to help the neighbors organize community action targeting bad landlords and unresponsive District bureaucrats.

So many memories, such as –

- Evening meetings with block clubs like the 900 New Jersey Avenue Block Club or the Defrees Street Improvement Association.

A 2-story parking lot on New Jersey Avenue, perhaps held for future development, as seen in the background. Photo by David Rusk.

- Grabbing a quick lunch at the counter of our local greasy spoon at Third & F Streets NW–whatever its formal name, known universally as “Buffo’s.”

- Soon after enactment of the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act of 1966, our tent city sprung up on weed-strewn vacant land near New York Avenue, NW to protest the District’s foot-dragging on building long-promised public housing there. The banner: “The USA’s First Demonstration City!” (Within a week the White House rechristened its new initiative the “Model Cities Program.”)

- Commandeering a closed-for-the summer Lincoln Junior High School at First and M Street NW for two days as an induction center for 1,100 black teenage boys hired by Pride, Inc. in August 1967.

Perry School at First and M Street NW, formerly Lincoln Junior High School. Photo by David Rusk.

- Running a Rumor Control Center, dispelling wild rumors and directing D.C. residents where to turn for help as fires raged just four blocks over on Seventh Street NW amid the rioting after Dr. King’s murder in April 1968.

NoMa Today – Two Worlds Side-By-Side

A half century later, it’s almost all gone except the massive Government Printing Office, DCFD Engine #1 Firehouse, and churches–Holy Rosary Church (with its Casa Italiana), Mt. Airy Baptist, the imposing Bible Way Temple (founded by Bishop Smallwood Williams in my day), and a scattering of others.

Plus, Gonzaga College High School is still at North Capitol and K Streets, NW, but Defrees Street has disappeared completely, vanished under Gonzaga’s turfed sports field (with a new Walmart nearby). Thankfully, the Pension Building has a new life as the National Building Museum but the General Accountability Administration’s monstrosity is still with us.

Gonzaga’s athletic field, which has swallowed up the Defrees Street. New development all around. Photo by David Rusk.

The Urban League and Buffo’s? Vanished under a new office building. The row houses and apartments? Basically, all below Massachusetts Avenue are gone, torn down for office buildings, the Georgetown Law Center, and new hotels – The Hyatt Regency, the Washington Court, and the slyly-named The Liaison Capitol Hill.

Buffo’s and Urban League buildings have been replaced by this building. Photo by David Rusk.

Much low-income housing did get built, including the city-owned Sibley Plaza and Sursum Corda projects plus tenant-owned, 199-unit Sursum Corda Cooperative on the site of “the USA’s First Demonstration City.” But dominating new construction are high-rise apartments and condominiums flanking Massachusetts Avenue.

The result has been a demographic transformation. By 2015, the old neighborhood’s population had almost doubled to 9,918 in 5,159 housing units – two and a half times the number of units 45 years before. The new residents are primarily young professionals and empty nesters – in the census tracts flanking Massachusetts Avenue, 62 percent white and Asian, a 14 percent poverty rate, but median household income one-third above the District median and five percent above the metro area median.

The northern part of the neighborhood (the triangle formed by New York Avenue, NW, North Capitol Street, and K Street, NW) is still predominately black (69 percent) and, with so much public housing, many poor (24 percent). Median household income is barely one-third D.C.’s median and only one-quarter that of the gentrified southern two-thirds of the neighborhood.

And the gentrification beat goes on.

After the substantial failure of the District-initiated Northwest One project, in August 2015 Sursum Corda Cooperative Association announced a partnership with Winn Development Co. and adjacent private landowners in the neighborhood to redevelop the Sursum Corda co-op and the surrounding 6.7 acres of land into a new high-density, mixed use housing development. The development will contain more than 1,100 apartments, 41,000 square feet of retail space, and 800 parking spaces. Two buildings on the site of the current Sursum Corda Co-operative Apartments will contain 339 units and 373 units – two and a half times its current capacity.

What happened to all the neighbors whom the Urban League worked with in the mid-sixties? Some of the better-off probably moved into the Sursum Corda Co-operative. Others, into Bible Way Temple’s Golden Rule Apartments or into the public housing projects also built near New York Avenue. Most of those relocated probably moved into public housing elsewhere in the District, or, very often into Prince George’s County. Hopefully, most movers found better opportunities to transform their lives than staying in the old neighborhood.

But from today’s vantage point the 1960’s-era neighborhood is now a house divided – two separate worlds, one largely white and high income, the other largely black and low-income.