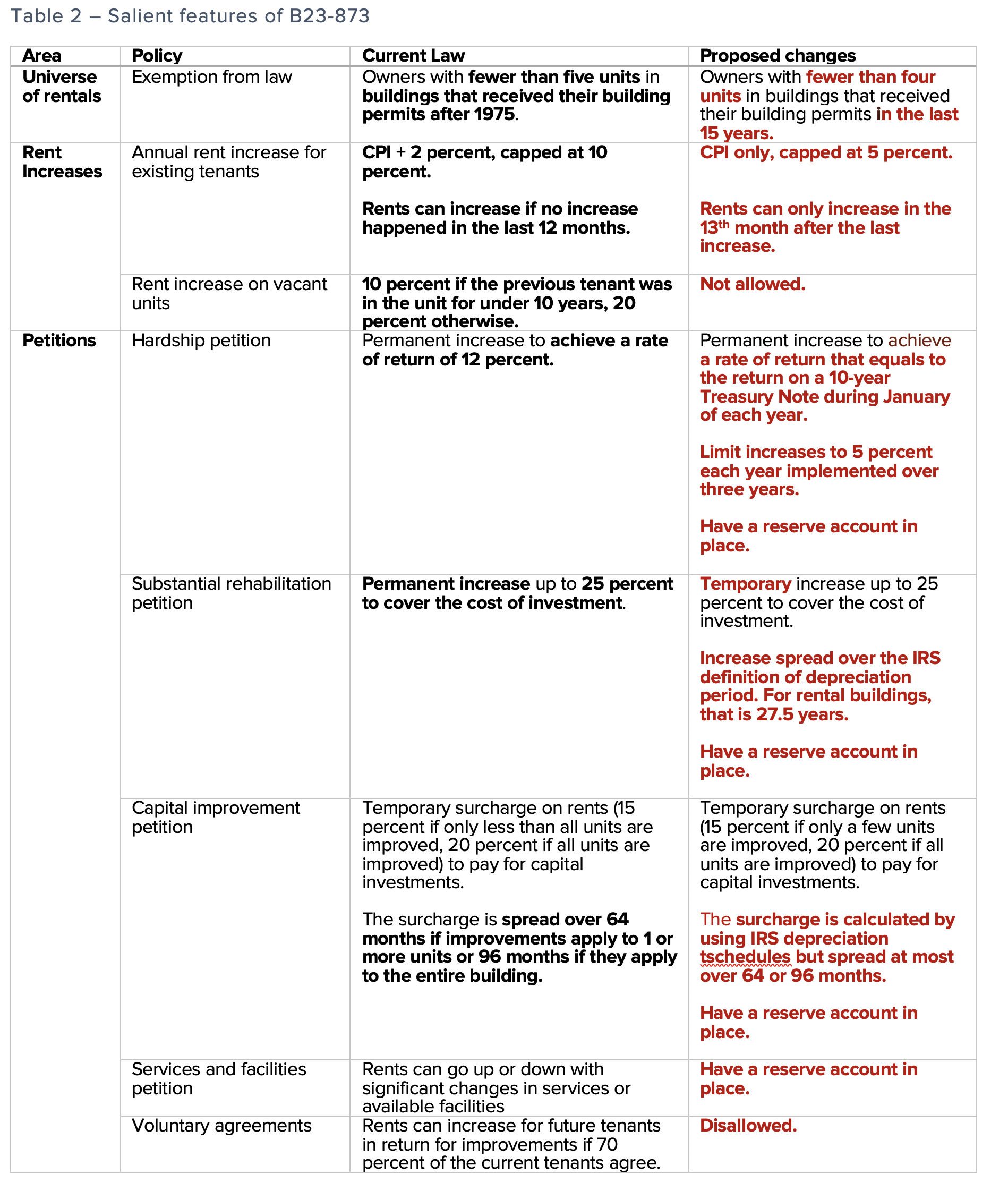

Bill 23-873, the Rent Stabilization Program Reform and Expansion Amendment Act of 2020 would make comprehensive and sweeping changes to the current rent control laws, affecting every aspect including the universe of rent-controlled units, calculation and timing of rent increases including increases on vacant units, and various petition processes.

Changes to exemptions

Bill 23-873 would expand the universe of rent-controlled units in two ways. First, it would create a dynamic rent-controlled stock by limiting exemptions to units in buildings that received their building permits in the last fifteen years.[1] For example, if the bill were to be implemented this year, the exemptions would apply to units in buildings that received their building permits after January 1, 2005. And with each passing year, the exemption threshold would move up one calendar year.

Second, the bill would limit the exemptions to landlords with fewer than four units in multifamily buildings, subjecting even smaller landlords to rent control.[2] At present, landlords with fewer than five units are exempted.

Changes to rent increases

Bill 23-873 would limit annual rent increases for existing tenants to the growth in Consumer Price Index (CPI), capping this increase at 5 percent at most.[3] Current law allows for CPI+2 percent, and the allowable rent increase is capped at 10 percent regardless of the growth in CPI.

The bill would also restrict the time window a landlord can implement a rent increase to the 30-day period after the anniversary of the last increase.[4] At present, rents can increase if no increase happened in the last 12 months. That is, if a housing provider last increased rents in February 1 of 2019, rent can increase any time after February 1, 2020 (but won’t be allowed to increase again for 12 months after that next increase). Using this example, B23-873 would require providers to implement a rent increase between February 1, 2020 and March 1, 2020 only; and if a provider forgoes that increase during the 30-day period, the provider would not be allowed to increase rents until February 1 of 2021.

Bill 23-873 would also do away with vacancy increases.[5] At present, when a unit is vacated by the current tenant, its rent for the next tenant can increase by up to 20 percent if the previous tenant occupied the unit for more than 10 years and by up to 10 percent otherwise. This provision of the District’s rent-control laws is the key indicator that the laws are designed to provide price stability for the existing tenants, and not deliver rents that are significantly below-market for new tenants. Eliminating vacancy increases means that rents would be allowed to grow by CPI only, and at most by 5 percent.

Changes to the petition process

Bill 23-873 would change various provisions for the hardship, substantial rehabilitation, and capital improvement petitions, and would disallow voluntary agreements. The bill proposes many changes to these petition processes; we summarize below the most salient changes.

The bill changes the allowable rate of return for hardship petitions from 12 percent to the rate of return that equals to the return on a 10-year Treasury Note during January of each year.[6] In January of 2020, this return was equal to 1.76 percent. Additionally, regardless of the actual increases allowed under a hardship petition, actual annual increases would be capped at 5 percent annually, and implemented over a period of no longer than 3 years.[7]

Bill 23-873 would also make rent increases allowed under a substantial improvement petition only temporary[8] and would require that the housing provider recover the cost of the improvements over the depreciation period, which, under current IRS rules, is 27.5 years for rental buildings. At present, rent increases allowed under a substantial improvement petition are permanent.

Bill 23-873 would require that when filing capital improvement petitions (improvements that cost less than half the appraised value of a rental apartment building), housing providers use the IRS depreciation schedules to calculate the allowable surcharges they request to support the capital improvements. But the bill leaves in place the 64-month and 96-month surcharge periods, which means that for capital investments with a longer depreciation period, the provider would not be able to recoup the entire cost of the investment.[9] At present, providers can spread the full allowable cost over the prescribed period and do not have to use IRS depreciation guidelines.

For all petition processes, B23-873 would require that housing providers have in place a replacement reserve account.[10]Providers would be required to deposit in this account $250 per unit each year beginning with the adoption of the bill, and this amount would be required to increase by CPI each year. A housing provider would not be allowed to use any of the petition processes until such a reserve is in place and holds at least three years’ worth of deposits in it.

Finally, B23-873 would disallow voluntary agreements.[11]

<< Back: Main publication page | Next: Impacts on the rent-controlled stock>>

Notes

[1] By amending D.C.OfficialCode§42-3502.05(a)(2).

[2] By amending D.C.OfficialCode§42-3502.05(a)(3).

[3] By amending D.C. Official Code § 42-3502.08(h).

[4] By amending D.C. Official Code § 42-3502.08(g).

[5] By amending D.C. Official Code § 42-3502.08(h) and repealing D.C. Official Code § 42-3502.13.

[6] By adding a new definition under D.C. Official Code § 42-3501.03.

[7] By adding a new subsection under D.C. Official Code § 42-3502.12.

[8] By adding a new subsection under D.C. Official Code § 42-3502.14.

[9] By amending D.C. Official Code § 42-3502.10.

[10] By adding a new section under D.C. Official Code § 42-3502.

[11] By repealing D.C. Official Code § 42-3502.15.