The District of Columbia is becoming increasingly more segregated by race and income in many areas. As outlined in the Urban Institute report The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital, this segregation is built on racist public and private practices, and has amplified disparities and inequities in health, education, and work opportunities, with effects that continue today.

Built on this foundation, the city’s current lack of affordable housing has contributed to the displacement of longtime low-income residents of color. In a recent study, D.C. Policy Center Executive Director Yesim Sayin Taylor wrote:

“Housing policies are central to the inclusiveness of a city. Housing defines, in large part, how residents share the wealth created by a city and how they access its assets and amenities. Where we live deeply affects our quality of life and the opportunities available to us and our children, especially jobs and better schools. How we invest in a neighborhood determines the desirability of the housing stock in that neighborhood and how we regulate our housing markets can shape who stays in the city and who leaves. Public policies that control the housing supply and public investments in amenities and services such as schools, transportation, and infrastructure can play roles equally strong as private wealth in defining the demographic make-up of a city. Population growth and demographic changes continually play out through the housing market, and when housing is constrained, these forces further amplify gentrification, economic segregation, and displacement.”

In partnership with the Consumer Health Foundation and the Meyer Foundation, the D.C. Policy Center asked a cross-section of community organizations, traditional and low-income housing developers, researchers, and other stakeholders to answer the question: What is the most important public policy that could increase affordable housing, reduce housing inequities, and create a more inclusive D.C.? What is the biggest obstacle to implementing your desired policy, and how can it be overcome?

The responses we received are fascinating and wide-ranging. Several respondents identified key aspects of current housing policy that can be strengthened, improved, or otherwise utilized more effectively. For instance, Peter Tatian and Mychal Cohen of the Urban Institute propose creating a tax on luxury homes that could be used to expand rent subsidies, while Claire Zippel of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute suggests a range of solutions to help the city realize the potential of housing vouchers to reduce segregation. Thomas Borger of Borger Management suggests reexaminations of existing tools such as rent control, while Chris Smith of WC Smith proposes renewed attention to range of options, from expanding housing voucher access to evaluating the opportunities in city-owned land. Catherine Lampi and Fernando Lemos of Mi Casa also argue for increased public investment in long-term housing sustainability through expanding limited-equity cooperatives and requiring 40-year affordability covenants.

Some respondents offer opposing views on certain topics, such as the role of new development in causing or ameliorating the city’s gentrification pressures, but there were also frequent points of agreement on the need for strategies that drive the returns of home ownership back into local communities. Dominic Moulden (ONE DC) and Amanda Huron (UDC)—among others—highlight the possibilities of community land-trusts and limited equity co-ops as strategies to prevent displacement in the face of gentrification and rising housing prices. In addition to these community-based strategies, Joshua Bernstein of the Bernstein Management Corporation proposes the Washington Housing Initiative, a nascent private-sector-led project by JBG Smith and the Federal City Council, as a new model for how to involve for-profit developers in affordable housing preservation.

Many of the responses also identified the challenge of relying on “race-blind solutions to a racist problem,” as Jonathan Nisly of MANNA, Inc. writes. But while the mechanisms of many of the proposed solutions are race-blind, the context in which they are implemented does not need to be: Nisly suggests using Racial Equity Impact Assessments as a tool to evaluate government actions and investments, much as a city might conduct Environmental Impact Assessments before beginning a project. Meanwhile, Aja Taylor of Bread for the City tackles the issue head-on, arguing that a suite of reparations policies is crucial to truly address the past centuries of economic violence.

Within the diversity of proposed solutions, all respondents identified how housing inequities are connected to other challenges, from employment to education to health. Many respondents stepped back to address the broader landscape of racial inequities in employment, income, and wealth that, in concert with ongoing racial discrimination, limit opportunity and economic mobility in the present day. To address these interlocking challenges, several cited the need to address the underlying income and wealth disparities that amplify housing disparities, using innovative approaches such as baby bonds and a guaranteed minimum income. However, fully addressing the roots of housing inequities may ultimately require a complete shift in mindsets: “Fundamentally, our country needs to recognize housing as a human right and fully support and fund a universal right to housing,” writes Monica Kamen of the DC Fair Budget Coalition. (Read more: Racial equity in Washington, D.C.)

Housing symposium essays

We invite you to read the full range of responses in this written symposium. You can jump to each entry individually by clicking on the individual links below, or scroll down to read the responses together in full:

- Reparations Now: Why Resource Distribution is the Key to Eliminating Racial Disparity – Aja Taylor (Bread for the City)

- Creating the Commons – Dominic Moulden (ONE DC) and Amanda Huron (University of the District of Columbia)

- A Case for Racial Equity Impact Assessments – Jonathan Nisly (MANNA, Inc.)

- Unlocking Housing Vouchers’ Potential to Reduce Racial Segregation – Claire Zippel (DC Fiscal Policy Institute)

- A Tax on Luxury Homes Would Help Preserve Equity in D.C. – Peter A. Tatian and Mychal Cohen (Urban Institute)

- A Closer Look at D.C. Rent Control in 2018 – G. Thomas Borger (Borger Management, Inc.)

- There Is No Silver Bullet – Monica Kamen (DC Fair Budget Coalition)

- Achieving Affordability in D.C. Requires Multiple Strategies – Chris Smith (WC Smith)

- The Imperative of Affordable Housing Creation for the Washington, D.C. Region – Joshua Bernstein (Bernstein Management Corporation)

- Investing Public Funds in Long-Term Housing Sustainability – Catherine Lampi and Fernando Lemos (Mi Casa, Inc.)

We would like to thank all the authors for their time and for their thoughtful responses. We would also like to thank the Consumer Health Foundation and the Meyer Foundation for their support and vision in creating this written symposium, and the larger series of publications on racial equity in the District of Columbia of which this is a part.

The views expressed in this series are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the D.C. Policy Center, the Consumer Health Foundation, or the Meyer Foundation.

Reparations Now: Why Resource Distribution is the Key to Eliminating Racial Disparity

By Aja Taylor, Bread for the City

I cannot remember a time I did not love D.C. This city, with its complicated realities and parallel truths, has always had deep roots in my heart. When I think about it, I think I inherited this love from my mother—a “crazy little woman from Kansas City” as she once put it—who had those same love-roots in her heart.

My mother came to love D.C. during a historically significant time, both for D.C. and national housing policy.

After more than three decades of anti-Black, anti-Jewish and anti-immigrant national housing policies, the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968. Prohibiting discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing, this landmark federal legislation deemed access to housing a civil right. This law—as well as other federal and local housing policies—would have an impact on my mother’s future, but barely 18 and at her first year of college at the Mecca in Chocolate City, the Fair Housing Act was not what was on her mind.

After graduation, my mom moved in and out of D.C. three times—once to St. Thomas, once to Chapel Hill and once to Kansas City. But D.C. kept calling her back. In 1984, she moved back to D.C. for the third and final time.

She and my father moved into an apartment on 17th and T streets NW. They didn’t plan to live in the small condo forever and hoped to eventually buy a home in their neighborhood. Their building was walking-distance from their jobs (my father’s job was directly across the street), public transportation, places to eat and buy groceries. They loved their neighborhood and their neighbors, and when she got pregnant with me the summer of 1985, that love was multiplied. The roots in her heart grew deeper.

That winter my mother learned that neither her love for the city nor the family she planned to raise in it were enough to keep her there. Their landlord went bankrupt and one day my parents got a notice their building, like many others in their nearly-Dupont Circle neighborhood, had been sold. Six young, white, college-aged people had pooled their capital together and bought the building.

My parents now needed to find a place to live. At the time, my mother earned $22,000 a year and my father had just started working for the Federal Government. They wanted to buy a home, but had no capital—certainly no family money, and they couldn’t qualify for a loan large enough to cover a home and repair costs for a fixer-upper. Now that their apartment was sold and a baby was on the way, they didn’t have time, either. And my own birth story as a little Black girl born at Washington Hospital Center 32 years ago was marked by the displacement of Black people on low incomes by more affluent white people with better access to capital. Three decades later, with babies being born to parents living in cars, shelters or housing that is unsafe, unhealthy, and unaffordable, displacement continues to have profound effects on Black children and other children of color.

My mother’s story as a Black woman in her 30s trying to build a life for her family in D.C. is one of many.

Forty-five years before my parents tried to make a life in D.C., another Black couple pursued the same dream. In 1944 James and Mary Hurd purchased 116 Bryant St. NW, becoming the first Black people to own and occupy a home in the Bloomingdale neighborhood. With that act, the Hurds defied the long-standing policy of racial covenants that prevented the sale of homes to “negroes,” to keep Bloomingdale white. Their white neighbors took issue. Some chose to move out of the neighborhood, a phenomenon known as “white flight.” But one couple, Frederic and Lena Hodge, filed a lawsuit with the District Court demanding that Hurd’s be denied a residence on that block. Their argument? Black people on the block reduced property values. The District Court sided with the Hodge’s, mandating that the Hurd’s and other recently-located Black families vacate their homes. As a part of a legal strategy to eliminate de jure segregation altogether, NAACP attorneys Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall were taking cases about racial covenants to the Supreme Court, and in 1948, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that courts cannot enforce racially restrictive covenants. This decision was a pivotal public policy moment, serving as part of the foundation for other desegregation decisions spearheaded by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, including Brown v. the Board of Education in 1954.

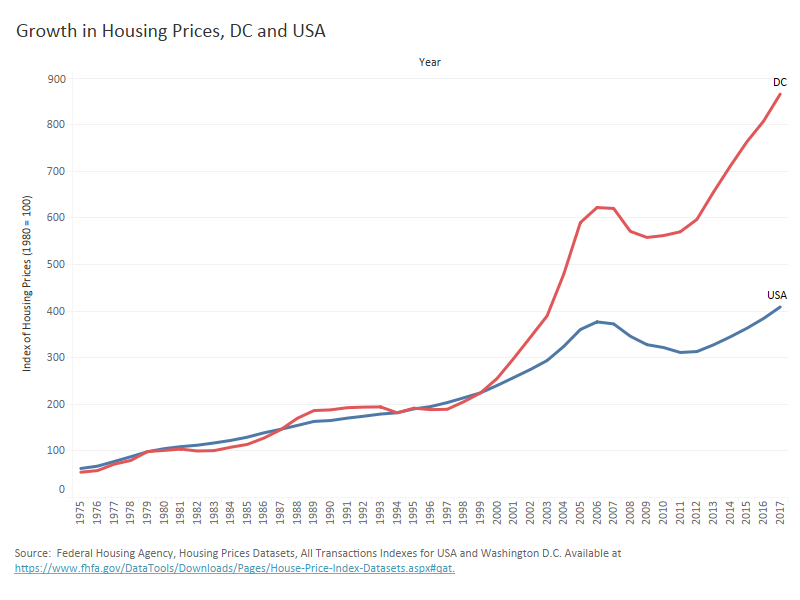

Yet declaring racial covenants illegal was not enough in itself to eliminate segregation. While de jure segregation was largely outlawed by the Brown v. Board decision, decades of racist housing and land policies ensured that de facto segregation persisted. Black and brown people did not have the economic and political resources to fully force desegregation, whereas white people were well equipped to continue with segregated lives. The establishment of the Federal Housing Administration enforced this divide with impacts still resonant today. The FHA not only made homeownership accessible to white people through guaranteeing loans, effectively creating the suburbs as subsidized housing for white people, but from 1934 to 1968, they also explicitly refused to back loans issued not just to Black people, but even anyone who lived near Black people. As a result of this and other practices, the wealth gap between white and Black residents has widened. The gap persists today and is greatest in D.C., with most of this gap related to homeownership—easily awarded to white families, but for many decades, denied to Black families.

To be sure, Black residents were not the only target of covenants. Anti-Jewish and anti-immigrant sentiments also employed covenants and FHA policies against Jewish people and other non-Christians. But while many Jews were later assimilated into whiteness (and its attendant privileges), communities of color continued—and continue—to experience the impact of anti-Black racism. Today Black people experience the lowest wealth accumulation rate compared to all groups in the country.

Government policies have intentionally excluded Black residents from homeownership and denied them a chance to build wealth.

Public policies like the G.I. Bill, the mortgage interest deduction and New Deal infrastructure projects created the white middle class, and helped them build and maintain wealth they could pass on to their children. Black families were intentionally locked out of these opportunities, instead only able to get public assistance for housing by living in slum-quality public housing units with little-to-no opportunity to ever purchase a home of their own. When Black families were able to finally live the “American Dream” and purchase homes in D.C., historical inequities once again crippled attempts to build wealth. Racism in the lending industry—as evidenced by higher cost mortgages offered to Black families, compared to white families with similar economic profiles—made the mortgage crisis of 2008 the biggest extraction of Black wealth in US history.

This historical framing is key, as poverty in Black and brown communities today have roots deeply entrenched in these explicitly racist policies, with consequences so catastrophic that social programs like housing vouchers and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) could never sufficiently remedy. Policies meant to dispossess Black people and other people of color were explicitly about resource distribution and wealth accumulation, and the aforementioned programs—all appallingly underfunded—barely keep people afloat. Even when looking at homeownership programs like the Housing Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP), often touted as a mechanism for providing wealth-building opportunities to Black residents and other marginalized racial groups, is not only not targeted specifically toward Black people and other people of color, but also lacks data backing up its claims that it is creating wealth-building opportunities for Black people and other people of color in ways that are statistically significant, or widespread. Rising housing costs also means that the amount of assistance available (offering at most $80,000 for a family of four at 50 percent of AMI) is not sufficient to make homeownership a reality for enough Black people in the city, whose median income is $41,000. The need for drastic government intervention to redistribute resources is clear. But what would that look like?

The most critical public policy intervention to increase affordable housing and begin to rectify centuries of economic violence against Black people and other people of color is a suite of reparations policies.

The government created a society where race and zip codes can reliably predict outcomes. Therefore, the government—including the District’s own local government—must compensate for what it created, and make reparation to the residents who have been continuously locked out of the city’s economic prosperity.

The two most critical interventions to begin to rectify decades of historic and current law that disadvantages Black residents and other people of color are capital redistribution and providing access to safe, healthy housing that people can afford even on a low income—including both rental and collective ownership opportunities.

Capital distribution can happen in a combination of ways, including baby bonds and a Guaranteed Minimum Income system. This capital distribution program should run at minimum for 34 years (the length of time the FHA intentionally discriminated against Black people), and should be paid for not solely by the government but also by nonprofit institutions, banking institutions, the developer class, universities, philanthropy and any other institutions that continue to benefit from the oppression of Black residents and other people of color.

The city must also invest in state-of-the-art public housing and the financing of limited equity co-ops. For example, the city should build state of the art public housing—like this Singapore model—where rent goes according to your income. The city could achieve its goals of economic integration without destroying communities by ensuring that people at multiple income levels could live in this housing. There are already current private market developments that operate similarly (for instance developments that have set-asides for people at 0-30 percent of AMI, 50 percent of AMI and 60 percent of AMI), but the difference is that this would be a public option where instead of set rents for each income level, the rent fluctuated based on your income.

State-of-the-art public housing would provide housing that is permanently affordable, attractive, and healthy for people on low incomes, and city ownership means greater oversight and authority over its operation. Imagine children able to focus on school and just being kids instead of focusing on whether they have a safe place to sleep. Public housing has long been the one truly affordable housing option for people living on low incomes, and rental opportunities will always be a crucial part of D.C.’s housing stock. Not everyone is interested in ownership, or even co-ownership, but for those who are interested, the city must invest to make sure that it is a possibility for more people on low incomes.

There are many obstacles to a locally enacted reparations program in D.C., but it is imperative we try.

The most daunting obstacle is how to enactment of a local program without similar federal acknowledgement, or even without losing federal funding in the process. The practicality of implementation is also a challenge, especially as you consider D.C.’s unique economic stratification and the fact that affluent neighborhoods like The Gold Coast have concentrated Black wealth—though even many of these families of wealth have moved out of the city. While it’s true that nearly 100 percent of D.C. residents in poverty are people of color, it is also true that some Black folks have been able to accumulate enough wealth for there to be at least a couple generations of well-off people in their family. Even these families deserve reparations, as they were still impacted by racist policies. Additionally, being Black all my life means knowing that achieving that level of wealth has come at a tangible cost. The mental and emotional toll of having to be twice as good, enduring overt racism from colleagues and businesses, so-called microaggressions, still being Black when the cops pull you over in your own neighborhood and so much more.

There is also the question of how we fund such a robust, expensive policy. The Council’s Budget Office found that a Universal Basic Income that to brought every households’ income to D.C.’s cost of living would cost the city around $20 billion over ten years. Add to that the estimated $2.6 billion the city would need over ten years to fund the creation of 30,000 units of deeply affordable housing and the price tag just grows. Nonetheless, for a city that can figure out how to subsidize billionaires and a city that claims to want to be racially just, the question of reparations cannot be whether we do it, but rather, how.

In “Where Do We Go From Here?,” an address delivered at the 11th Annual SCLC Convention, Dr. Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Power without love is reckless and abusive, and love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best is love implementing the demands of justice, and justice at its best is power correcting everything that stands against love.” He spoke in 1967, but his words remain particularly relevant today. The love of too many people in positions of power feels at best sentimental and anemic, like crying on the dais while voting against dignified conditions for homeless children. At worst it feels reckless and abusive when we live in a city willing to subsidize people so rich they don’t know how they’ll spend their money while looking homeless families in the eye and saying we have no money to house them.

It’s time the city began to seriously figure out what form reparations will take, and when. And if it is not in the interest of the current political establishment, then it is up to the people of this city, especially those who claim to want to live in a more racially equitable D.C., to either make them change their minds or make them change their seats.

Creating the Commons

By Dominic Moulden, ONE DC, and Amanda Huron, University of the District of Columbia

A slowly growing population in the radical left community realizes that it is high time for human beings to create a human economy. We need an economic system that meets basic needs and works for the benefit of human life, not an individualistic capitalist lifestyle. A critical component of an economy based in real human needs is community control of land. The way we envision community control of land is through the commons.

The commons can be understood as a set of resources that have been de-commodified: that is, these are resources that are used to directly support life, rather than to extract a profit through sale on the market. In addition, the commons are collectively governed, and sometimes owned, by the people who use them. The community of people who use the resource, and help to govern it, are known as commoners.

Who is this community? The community is made up of those people living in the affected area, and those people trained, coached, and educated in commoning: that is, in how to work together to democratically control and manage community resources, including not just land, but also housing, schools, food, environment, wellness, and other aspects of human life. All resources are held in a common with principles, rules, and accountability to a committee of leaders cultivated and nurtured in practices of commons lifestyle. These leaders are recognized because they made a commitment to a new lifestyle—one not centered on the exploits of capital, but on the social ecosystem of collective work and communal living. The marketplace is not land and capital, but a space and place for building bonds with people and community.

One example of the commons can be found in the limited-equity housing cooperatives of Washington, D.C. These are co-ops that have been purchased by their low-income members, with financial assistance from the city, and removed from the speculative market. They provide long-term affordable housing for their members and are democratically controlled by their member-owners. These co-ops are a testament to the strength and organizing power of their members. Yet some of them struggle with the challenge of maintaining a commons in the midst of a hyper-gentrifying city. In order to ensure long-term, sustainable community control of land, we need to build structures that support the work of smaller-scale enterprises like these individual co-ops.

One way to build this structure is through a community land trust. A community land trust is governed both by the people who live in homes on the land trust, and also by people who live in the surrounding area and are dedicated to the long-term sustainability of the commons. This dual governing structure ensures that the needs of individual land trust households and the larger community are met.

Examples of the land trust vision can be found in Boston’s Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative and Vermont’s Champlain Housing Trust. The sole purpose of land trusts is to meet the needs of the community and environment. The shareholders’ vulture culture is removed. Nonetheless, we need to be prepared to reorient all community members to unlearn the capitalist and economic death habits of exploitation of people and the earth to the maximum extent possible. The economic life of a commons is focused on birthing and nurturing to build life through meeting the basic needs of human beings rather than a marketplace controlled by ruthless profiteers and greed.

This essay was originally published on Shelterforce.

Back to list of essays

A Case for Racial Equity Impact Assessments

By Jonathan Nisly, Director of Housing Advocacy and Outreach, MANNA DC

At MANNA’s Homeownership Town Hall in April, At-Large Councilmember Robert White argued that, because the federal government and local governments across the country are largely responsible for the racial wealth gap in the United States, they must take leadership in closing it. “As much as government has been part of the problem,” declared Councilmember White, “it must now be part of the solution.”

There can be no question that government has been part of the problem. Even the history of racist policies just within the District since the start of the 20th century deserves volumes. Alley clearance in early 20th-century Georgetown displaced thousands of Black families, many of them homeowners who were never fully compensated. Urban renewal and “slum clearance” in the Southwest quadrant did the same. When these thousands of families could not find places to live, both because of the District’s heavy use of racial covenants in deeds and because the vast majority of their wealth had just been stolen out from under them, the government segregated them into public housing projects largely concentrated across the Anacostia River. That has contributed to a reality in which the average white family in D.C. has 81 times the wealth of the average Black family.

However, thanks to the advocacy of long-time residents, as well as the political will of politicians like Councilmember White and others since the start of Home Rule, the District government has indeed taken steps to be part of the solution. Former Mayor Marion Barry, perhaps because of his well-documented faults, has not received proper credit for the variety of programs instituted under his administration that have worked effectively to achieve this reality. The Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP) now allows up to $80,000 in down payment assistance for lower- and middle-income District homebuyers, with the vast majority of borrowers being people of color. Mayor Bowser’s commitment to $100 million each year for the Housing Production Trust Fund has been historic and significant in slowing displacement in communities of color, although more funding is now needed. The Local Rent Supplement Program, a rental voucher program like HUD’s Housing Choice Vouchers, has similar impact and opportunity for expansion. There are numerous other programs that try to address this issue as well, although, like the above programs, all are a race-blind solution to a racist problem.

Unfortunately, the government never fully stopped being part of the problem. For every program like HPAP with its yearly budget of (soon to be) $24 million, there are examples of mammoth wealth transfers in the opposite direction. The Wharf, for instance—the District’s new megadevelopment that finally filled the hole left by the last century’s urban renewal efforts in Southwest—received close to $300 million in public subsidy. With affordability requirements that only moderately surpass the inclusionary zoning laws already in place, that money is likely to serve primarily as a subsidy to a wealthier, whiter community than the one displaced 60 years ago.

This sort of alternative welfare for the rich happens all the time. Currently, the Council is debating $50 million in public money to facilitate the conversion of downtown office buildings into primarily luxury housing. That debate harkens back to the 1990s, when the Office of Planning changed an incentive structure away from producing neighborhood-based affordable housing. Attaching luxury housing to downtown buildings was instead deemed the desired public good, and the weight of government intervention led to downtown homes created for a majority white, overwhelmingly wealthy set of Washingtonians. Yet this kind of subsidy for the wealthy is absent from most conversations about government assistance. There is a growing sense at the Council that the District has done all it can to subsidize lower-income long-time residents, even as the subsidies for wealthier, predominantly white newcomers continue to grow decade after decade.

Racial equity impact assessments (REIAs) can serve as an essential corrective to these one-sided conversations. Similar in nature to environmental impact studies, REIAs can help decisionmakers more fully understand the effects of their choices. REIAs have the opportunity to be incredibly complex in their forecasting and calculations, but they can also be wonderfully simple and accessible. A template adapted from the Portland Public Schools system covers just the following questions:

- Who are the racial/ethnic groups affected by this contract, policy, program, practice, or decision?

- Does this contract, policy, program, practice, or decision ignore or worsen existing disparities or produce other unintended consequences?

- How have you intentionally involved stakeholders who are also members of the communities affected by this contract, policy, program, practice, or decision?

- What are the barriers to more equitable outcomes?

- How will you mitigate the negative impacts and address the barriers identified above? What resources are needed to address these barriers?

- Which racial/ethnic groups will carry the greatest burden if the proposed policy is implemented? Which racial/ethnic groups will gain the most benefit?

Questions like these have the potential to transform conversations around multi-million-dollar public subsidy for luxury housing. Rather than decision making being carried by a vague notion of continued growth and development, an REIA could focus the conversation to a few simple points: Black Washingtonians currently have only 1 percent the wealth of white Washingtonians, and another public investment in high-end housing is likely to widen that gap. Conversely, conversations around programs like HPAP could be equally enlightened: The down payment assistance program used primarily by people of color helps extend homeownership and shrink the District’s racial wealth gap.

As the questions indicate, however, the potential for REIAs extends far beyond public contracts and programs. REIAs are already used by several states in considering appropriate criminal sentencing. The oft-cited racial sentencing disparity in crack and powder cocaine, with drastically harsher sentences for crack cocaine’s majority-Black users than powder cocaine’s majority-white users, has led to public consciousness around sentencing disparities. Other jurisdictions across the country, including Takoma Park, Maryland as of 2017, have begun using REIAs as a general legislative check.

The following are a few brief examples from the many times in the past year that the District could have benefitted from an REIA process:

- Estate tax cut: In 2017, the District decided to spend $16 million per year in foregone revenue to raise the floor for the estate tax from $2 million to $5.49 million. A simple REIA could have investigated the racial breakdown of beneficiaries from this increase—given the District’s racial wealth gap, it is likely the vast majority of beneficiaries are white—and noted that a raised floor for the estate tax perpetuates the generational transfer of wealth along racial lines. This prolongs and increases the racial wealth gap, while simultaneously leaving less revenue available for programs that could shrink that gap.

- New District-vehicle parking in Ward 5: Langdon Park, a majority-Black neighborhood in Ward 5, discovered in July 2017 that it was the new pick for parking the District’s fleet of ambulances, emergency vehicles, and trucks. With Ward 5 already suffering from an over-abundance of industrial sites, and with the District, like most major cities, possessing an asthma epidemic that largely falls along racial lines, this was a decision that could have benefited greatly from an REIA process. Additionally, District officials specifically cited that the old District parking site in the fast-gentrifying Shaw neighborhood had become too “commercially desirable” for such a purpose. An REIA could have pointed out that that commercial desirability was due to an influx of wealthier, whiter residents, and that moving this source of pollution back to a majority-Black neighborhood would in fact increase the District’s long-standing problems with environmental racism. The District also failed to follow legal requirements for notifying Langdon Park’s Advisory Neighborhood Commission, another oversight that could have been corrected by the above REIA template. As pressure increases to move other “commercially desirable” industrial areas, this problem is likely to continue.

- Expansion of nuisance laws: In response to residents’ legitimate concerns about businesses that were aiding in drug sales, the Council is currently considering a bill that would expand a nuisance abatement law. This bill would give landlords and the District more leeway in pursuing legal action against tenants accused of illicit drug, firearm, and prostitution activity. If the Council had conducted an REIA, however, they would have found significant research on the discriminatory impact of nuisance laws, as well as stories from residents whose communities are affected by these statutes. Luckily, local activist groups turned out residents at the bill’s hearing to educate the Council on those effects, as well as the danger of advancing laws dependent on suspicion and unproven allegations. A brief review of recent news shows high profile calls to the police for cases of Black people playing golf too slowly, barbequing legally in public spaces, using Airbnb, sitting in Starbucks, and sleeping in their own college dorms. Clearly, scrutiny as to what constitutes a “nuisance” is often tinged with racial bias.

In each of the above instances, local advocacy groups and residents mobilized to alert District officials as to the unequal impact of their decision-making, with varying degrees of success. Those efforts could likely have been significantly more fruitful if there had existed from the beginning a document written by the District itself identifying and corroborating residents’ points of concern.

Unfortunately, a central problem that emerges in contemplating the creation of an REIA process in the District is determining its breadth. Although maximum impact would be achieved by covering contracts, legislation, policy, practice, criminal sentencing, and more, each additional area of focus would complicate any such bill’s success in moving through the Council and then being fully implemented. Advocates and supportive Councilmembers would likely be well served to select two or three items from the above list for initial legislation, with the goal that a successful implementation will lead to an expansion of REIA usage.

Ultimately, however, questions as to the breadth of such a bill may pale in comparison to a much larger issue—who, or what agency, will be charged with crafting these REIAs? Any such entity must have significant political independence and community accountability. Without these features, the REIA process would be in danger of becoming a political rubber stamp, simply another box to check in pursuing the same policies and outcomes. Advocates and other residents will need to work collaboratively with the Council in identifying the appropriate governance structure and public input processes.

As public awareness continues to increase as to government’s historical role in the creation of the District’s and the country’s racial wealth gaps, advocates must seize the moment to educate the public about the ways in which governmental subsidies and legislation continue to unintentionally exacerbate that gap today. Racial equity impact assessments present the opportunity to not only start closing the racial wealth gap and advancing racial equity in new ways, but also to change the conversation about who in the District depends on government subsidy. Until there is a general acknowledgment of the millions of dollars in subsidy received each year by wealthier, predominantly white District residents, there is little hope for change. But with a robust REIA process in place, this subsidy—and topics as diverse as disparate environmental impact and discriminatory policing practices—can all be elevated in the governmental decision-making process. With that, hopefully, government can start to holistically be part of the solution.

Back to list of essays

Unlocking Housing Vouchers’ Potential to Reduce Racial Segregation

By Claire Zippel, DCFPI

The District’s newfound prosperity has not benefitted all residents—or all neighborhoods—equally. Citywide, racial inequities persist across nearly every metric of economic and physical well-being, and economic segregation has actually deepened in recent years. In neighborhoods that have seen an influx of investment and resources, rising housing costs risk pricing out existing low-income residents who could most stand to benefit from the new opportunities. However, one existing housing program has particularly striking—but unrealized— potential to reduce segregation and give low-income residents a foothold in gentrifying neighborhoods: housing vouchers. Federally- and locally-funded housing vouchers, in theory, enable residents to afford an apartment of their choice, regardless of location; in practice, voucher holders face high barriers in competitive rental markets. By adopting policies that forge landlord partnerships and boosting households’ ability to make “opportunity moves” to more highly resourced neighborhoods, the District could unlock housing vouchers’ potential to reduce racial inequities and improve the lives of thousands of residents.

D.C.’s Changing Neighborhoods

Gentrification of many historically Black D.C. neighborhoods (particularly those Wards 1, 2, and 6) has brought increased investment to previously under-resourced areas. It has also brought rising housing prices that can threaten longtime residents’ ability to remain and benefit from the new opportunities generated by their neighborhood’s economic growth. As more D.C. neighborhoods experience lower poverty and crime rates, have higher-performing schools, and see increased access to transit and amenities, the city is faced with an urgent question: Will longtime, Black D.C. residents be able to remain and benefit from these changes?

Meanwhile, the neighborhoods east of the Anacostia River—populated largely by low-income and Black residents—remain under-resourced. These areas, which have been shaped by a legacy of public and private disinvestment, also have what remains of D.C.’s ‘naturally affordable’ housing. Nearly half of the District’s Black population is located east of the Anacostia River, meaning that Black residents are concentrated in the part of the city facing the most severe economic challenges.

Spatial inequality and its intersection with race are not new—and indeed, not accidental, as demonstrated by the District’s and the nation’s history of racially discriminatory housing and urban development policies. Yet it has troubling implications for the city’s future. When low-income and Black residents are concentrated in more economically challenged areas, and are increasingly unable to afford to live in more prosperous ones, opportunities to benefit from growing prosperity can be foreclosed: One’s future economic mobility is highly contingent on one’s neighborhood. Recent evidence has shown that young children in families who moved to a low-poverty neighborhood from a high-poverty one earned more as adults and were more likely to attend college. For adults, the move improved mental and physical health, as well as perceived neighborhood safety.

These findings suggest that the potential displacement of low-income residents from gentrifying areas due to rising housing costs, as well exclusion from high-income enclaves, may exacerbate the inequities experienced by not only current, but future generations of low-income Black D.C. residents.

Housing Vouchers Have Unrealized Potential to Reduce Segregation

Many public policies and private practices hold the potential to give longtime and low-income District residents a foothold in areas with high or rising housing costs and unlock access to longstanding “high-opportunity” neighborhoods. The District should pursue policies such as proactive affordable housing preservation and creation in gentrifying communities, wealth-building through homeownership, strengthening tenant protections, and working with communities to develop an “equitable development” plan (the 11th Street Bridge Park’s is an excellent example) for each city-involved economic development project.

Yet one existing program has particularly striking—but unrealized—potential, and may require only relatively small enhancements to fulfill its promise. Federally- and locally-funded housing vouchers assist nearly 15,000 low-income District households,[1] 98 percent of whom are headed by a person of color.[2] Eighty-five percent of these households are extremely low-income—the group most likely to face severe housing cost burden, and the least able to cope with rising housing prices.

In principle, housing vouchers eliminate the affordability barrier to accessing high-opportunity neighborhoods, and insulate households from rising housing prices in gentrifying areas. Housing vouchers allow households to rent a private-market unit of their choice (within certain cost limitations); the household pays an affordable share of its income for rent, and the voucher covers the rest. Vouchers thus hold the unique potential to unlock high-opportunity neighborhoods precisely to those who have historically been excluded from such areas. Moreover, vouchers can enable households to remain in, or move back to, a neighborhood transformed by gentrification—thus curtailing or even reversing the threat of displacement due to rising housing costs.

It is worth noting that the principle behind housing vouchers is that a family is empowered to choose whichever neighborhood is right for their family. For some, that may mean moving to a community with lower poverty rates. For others, living close to family and kinship networks is an important source of social and material stability, which may offset the benefits of leaving one’s neighborhood in search of another, even one with higher-performing schools or better amenities.

In the District, the promise of housing vouchers to help families seek less segregated neighborhoods is largely unrealized. District households assisted through the federally-funded Housing Choice Voucher Program (HCVP) are no more likely than residents of site-based federally subsidized housing (such as public housing or Section 8) to live in a low-poverty neighborhood (defined here as a census tract with a poverty rate below 10 percent).[3] The poverty rate of HCVP households’ census tracts of residence is 28 percent on average (the citywide average among tracts is 19 percent[4])—no better than that for households in site-based federally subsidized housing.

Not only—and not coincidentally—does the location of HCVP households follow patterns of economic segregation, it follows racial segregation as well. HCVP households—98 percent of whom are headed by a person of color—are no less likely to live in a racially segregated neighborhood than other federally-subsidized households. On average, HCVP households live in a neighborhood where 90 percent of the population is a person of color (the citywide average among census tracts is 66 percent[5])—again, no better than for site-based programs.

The uneven distribution of rental housing throughout the city may be one factor, but it explains relatively little of the disparity. About 58 percent of the District’s HCVP households live in Wards 7 and 8,[6] a disproportionate share as that those Wards contain only 26 percent of the city’s renter-occupied housing.[7] The District’s locally-funded voucher program, the Local Rent Supplement Program (LRSP), follows a very similar pattern, with 64 percent of LRSP households living in Wards 7 and 8.[8]

These disparities are especially striking given that the District has adopted one of the most prominent best practices recommended by national experts to expand voucher holders’ access to high-opportunity neighborhoods: small area fair market rents. The D.C. Housing Authority sets the maximum monthly voucher payment (which sets a ceiling for the rent of a unit a voucher holder can choose) for 57 neighborhoods in the city based on rental market analyses. Voucher holders can thus choose a higher-priced unit if it is located in a higher-priced rental market. A neighborhood’s high rental prices, therefore, should not in theory be a barrier to voucher holders locating there.

However, as outlined above, few voucher holders live in low-poverty neighborhoods, and only about 15 percent live in D.C.’s costliest Wards (2, 3, and 6). In early 2017, DCHA raised its HCVP fair market rents in select high-opportunity neighborhoods (largely Wards 2, 3, and 6) up to $3,000 for a two-bedroom apartment. It is too soon to tell if this policy change has increased the likelihood that voucher holders will locate in such neighborhoods.

Breaking Down Marketplace Barriers

Yet while family and community ties may account for some of the concentration of HCVP households, there are several known barriers that play a large role in whether households with vouchers can successfully locate and lease an apartment in the neighborhood of their choice. Therefore, policymakers must address the multiple ways that voucher holders may be locked out of high-opportunity neighborhoods.

First, the District’s existing fair housing laws must be more strongly enforced. For instance, despite the fact that it is illegal in the District for landlords to refuse to accept housing vouchers (“source-of-income” discrimination), this type of discrimination is not uncommon. Additionally, households with vouchers—who are more likely to be people of color and have children than other renters—may face illegal housing discrimination or steering on the basis of race and family status. Some landlords may also deny a voucher holder’s application due to a past arrest or conviction record, even though landlords’ ability to consider arrest and conviction records was recently restricted by the Fair Criminal Record Screening for Housing Act of 2016. As with source-of-income discrimination, this law must be enforced in order to be effective, and landlords must be educated on how to comply.

In addition, policymakers should address some of the other (legal) reasons why households with vouchers may be turned away from apartments. We know that voucher holders may be turned away due to low or no credit scores, or for past evictions and rent arrears; while these are legal reasons for refusing an application, inflexible credit and rental history requirements can enable de facto, if not de jure, discrimination against voucher holders. Furthermore, because a poor rental history or low credit score may simply represent a family’s prior lack of affordable housing, it is unclear whether stringent credit and rental history screening criteria is as necessary when families have a voucher. It is also important to note that credit scores have been shown to perpetuate racial disparities. The District should explore legislation that restricts landlords’ ability to consider voucher holders’ credit scores, though landlords would likely oppose it.

Forging Landlord Partnerships and Boosting Opportunity Moves

There are further steps the District should consider to help ensure that all families with vouchers are able to rent a home in the neighborhood of their choice, including actively encouraging landlords to rent to households with vouchers. Several jurisdictions have established “risk mitigation” funds that incentivize landlords to apply more inclusive screening criteria to households with vouchers. Such funds—typically targeted to formerly homeless residents—agree to cover damages or unpaid rent up to a certain amount. Participating landlords rarely need to make claims against risk mitigation funds, indicating that such funds mitigate perceived, rather than actual, risk. Similarly, the recently-launched D.C. Landlord Partnership Fund encourages landlords to rent to formerly homeless residents in D.C.’s Rapid Rehousing and Permanent Supportive Housing programs. The Fund, an initiative of the Department of Human Services, Downtown BID, and the Coalition for Nonprofit Housing and Economic Development, represents a promising public-private partnership. If positive outcomes are demonstrated under the current scope, expanding the fund to all federally- and locally-funded voucher programs could be effective as well.

In addition, policymakers and private funders should also look closely at services aimed at increasing voucher households’ success in the rental market and empowering them to seek housing in high-opportunity neighborhoods. Several jurisdictions have adopted programs designed to increase “opportunity moves” by providing counseling services and material assistance to families with vouchers. Mobility programs typically include security deposit assistance, credit and financial counselling, and mobility-focused housing search assistance. The latter aims to reduce the knowledge gap that can exist among low-income families about higher-opportunity neighborhoods. The D.C. Housing Authority (DCHA) began a light-touch mobility program in 2016. The program, called Housing Affordable Living Options (HALO), includes mobility counseling, education on landlords’ application criteria, and workshops on how to succeed as a tenant. HALO also includes targeted outreach to landlords in low-poverty neighborhoods. The program is small, and like many mobility programs, it is voluntary, so it attracts those who are likely already considering and interested in moving to a high-opportunity area. That said, HALO’s outcomes seem promising so far: 90 participating families have moved to low-poverty areas, and 108 additional families are searching for housing in low-poverty areas, according to DCHA. The District government or philanthropy community should pitch in to expand the HALO program (and include an evaluation component to inform its progress).

Notes

[1] U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2017 Picture of Subsidized Housing dataset; D.C. Housing Authority performance oversight documents submitted to the D.C. Council Committee on Housing and Neighborhood Revitalization, Feb. 2018.

[2] This and the next figure are for HCVP households only; demographic data on LRSP households is not available.

[3] Author’s calculations using U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2017 Picture of Subsidized Housing dataset and U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates, Table S1701, for census tracts in the District of Columbia.

[4] U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates, Table DP03, for census tracts in the District of Columbia.

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates, Table DP05, for census tracts in the District of Columbia.

[6] D.C. Housing Authority performance oversight documents submitted to the D.C. Council Committee on Housing and Neighborhood Revitalization, Feb. 2018.

[7] U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey 5-year estimates, Table DP04, for Wards (state legislative districts) in the District of Columbia.

That family-sized rental housing may be even more concentrated in low-income neighborhoods than rental housing in general, is a possible factor as well. HCVP households are more likely to have children than D.C. renters overall.

[8] D.C. Housing Authority performance oversight documents submitted to the D.C. Council Committee on Housing and Neighborhood Revitalization, Feb. 2018.

Back to list of essays

A tax on luxury homes would help preserve equity in D.C.

By Peter A. Tatian and Mychal Cohen, Urban Institute

According to Census Bureau estimates, Washington, D.C. has grown by 20 percent between 2000 to 2016, adding another 109,000 persons to the city’s population. And more new residents arrive every day. Forecasts see the city’s population reaching almost one million in the years ahead. If Amazon’s HQ2 development comes to our region, those projections could well become a reality.

All these new people need places to live, which has increased the demand for housing in D.C., leading to a building boom throughout the city. Despite all the construction, housing demand has outpaced supply, driving up costs. Neighborhoods previously affordable for lower-income Washingtonians are now becoming out of reach.

As the trend continues and spreads, people without means—frequently people of color who have lived here for generations—are being excluded and displaced. In 2017, Urban Institute updated its estimates of possible demographic changes by the year 2030. The Black population of Washington, D.C. is estimated to fall to 33 percent of the overall population, down from 51 percent in 2010 and 61 in 2000,[9] based on average rates of births, deaths, and migration. This would mean a drastic change in the racial makeup of the city, even without taking into account local policies or developments that could accelerate changes. In a recent survey of households in the DMV (D.C.-Maryland-Virginia) metropolitan area, about 40 percent of people of color indicated that they knew someone in the past two years who had to involuntarily move from their jurisdiction in the past two years .

If long-term residents of color are at greater risk of displacement than ever, what are the possible solutions?

While increasing housing production is part of the answer, building alone will not suffice to solve this problem. Chief Economist Ted Egan, in an analysis of San Francisco’s housing market, estimated that an increase in the city’s housing production by 3,160 units per year, well above current levels, would reduce housing prices by only 1 percent—equivalent to $10,000 in sales price or $35 per month in rent. It is likely that D.C. would face similar challenges in turning the cost curve solely through production increases. Furthermore, the D.C. housing market has demonstrated that, unaided, it cannot (or will not) produce new housing for lower-income residents.

D.C. already devotes considerable resources to affordable housing, but it is clearly not enough. Where can more resources come from? An idea that has been tried or is being considered in other places could be an option here – a tax on “luxury” homes. Capturing the value of high-end development to finance affordable housing is not a new concept. The Battery Park City development generated hundreds of millions of dollars that went toward renovating housing in New York City’s poorest neighborhoods. A new tax on high-priced homes in British Columbia is estimated to generate $200 million.

A Redfin search found over 430 homes in D.C. currently listed for sale at $1 million or higher; in 2015, 653 homes sold for $1 million or more. Data from the Office of Tax and Revenue indicates that 14,861 homes and condos valued at $1 million or higher. These expensive homes are frequently located in neighborhoods with few or diminishing affordable housing options—including areas where existing assisted housing is under threat. In other words, places that have long been, or are quickly becoming, exclusionary.

An additional tax on the sales or values of $1 million homes could generate additional revenue for housing assistance that could help Washingtonians remain in their city. A 0.1 percent luxury tax on homes valued at $1 million or more would have generated $25.4 million in property tax revenue in 2017. A 1 percent luxury transfer tax on home sales of $1 million or more in 2015 would have generated $9.8 million in revenue. The rate of taxation could scale up or down depending on what is feasible and necessary to close the housing gap. And given that D.C.’s residential property taxes are relatively low compared to many states, it would seem the District could easily handle this tax increase.

What would we do with the money? Production subsidies (like the D.C. Housing Production Trust Fund) are important, and should continue to be fully funded, but it may not be possible for developers to absorb much more revenue quickly. Since the affordability needs are immediate, we recommend that most of the money from a new luxury homes tax go into expanding the D.C. Rent Supplement Program. This program augments the supply of federal Housing Choice Vouchers, which is unlikely to be significantly expanded by Congress in the foreseeable future. Urban Institute estimated that, in 2009-11, there were only enough vouchers and public housing units (which serve similar low-income populations) for two out of every five eligible D.C. households. D.C. created the Rent Supplement Program to help address this shortfall.

The political will to impose a luxury home tax is the main obstacle to implementing this idea. New taxes are rarely popular, both due to resistance from those who are being asked to pay and because of concerns of hampering economic growth. As economist Adam Ozimek argues, however, taxing housing wealth is “efficient compared with taxing other kinds of wealth because it’s impossible to move and difficult to hide.” In addition, very few ultra-expensive homes are new construction, so a luxury home tax will not dampen production. D.C. already has a refundable tax credit that lowers property tax burdens on homeowners who are low income. D.C. also reduces the effective property tax base and limits annual tax increases for principal residences through its homestead exemption. A luxury home tax would extend the progressivity of D.C.’s property tax system and provide much needed funding for affordable housing assistance.

Note

[9] Data Updated 2017.

The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders.

Back to list of essays

A Closer Look at D.C. Rent Control in 2018

by G. Thomas Borger, Chairman, Borger Management, Inc.

Since 1973, Washington, D.C. has had some level of price controls on rental housing. Initially, rent control was enacted in D.C. as part of President Nixon’s national wage and price control program. The initial program was intended to be a temporary measure, but when the Rental Housing Act of 1980 was passed by the City Council, rent control became a permanent fixture in the D.C. housing market and local politics. The primary goal at that time was to prevent displacement of lower-income residents through arbitrary rent increases and evictions. At the time the Act became effective, the city faced significantly declining population trends, as well as a reduction during the 1970s in the rental housing stock of approximately 30,000 units. City-wide rents averaged about $250 per month ($661 in today’s values). In addition to the large number of substandard dwelling units further aggravated by lax enforcement of housing codes, there were thousands of vacant housing units across D.C. New apartment construction was minimal.

Today the housing market has changed dramatically in terms of cost, affordability, new construction, and gentrification of neighborhoods. Although the rent control regulations have undergone major changes and modifications during the past 38 years, rental housing is still heavily impacted by this legislation.

The results of decades of rent control are uneven, and proponents of rent control, housing providers and elected officials often have contradictory views of its impact on the supply and preservation of affordable housing. Since affordable housing is unarguably a major factor affecting racial segregation, gentrification, and livable neighborhoods in Washington, D.C. and other major cities, I have attempted to help frame the dialogue on these issues by focusing upon the impact of rent control and how it has shaped the current rental market. I have based my comments on over 40 years of experience as a rental property manager and owner in Washington, D.C.

The Legacy and Future of Rent Control in D.C.

Rent control has produced uneven results and unintended consequences for an aging housing stock, but it has had some unquestionable successes: A vulnerable segment of the population has been protected from displacement and older properties have been recycled into modern rental apartments. The effects are hard to track— although approximately 70,000 rental apartment units are under rent control, the percentage that are affected by the price control aspects of the regulations is not known or measured. And except in the context of rent control legislation dealing with regulation of rent increases, legislatively very few, if any, fresh and innovative ideas to address housing affordability have been debated in the public forum of the D.C. City Council.

Legacy rent-controlled apartments are an asset to the city because long-term owners typically have lower debt ratios and tax considerations that mitigate the urgency to sell or propensity to neglect the properties. Historically low mortgage interest rates and the availability of credit for rent-controlled properties during the past eight years has enabled many property owners to refinance their buildings, improve their cash flow and set aside funds for capital expenditures. As interest rates rise, however, this favorable situation will deteriorate. Meanwhile, real estate taxes, water and sewer rates, utility cost and labor cost increases for apartment owners has significantly surpassed increases in inflation as measured by in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Furthermore, property improvements that meet current Green Building Requirements—which should be a goal of all urban centers, and address utility consumptions, environmental conservation and resident responsibility—are difficult to achieve under the rent control regulatory process.

Despite rent control, there is a diminishing supply of rental apartments in certain neighborhoods that are affordable to middle- and moderate-income families. New market rate apartment buildings are not affordable to low- and moderate-income residents without either Inclusionary Zoning or Housing Choice Voucher Program subsidy. At the same time, legacy rent-controlled properties face increasing operating cost and capital improvement expenditures (both because of their age, and because of regulations) that require corresponding increases in rental income.

The optimum housing environment is one in which families of varying income levels share the same neighborhoods and services. However, affordable rental units are disproportionately located in Ward 5, 7 and 8, and in these areas, where market forces tend to keep rents affordable. In other Wards, however, apartments are significantly below the market rent for any particular building and/or neighborhood. When vacated, the new tenant is not mean-tested and the owner is not obligated to re-lease to a resident in need of an affordable apartment. (Across the city, senior citizens of moderate income do not pay the annual 2 percent base rent increase, and since CPI increases have been negligible, their rents have remained flat for the past five years.)

Looking ahead, it will be important for policymakers to consider the increasing concentration of affordable units in a limited area of the city, and how policymakers can use the affordable housing tools at their disposal to create a more equitable city for all.

Disclaimer: G. Thomas Borger is a funder of the D.C. Policy Center.

Back to list of essays

There’s No Silver Bullet

By Monica Kamen, Co-Director, DC Fair Budget Coalition

“The poor in America know that they live in the richest nation in the world, and that even though they are perishing on a lonely island of poverty they are surrounded by a vast ocean of material prosperity. Glistening towers of glass and steel easily seen from their slum dwellings spring up almost overnight.” – Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964

In our nation’s capital, luxury condominiums with pet spas, waterfalls, and yoga studios overlook intake centers for homeless families and encampments filled with entire communities supporting each other through their shared experience of homelessness and displacement. Despite unprecedented resources, poverty rates in the District of Columbia are rising. And nowhere is this issue exemplified better than in the District’s affordable housing and homelessness crises. Though the District committed to ending veteran homelessness by the end of 2016 and chronic homelessness by the end of 2017, 2018 saw an increase in both types of homelessness. Prince George’s County, Maryland has been informally dubbed “Ward 9” for its increasing presence of displaced Black and Brown Washingtonians, as over 40,000 Black and Brown residents have left the District, unable to afford the rising cost of living.

It is tempting to search for the silver bullet to solve these crises. However, there is no easy and no single solution.

Ending poverty will take an overhaul of all of our systems: housing, education, healthcare, employment, transportation, food, childcare, banking, policing, and justice. These systems are deeply entrenched in our society, and many took shape during the periods of slavery and Jim Crow. Their legacies of racism still endure, determining who can access opportunity, and who is shut out.

These systems are also intimately connected to each other, as a person’s housing stability affects their ability to stay healthy. A person’s employment impacts their ability to access healthy food. A person’s physical and mental health impacts her financial stability and the emotional health of her family. You cannot interview for a job with a child in tow, but you cannot afford childcare without a job.

We will not successfully solve these problems unless we address them in a comprehensive way and examine how every proposed policy initiative will advance equity and build wealth, access, and opportunities for marginalized communities.

Just as there is no single solution to end poverty, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to solving our housing and homelessness crises. Rather, the city needs diverse, flexible options that meet the unique needs of all its families, individuals, seniors, and youth. And fundamentally, our country needs to recognize housing as a human right and fully support and fund a universal right to housing.

Though the District is increasing funding for affordable housing, it is not keeping pace with the loss of affordable units, nor are the funding levels meeting the full need for housing.

In the District of Columbia, and in many large cities throughout the world, housing has become a hot commodity and housing developers have seen profit windfalls over the past few decades as cities have become more desirable locations for young professionals to locate. As a result, the private market has stopped producing affordable units and is producing fewer units suitable for families, particularly for our lowest income households. Federal divestment from public housing and underfunding of subsidized housing has created an enormous gap between the availability of affordable units and the growing need for those units.

Affordable housing is considered one of the top issues affecting the District. Yet in 2018, despite the District’s $14 billion budget, housing accounted for roughly three percent of the District’s spending, highlighting the gap between our supposed priorities and the funding that supports them.

There are a few examples that demonstrate this gap. There are over 27,000 District households making zero to 30 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI) who are paying more than half of their income in rent. Since 2015, the District has planned for or produced only 3,000 units for this income bracket. Though there are nearly 40,000 families on the Housing Authority waitlist for housing, the Fiscal Year 2019 proposed budget adds only 59 vouchers to move families off of the DC Housing Authority waitlist into permanent housing and 16 vouchers for seniors.

In 2015, the District published a strategic plan to end homelessness titled Homeward DC. This plan outlined the investments necessary to make all forms of homelessness rare, brief, and non-recurring. Yet the Mayor and Council only fully funded the plan in its first year, 2016; as a result, the District has failed to meet its commitments to end homelessness in the time outlined.

There is a spectrum of housing needs we must meet without delay.

The urgent housing needs the District must address range from homeless services to strong rent control, housing production, and home purchasing options that all contribute to a diverse and flexible housing ecosystem. We need ample funding to support homelessness and eviction prevention so that people do not enter homelessness in the first place, as well as robust outreach services to connect residents experiencing homelessness with housing, employment, and healthcare services. The District must create stable, safe, and dignified safety net shelters that support people through the trauma of experiencing homelessness. And we need to move families and individuals from shelters to permanent housing.

On the rental market, we must eliminate barriers like criminal background and credit checks so that voucher holders and low-income tenants can find rental options. We must preserve our existing stock of affordable housing—including public housing. And we need strong rent control laws so that landlords do not have financial incentives to displace their current residents to increase prices for future tenants or sell their properties for huge margins. Because the private rental market has stopped producing affordable units, we need to invest to create these truly affordable rental options. As home values have doubled and sometimes tripled in price, we need home purchase assistance programs so that low and middle-income households have opportunities to purchase homes.

Funding for these initiatives needs to be examined through a needs-based lens using a solutions-oriented approach. Rather than comparing our housing budget to previous years, we must compare funding levels to the full need and ask whether we are really solving the problem rather than incrementally meeting small portions of the full need. This fiscal year, our District government realized that our Metro system was in jeopardy and needed $178 million to solve the problem. They worked to increase revenues to meet Metro’s full need. Similarly, our government needs to recognize the full scope and scale of our housing crisis and work to prioritize housing affordability and fund the full need, even if it takes increasing revenue.

In a city as prosperous as ours, no one should be living and dying in a tent on the street.

No one should be living with raw sewage flowing through their basement. No one should be denied shelter because they do not have the proper identification documents. And no one should be priced out of their generational home.

In his 1964 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Dr. King said, “There is nothing new about poverty. What is new, however, is that we have the resources to get rid of it.” Dr. King recognized the material prosperity of our country 54 years ago. And today in D.C., our $14.5 billion budget is bigger than any time in our history. With a robust tax base and thriving economy, D.C. has the necessary resources to innovatively address poverty and the District’s enduring social, racial, and economic inequalities. It is time we use our resources to truly solve the District’s problems.

Back to list of essays

Achieving housing affordability in D.C. requires multiple strategies

By (W.) Chris Smith, WC Smith

Amid the District’s economic success over the past two decades affordable housing has become one of the city’s greatest challenges. As the population has increased, so have housing prices, making it difficult for households to rent or buy housing, especially for those at the low end of the income scale.

Politicians, think tanks, developers, and activists are all asking the same questions about how to provide enough affordable housing to meet the demand. It is unlikely that there is a single policy that will greatly increase the supply of affordable housing in the District. For starters, there is a difference between preserving existing affordable housing and creating new affordable units. Both are necessary pieces of an affordable housing strategy, but they require different approaches to make them happen. Furthermore, “reducing housing inequities and creating a more inclusive D.C.” requires going beyond simply increasing the number of affordable units available: equity and inclusivity require investments in workforce development, educational improvements, additional mental health services, increasing public safety, and concerted efforts to prevent displacement, among other things.

Equity and inclusivity: How did we get here, and what are we trying to solve?

The background is, of course, complicated, involving the history of redlining and discriminatory housing laws, urban renewal, the lack of a housing ‘pipeline’ (as very little new housing was built in the city during the 1970s and 1980s), the population surge, and zoning limitations, among other factors.

Clearly, the limited housing supply at all levels is a central part of the problem. The District’s population has been increasing by about 10,000 people a year over the past ten years, and there is additional demand for housing from households that find themselves priced out of the city. Even though more new housing was built between 2001 and 2010 than in the previous 30 years, according to the Urban Institute, the housing market has not been able to keep pace with this population growth. Despite strong growth in many neighborhoods, only 23,000 new units were added in the last five years (with a net growth in housing units of only around 20,000 as some units were repurposed).

The constricted market through both zoning and overly burdensome regulations significantly reduces the housing affordability in the District, for all income brackets. If we built significantly more housing, would housing costs drop?

The problem of limited supply is a nationwide issue. Recently, the CEO of Redfin, an online real estate broker, recently said that restrictive zoning laws are a major contributor to the current lack of housing inventory. “These laws, supported on the left and right are fiercely defended by well-meaning neighborhood associations that have sometimes started to act as a cartel to limit housing supply and keep prices high,” Kelman said on a call with analysts, according to GeekWire. “It’s these laws, not market forces, that prevent builders from replacing parking lots, stripmalls and single-family homes with affordable high-density condos and townhouses.”

Even if the District could loosen the restrictions on supply, there is still the question of how many affordable units are needed to solve the problem. And affordable at what levels? Should we be providing affordable options to households at many income levels or should be focusing on workforce housing or on housing for households making less than 30 percent of Area Median Income (AMI), who tend to spend more than half of their income on housing? The DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) estimates that it would require $2.6 billion to provide 30,000 deeply affordable units for the 27,000 households with incomes below 30 percent of AMI. However, the DCFPI study also states that “higher-income groups (50 to 60 percent of the area median income) are relatively well-served by the District’s non-subsidy housing tools, such as real estate development and inclusionary zoning.”

This has not been the experience of WC Smith. Every time we open a new affordable apartment building, for example Archer Park in Congress Heights or Juniper Courts in Petworth, we have a long list of people interested in the affordable apartments—certainly more than we can serve. Most of the units we offer are limited to households earning up to 60 percent of AMI. Given the influx of applications, it does not seem to us that households earning the 50 to 60 percent of AMI are adequately served.

Looking beyond affordability

More broadly, is the problem lack of affordable housing, or it is lack of opportunity, inadequate education, or some combination of these and other factors? If so, how does the city address those issues that stretch beyond construction and preservation of affordable housing?

At least among those in our trade—developers—there are different trains of thought. Some developers feel that instead of channeling funding to the lowest income neighborhoods, resources should be spread to into more prosperous areas, allowing low-income households more opportunities to improve their social well-being by the opportunities offered in these neighborhoods, including better schools, better services, and more job opportunities.