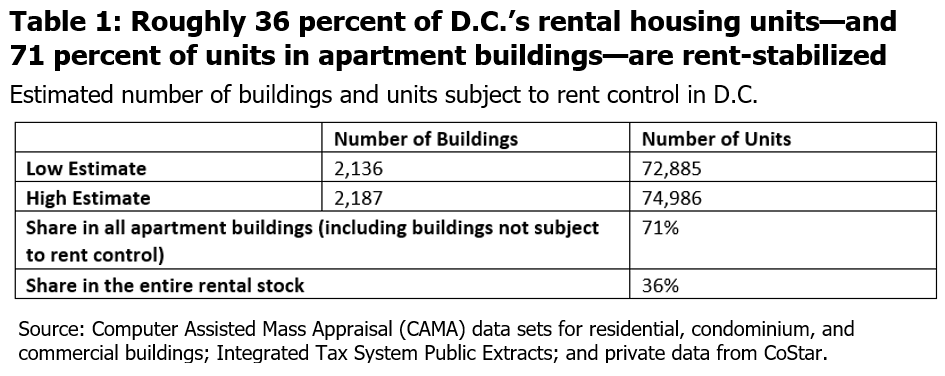

Over 35 years after the enactment of the Rental Housing Act of 1985, the number of rent-stabilized units in D.C. has held up relatively well. According to D.C. Policy Center estimates based on publicly available tax data and proprietary data from CoStar, D.C. currently has close to 75,000 rent-stabilized housing units spread across almost 2,200 buildings (Table 1).[1] This is equivalent to 71 percent of all units in rental apartment buildings[2] and 36 percent of all units that are currently being rented.[3]

When the Rental Housing Act was enacted in 1985, we estimate that there were at most 85,000 rent-stabilized units in 3,158 buildings.[4] Some of these units have been lost when the buildings were converted to condos or co-ops, including conversations through TOPA.[5] This means that the total leakage out of the rent-stabilized stock has been less than 15 percent over nearly 35 years. This is a much lower leakage rate than other jurisdictions with stricter rent-control policies. For example, only ten years after San Francisco extended its rent control laws to buildings with fewer than 5 units, the number of rental units in such buildings declined by 15 percent, and the number of tenants in these buildings have declined by 25 percent—a much swifter decline than D.C. has seen in over three decades.[6]

D.C.’s stock of rent-stabilized units has remained so steady in part because the law prioritizes rent stabilization over strict price controls. The Rental Housing Act’s goal is not to create or preserve affordable housing, but to protect tenants from rapid, unreasonable increases in their rents. This might seem like a minor distinction, but it’s an important one to make as we consider the law’s future.

The Rental Housing Act allows landlords to increase rents to cover costs that grow faster than the cost of living, while providing assurances to tenants that year-to-year increases in their rents will be within reason. The District’s CPI + 2 percent rent increase allowance has been the primary reason why the city’s rent-stabilized stock has been resilient.

If the District’s goal is to maintain the size of the city’s rent-stabilized stock, the answer is to relax the rules that govern rent increases, not tighten them. This is especially important in an environment with rapidly increasing operating costs both because of market forces and because of regulatory impositions. The more rents are allowed to rise, the higher the landlords’ investment in these buildings, and the lower the temptation to take them out of the rental market entirely by converting them into condominiums.

Turning the District’s current rent stabilization program into a strict rent control regime will ultimately frustrate affordability goals. The city has firsthand experience with how expensive affordability can be: D.C. provides substantial subsidies for the creation and preservation of affordable housing units in addition to a combination of federal and local rent subsidies. These, when combined, account for more than $150 million in the District’s annual budget. If the District were to go beyond an extension of the current rent stabilization law and enact stricter rent control laws, absent any other supports, the city would simply push the cost of subsidizing affordability from the government’s balance sheet to landlords’ balance sheets—creating what is essentially an unfunded mandate. And the market will not passively internalize this, and the mostly likely outcome will be fewer, and not more, rent-restricted units.

About the data

Because D.C.’s rent stabilization ordinance operates through both buildings (based on the age of the building) and owners (through the number of rental units owned), it is difficult to know exactly how many units are actually subject to the law. The estimates for the number of rent-stabilized units in D.C. are based on a combination of data sources which include publicly available data from three separate Computer Assisted Mass Appraisal (CAMA) data sets for residential, condominium, and commercial buildings; Integrated Tax System Public Extracts; and private data from CoStar. The combined data was filtered by number of units and year-built information that met the criteria from the Rental Housing Act, in order to obtain the estimate for the District’s rent-stabilized housing stock. For buildings that did not have the number of units listed in the CAMA datafiles, we used the CoStar database. If the CoStar data did not have the information either, we used the number of different addresses in the same building as the unit count. The higher estimate for the number of units includes those for which the year-built information was not available, whereas the lower estimate does not.

This article is adapted from Dr. Sayin’s November 2019 testimony, with updated data.