On Friday, September 16, 2022, Executive Director Yesim Sayin testified at the D.C. Council Committee of the Whole Hearing on Bill 24-570, the “Schools First in Budgeting Amendment Act of 2021.” You can read her testimony below, or download a PDF copy.

Good morning, Chairman Mendelson and members of the Committee of the Whole. My name is Yesim Sayin, and I am the Executive Director of the D.C. Policy Center—an independent non-partisan think tank advancing policies for a strong, vibrant, and competitive economy in the District of Columbia. I thank you for the opportunity to testify on the staff draft version of Bill 24-570.

The D.C. Policy Center testified on bills 24-570 and 24-571 in January 2022. Three of the concerns we expressed during that testimony – implementing an inflationary adjustment in a high inflation year, baking the existing inequities into the system, and basing calculations on proposed budgets and not actual spending—remain under the staff draft. Today, we have two additional concerns, one related to new language in the staff draft, and the other stemming from new information we learned since January.1

New language in the draft regarding baseline budgets and the potential of a fiscal cliff

The staff draft has added new language to include in the baseline school budgets all sources of funds—local and federal—that would have to be grown by the budget growth rules in the legislation. The staff draft requires that this change be implemented in FY 2024, which means, if the bill is enacted, these changes will impact school year 2023-24 budgets.

The timing of such changes would create a significant fiscal problem. School year 2022-23 budgets have benefited from one-time federal and local resources that would now have to be included in the baseline without the guarantee of recurring revenue in the approved budget and financial plan. This year, schools received federal ESSER funds that will expire in September 2024 and one-time local funds (Mayor’s recovery funds) that are not in the approved financial plan for fiscal years 2023-26.

Consider, for example, Mayor’s recovery funds, which, according to DCPS, sent $45 million to school budgets, or about 5 percent of total funds budgeted at schools this fiscal year.2 Under the staff draft, next year, the baseline school budgets would have to include this amount plus the growth formulas included in the bill. If the federal grants and other sources remain the same next year, formula funding going to DCPS would have to increase by 4.7 percent just to make up for the loss of Mayor’s recovery funds.3

Perhaps, in the next school year, the federal ESSER funds can be shifted from other uses within DCPS to schools to close this gap.4 But ESSER funds are already supporting school budgets by $21 million to account for enrollment fluctuations and $6 million for accelerated learning support.5 Shifting even more of the ESSER funds to school budgets will make the fiscal cliff even bigger in subsequent years.

New information and the potential of funding inefficiencies

In July 2022, the D.C. Policy Center published a new analysis of school enrollment trends and provided three potential enrollment trajectories.6 Our analysis showed that even under the best-case scenario, school enrollments will likely remain below current levels over the next five years, at around 89,000 students, and under the worst-case scenario, enrollments could decline by 6,000. Importantly, these changes will not hit every grade band and every school the same way. Even under the best-case scenario, we projected that enrollments at the elementary level will decline, driven by fewer births and lower demand for public schools.

If these projections hold true, DCPS might be forced to keep constant the budgets of schools that are losing enrollment. If students move from one DCPS school to another, budgets in other schools might have to be increased even when the overall universal per pupil formula funding remains the same. If students move from DCPS to charters, DCPS will lose per pupil formula funding, but could be prevented from reflecting this change in school budgets. Or, if enrollments decline because entry level grades do not attract as many new students as projected, DCPS would have to fund a non-existent student.

We don’t know what enrollment projections will be used for next year’s budget projections. But we can examine what the bill’s impacts might have been had it been in place when the current year’s budgets were being developed.

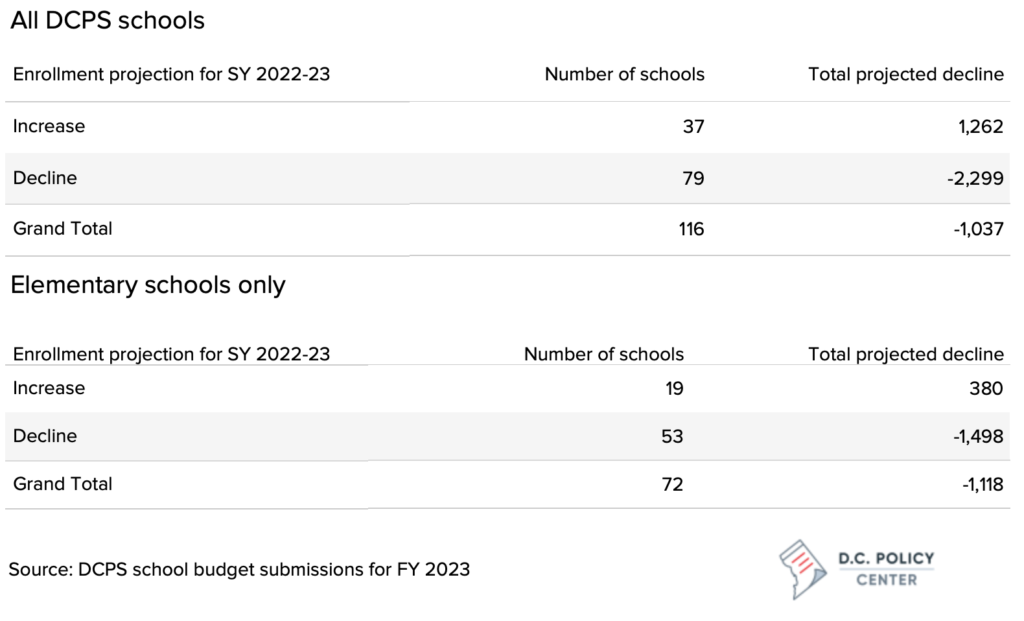

The enrollment projections used for the SY 2022-23 DCPS school budgets show that this year, across all DCPS schools, 79 schools are projected to experience a decline in enrollment, collectively losing 2,299 students. Among elementary schools, which are more likely to continue losing enrollment per our research, 53 out of 72 schools are projected to lose a combined total of 1,498 students.

Figure 1 – Projected enrollment changes in DCPS schools

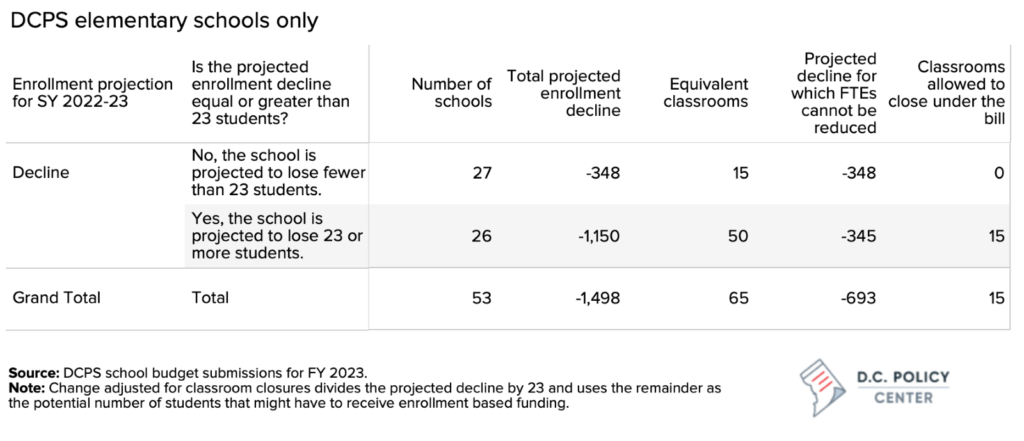

What might be the cost of budget stability under the staff draft of Bill 24-570? The draft stipulates that if a school loses enrollments large enough to close a classroom, this could be deducted from the budget calculations. To build an example of what that might mean for funding under the proposed bill, we only looked at elementary schools and used a classroom size of 23, which is the mid-point of maximum class sizes allowable in the most recent WTU contract.7

Of the 53 elementary schools that are projected to lose students this school year, 27 are projected to lose fewer than 23 students (for a total of 348 students). That is the equivalent of 15 classrooms, which will have to be kept open and funded under the staff draft of Bill 24-570. In addition, 26 schools are projected to lose more than 23 students, with a combined decline of 1,150 students, which is the equivalent of 50 classrooms. But under the staff draft, they would be allowed to close only 15 classrooms. Thus, Bill 24-570 creates opportunity costs as funding must be allocated to keep 35 empty classrooms open instead of being allocated to students where they are and their present needs. The actual cost would depend on whether the students are changing schools within DCPS, shifting to charters, or exiting the public school system.

Figure 2 – DCPS elementary schools with declining enrollments and projected number of classrooms that must be reduced

To put it a different way, across these 53 elementary schools, DCPS could have lost its universal per pupil formula funding for 693 students if these students exited out of DCPS; but, under this bill, DCPS would still have to budget for them at their initial schools. Or DCPS would have had to budget for them in two different schools if they transferred from one DCPS school to another.

While budget stability is important, its fiscal implications could become significant during a period of enrollment loss, especially when current budgets are already relying on one-time revenues that cannot be guaranteed in future years.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I welcome any questions.

Endnotes

- The staff draft has attempted to address one problem: The bill now requires the District of Columbia Public Schools (DCPS) to separate its budget into not three, but four buckets: Central Administration, Local Schools, School Support, and School-Wide. The addition of School Supports to account for centrally organized services that serve all schools and students is an improvement over the previous draft since this change allows DCPS to continue fund centrally key supports to schools. The staff draft limits Central Administration and School Support to a combined 15 percent of the total DCPS budget.

- According to DCPS, school year 2022-23 school budgets benefited from $45 million in Mayor’s stability funding, $154 million in targeted stability funding and $672 million in enrollment-based funding. However, an examination of the submitted school budgets show approximately $10 million in Mayor’s recovery funds explicitly budgeted at schools.

- The calculation assumes an inflationary adjustment of 5 percent bringing the required gap to $47.5 million. This is 4.7 percent of local funding DCPS received in school year 2022-23.

- Out of the three rounds of ESSR funds, DCPS is receiving $303 million and of this amount $53 million has already been spent—some at programs budgeted at the central office and some at schools (available at OSSE ESSR Dashboard available at https://osse.dc.gov/recovery). An examination of ESSR spending plans (available at https://dcpsbudget.com/budget-data/central-office-budgets/covid-19-agency-budget-additions/#:~:text=DCPS%20received%20%2487M%20under,2022%20(FY22)%20as%20well.&text=%2426%20million%3A%20School%2Dbased%20academic%20and%20social%20emotional%20acceleration) show that at least $47 million has already been budgeted directly at schools.

- This information is available at https://dcpsbudget.com/budget-data/central-office-budgets/covid-19-agency-budget-additions/.

- Coffin, Chelsea & Julia Rubin (2022) Declining births and lower demand: charting the future of public school enrollment in D.C. D.C. Policy Center, Washington D.C. Available at https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/enrollment-decline/

- Section 23.13.1 of the WTU contract that covers 2016 through 2019 limits maximum class size to 20 for Kindergarten through Grade 2, and to 25 for Grades 3 through 12.