In many ways, Washington, D.C. has become a much safer city in recent years. Over the last 10 years, we’ve seen a slow but steady reduction in violent crime, which further dropped by 22 percent in 2017 compared to the previous year. However, one type of violent crime – sexual abuse—has followed a slightly different pattern.

“Sexual abuse” (or “sexual assault”) refers to sexual contact or behavior that occurs without explicit consent of the victim. It can take many different forms, including rape, unwanted touching, or forcing a victim to perform sexual acts. In D.C., crimes involving rape and sexual assault are categorized as sexual abuse, defined using varying degrees of severity depending on the malicious intent of the crime and whether actions by the accused can be classified as a “sexual act” or “sexual contact.”

Using data from Open Data DC, this article examines recent trends in sexual assaults the District, including where such crimes are reported and how the city has responded.

Reported sexual assaults in the District of Columbia have increased over the past decade

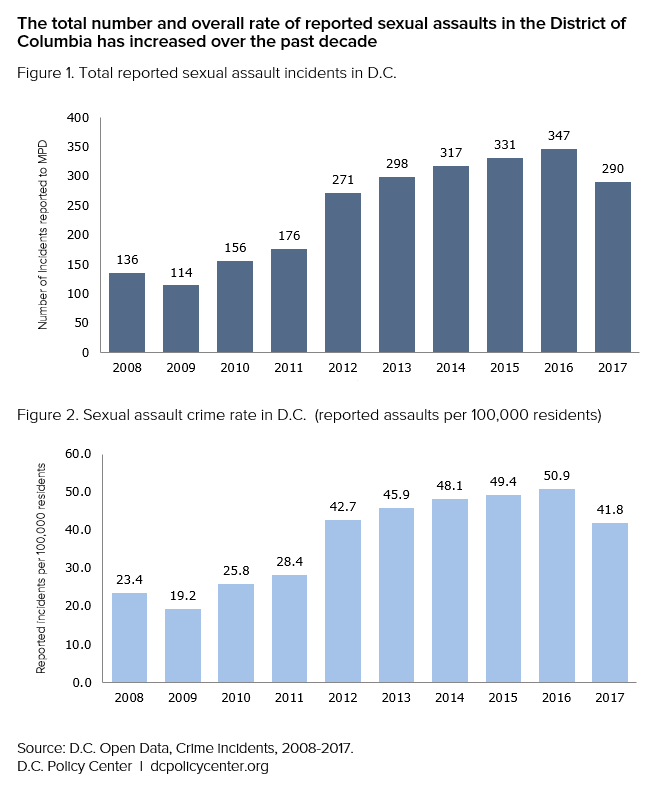

In each year between 2009 and 2016, more sexual assaults were reported compared to the previous year. Below, Figure 1 shows the total number of sexual assault crimes reported to the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) from 2008 to 2017. Reported sexual assault crimes peaked at 347 in 2016, tripling the count of 114 in 2009. In 2017, however, the total count of reported sexual assault crimes dropped by about 16 percent compared to its peak in 2016.

To factor in population changes over time, Figure 2 presents the rate of reported sexual assault crimes for the same period, expressed as the number of such reports per 100,000 residents. Similarly, the sexual assault crime rate reached its highest point of 50.94 per 100,000 residents in 2016, before dropping to 41.79 last year.

The sharpest uptick in reported sexual assaults in D.C. happened in 2012, when the sexual assault rate jumped to 42.7 per 100,000 residents from the 2011 rate of 28.4. Since then, the rate has increased by about 4.5 percent each year until 2017.

However, several factors make it difficult to know if the steady rise of sexual assault crimes reported over the last decade reflects a proportionate increase in the number of assaults actually committed. First, an increasing number of reported sexual assaults is not necessarily a bad thing, especially since it is one of the most underreported crimes. In line with many other parts of the country, the reporting of sexual assault crimes in D.C. has improved in recent years. An increasing number of survivors are reporting their experience to the police: According to Lois Frankel, a former director at the D.C. Rape Crisis Center, more victims seeking counseling at the Center are reporting their rapes. In addition, the Metropolitan Police Department, which came under criticism for allegations of mishandling sexual assault cases not too long ago, has also made significant improvements in classifying, documenting, and processing such cases.

Does the lower number and rate of sexual assaults in 2017 represent an actual decrease in assaults? It’s hard to know. One of the challenges with interpreting sexual assault statistics is that so many assaults are unreported, so a decrease could simply mean that fewer victims are reporting their assaults. Furthermore, as with other offense data, sexual assault statistics in the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) database can change, among other things, if the classification of the offense changes or if assaults are reported later. Therefore, the initial sexual assault statistics for 2017 should be interpreted with caution.

How MPD practices around investigating sexual assault have changed since 2008

Over the past decade, MPD has dramatically improved its approach to investigating sexual assaults. The department began making changes to adopt a more victim-centered approach in 2008, but a 2013 Human Rights Watch (HRW) report titled “Capitol Offense: Police Mishandling of Sexual Assault Cases in the District of Columbia” was a very public further catalyst for change.[1] In response to the HRW report, the D.C. Council also passed the Sexual Assault Crime Victim’s Rights Amendment Act (SAVRAA) in May 2014, which significantly strengthened the rights of sexual assault survivors. Specifically, the law grants survivors the right to have a confidential, independent community-based advocate present during a medical and forensic exam and law enforcement interviews, to have their sexual assault evidence kits processed within 90 days of submission to the lab, and to be informed of the results of toxicology and DNA testing.

Since then, a series of independent expert reports have been conducted to evaluate and audit the implementation of SAVRAA, and to identify any additional improvements needed, finding that the spirit and intent of SAVRAA have been implemented across law enforcement and other response agencies involved. Shortly after SAVRAA became law, an external independent review in 2015 found that despite staff and resource issues, MPD detectives were working around-the-clock to ensure that sexual assault cases were fully investigated, and were done so through a victim-centered perspective.[2]

In short, the District has made significant improvements in the way it handles sexual assault cases, and it is plausible that these efforts have led to a decline in sexual assault crimes across the District. However, as noted earlier, it is too soon to know whether or not the 2017 data reported indicates a trend – either in terms of fewer sexual assaults committed or due to lower reporting rate. Furthermore, a number of barriers persist within the city’s criminal justice system, which may be dissuading victims from reporting.

Recently, the U.S. Attorney’s Office for District of Columbia (USAO) – the primary prosecutor for adult sexual assault cases in D.C., became the target of survivor and community frustration. During a Council hearing in February 2016, survivors testified that the USAO failed to maintain adequate and transparent communication with them throughout the prosecutorial process, leading them to describe their experience with the office as “one of torment.” An independent review of the prosecution process of sexual assault crimes in the District echoed these concerns, finding that “the process is vastly less respectful and meaningful than the USAO perceives it to be.” The report also found evidence that the USAO rejected warrants or declined to prosecute many cases—such as where a victim delayed in making a report, experienced mental illness, was transgender, or had a previous relationship with the suspect—in which common misperceptions around sexual assault potentially held by a judge or jury meant the case was less likely to succeed in court.

The prospect of an arduous, opaque, or even adversarial prosecutorial process can discourage many victims from reporting their experience. In fact, the perception of an unhelpful law enforcement system is the second most common reason victims choose not to report sexual violence. As a crucial component of the city’s response to sexual assault crime, the USAO should actively address the frustrations felt by victims, so as to encourage future victims to report sexual assault crimes.

Where sexual assaults have been reported in D.C.

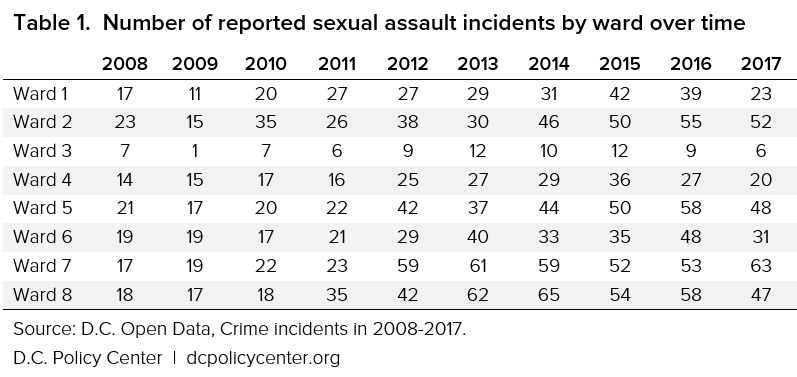

Some areas of the city are also much more likely to have sexual assaults reported than others. Using data from D.C. Open data, Table 1 shows the geographical distribution of sexual assault crimes by ward, from 2008 to 2017. The table reveals a stark disparity in the concentration of sexual assault crimes across the city, especially in the years after 2012.

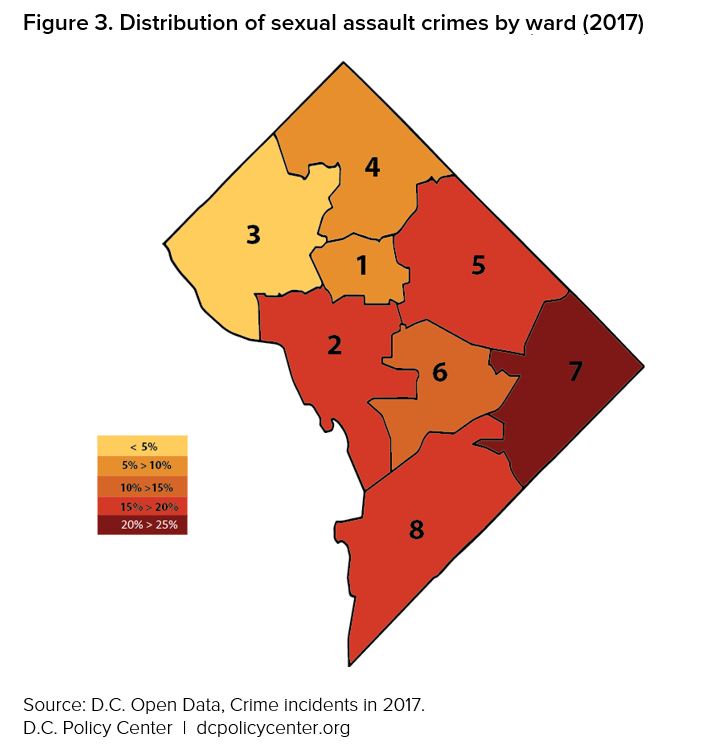

While the total number of sexual assaults dropped in 2017, the geographical distribution of such crimes remains unchanged; and continue to reflect the city’s economic disparities. Figure 3 illustrates the geographical distribution of sexual assaults in D.C. in 2017, estimated as the percentage of all sexual assaults by ward.

In 2017, the less affluent areas in the District – Wards 5, 7, and 8 – together witnessed nearly 55 percent of all sexual assaults across the city. Ward 7 and 8, where the median household income is less than one-third of that of Ward 3, continue to bear the brunt of sexual assault crimes. On the other hand, more affluent areas – including Wards 1, 3, 4, and 6 – continue to report relatively fewer sexual assaults in 2017. For instance, only 2 percent of all sexual assaults in the district last year took place in Ward 3, where the estimated median household income for 2016 was $116,341.[3]

This correlation between economic insecurity and sexual assaults is in line with existing research showing that poverty increases people’s vulnerabilities to sexual violence. Often times, sexual violence further disrupts survivors’ economic stability, creating a vicious cycle in which sexual violence and economic insecurity become mutually reinforcing. In addition, 7 out of 10 adult victims know their attacker prior to the assault, making it for difficult for survivors to seek justice, especially if they are in a dangerous situation.

What the data doesn’t show

When examining the current state of sexual assault crimes, data alone is not enough. To being with, the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that more than three-quarters of sexual assaults are not reported to the police, often due to fear of retaliation or belief that police will not believe them.

Furthermore, the MPD database for reported sex abuse statistics includes only the most serious sexual abuse cases, including First Degree Sex Abuse, Second Degree Sex Abuse, Attempted First Degree Sex Abuse and Assault with Intent to Commit First Degree Sex Abuse against adults.

Sexual assaults that occur on university campuses may also be missing from the MPD database; universities are required to report this information with the U.S. Department of Education under the Clery Act, but victims must make a separate report to MPD. In 2015, for instance, 21 students at George Washington University reported to the school that they had been raped. While this information was shared with federal education officials, only one of those rapes was reported directly to the police.

Finally, while the MPD provides abundant data on criminal offenses across the city, D.C.’s USAO offers little information about its prosecutorial process. Without information on the legal outcomes of sexual assaults in the District, it is impossible to accurately assess the changing landscape of sexual assault crimes. Currently, the District’s USAO is the only one in the country that is not required to provide aggregate criminal justice outcome data to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

The District’s uniquely bifurcated criminal justice system – divided between the locally controlled law enforcement agency and a federally designated prosecution and court system – means the Council has little control over the USAO. However, a lack of transparency around prosecutions and the court system that handles them can create setbacks for any progress made within our law enforcement agencies, including those generated through SAVRAA and other survivor advocacy efforts. Therefore, in line with their counterparts across the country, the USAO for the District of Columbia should also be required to share aggregated outcome data with the BJS.

About the data

Data on reported sexual assaults in D.C. are from D.C. Open Data, Crime incidents (2008-2017). For each year between 2008 – 2017, data was filtered and extracted based on offense type (“Sex Abuse”). Sexual assault rates for 2008-2016 were calculated using the respective annual population estimates (as of July 1) from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Population Estimates Program as reported by the OCFO; 2017 data was taken directly from the U.S. Census Bureau’s QuickFacts page.

There are sometimes inconsistencies between D.C. Open Data statistics and the numbers reported in MPD annual reports. According to MPD, sexual assault statistics, as with other offense data, are subject to change due to various reasons, including a change in classification, the determination that certain offense reports were unfounded, or late reporting. D.C. Open Data includes datasets from MPD’s Crime Mapping platform, and are updated frequently.

Notes

[1] An independent report later contradicted HRW’s specific assertion that MPD failed to document or investigate 170 sexual assault cases. However, this independent report did find that the HRW report led to improvements in MPD practices: “The HRW Report resulted in MPD’s re-evaluation of personnel, procedures, and practices in sexual assault investigations. Though MPD gradually improved procedures for handling sexual assault cases starting in 2008, the HRW Report accelerated the improvements. Many of the individuals and organizations that deal with victims of sexual assault on a daily basis—hospital nurses, prosecutors, and victim advocates—have seen significant improvements in MPD’s responsiveness, teamwork, and victim-centered approach since HRW issued a draft report in May 2012.” (pp 1-2)

[2] In April 2017, Mayor Muriel Bowser introduced a proposal to amend SAVRA. In addition to clarifying the rights of victims and the duties of law enforcement official, the proposal would expand sexual assault victims’ rights have an advocate present, provide victims a right to information about their cases from prosecutors, and extend the law’s coverage to victims between 12 and 17. The bill is currently under council review.

[3] Considered the densest area of the city, Ward 2 also stands out for having higher concentration of reported sexual assaults between 2008 – 2017. For instance, in 2017, Ward 2 accounted for 18 percent of reported sexual assaults in the District – a similar rate as Ward 5.

Feature photo: A visualization of crime in D.C. from the 2012 exhibition DC Zeitgeist III: “Too Much Information?” at the District of Columbia Arts Center. Photo by Ted Eytan (Source).

Shirin Arslan is an economist who specializes in gender analysis in economics and workers’ economic security. She holds a master’s degree in economics from American University and B.A. in Economics from Virginia Commonwealth University. Learn more about her work at shirinarslan.com.