The economic effects of the coronavirus pandemic have been dramatic and unprecedented, as cities and countries shut down large swaths of their economies to control the spread of the virus, and consumer demand has fallen due to stay-at-home orders, rising unemployment, and general economic uncertainty.

As previous recessions and other economic shocks have taught us, small businesses will generally experience the most severe impacts, as they are less likely to have the reserves, resources, and capacity to shut down for long periods, change their business plans to shift entirely to remote work, or simply absorb steady losses until the economy recovers. A national survey of more than 5,800 small businesses through the network Alignable found that 43 percent of respondents had temporarily closed by the end of March, including 54 percent in the mid-Atlantic region. In D.C. in particular, much of the city’s start-up activity has taken place in high-contact sectors, such as accommodation and food services, that have seen their revenues fall to one fifth (or less) of pre-pandemic levels.

In mid-March, after the District had seen its first official COVID-19 case and as the city began to restrict various services to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, the D.C. Policy Center shared a questionnaire about how small businesses are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. These questionnaires, distributed primarily through industry groups and other existing networks by email, were not meant to be representative surveys. Instead, they were an opportunity for small businesses to tell us, in their own words, their concerns about their future in an uncertain economic and public health environment. We received over 200 responses from small businesses based in D.C. and in the broader metropolitan area. By pairing these qualitative responses with national surveys and economic data, we can to provide a look at how D.C. businesses are experiencing the COVID-19 crisis, and what they need to survive and recover in the months ahead.

Overwhelmingly, small businesses’ immediate concerns were about loss of customers and revenue, and the need for immediate assistance for rent, payroll, insurance premiums, and other basic expenses. According to research from the JP Morgan Chase Institute, 50 percent of U.S. small businesses only have enough of a cash buffer for two weeks or less, and only 40 percent have enough for three weeks or more. Access to capital in an emergency can already be a challenge for small businesses, especially those owned by people of color, as they are more likely to lack the resources, capacity, and existing relationships to traditional lenders and other sources of funds that larger businesses can turn to in a crisis.

While some small businesses have been nimble in responding to changing conditions, such as restaurants shifting to grocery delivery, or distilleries producing hand sanitizer, national consumer spending data suggests that the recent rise in spending on ecommerce and delivery services is unlikely to entirely make up for the losses of in-person revenue for brick-and-mortar businesses. This analysis explores small business owners’ concerns and priorities across several key industries that have been hardest hit to date, as well as how the impacts of the pandemic and the economic shutdown could ripple outward.

Ben’s Chili Bowl interior on March 19, 2020 (Source: Ted Eytan)

Small businesses’ role in D.C.’s economy

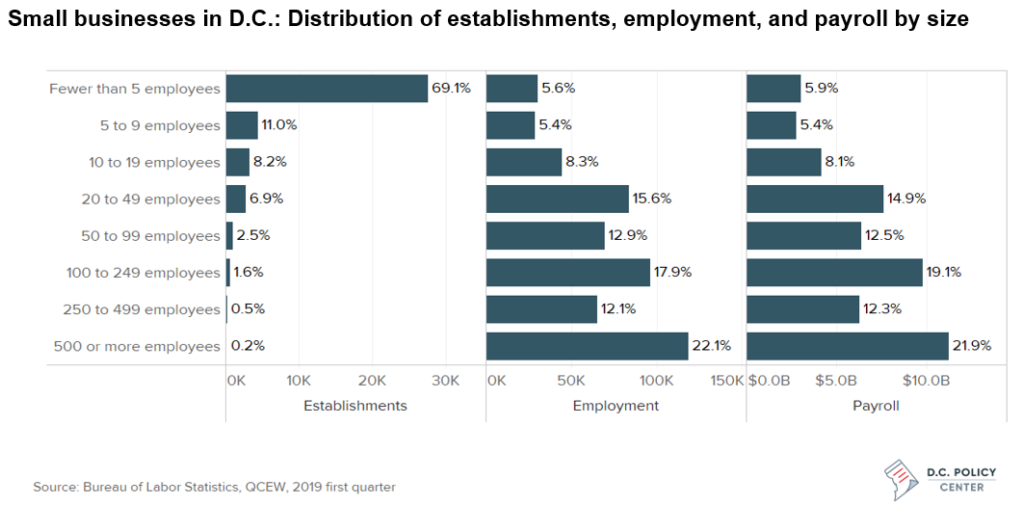

The number of small businesses in D.C. varies depending on which definition is used, as well as which data set. The chart below, which uses administrative data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, shows how the footprint of differently-sized businesses varies by number of establishments, share of employment, and proportion of payroll. For instance, very large businesses with 500 or more employees make up only 0.2 percent of establishments in D.C., but employ 22.1 percent of workers. Meanwhile, 69.1 percent of all establishments in D.C. are very small businesses with fewer than five employees, but because of their small size, they only employ 5.6 percent of the city’s workers.

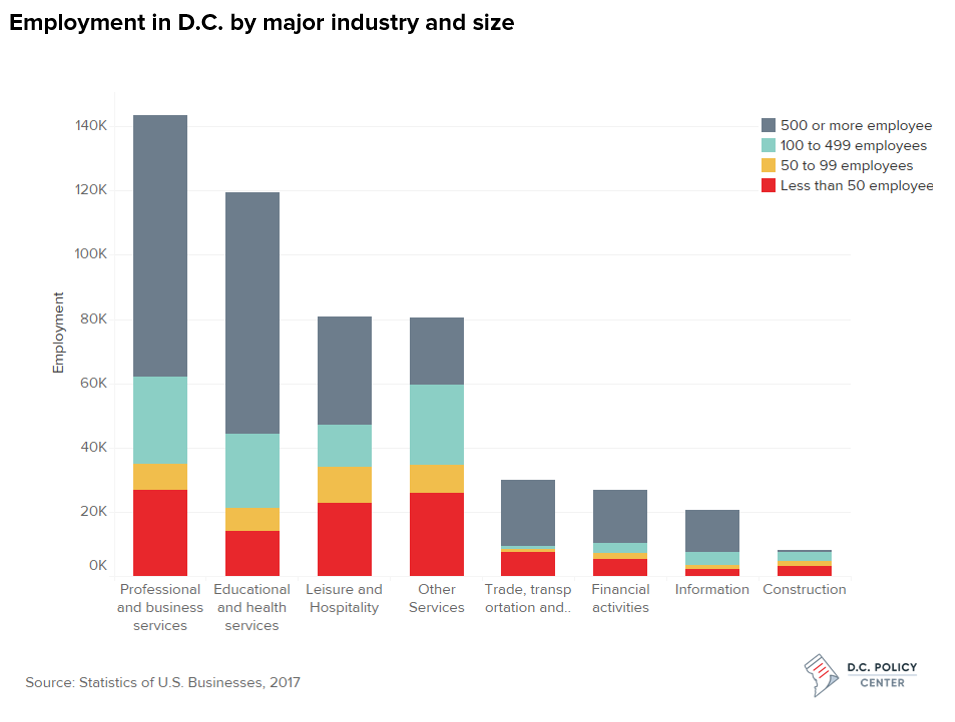

Across all business sizes, the top industry in D.C. by employment is Professional and Business Services, with 33.1 percent of the workforce, followed by Education and Health Services, which employs 23.4 percent of the workforce. Small businesses employment is concentrated in two industries: Professional and Business Services, and Leisure and Hospitality.

However, when looking at smaller businesses with fewer than 100 employees, the top categories also include Leisure and Hospitality—one of the industries hardest hit by the pandemic—and “Other Services,” as shown in the chart below. Construction is almost entirely composed of smaller businesses, while Financial Services has a relatively large share of both very large businesses (more than 500 employees) and very small businesses (fewer than 50 employees).

How COVID-19 is affecting different industries

Unsurprisingly, the types of small businesses that have been hardest hit by falling demand are “high contact” businesses that rely on in-person services—including many that have also closed in response to official orders in the interest of public health. Mayor Muriel Bowser declared a public health emergency in the District of Columbia on March 11, and on March 16, the D.C. government closed restaurants and bars for sit-down service, although many businesses had already experienced waning demand before official closures. As of publication, the public health emergency is currently in effect through May 15.

National data suggests that employment losses have been most severe so far for small businesses in retail, food services, personal services, arts and entertainment, and hospitality—all key sectors of D.C.’s economy. While there have been less severe immediate impacts among professional services, finance, and real estate businesses, as this analysis will explore, the exposure of these sectors to negative economic effects can increase as the crisis continues. Among the small businesses surveyed last month through Alignable, three-quarters said they do not have enough cash on hand to cover more than two months of expenses.

Since our questionnaire was distributed, sick leave, unemployment benefits, and grants and loans for small businesses have been expanded at the District and national level. But as the length of closures and distancing measures necessary to mitigate COVID-19’s effects increase from weeks to months, more impacts will be felt across more industries. “Right now we are not even sure if we will be able to bounce back after all this,” one respondent told us. “I do not want to lose these great employees that we have trained over the years,” wrote another.

Coffee and hand cleaner at Compass Coffee on March 30, 2020 (Source: Ted Eytan)

Restaurants, bars, and nightclubs

Just over half of the city’s restaurants have remained open since officials ordered the shutdown of dine-in services in mid-March, according to the Restaurant Association of Metropolitan Washington (RAMW). Those that are open are operating in a modified fashion, offering some form of takeout or delivery. In addition, some restaurants, bars, and even breweries are also turning to creative approaches such as providing groceries, toilet paper, or hand sanitizer as additional options.

Across the board, however, the shift to solely takeout and delivery has not begun to replace the loss of sit-down services: Among D.C. restaurants that are open and offering modified services, revenues are at least 80 percent lower than what they were a year ago, according to RAMW.

One respondent told us that by late March, all but one of their handful of locations had closed, and they had laid off the vast majority of their employees. “[I’m] worried about their wellbeing,” they told us, and “concerned we will not be able to pay rent and health insurance premiums due at the end of the month.”

“I am also worried that there isn’t enough support for businesses and restaurants that want to take their work online,” another respondent wrote. Industry data suggests that fast casual restaurants that already had robust online ordering have been in a stronger position in this new environment. But small independent businesses that did not have online ordering infrastructure set up would now need to set up such a system, often while also operating with a skeleton crew.

Meanwhile, many other restaurants—about four in ten—have closed entirely, whether due to financial difficulties, to protect workers, or because their infrastructure or approach does not work with a takeout-and-delivery model. D.C. CFO Jeffrey DeWitt estimates that among the roughly 40 percent of restaurants that have closed due to the pandemic, only half will reopen within the next year or so. Many establishments also not sure what reopening will look like, once shut-down orders are eventually lifted and sit-down service begins again.

Hospitality and tourism

While the hospitality industry has been a significant source of growth for D.C. in the past, it is also very sensitive to both broader economic conditions and specific events. Nationally, hotel occupancy rates have been falling since mid-March, and are now at historic lows as states and cities continue stay-at-home orders and businesses cancel travel.

Hotels in D.C. are still allowed to remain open and offer rooms, but conferences or other events that would violate D.C.’s rule against large gatherings are not allowed. Occupancy rates in the D.C. region have fallen to 18.3 percent, according to data firm STR, similar to other metropolitan areas such as New York City and Miami, although recent numbers from the D.C. CFO suggest that this number could be even lower. For context, in early 2019, when area hotels experienced a “rough” first quarter due to the government shutdown, STR reported that the average occupancy rate fell to 50.5 percent in January, and was 73.5 percent by March.

Other industries related to tourism and hospitality have seen revenue fall significantly, both due to consumers and businesses cancelling travel plans and government orders closing many non-essential businesses and restricting large crowds of people in order to constrain the spread of the virus.

The Wharf in 2017 (Source: Ted Eytan)

Retail and ecommerce

Across the country, grocery stores and many other food retailers experienced a surge in demand in mid-March as people stocked up on supplies. While other industries were laying off workers, grocery stores have been hiring additional workers to meet demand, and to replace workers who are sick or staying home.

National credit and debit card data shows that grocery sales increased through March as people started to prepare for stay-at-home orders, often peaking toward the middle of the month. Many other types of retail also saw increased sales in the weeks leading up to stay-at-home and shelter-in-place orders, before falling dramatically. Home improvement stores have continued to see increased sales, as they have remained open as an essential service, and many households appear to be taking this time to tackle home improvement projects.

As with restaurants, online shopping may be able to keep some retail businesses on life support, but does not appear to have made up for the loss of in-person sales. The national credit and debit card data shows that “general merchandise and e-commerce,” which includes large companies and platforms like Amazon, Walmart, and Etsy, has increased, but overall shopping at brick-and-mortar is down—especially in fashion and apparel, where even large retailers are struggling.

View of D.C. in 2018 (Source: Ted Eytan)

Real estate and construction

Respondents in industries with particularly long timelines, such as real estate and construction, see additional delays in store even when different parts of the local economy begin to pick up again. One real estate developer was also concerned about supply chain interruptions, along with “tenant default[,] which [affects] our ability to maintain liquidity.”

Previously, respondents were also concerned that a pending stay-at-home order would half construction work, leaving worksites vulnerable to “theft, vandalism, and damage from the elements,” including water damage and mold. Another respondent highlighted the importance of building management personnel during stay-at-home orders: “We are responsible for the operations of the building, including security, electrical, mechanical and plumbing systems.”

However, when Mayor Bowser issued the District’s stay-at-home order at the end of March, the order did allow construction to continue as essential work. This has also been the case in Maryland and Virginia. Households in D.C. are also allowed “to hire contractors to perform maintenance and keep up their properties.” Generally, support businesses are also considered essential if they provide services necessary that are necessary to maintain the safety, sanitation, and operation of residences (including apartments and hotels) and essential businesses.

The D.C. government’s coronavirus guidance says that “real estate offices should close to all but minimum business operations, but individual agents can work from their homes,” and also continue to call and work with clients, including placing properties for listing online. Open houses are not permitted, but homes can be shown to a single potential buyer at a time.

Several respondents to our questionnaire cited their concern that tenants would be unable to pay rent on time, and that potential new clients would put off moves and other real estate decisions. Among residential apartment buildings, the National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC) found that the vast majority of renters are still paying rent, although some payments have been received later. In April, NMHC reports that 89 percent of rental households made a full or partial rent payment by the 19th of the month, compared to 93 percent in 2019. Data from Entrata, a property management software, also suggests that occupancy rates remain relatively steady, at 93 percent for conventional multifamily properties, although renewals have dropped to their lowest point in the past year (48 percent). Entrata reports that “many properties are taking on month-to-month leases and staying in wait-and-see mode rather than signing renewals at this point.”

View of NoMa on March 1, 2020 (Source: Ted Eytan)

Immediate needs: Cash, rent, payroll

With many small businesses facing dramatic loss of revenue, including shutdowns across the metropolitan area of indeterminate length, respondents to our questionnaire overwhelmingly said they needed financial support.

Asked what types of action from the D.C. government would be most helpful to support their business and workers right now, one respondent wrote: “Financial aid in the form of grants, incentives, no interest loans. Tax breaks and tax differ payments.” Another said, “Generous unemployment benefits including for independent contractors.” Many also wanted direct and clear information about the resource available. “Tell me how the grants are going to work,” one respondent said.

Emergency legislation in D.C., along with new federal supports, have expanded unemployment benefits for workers unable to work during the pandemic. Self-employed individuals and independent contractors can also receive a new form of unemployment assistance, Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) benefits, as a result of the federal CARES Act.

Some asked for completely suspending or waiving rent and utility payments, along with loan and interest payments. “[I need] rental relief due to no income at this time,” one respondent wrote. One respondent said they needed “rent abatement (not just delay or waiver of interest/penalties), payroll help, payroll tax abatement, [and] swift re-opening plans so I can give the employees something to look forward to. I do not want to lose these great employees that we have trained over the years.” Another respondent echoed this: “We need a rent freeze and we need our clients to have financial support through this recession.” “I think that commercial and residential loans should be frozen until the local and federal emergencies have ended,” another said.

Recent local legislation now ensures that commercial tenants cannot be evicted during the public health emergency, and landlords also cannot raise commercial rents or charge late fees for late rent payments during this time. The same protections apply for residential properties, and utility companies cannot shut off gas, water, or electric service for nonpayment; internet service likewise cannot be shut off, although it can be downgraded.

Several respondents also suggested ways to streamline processes and remove barriers that could prevent small businesses from accessing much-needed funds. “Eliminate credit score criteria as access to credit,” one wrote. Another requested “swift response to loan applications,” and for more small business grants that were less restrictive in their requirements. “Remove personal guarantees from loans,” requested another.

Permits were also a source of concern for many respondents. One said that they would be helped by “elimination of expedited permit review fees,” along with reducing regular permit fees and extending permit validity. Others also emphasized the importance of speedy permit review processes, or extended grace periods for renewals if that is not possible.

Some respondents had suggestions for how to increase business opportunities for small and local businesses in this new environment. One suggested the D.C. government “break and unbundle large contracts into smaller opportunities for more local small businesses.” Another in the food industry suggested that more be done to use small businesses to meet larger orders, such as catering and lunch orders for larger institutions.

Ben’s Chili Bowl and Next Door on March 19, 2020 (Source: Ted Eytan)

Uncertainty about the future

Among D.C. businesses, many who have already closed are unsure whether they would be able to survive long enough to make it to the end of the crisis. One respondent said, “We will have almost no revenue for the foreseeable future. We cannot pay bills or staff, and right now we are not even sure if we will be able to bounce back after all this.” Another wrote, “If I have no clients I have no money. The future is unknown and I am trying to be socially responsible and close—but have no idea for how long.”

One respondent said their major concern was “massive disruption to the demand side of the business. [I’m] fearful lenders will stop lending on all [manner] of existing loan products and will no longer lend on new deals. I am terrified.”

Many small businesses in D.C. are worried that the road to recovery will be long and challenging. One respondent to our questionnaire wrote that they were most concerned about “Being able to return, rehire our team and operate in what will likely be a fragile economy.” Another respondent said, “The uncertainly and panic is resulting in current and future project pipelines being decimated. Having no in-person business development opportunities makes it difficult to make up for lost business.”

Several noted that the loans they were taking out now to stay afloat could make it more difficult for them to get back up to speed when business started up again. One respondent said that one of their biggest risks was “reopening in massive debt due to taking out new loans, lines of credit, and being behind months in rent to [landlords]. Even if we start operating again, business will be slow for a considerable amount of time—we will be hurt even when we begin operations again. Our new normal will not be enough to overcome the debt needed to get through this and our economic viability could take years to return to normal.”

Many respondents were clear that re-opening would not mean they could immediately return to pre-pandemic business levels, especially for businesses that laid off most or all of their staff members. “Businesses will shed employees and once things turn around, it will be hard to get them back or find new ones, creating a large lag,” one respondent wrote.

Downtown D.C. on April 7, 2020. (Source: Ted Eytan)

Cascading impacts will ripple outward

Customer-facing industries have been most directly affected by city- and state-wide shutdowns in the current stage of the pandemic, and have likewise seen the most severe immediate impacts. But even small businesses that have been able to conduct their work remotely are feeling the impacts, which will likely become more severe as economic conditions worsen.

One respondent said their major concern was “Surviving financially. All of my clients are cancelling because of social distancing.”

Among small businesses in D.C. who have been able to shift to remote work, many are still concerned about the downstream effects of the crisis, especially those whose main clients are businesses that have been more directly affected by shutdowns and sudden drops in revenue. One respondent said, “During the 09/11 crisis, I lost almost all of my clients. I do… freelance writing and sometimes social media design. If small businesses fail, I fail, too. I am not sure what my backup plan is at this moment. I get a decent amount of work, but that could change. I am worried that my clients will fail.”

Some respondents said they were concerned that their clients did not have the capabilities to work remotely, even if they could otherwise continue operations. “We believe that our business fundamentals and clients are very strong, but their operations are being impacted by closures and their staff problems,” one respondent wrote. “Many of our clients did not have robust IT platforms to support work from home. [Some] clients don’t have extensive laptop distribution for their employees.”

14th St NW on March 22, 2020 (Source: Ted Eytan)

Local resilience and recovery tied to federal response, public health outcomes

In the immediate term, small businesses are seeking life support: Support to avoid laying off workers if they can, direct unemployment support to workers if they can’t; assistance with rent; and quick response from regulators and others in government to help them pivot to new opportunities where they can. Since many entrepreneurs and small businesses—especially Black-owned businesses—rely on personal resources instead of traditional loans or funding from investors, individual- and household-level supports from the federal and D.C. governments will also be vital resources.

The first waves of federal legislation have addressed many immediate impacts with sick leave, expanded unemployment insurance, and one-time financial supports. Locally, the D.C. Council and Mayor have also responded with several measures, and will continue to provide supports as they can. But because the District—like most states—must have a balanced budget, its ability to fully respond countercyclically to economic shocks on its own is limited. (In D.C., the stakes are particularly high, as large deficits could eventually trigger a return of a presidentially appointed control board.)

The D.C. CFO recently announced that the District is facing a $722 million shortfall in revenues for FY 2020, meaning that the District will need to make drastic cuts to its current fiscal year of spending, and that revenues for FY 2021 are now expected to be $774 million less than previously forecasted. These changes could be even more severe—or less: “There is a high degree of uncertainty around the forecast,” the CFO’s update says, “because the rapid spread of the virus and the measures to control it are without precedent in recent history.”

Ultimately, the duration and severity of the present economic hardships will depend on the local, national, and international response to the pandemic, and the timeline of D.C.’s economic recovery dependent on the success of public health measures. And while a few small business respondents had voiced skepticism, in late March, of the necessity of potential business closures, several also recognized that the crisis was driven by the need to contain the virus. Asked about how the D.C. government should support small businesses, for instance, one respondent wrote: “Getting everyone healthy as soon as possible so we can get back to normal (or close to it).”

The Mayor’s office recently shared a report from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security that provides state-level guidance for a phased reopening, and announced a ReOpen DC Advisory Group, whose work will be guided by that research—but the Mayor and leading D.C. government health officials has stressed that the city will not consider reopening until the number of new COVID-19 cases has fallen consistently for two weeks.

About the data

In mid-March, the D.C. Policy Center shared a questionnaire about how small businesses are responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. These questionnaires, distributed primarily through industry groups and other existing networks by email, were not meant to be representative surveys. Instead, they were an opportunity for small businesses to tell us, in their own words, their concerns about their future in an uncertain economic and public health environment. We received over 200 responses from small businesses based in D.C. and in the broader metropolitan area. By pairing these qualitative responses with national surveys and economic data, we hope to provide a useful look at how D.C. businesses are experiencing the COVID-19 crisis, and what they need to survive and recover in the months ahead.

Share your experiences

Going forward, we will continue to work closely with business leaders, community groups, foundations, partners in the D.C. government, members of the Council, and others deeply involved in the District’s response to this crisis. If you would like to learn more, or would like to collaborate in these efforts, please contact Yesim Sayin Taylor at yesim@dcpolicycenter.org or leave a voicemail at (202) 202-2233.

Feature photo by Ted Eytan (Source). Sunaina Kathpalia created the charts on small businesses distributions in D.C. for this analysis.

Kathryn Zickuhr is the Director of Policy at the D.C. Policy Center.